Abstract

One of the important factors limiting solar-cell efficiency is that incident photons generate one electron–hole pair, irrespective of the photon energy. Any excess photon energy is lost as heat. The possible generation of multiple charge carriers per photon (carrier multiplication) is therefore of great interest for future solar cells1. Carrier multiplication is known to occur in bulk semiconductors, but has been thought to be enhanced significantly in nanocrystalline materials such as quantum dots, owing to their discrete energy levels and enhanced Coulomb interactions1,2,3. Contrary to this expectation, we demonstrate here that, for a given photon energy, carrier multiplication occurs more efficiently in bulk PbS and PbSe than in quantum dots of the same materials. Measured carrier-multiplication efficiencies in bulk materials are reproduced quantitatively using tight-binding calculations, which indicate that the reduced carrier-multiplication efficiency in quantum dots can be ascribed to the reduced density of states in these structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Carrier multiplication is the process in which the absorption of a single, high-energy photon results in the generation of two or more electron–hole pairs. The excess energy of the initially excited electron is used to excite a second electron over the bandgap, rather than being converted into heat through sequential phonon emission. Carrier multiplication is important for the operation for high-speed electronic devices4, but is especially relevant for solar cells1, because relaxation of hot carriers through phonon emission is a common loss mechanism in bulk semiconductor solar cells. In this context, semiconductor quantum dots are promising building blocks for future solar cells1. In addition to the size-tunability of the quantum-dot optical properties, the carrier-multiplication efficiency in quantum dots was reported to be much higher than in bulk materials, where the process is generally referred to as impact ionization. It has been argued that carrier multiplication is more efficient in nanostructured semiconductors owing to quantum-confinement effects causing (1) a slowing of the phonon-mediated relaxation channel1 and (2) enhanced Coulomb interactions2, resulting from forced overlap between wavefunctions and reduced dielectric screening at the quantum-dot surface3. In recent years, several femtosecond spectroscopy studies have revealed highly efficient carrier multiplication in PbSe and PbS (refs 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9), PbTe (ref. 10), CdSe (ref. 11), Si (ref. 12) and InAs (refs 13, 14) quantum dots.

Nearly concurrently, however, a controversy has emerged following reports of appreciably less efficient carrier multiplication in CdSe (ref. 15), InAs (refs 16, 17), PbS (ref. 18) and PbSe (refs 18, 19) quantum dots. In initial studies, carrier-multiplicationefficiencies may have been overestimated owing to several experimental complications, including too high excitation fluences (generating multiple carriers by sequential absorption of multiple photons), lack of stirring of quantum-dot suspensions (causing photo-induced charging) and sample-to-sample variability19. Furthermore, recent tight-binding calculations20 suggest carrier multiplication in quantum dots is not only not enhanced relative to bulk, but is actually lower. Answering the key question in the controversy—whether carrier multiplication is enhanced by quantum-confinement effects—requires a reliable comparison between carrier-multiplication efficiencies in bulk and quantum dots. Remarkably, reliable numbers for carrier-multiplication efficiencies in bulk materials are limited. PbSe and PbS are arguably the most important materials in the carrier-multiplication discussion, as their small bulk bandgap values result in an optimal energy gap for quantum dots of these materials to use the excess energy of visible photons. However, reports of bulk carrier-multiplication efficiencies in PbSe and PbS are, respectively, absent or dated21. For bulk PbS, carrier-multiplication efficiencies have been inferred in the 1950s from device photocurrent measurements, which require charges to move over large distances. As a result, recombination losses such as Auger recombination and trapping at surface defects can introduce uncertainties in the assessment of inherent carrier-multiplication quantum efficiencies in devices. In contrast, for quantum dots, carrier multiplication is studied with (optical) spectroscopic techniques that operate on ultrafast (sub-)picosecond timescales. Hence, a direct comparison between carrier multiplication in bulk and quantum dots requires assessment of bulk carrier-multiplication efficiencies on a similar, ultrafast, timescale (see Supplementary Information). Whereas time-resolved optical and infrared spectroscopies are ideally suited to probe carrier populations in colloidal quantum dots2,5,7,8,10,11,14,15,17,18,19,22,23,24, light of terahertz frequencies interacts strongly with free carriers and allows for the direct characterization of carrier density and mobility25,26,27. Here, we quantify carrier multiplication in bulk PbSe and PbS on ultrafast timescales using terahertz time-domain spectroscopy26 (THz-TDS). We directly determine the number of photogenerated electron–hole pairs per absorbed photon, η, for various photon energies from the ultraviolet to the infrared, picoseconds after photo excitation, allowing for a direct comparison with quantum-dot results. Our results show that, for a given photon energy, more electron–hole pairs per photon are generated in bulk than in quantum dots.

The reliable determination of carrier-multiplication efficiencies in single-crystalline ∼1 μm films of PbSe and PbS (see Supplementary Information for sample details) requires the accurate determination of two parameters: the number of absorbed photons per unit area and the number of generated carriers. We achieve a homogeneous photon flux using a diffuser and determine the fluence at the sample position with ∼3% accuracy using five calibrated pinholes with increasing area. For the calculation of the number of absorbed photons per square millimetre, the reflective losses at the sample surface have been taken into account (see Supplementary Information).

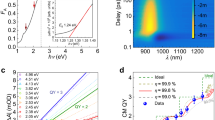

Second, the amount of generated electron–hole pairs is determined using THz-TDS measurements26. This technique has been used extensively to determine carrier dynamics in semiconductors, as it provides the frequency-dependent complex conductivity σ(ω) of charge carriers 25,27. We measure in the time domain the electric field of picosecond terahertz pulses transmitted through the unexcited sample E(t). The changes therein, ΔE(t), following photo injection of charge carriers using femtosecond laser pulses directly reflect the charge carrier density. Figure 1a shows the complex conductivity σ(ω) for PbS (Egap=0.42 eV) following excitation at 266 nm (4.66 eV), as inferred from the Fourier transforms of the time-domain fields27. We follow previous authors 26,27 and fit the data in Fig. 1a with the Drude model of free carriers, σ(ω)=(ɛ0ωp2τr)/(1−ω τr), where ωp is the plasma frequency, ɛ0 is the vacuum permittivity and τr is the carrier scattering time27. The plasma frequency is defined as ωp2=(e2N)/(ɛ0m*), where m* is the carrier effective mass and N is the carrier density. Combining the carrier density obtained from the Drude model with the number of absorbed 266-nm photons, we find that an average of 3.05±0.15 electron–hole pairs are generated by a photon with 11 times the energy of the bandgap (see the Methods section for detailed calculation), clearly demonstrating carrier multiplication. The same analysis for 800 nm excitation results in an average of 1.02±0.05 generated electron–hole pairs for each absorbed photon, indicating that carrier multiplication does not occur significantly for 800 nm excitation (3.7 times the bandgap energy).

a, Complex, frequency-dependent conductivity measured 10 ps after excitation with 266 nm light. The data (filled circles) are described well by the Drude response of free carriers (blue solid line), yielding the plasma frequency (directly related to density) and the carrier scattering time. b, ΔE(t) as a function of pump–probe delay for various 800-nm fluences. The increase of ΔE(t) with fluence is directly related to the higher carrier density, as explained in the text.

For all excitation wavelengths and excitation fluences used here, we verified that the changes in E(t) occur only through a change in carrier density (and not scattering time, see Supplementary Information). Hence, the magnitude of ΔE(t) is directly related to the number of photogenerated carriers and one can readily assess the excitation-wavelength-dependent carrier yield. Figure 2a shows ΔE(t) for PbS as a function of fluence for various photon energies. As ΔE(t) is proportional to the number of carriers, the slopes of the lines in Fig. 2a directly represent the number of carriers generated per absorbed photon, that is, the carrier-multiplication efficiency η. After normalizing to the 800 nm slope, for which we have verified that η=1, one finds η for the different photon energies. Figure 2b shows η versus photon energy for PbS, as inferred from our terahertz measurements, together with the reported values for a PbS photovoltaic cell21. The number of extra carriers created by carrier multiplication is over 1.5 times larger than concluded in ref. 21. As explained in the Supplementary Information, the carrier-multiplication efficiency in ref. 21 was underestimated, presumably because of oxidation of the PbS surface and/or trapping of carriers in defects. The values of η for bulk PbS and PbSe along with literature quantum-dot values are given in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. As experimental circumstances in early quantum-dot studies have resulted in overestimation of carrier-multiplication efficiencies19, we include only relatively recent reports in the comparison. Figure 3 demonstrates that carrier-multiplication efficiencies in bulk are higher than the quantum-dot values of refs 8, 9, 18 and 19, which were measured after the community had become aware of the complications of the determination of carrier multiplication in quantum dots. This observation indicates that quantum-confinement effects do not result in enhancement of carrier multiplication. In fact, carrier multiplication is significantly more efficient in bulk than in quantum-dot suspensions stirred to prevent photocharging 18,19. In the Supplementary Information, the format and interpretation of Fig. 3 is discussed in more detail.

a, Terahertz modulation as a function of absorbed photons per unit area for various photon energies for bulk PbS. The slopes of the lines are proportional to the electron–hole pair yield per absorbed photon. b, Average electron–hole pair generated per photon for varying photon energies, inferred from a, compared with a PbS photovoltaic cell21. The error bars indicate 95% confidence levels.

a,b, Values of η for quantum dots reported in the literature (markers of different colours) compared with bulk results from this work (black dots) for PbS (a) and PbSe (b). Most values of η for quantum dots lie at or below the bulk efficiency. Tight-binding calculations based on impact ionization for a range of phonon-assisted relaxation times (τph, black lines) yield carrier-multiplication efficiencies that are in good agreement with our experimental results. Coloured solid lines represent tight-binding calculations for PbSe quantum dots with a 0.6 and 1.2 eV energy gap, for τph=0.5 ps. The error bars indicate 95% confidence levels.

To gain insight into the mechanism of carrier multiplication in bulk and quantum dots, we have carried out tight-binding calculations (black lines for bulk and coloured lines for quantum dots in Fig. 3). We calculate, analogous to refs 20, 28 and 29, the matrix elements associated with transitions that lead to impact ionization, the process by which nascent photogenerated electrons (holes) relax towards the bottom (top) of the conduction (valence) band by generation of a second electron–hole pair, thus giving rise to carrier multiplication. After calculating the electronic structure of bulk PbSe and PbS in tight binding, we compute the matrix elements of the screened Coulomb interaction between two-particle states derived from tight-binding orbitals, as described in ref. 21. The impact ionization rates are obtained using the Fermi golden rule and are used as inputs in the numerical simulation of hot-carrier relaxation and carrier multiplication. In the calculation, impact ionization occurs in competition with phonon cooling, the relaxation of hot carriers by the emission of optical phonons characterized by the timescale τph, so that τph is a critical parameter in the calculations (see discussion in ref. 20). It is evident from Fig. 3 that the calculations describe the bulk data accurately for reasonable values of τph. Previously20, we have shown that impact ionization can also explain carrier multiplication in PbSe quantum dots. Combining our new experimental and theoretical efforts with the findings of ref. 20, we can quantitatively account for carrier multiplication in both bulk and quantum dots with impact ionization, without invoking mechanisms such as the coherent superposition of single- and multi-exciton wavefunctions4 or the occurrence of virtual single-exciton states5. Furthermore, it is evident that carrier multiplication is more efficient in bulk than in quantum dots. The conclusion that quantum-confinement does not lead to carrier-multiplication enhancement can be understood in the light of the present knowledge of three key aspects of dynamic processes and carrier–carrier interactions in bulk and quantum dots.

First, it has been proposed that the enhanced Coulomb interaction in quantum dots would lead to higher impact-ionization rates 2,19. However, the impact-ionization rate depends on both Coulomb interaction and the density of final (or bi-exciton) states 18,20. In quantum dots, the density of final states in quantum dots is reduced because of a discretization of the states. As a result, calculated impact-ionization rates are smaller in PbSe quantum dots than in bulk20. Apparently, the increase of Coulomb interactions in quantum dots is more than neutralized by the lower density of states. This theoretical prediction is confirmed experimentally in Fig. 3, where the quantum-dot data from refs 8, 9, 18 and 19 lie clearly below the bulk values.

Second, the process of carrier multiplication must compete with phonon-mediated intraband relaxation. Although such a relaxation mechanism was predicted to be slower in quantum-confined quantum dots than in bulk1, sub-picosecond relaxation can still occur by the transfer of excess energy to ligand vibrations or through an Auger process22,23. Recently, it has been demonstrated that these alternative relaxation pathways can be slowed down considerably, potentially making carrier multiplication much more favourable, for electrons in the 1P level by carefully engineering the quantum dots24. However, the excess energy of 1P electrons is typically insufficient to excite an extra electron over the bandgap. As the density of states in quantum dots increases rapidly for higher-lying energy levels, the intraband relaxation from these levels is expected to be fast because of the availability of phonon-mediated relaxation channels. Hence, fast phonon relaxation will always compete effectively with carrier multiplication in quantum dots.

Finally, the presence of large amounts of surface defects in quantum dots might provide an extra competing relaxation channel for hot carriers, possibly reducing the carrier-multiplication efficiency with respect to bulk. Differences in surface quality may also explain the sample-to-sample variability in carrier-multiplication efficiencies19 as observed in Fig. 3, even for quantum dots of the same energy gap. We note that, despite the scatter in quantum-dot data points, these lie below the bulk values.

The above argumentation on how phonon relaxation, Coulomb interaction and surface defects in quantum dots influence the carrier-multiplication efficiency is not strictly limited to PbSe and PbS quantum dots. Intraband relaxation is also known to proceed on ultrafast timescales in other quantum-dot materials 22,23. In addition, we carried out calculations on Si and InAs quantum dots: for these materials as well, the increase in Coulombic interaction is more than compensated by the decrease of the density of states. This indicates that the above argumentation can be extended to other materials beyond PbSe and PbS.

Our combined experimental and theoretical efforts demonstrate that quantum-confinement effects do not enhance carrier multiplication in quantum dots; in fact, for a given photon energy, carrier multiplication is more efficient in bulk materials. Our observations are consistent with a scenario where in both quantum dots and bulk, carrier multiplication is governed by impact ionization, the rate of which is reduced by quantum confinement owing to a reduction of the density of states. For the application of quantum dots in solar cells, carrier multiplication with sub-bulk efficiencies may still be beneficial because extra carriers can be exploited at higher voltages (Egap,QD is always larger than Egap,bulk). However, our work demonstrates that quantum confinement does not lead to further benefits resulting from higher carrier-multiplication efficiencies.

Methods

Calculation of the carrier-multiplication efficiency from THz-TDS data.

The carrier-multiplication efficiency in PbS was calculated by determining the number of photogenerated electron–hole pairs using THz-TDS measurements, in combination with accurate determination of the number of absorbed photons. The photoconductivity data in Fig. 1a were measured at a 266 nm excitation fluence of 15.2 nJ mm−2. This fluence corresponds to 9.56×109 absorbed photons per square millimetre, taking the 266 nm reflectance at the PbS surface into account. The data in Fig. 1a (measured at a pump–probe delay of 10 ps) were fitted with the Drude expression, yielding a plasma frequency of ωp=3.30×1014 Hz. From the value of ωp, a carrier density of 6.85×1024 m−3 is calculated, given the electron and hole effective masses (me∼mh∼0.20 at room temperature)30. Using the 266 nm penetration depth of PbS, the carrier density is converted into a sheet density of 2.92×1010 electron–hole pairs per square millimetre. Here, we also took into account that in PbS, both electrons and holes make comparable contributions to ΔE(t) because of their similar effective masses. Dividing the sheet density by the number of absorbed photons per square millimetre yields η, the number of electron–hole pairs per absorbed photon. For 266 nm excitation, η was found to be 3.05±0.15 electron–hole pairs per absorbed photon.

Tight-binding calculations.

The method of the tight-binding calculations is basically as described in our previous work20 but using a slightly simplified numerical procedure. We define a linear grid in energy (energy spacing=5 meV) instead of the real band energy levels. As we consider a finite grid, the number of channels for the relaxation is large but the calculation remains tractable numerically. We suppose that all of the possible channels for the relaxation by impact ionization are characterized by the same rate that is given by the total impact ionization rate (given in ref. 20) divided by the number of channels. This approximation is justified by the huge number of accessible channels for the relaxation and we checked that it predicts carrier-multiplication efficiencies in excellent agreement with our previous simulations for quantum dots at lower computational cost.

References

Nozik, A. J. Quantum dot solar cells. Physica E 14, 115–120 (2002).

Schaller, R. D. & Klimov, V. I. High efficiency carrier multiplication in PbSe nanocrystals: Implications for solar energy conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 186601 (2004).

Klimov, V. I. Spectral and dynamical properties of multiexcitons in semiconductor nanocrystals. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58, 635–673 (2007).

Trumm, S. et al. Ultrafast spectroscopy of impact ionization and avalanche multiplication in GaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 132113 (2006).

Ellingson, R. J. et al. Highly efficient multiple exciton generation in colloidal PbSe and PbS quantum dots. Nano Lett. 5, 865–871 (2005).

Schaller, R. D., Agranovich, V. M. & Klimov, V. I. High-efficiency carrier multiplication through direct photogeneration of multi-excitons via virtual single-exciton states. Nature Phys. 1, 189–194 (2005).

Schaller, R. D., Sykora, M., Pietryga, J. M. & Klimov, V. I. Seven excitons at a cost of one: Redefining the limits for conversion efficiency of photons into charge carriers. Nano Lett. 6, 424–429 (2006).

Trinh, M. T. et al. In spite of recent doubts carrier multiplication does occur in PbSe nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 8, 1713–1718 (2008).

Ji, M. et al. Efficient multiple exciton generation observed in colloidal PbSe quantum dots with temporally and spectrally resolved intraband excitation. Nano Lett. 9, 1217–1222 (2009).

Murphy, J. E. et al. PbTe colloidal nanocrystals: Synthesis, characterization, and multiple exciton generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3241–3247 (2006).

Schaller, R. D., Petruska, M. A. & Klimov, V. I. Effect of electronic structure on carrier multiplication efficiency: Comparative study of PbSe and CdSe nanocrystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 253102 (2005).

Beard, M. C. et al. Multiple exciton generation in colloidal silicon nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 7, 2506–2512 (2007).

Pijpers, J. J. H. et al. Carrier multiplication and its reduction by photodoping in colloidal InAs quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 4146–4152 (2007).

Schaller, R. D., Pietryga, J. M. & Klimov, V. I. Carrier multiplication in InAs nanocrystal quantum dots with an onset defined by the energy conservation limit. Nano Lett. 7, 3469–3476 (2007).

Nair, G. & Bawendi, M. G. Carrier multiplication yields of CdSe and CdTe nanocrystals by transient photoluminescence spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 76, 081304 (2007).

Pijpers, J. J. H. et al. Carrier multiplication and its reduction by photodoping in colloidal InAs quantum dots. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 4783–4784 (2008).

Ben-Lulu, M. et al. On the absence of detectable carrier multiplication in a transient absorption study of InAs/CdSe/ZnSe core/shell1/shell2 quantum dots. Nano Lett. 8, 1207–1211 (2008).

Nair, G., Geyer, S. M., Chang, L.-Y. & Bawendi, M. G. Carrier multiplication yields in PbS and PbSe nanocrystals measured by transient photoluminescence. Phys. Rev. B 78, 125325 (2008).

McGuire, J. A. et al. New aspects of carrier multiplication in semiconductor nanocrystals. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1810–1819 (2008).

Allan, G. & Delerue, C. Role of impact ionization in multiple exciton generation in PbSe nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205423 (2006).

Smith, A. & Dutton, D. Behavior of lead sulfide photocells in the ultraviolet. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 48, 1007–1009 (1958).

Klimov, V. I. & McBranch, D. W. Femtosecond 1P-to-1S electron relaxation in strongly confined semiconductor nanocrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 4028–4031 (1998).

Guyot-Sionnest, P., Shim, M., Matranga, C. & Hines, M. Intraband relaxation in CdSe quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 60, R2181–R2184 (1999).

Pandey, A. & Guyot-Sionnest, P. Slow electron cooling in colloidal quantum dots. Science 322, 929–932 (2008).

Jeon, T.-I. & Grischkowsky, D. Nature of conduction in doped silicon. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1106–1109 (1997).

Beard, M. C., Turner, G. M. & Schmuttenmaer, C. A. Terahertz spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 7146–7159 (2002).

Hendry, E., Koeberg, M., Pijpers, J. & Bonn, M. Reduction of carrier mobility in semiconductors caused by charge–charge interactions. Phys. Rev. B 75, 233202 (2007).

Franceschetti, A., An, J. M. & Zunger, A. Impact ionization can explain carrier multiplication in PbSe quantum dots. Nano Lett. 6, 2191–2195 (2006).

Rabani, E. & Baer, R. Distribution of multiexciton generation rates in CdSe and InAs nanocrystals. Nano Lett. 8, 4488–4492 (2008).

Barton, C. F. Electron effective mass in PbS single crystals by infrared reflectivity measurements. J. Appl. Phys. 42, 445–450 (1971).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Vanmaekelbergh, C. de Mello Donegá and A. Houtepen for useful discussions. This work is part of the Joint Solar Programme (JSP) of the Stichting voor Fundamenteel Onderzoek der Materie FOM, which is supported financially by Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO). The JSP is co-financed by gebied Chemische Wetenschappen of NWO and Stichting Shell Research. This work has been partially supported by the Israel Science Foundation under Grant no. 1298/07.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.J.H.P., R.U. and K.J.T. carried out experimental work and analysed data; A.O. and Y.G. prepared the samples; C.D. and G.A. carried out theoretical calculations; M.B. designed the research; J.J.H.P. and M.B. did project planning and main writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information (PDF 375 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pijpers, J., Ulbricht, R., Tielrooij, K. et al. Assessment of carrier-multiplication efficiency in bulk PbSe and PbS. Nature Phys 5, 811–814 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1393

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys1393

This article is cited by

-

Spin-exchange carrier multiplication in manganese-doped colloidal quantum dots

Nature Materials (2023)

-

Carrier multiplication in van der Waals layered transition metal dichalcogenides

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Low threshold and efficient multiple exciton generation in halide perovskite nanocrystals

Nature Communications (2018)

-

Thermoelectric transport properties of Pb–Sn–Te–Se system

Rare Metals (2018)

-

Charge carrier localised in zero-dimensional (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 clusters

Nature Communications (2017)