Abstract

This study aims to (1) examine the variation in implementation of a 2-year chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) management programme called RECODE, (2) analyse the facilitators and barriers to implementation and (3) investigate the influence of this variation on health outcomes. Implementation variation among the 20 primary-care teams was measured directly using a self-developed scale and indirectly through the level of care integration as measured with the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) and the Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC). Interviews were held to obtain detailed information regarding the facilitators and barriers to implementation. Multilevel models were used to investigate the association between variation in implementation and change in outcomes. The teams implemented, on average, eight of the 19 interventions, and the specific package of interventions varied widely. Important barriers and facilitators of implementation were (in)sufficient motivation of healthcare provider and patient, the high starting level of COPD care, the small size of the COPD population per team, the mild COPD population, practicalities of the information and communication technology (ICT) system, and hurdles in reimbursement. Level of implementation as measured with our own scale and the ACIC was not associated with health outcomes. A higher level of implementation measured with the PACIC was positively associated with improved self-management capabilities, but this association was not found for other outcomes. There was a wide variety in the implementation of RECODE, associated with barriers at individual, social, organisational and societal level. There was little association between extent of implementation and health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Integrated Disease Management (DM) is a popular approach for improving the quality and efficiency of care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients. However, the key elements of DM programmes for COPD (herein, COPD-DM) are not yet fully understood.1–3 The cost-effectiveness of these programmes varies considerably,4 most likely depending on the duration, target population and components of the intervention.5,6 Moreover, wide variation exists, even in the implementation of a single programme.7,8 This variation can be due to adjustments for the local setting, or due to differences in specific barriers and facilitators that influence implementation.9,10 Therefore, it is important to understand the conditions needed for the successful implementation of a DM programme.11

We aimed to (i) examine the variation in implementation of a single COPD-DM programme (RECODE) between different primary-care teams, (ii) analyse the facilitators of and barriers to implementation and (iii) investigate the association between the extent of implementation and health outcomes. This study was performed as a pre-specified part of the RECODE trial.12

Results

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the teams and their COPD patients. Each team enrolled 11–55 patients and 53 percent of the teams were delivering ad hoc reactive care.

The telephone interviews were held with five general practitioners (GPs) and 17 practice nurses from 17 of the 20 (85%) teams. These interviews varied in length between 20 and 45 min. Three (15%) teams could not be interviewed because the participating caregiver(s) had left or changed practice or because the caregiver(s) lacked time. The response rate of the questionnaires can be found in Appendix 2.

Implementation

The teams implemented, on average, 8 of the 19 interventions (range: 2–14, Table 2). The most frequently applied interventions were cooperation with physiotherapist(s) (88%), exacerbation management (76%) and active identification and monitoring of high-risk COPD patients (71%). Only a few teams improved cooperation with lung specialist(s) (18%), substituted care from secondary to primary care (24%), actively applied motivational interviewing to improve self-management (18%) and used additional funding for physiotherapy (12%). In the second study year, none of the teams used the ITC system 'Zorgdraad'. Teams with a lower starting level implemented, on average, more interventions than did teams with a higher starting level.

The total Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) score did not significantly change over the study period (Table 3). However, the PACIC component ‘decision support’ significantly decreased. Even though the total Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC) score did not significantly change, the ACIC components ‘organisation of healthcare system’, ‘community linkages’ and ‘self-management’ significantly improved over the first year.

Barriers and facilitators

Table 4 summarises the barriers and facilitators to implementation as they were perceived by the teams grouped into individual, social, organisational and broader societal factors. These groups were not mutually exclusive.

Individual factors

Caregivers were positive about the RECODE course, stating that it was informative, increased attention to COPD, and inspired and motivated them to improve COPD care. For instance, 13 teams reported a greater awareness of early recognition of exacerbations, and many teams implemented symptom-reporting policies to increase early treatment of exacerbations. Teams also fine-tuned self-management, which was already (partly) integrated. For instance, most teams were familiar with motivational interviewing and individual treatment plans, but not every plan was put in writing or was made in consultation with the patient.

A barrier to implementation was the lack of motivation of patients. Several teams reported difficulties in persuading COPD patients to adopt healthier behaviour because they did not feel ill or did not experience (many) problems. Furthermore, because of the lack of patients’ motivation, familiarity with computers and obligation to use web-based applications, few patients used Zorgdraad. The lack of motivation or time to determine how Zorgdraad worked was also an important barrier among caregivers in using Zorgdraad.

Social factors

During the refresher courses, the teams discussed their implementation experiences with other teams. That way they motivated, inspired and learnt from each other. These presentations were generally appreciated, although some were dissatisfied that presenters had begun implementation rather late, as a result of which they had little experience to share.

The professional network in which the teams operated was also a barrier to implementation. For instance, inconsistent use of Zorgdraad among team members jeopardised the potential contribution of Zorgdraad to their purposes.

Organisational factors

Teams with a lower starting level had more room for improvements. For example, only teams with no structured COPD care developed new protocols. Furthermore, four teams changed smoking cessation support because most teams reported that this was already integrated in their COPD care. Moreover, four teams did not re-allocate tasks from the GP to the practice nurse because they reported that most of the COPD care had already been re-allocated to the practice nurse.

The implementation was also facilitated by the feedback reports on the health outcomes of their patients that each practice received. Several teams indicated a better overview and greater ability to manage progression of their COPD patients. In this way, the reports helped to actively track high-risk COPD patients.

Four teams reported changes in referring patients to primary/secondary care. Three teams explicitly discussed referral criteria, whereas in one team the lung specialist noticed changes in primary care and referred more patients back without explicit deliberation. A barrier for task re-allocation from secondary to primary care was that not every lung specialist adhered to the new agreements.

The main barrier to improving cooperation with the dietitian was the low proportion of patients who were eligible to be referred for nutritional support. The low number of patients and staff turnover was also reported as reasons for not using Zorgdraad and organising periodically scheduled multidisciplinary meetings. In addition, problems with transferring information to the team’s information system was an important barrier in Zorgdraad.

Broader societal factors

A bundled payment scheme for COPD patients was introduced in the Netherlands, almost simultaneously with the start of RECODE.13 Since this reform, health insurers purchase integrated multidisciplinary COPD care from care groups. As a result, the focus on COPD care increased, financial coverage improved, and/or secondary caregivers became more involved. This facilitated the implementation of RECODE. However, three teams reported that they abandoned or temporarily stopped RECODE because they had to concentrate on preparing the integrated care programme as was purchased by the insurer and the formal installation of a care group. A care group is a legal entity, usually owned by GPs, which subcontracts individual professionals to provide care.

The lack of full reimbursement of physiotherapy and smoking cessation support was an important barrier to patient participation in these RECODE components. The lack of reimbursement of physiotherapy was partly solved by the RECODE research team, which arranged supplementary funding by healthcare insurers for COPD-specific exercise training programmes for patients with an MRC (Medical Research Council) dyspnoea score >2, including those without supplementary health insurance. The reason for the limited use (12%) of the funding remains unclear. One respondent stated that the funding was not used because attention to RECODE declined, and many patients did not qualify for the reimbursement.

Association between level of implementation and health outcomes

Table 5 shows the association between the level of implementation of RECODE (as measured either by our own implementation scale, by the change in PACIC or the change in ACIC) and the change in health outcomes within the same time period. A higher level of integrated care as measured by the self-developed scale was not associated with better health outcomes (Table 5). The indirect assessment of implementation, measured as the change in the level of integrated care from the patient’s perspective (PACIC), was associated with a significantly higher ‘SMAS (Self-Management Ability Scale), taking initiatives’ score and a significantly higher ‘SMAS, investment behaviour’ score. For example, one unit improvement in PACIC score between baseline and 24 months was associated with a 1.2 unit improvement in ‘SMAS taking initiative score’ between baseline and 24 months. This association was not found in other health outcomes. Over the 1-year study period, the total score on changed level of integrated care from the healthcare provider’s perspective (ACIC) was not associated with better health outcomes. Within the subgroup of patients with a clinically relevant improvement on the CCQ (Clinical COPD Questionnaire) or SGRQ (St George Respiratory Questionnaire), a higher level of integrated care (self-developed scale, PACIC or ACIC) was not associated with better health outcomes.

Discussion

Main findings

This study showed that a pragmatic (non-experimental) implementation of a COPD-DM programme resulted in a low level and a wide variety of implementation across different teams. Important barriers to implementation were insufficient motivation of patients, high starting level of COPD care, small size of the COPD population per team, mild COPD population, practicalities of the ICT system, and hurdles in the reimbursement. Level of implementation as measured with our own scale and the ACIC was not associated with health outcomes. A higher level of implementation measured with the PACIC was positively associated with improved self-management capabilities, but this association was not found for other outcomes.

Interpretation of findings in relation to previously published work

In line with previous pragmatic studies,14,15 the teams implemented various interventions, but none implemented all interventions. Indeed, on average, less than half (42%) of the interventions were implemented despite the fact that the individual interventions have been shown to improve health outcomes.1,5,16,17 These findings further support the idea of Pinnock et al18 who suggest that after proven efficacy the translation of interventions into a practical service should be evaluated in an implementation study. This translation seems to result in lower but more realistic outcomes of the interventions.19,20

RECODE was facilitated by informed and motivated caregivers, which corroborates an earlier study.10 Despite this, the caregivers were not able to implement all the interventions. In addition, they became demotivated because Zorgdraad was not adequately functioning on time.

COPD patients were not always motivated to change; as COPD patients perceive their suboptimal health status as ‘normal’, COPD had become a way of life.21 Excluding unmotivated patients may improve the (cost-)effectiveness of COPD-DM programmes. Specific interventions to change the motivational status of patients are therefore required.

A barrier for implementation was the low potential for improvement owing to the high starting level of COPD care and the mild COPD population. The absence of improvements owing to already high levels of COPD care was pointed out in earlier primary-care trials.22,23

The perceived usefulness of Zorgdraad was low. The teams that did use Zorgdraad experienced problems with practicalities and variability in adoption of the system between team members. Furthermore, teams reported unclear instructions and a lack of time or motivation to determine how Zorgdraad worked. A large review corroborates that usefulness, compatibility with work and time were important barriers for the implementation of an ICT system.24

The last important barrier to implementation was the hurdle in reimbursement. As teams reported the formation of care groups as facilitators, the ongoing wide implementation of the bundled payment system in the Netherlands might be a positive step towards solving the reimbursement issue. In this system, healthcare insurers purchase integrated multidisciplinary COPD care from care groups.25 However, in practice, the financed package varies widely, and therefore not all multidisciplinary care required by a COPD patient is included.26

In accordance with our results, previous studies have demonstrated that an improved PACIC score improved self-management.14,27 Despite this, our self-developed scale or ACIC score was not associated with better health outcomes. Therefore, implementation of only a few interventions by some teams does not guarantee improvements in patient outcomes in comparison with other teams.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study has several strengths. First, a broad range of outcome measures and implementation measurements including different perspectives were used. Second, independent scoring of the self-developed scale ensured the objectivity of the results. Third, the interviewer was not involved in the core research team, which reduced the pressure to give desirable answers.

This study also has several weaknesses. It was not possible to compare the implemented interventions of the intervention teams with the control teams because, to prevent an additional intervention effect, we did not evaluate changes in COPD care in the control group. Therefore, it was not always possible to determine whether changes were caused by RECODE or other factors, such as parallel projects. Second, most interviews were held with only one representative of the team. However, we interviewed practice nurses or GPs, who were the project leaders and provided the best overview of COPD care in their team. Third, the response rate on the ACIC questionnaire at 12 months was low (65%). However, the ACIC score at baseline did not differ much between the responders and the non-responders.

Implications for future research, policy and practice

This study showed that a pragmatic COPD-DM programme that primarily targets caregivers seems to result in only modest improvements in care. We learnt that focus should be more on patient-oriented interventions. Hence, multiple COPD-DM programmes have shown that patient-oriented interventions or a combination of patient-oriented, provider-oriented and organisational interventions lead to significant improvements in health outcomes.14,28 Furthermore, the interventions should be tailored to patients’ needs, skills and preferences, which will imply that, on average, a COPD-DM programme for milder COPD patients will include fewer or less-intensive interventions than a COPD-DM programme for more severe patients.

The room for improvement and the proportion of motivated patients is higher among a selection of COPD patients with a high disease burden. However, focussing on more severe COPD reduces the number of patients who participate in the programme. Consequently, the motivation of professionals to invest time in optimising the programme and negotiating with health insurers on reimbursement of the programme may decrease. It is a challenge for further programmes to find the right balance between sufficient room for improvement and economies of scale. In finding this balance, we should account for the fact that long-term gains can be increased if we can prevent moderate COPD patients from progressing to severe COPD.

Conclusions

This study adds valuable input to the discussion on development and implementation of COPD-DM programmes. We observed a low level and wide variability of implementation across different primary-care teams. Barriers and facilitators of the implementation were related to factors at individual, social, organisational and broader societal level. There was little association between the level of implementation and improved health outcomes.

Materials and methods

Intervention

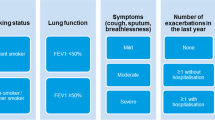

RECODE is a two-year cluster-RCT in which 40 primary-care teams were randomised to DM or usual care.12 The 20 intervention teams received a 2-day training course in essential elements of effective COPD-DM. These elements are grouped by components of the Chronic Care Model (CCM), and described in Figure 1. The CCM is often used as conceptual framework for development and evaluation of DM programmes.1,5,16,29 The core of the CCM is the productive interaction between informed, activated patients and prepared, proactive teams of caregivers.30 RECODE included interventions to improve five of the six interrelated CCM components. After the course, the teams were invited to join two refresher courses and had access to the ICT system ‘Zorgdraad’. All the teams were encouraged to write their own reform plan and tailor implementation strategies to their local circumstances. Therefore, the package of interventions that patients received was not only dependent upon their health status, personal needs and preferences but also on local adaptation and level of implementation of interventions.

The RECODE interventions grouped by the components of the Chronic Care Model (CCM) from Wagner et al.30 COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GP, general practitioner; ICT, information and communication technology.

The ICT system ‘Zorgdraad’ included a patient portal and a healthcare provider portal, but was not an e-consultation system. The patient portal contained educational material and had a section containing personal treatment goals and room to write down personal notes. The provider portal had room for a protocol to guide frequency and content of COPD monitoring, entering quality-of-life scores and results from follow-up and examinations. Information from Zorgdraad was used to generate practice-tailored feedback reports on patients’ health outcomes at baseline and at 6 and 12 months. These reports were generated by the researchers and sent to the practices to support prioritising the healthcare needs. It was intended that practice nurses would give the COPD patients instructions and information through the patient portal.

Participants

The 20 intervention teams included at least one GP, one practice nurse and one physiotherapist specialised in COPD care. Thirteen teams also included a dietitian. The teams enrolled 554 COPD patients according to the Global Initiative for COPD (GOLD) guidelines,31 and because few exclusion criteria were applied, they represent the primary-care COPD population in the Netherlands.12

Setting

In the Netherlands, GPs act as gatekeepers to hospital care; patients need a referral from the GP to visit a specialist in a hospital clinic.32 Hence, the vast majority of COPD patients are treated by the GP. The Ministry of Health activity has been stimulating the implementation of integrated care programmes for chronic diseases such as COPD for quite some time. This was reinforced by the introduction of a bundled payment system in 2010.13 This has strengthened the collaboration between different primary-care professionals involved in COPD care. Primary-care practice nurses have a key role in providing integrated care. A practice nurse is a new profession that was introduced in the early 2000s, and several tasks formerly performed by GPs were shifted towards this nurse.32 The majority (80%) of the practice nurses have a general background in nursing and receive additional training in one or more chronic diseases. They are predominantly involved in the care of chronically ill patients. For COPD patients this includes, for example, periodic monitoring, spirometry testing, inhalation instructions, smoking cessation counselling, coaching patients to become more physically active, and teaching patients to recognise exacerbations early.33 At present, 80% of the Dutch practices, which have an average practice size of 2,350 patients, have at least one practice nurse who takes care of chronically ill patients for at least 2 days a week.

Implementation

The level of implementation was measured directly with a self-developed scale. The scale measured the implementation of 19 interventions in five CCM components that were included in the RECODE programme (Appendix 1). Three researchers independently assessed whether an intervention was actually implemented (score=1) or not (score=0), and disagreements were discussed in a consensus meeting. The sum of these 19 scores comprised the total score on the self-developed scale. The information that the researchers used to score the scale was obtained from a questionnaire administered to the teams after 1 year and a semi-structured telephone interview with the teams after 2 years. Questions were asked about COPD care before RECODE, changes in COPD care as a result of RECODE, and barriers to and facilitators of implementation. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Finally, information was recorded on attendance of professionals at the training and refresher courses, as well as on ICT use and use of additional reimbursement for physiotherapy.

The level of implementation was also measured indirectly through the assessment of the level of integrated care that was achieved. The latter was measured from the patient’s perspective with the PACIC Questionnaire34 at baseline and at 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months (ranging from 1 (lowest level) to 5 (highest level)) and from the healthcare provider’s perspective using the ACIC (ranging from 0 to 11, with 11 representing optimal care) at baseline and at 12 months.35

Barriers and facilitators

Reported barriers and facilitators of implementation were categorised as individual, social, organisational or broader societal factors.36 Individual factors were related to caregivers and consisted of cognitive, motivational and behavioural factors, as well as personal characteristics including health status. Social factors were related to professional teams/networks. Organisational factors included the organisational structure, culture and work processes, as well as the availability of necessary resources. Societal factors related to the healthcare system and to societal and political developments.

Starting level

We distinguished three starting levels: (i) ad hoc reactive COPD care; (ii) structural diagnosis of COPD patients; and (iii) structural diagnosis and proactive follow-up of COPD patients. Teams with ‘ad hoc reactive COPD care’ had (virtually) no DM. For these teams, RECODE marked the start of structured COPD care. Teams with ‘structural diagnosis of COPD patients’ had begun to structure their COPD care, performed spirometry and had an overview of the COPD population in their practice. Teams with ‘structural diagnosis and proactive follow-up of COPD patients’ additionally had an established control-visit/follow-up structure, and applied strategies to support self-management.

Health outcomes

We measured health-related quality of life on the CCQ,37 SGRQ38 and the EQ-5D.39,40 We measured dyspnoea by means of the MRC dyspnoea score with a scale from 1 to 5,41 physical activity by means of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire42 and self-management abilities by means of the components ‘taking initiatives’, ‘investment behaviour’ and ‘level of self-efficacy’ from the Self-Management Ability Scale-30.43 The questionnaires were administered at baseline and at 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of patients’ and teams’ characteristics were calculated. We used two-tailed, paired t-tests to investigate improvements in the level of integrated care as measured by the PACIC and the ACIC.

During the RECODE study, there was a variation in changed outcomes in the intervention group.44 In this study, we investigated the association between variation in implementation as measured with our own developed scale and ACIC and change in health outcomes within the same time period using two-level (patients nested in teams) linear mixed-effect models, correcting for starting score of different health outcomes and starting level of COPD care. To investigate the impact of the level of implementation as measured with the PACIC on change in health outcomes within the same time period, we used three-level (longitudinal measurements nested in patients nested in primary-care teams) linear mixed-effect models, correcting for time, starting score of different health outcomes and starting level of COPD care. We used six time points (baseline, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months) to estimate the impact of implementation as measured with the PACIC. These models were specified for eight dependent variables: change in CCQ, SGRQ, EQ-5D, MRC, MET minutes, taking initiatives, investment behaviour and self-efficacy.

References

Steuten, L. M., Lemmens, K. M., Nieboer, A. P. & Vrijhoef, H. J. Identifying potentially cost effective chronic care programs for people with COPD. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 4, 87–100 (2009).

Peytremann-Bridevaux, I., Staeger, P., Bridevaux, P. O., Ghali, W. A. & Burnand, B. Effectiveness of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-management programs: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 121, 433, 443.e4 (2008).

Ouwens, M., Wollersheim, H., Hermens, R., Hulscher, M. & Grol, R. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: a review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 17, 141–146 (2005).

Tsiachristas, A., Cramm, J. M., Nieboer, A. P. & Rutten-van Molken, M. P. Changes in costs and effects after the implementation of disease management programs in the Netherlands: variability and determinants. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 12, 17, 7547-12-17. eCollection 2014 (2014).

Boland, M. R., Tsiachristas, A., Kruis, A. L., Chavannes, N. H. & Rutten-van Molken, M. P. The health economic impact of disease management programs for COPD: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 13, 40 (2013).

Kruis, A. L. et al. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10, CD009437 (2013).

Gottlieb, V., Lyngso, A. M., Nybo, B., Frolich, A. & Backer, V. Pulmonary rehabilitation for moderate COPD (GOLD 2)--does it have an effect? COPD 8, 380–386 (2011).

Bucknall, C. E. et al. Glasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 344, e1060 (2012).

Walters, B. H., Adams, S. A., Nieboer, A. P. & Bal, R. Disease management projects and the Chronic Care Model in action: baseline qualitative research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 12, 114, 6963-12-114 (2012).

Grol, M. J. P. & Wensing, in Implementatie; effectieve verbetering van de patiëntenzorg 4th edn (Elsevier: Maarssen, 2011).

Hulscher, M. E., Laurant, M. G. & Grol, R. P. Process evaluation on quality improvement interventions. Qual. Saf. Health Care 12, 40–46 2003).

Kruis, A. L. et al. RECODE: Design and baseline results of a cluster randomized trial on cost-effectiveness of integrated COPD management in primary care. BMC Pulm. Med. 13, 17 (2013).

Tsiachristas, A. et al. Towards integrated care for chronic conditions: Dutch policy developments to overcome the (financial) barriers. Health Policy 101, 122–132 (2011).

Bodenheimer, T., Wagner, E. H. & Grumbach, K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA 288, 1909–1914 (2002).

Pearson, M. L. et al. Assessing the implementation of the chronic care model in quality improvement collaboratives. Health Serv. Res. 40, 978–996 (2005).

Adams, S. G. et al. Systematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and management. Arch. Intern. Med 167, 551–561 (2007).

Lemmens, K. M., Nieboer, A. P. & Huijsman, R. A systematic review of integrated use of disease-management interventions in asthma and COPD. Respir. Med. 103, 670–691 (2009).

Pinnock, H., Epiphaniou, E. & Taylor, S. J. Phase IV implementation studies. The forgotten finale to the complex intervention methodology framework. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 11 (Suppl 2): S118–S122 (2014).

Pinnock, H. et al. Accessibility, acceptability, and effectiveness in primary care of routine telephone review of asthma: pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 326, 477–479 (2003).

Pinnock, H. et al. Accessibility, clinical effectiveness, and practice costs of providing a telephone option for routine asthma reviews: phase IV controlled implementation study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 57, 714–722 (2007).

Giacomini, M., DeJean, D., Simeonov, D. & Smith, A. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 12, 1–47 (2012).

Bischoff, E. W. et al. Comprehensive self management and routine monitoring in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in general practice: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 345, e7642 (2012).

Pinnock, H. et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 347, f6070 (2013).

Gagnon, M. P. et al. Systematic review of factors influencing the adoption of information and communication technologies by healthcare professionals. J. Med. Syst. 36, 241–277 (2012).

Tsiachristas, A., Dikkers, C., Boland, M. R. & Rutten-van Molken, M. P. Exploring payment schemes used to promote integrated chronic care in Europe. Health Policy 113, 296–304 (2013).

Evaluatiecommissie Integrale Bekostiging. Monitoring Integrale Bekostiging Zorg voor Chronisch Zieken. Tweede rapportage van de Evaluatiecommissie Integrale Bekostiging, 2 (2012).

Schmittdiel, J. et al. Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) and improved patient-centered outcomes for chronic conditions. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 23, 77–80 (2008).

Lemmens, K. M. et al. Bottom-up implementation of disease-management programmes: results of a multisite comparison. BMJ Qual. Saf. 20, 76–86 (2011).

De Bruin, S. R., Heijink, R., Lemmens, L. C., Struijs, J. N. & Baan, C. A. Impact of disease management programs on healthcare expenditures for patients with diabetes, depression, heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review of the literature. Health Policy 101, 105–121 (2011).

Wagner, E. H. et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Improv. 27, 63–80 (2001).

Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) (2014); http://www.goldcopdorg/2014.

Schafer, W. et al. The Netherlands: health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 12, v–xxvii, 1–228 (2010).

Heiligers, P. J. M. et al. Praktijkondersteuners in de huisartsenpraktijk (POH's), klaar voor de toekomst? [Knowledge Base: Practice Nurses in the GP Practices, Ready for the Future?]. NIVEL: Utrecht, The Netherlands, (2012).

Glasgow, R. E. et al. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med. Care 43, 436–444 (2005).

Bonomi, A. E., Wagner, E. H., Glasgow, R. E. & VonKorff, M. Assessment of chronic illness care (ACIC): a practical tool to measure quality improvement. Health Serv. Res. 37, 791–820 (2002).

Grol, R., Wensing, M., Eccles, M. & Davis, D . Improving Patient Care: The Implementation of Change in Health Care (Jown Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013).

van der Molen, T. et al. Development, validity and responsiveness of the Clinical COPD Questionnaire. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 1, 13 (2003).

Jones, P. W., Quirk, F. H., Baveystock, C. M. & Littlejohns, P. A self-complete measure of health status for chronic airflow limitation. The St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 145, 1321–1327v (1992).

Brazier, J., Roberts, J., Tsuchiya, A. & Busschbach, J. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Econ. 13, 873–884 (2004).

Lamers, L. M., McDonnell, J., Stalmeier, P. F., Krabbe, P. F. & Busschbach, J. J. The Dutch tariff: results and arguments for an effective design for national EQ-5D valuation studies. Health Econ. 15, 1121–1132 (2006).

Bestall, J. C. et al. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 54, 581–586 (1999).

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ); Scoring protocol (2005). Available at http://www.ipaq.ki.se/scoring.htm(accessed 5, 2013).

Schuurmans, H. et al. How to measure self-management abilities in older people by self-report. The development of the SMAS-30. Qual. Life Res. 14, 2215–2228 (2005).

Kruis, A. L. et al. Effectiveness of integrated disease management for primary care chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: results of cluster randomised trial. BMJ 349, g5392 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Stichting Achmea, a Dutch Healthcare Insurance Company, and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Zon-MW), subprogramme Effects and Costs (project number 171002203). The funding agencies (Achmea Zorgverzekeringen and Zon-MW) have no influence on the analysis and writing of the papers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB was involved in the study design, data collection, statistical analysis and writing of the manuscript. MB, AK and SH independently scored the implementation scale. In addition, AK was involved in the data collection and writing of the manuscript. SH interviewed the healthcare professionals and participated in writing of the manuscript. AT and MR contributed to the study design, data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. WJ, JG, CB and NC participated in the data collection, interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Boland, M., Kruis, A., Huygens, S. et al. Exploring the variation in implementation of a COPD disease management programme and its impact on health outcomes: a post hoc analysis of the RECODE cluster randomised trial. npj Prim Care Resp Med 25, 15071 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.71

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.71

This article is cited by

-

Characteristics of self-management education and support programmes for people with chronic diseases delivered by primary care teams: a rapid review

BMC Primary Care (2024)

-

Patient Assessment Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) and its associations with quality of life among Swiss patients with systemic sclerosis: a mixed methods study

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2023)

-

Evolutionary game model of health care and social care collaborative services for the elderly population in China

BMC Geriatrics (2022)

-

Exploring characteristics of COPD patients with clinical improvement after integrated disease management or usual care: post-hoc analysis of the RECODE study

BMC Pulmonary Medicine (2020)

-

The impact of integrated disease management in high-risk COPD patients in primary care

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2019)