Abstract

Interactions between microorganisms shape microbial ecosystems. Systematic studies of mixed microbes in co-culture have revealed widespread potential for growth inhibition among marine heterotrophic bacteria, but similar synoptic studies have not been done with autotroph/heterotroph pairs, nor have precise descriptions of the temporal evolution of interactions been attempted in a high-throughput system. Here, we describe patterns in the outcome of pair-wise co-cultures between two ecologically distinct, yet closely related, strains of the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus and hundreds of heterotrophic marine bacteria. Co-culture with the collection of heterotrophic strains influenced the growth of Prochlorococcus strain MIT9313 much more than that of strain MED4, reflected both in the number of different types of interactions and in the magnitude of the effect of co-culture on various culture parameters. Enhancing interactions, where the presence of heterotrophic bacteria caused Prochlorococcus to grow faster and reach a higher final culture chlorophyll fluorescence, were much more common than antagonistic ones, and for a selected number of cases were shown to be mediated by diffusible compounds. In contrast, for one case at least, temporary inhibition of Prochlorococcus MIT9313 appeared to require close cellular proximity. Bacterial strains whose 16S gene sequences differed by 1–2% tended to have similar effects on MIT9313, suggesting that the patterns of inhibition and enhancement in co-culture observed here are due to phylogenetically cohesive traits of these heterotrophs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

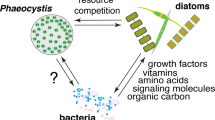

Interactions, such as symbiosis, competition and allelopathy are a central feature of microbial communities (Bassler and Losick, 2006; Azam and Malfatti, 2007; Hibbing et al., 2009). Even in dilute oceanic environments, microbial interactions abound: antagonistic interactions can promote biodiversity (Czaran et al., 2002; Bidle and Falkowski, 2004; Pernthaler, 2005), and synergistic interactions can provide sources of sustenance in complex communities (Azam et al., 1983; Boetius et al., 2000; Croft et al., 2005; Azam and Malfatti, 2007; Amin et al., 2009; Tripp et al., 2010). Although marine microbial interactions often occur on scales of nanometers or microns (Blackburn et al., 1998; Stocker et al., 2008; Malfatti and Azam, 2009; Seymour et al., 2010), they ultimately affect entire ecosystems and global biogeochemical cycles (Azam and Malfatti, 2007).

Heterotrophic bacteria have been shown to both enhance and inhibit the growth of marine and freshwater algae (Grossart et al., 2006; Grossart and Simon, 2007; Mayali et al., 2008) and cyanobacteria (Bratbak and Thingstad, 1985; Manage et al., 2000; Morris et al., 2008) in liquid culture and on solid media. Through these and similar studies we have come to recognize specific mechanisms of interaction, which can occur in the marine environment, such as facilitation of iron uptake (Amin et al., 2009; D’Onofrio et al., 2010), transfer of essential vitamins (Croft et al., 2005), inter- and intra-specific communication (Bassler and Losick, 2006; Vardi et al., 2006) and allelopathy (Mayali et al., 2008; Hibbing et al., 2009). Hypothesizing that bacterium–bacterium antagonistic interactions shape microbial community structure at the microscale, Long and Azam (2001) analyzed interactions among 86 pairs of co-isolated marine bacteria on solid media, revealing the widespread distribution of the potential for growth inhibition among these bacterial strains (Long and Azam, 2001; Grossart et al., 2004; Rypien et al., 2009). More recently, several strains of heterotrophic bacteria have been shown to enhance the growth of a number of ecotypes of Prochlorococcus—the dominant phototroph in temperate and tropical oceans (Coleman and Chisholm, 2007; Partensky and Garczarek, 2010)—at low cell concentrations on solid and liquid media (Morris et al., 2008). It was shown that the mechanism of enhancement in this case was the reduction of oxidative stress, explaining in part long-standing anecdotal observations that culturing Prochlorococcus is usually more robust when indigenous bacterial contaminants are present.

While Prochlorococcus have been extensively studied vis-à-vis the role of environmental factors, such as light, temperature and nutrient availability in shaping their ecology (Moore et al., 1998, 2002; Bouman et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2006; Coleman and Chisholm, 2007), and ‘top down’ processes, such as predation and viral lysis have also been studied to some degree (Lindell et al., 2005, 2007; Sullivan et al., 2005; Frias-Lopez et al., 2009), systematic studies of their interaction with heterotrophic bacteria are limited to that of Morris and Zinser (Morris et al., 2008) described above, who focused on the growth-enhancing role of bacteria in low-density cultures of Prochlorococcus. Inspired by this work, and by systemic analyses of Long and Azam (2001), we undertook a broad-based and quantitative analysis of co-cultures of two axenic Prochlorococcus ecotypes (Saito et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2005) with hundreds of diverse heterotrophic bacteria, examining the response of the Prochlorococcus cells to the presence of bacteria over the entire growth curve of the cultures.

We chose two strains of Prochlorococcus, one adapted to low light (MIT9313) and one adapted to high light (MED4), for these studies because they are ecologically and phylogenetically distinct. Additionally, MIT9313 is known to produce a diverse array of secondary metabolites of unknown function, whereas the genes encoding this system are absent in MED4 (Li et al., 2010). We paired each strain with each of 344 strains of heterotrophic bacteria isolated from an oligotrophic marine environment. We asked: (1) how does the presence of added heterotrophic bacteria influence the growth of each Prochlorococcus strain over the course of its growth curve? (2) Do the two ecotypes respond differently to the presence of the same heterotroph? (3) Do different strains of heterotrophs have different effects, and are they related to the phylogeny of the heterotrophs? (4) Are the observed interactions mediated by soluble compounds or do they require close cellular proximity or contact?

Although the experimental system does not mimic the natural environment in many ways (Supplementary Information), it reveals some fundamental differences between the responses of two Prochlorococcus ecotypes to co-culture with hundreds of bacteria—differences that may hold clues to factors governing their realized niches in the ocean. It further highlights a strong correlation of the outcome of co-culture with the phylogeny of the heterotrophic bacteria, yielding hypotheses for further study on the mechanisms of these interactions and their potential role in marine microbial communities.

Materials and methods

We isolated heterotrophic bacteria from the Hawaii Ocean Time Series (HOT) station ALOHA (22°45′ N, 158° W), one of the most comprehensively studied sites in the ocean, with a microbial community dominated by Prochlorococcus and characterized in some detail (DeLong et al., 2006). The heterotrophs were re-streaked for purity three times, and the final library was preserved at −80 °C in 25% glycerol. Prochlorococcus strains MIT9313 and MED4 were isolated from the Gulf Stream and the Mediterranean Sea, respectively (Rocap et al., 2003), and were maintained in the lab at 20 °C and 27 μE constant cold white illumination. Co-culture was initiated by adding 2 μl of an overnight culture of each heterotroph from the library to 200 μl of Prochlorococcus culture (106 cells ml–1) in 96-well plates. The culture media was Pro99 (Moore et al., 2007) with the addition of 0.01% w/v pyruvate, acetate, lactate and glycerol as well as a vitamin mix (Morris et al., 2008). The co-culture plates were maintained for 42 days at 20 °C and 27 μE constant cold white illumination, and the bulk chlorophyll fluorescence (FL) (ex440 em680) measured almost daily using a Bio-Tek Synergy HT plate reader. The resulting curves were filtered to retain consistent curves, defined as those in which the Euclidian distance between normalized curves fell within the range defined by 95% of the between-plate replicates of axenic curves. The growth parameters were extracted from the growth curves using macros written in Excel VBA, which are available from the investigators on request. Hierarchical Clustering was performed in Matlab. For detailed materials and methods see Supplementary Information.

Results and Discussion

Differences between Prochlorococcus MIT9313 and MED4 in outcome of co-culture

To determine what kinds of interactions occur when Prochlorococcus is grown in co-culture with many different strains of bacteria, we constructed a ‘library’ of 344 heterotrophic bacterial isolates from seawater collected in the open ocean, at the HOT station ALOHA (22°45′ N, 158° W) (Supplementary Figure 1). The heterotrophic strains were isolated on solid media (see Supplementary Information) and consist of at least 65 unique ribotypes (based on partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequences) clustering into 23, 13, 8 and 6 distinct OTUs at 1%, 3%, 5% and 7% ribosomal DNA sequence divergence, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). The strains belong to the gamma-proteobacteria (primarily Alteromonas, Marinobacter and Alcanivorax) and alpha-proteobacteria (Rhodobacter) classes. Each of the 344 heterotrophic strains was inoculated into co-culture with axenic Prochlorococcus strains MED4 and MIT9313 in 96-well plates (under our conditions the outcome of co-culture does not depend on the initial number of heterotrophs inoculated—see Supplementary Information, Supplementary Figure 2). We measured the bulk in vivo chlorophyll FL of the cultures, which is widely used (Grossart, 1999; Mayali et al., 2008; Malmstrom et al., 2010) to follow the dynamics of phytoplankton cultures in a non-invasive manner. Although FL is only proportional to cell number when the cultures are in balanced growth (log phase, see Supplementary Information), the shape of the FL curve can reveal differences between the bulk behavior of the cultures throughout the culture period.

From the hundreds of co-cultures analyzed, only a few general types of co-culture outcomes emerged, as defined by the shape of the FL curves (Figure 1). Fifty-seven percent of the MIT9313 co-cultures fell into the group described as ‘early’ (green, Figure 1b) as these cultures entered exponential growth earlier, and reached higher maximal FL than the heterotroph-free MIT9313 cultures (Figure 1c). A small fraction of the co-cultures (3%) displayed the same initial timing as the ‘early’ group, but FL stopped increasing at an early stage and then declined rapidly (‘early arrested’, purple, Figure 1b). Thirty-four percent of the cultures stopped increasing in FL after 2–3 days, declined to undetectable levels, and then increased again much later (the ‘late’ group, red, Figure 1b). Finally, only 6 % of the co-cultures with MIT9313 behaved similarly to the heterotroph-free cultures (‘intermediate’, black, Figure 1b).

Features of Prochlorococcus MED4 and MIT9313 growth patterns in response to co-culture with 250 different strains of heterotrophic bacteria. (a) Heat maps of the normalized FL of all 338 growth curves (250 co-cultures and 88 controls) as clustered using hierarchical clustering (HC). A clearly different pattern can be seen between four major clusters in MIT9313 but only two in MED4. (b, c) FL curves of the 250 co-cultures (b) and 88 axenic Prochlorococcus cultures (c). The curves are colored as shown in the legend based on the clustering results in panel (a). Four different types of curves, which differ in their growth timing and maximal FL, can be observed for MIT9313, whereas only two clusters are observed for MED4. Note the similarity in the shape of the ‘early arrested’ outcome between MIT9313 and MED4.

The synoptic response of MED4 to co-culture with the same library of bacterial strains was dramatically different from that of MIT9313. Ninety-eight percent of the heterotroph culture collection revealed no clear effect on the growth of MED4—as evidenced by their ‘intermediate’ growth patterns, which are very similar to the heterotroph-free cultures. The growth of Prochlorococcus MED4 in the remaining 2% of the co-cultures was arrested early, displaying strong inhibition by the presence of these heterotrophs (Figure 1b). The heterotrophic bacterial strains that inhibited MED4 were the same strains that defined the ‘early arrested’ group in the MIT9313 cultures.

Quantifying the parameter space of the MED4 and MIT9313 co-culture outcomes

To provide a quantitative estimate of the effect of the microbial interactions can have on Prochlorococcus culture dynamics, we extracted from the FL curves shown in Figure 1 biologically relevant descriptive parameters (similar to those used by Warringer et al. (2008)): the maximum growth rate (μ), the time it took the cultures to reach half of the maximal FL (T50), and the maximum FL (Fmax). As was clear in the qualitative analysis, the parameter space is not homogenously covered (Figure 2; Supplementary Figures 3 and 4). Rather, parts of the parameter space are densely populated, whereas others regions are empty or sparse, representing parameter combinations that are not observed in our co-culture curves (for example, co-cultures in which the log phase growth rate was significantly reduced compared with heterotroph-free cultures).

The quantitative three-dimensional parameter spaces defining the effect co-culture on Prochlorococcus MIT9313 and MED4. A three-dimensional parameter space is shown, with the axes being the maximum growth rate (μ), the time it took the cultures to reach half of the maximal FL (T50), and the maximum FL (Fmax). The parameter spaces shown includes both the co-cultures and the control axenic cultures, and are normalized to axenic wells on the same plates (that is, values larger than one represent an increase in the relevant parameter compared with axenic culture, smaller than one represent a decrease). The data points are colored based on the clustering shown in Figure 1. Large circles represent the median coordinates of each co-culture outcome.

While the growth rate in log phase was influenced by the presence of bacteria in most of the MIT9313 co-cultures, the median of this parameter actually increased in most of the types of co-culture outcomes compared with the heterotroph-free cultures (Supplementary Figure 3) even when the overall effect was clearly one of much later onset of growth. Therefore, in agreement with other studies (Warringer et al., 2008), our results suggest that a combination of different growth parameters is necessary in order to fully describe the complex effect of microbial interactions.

As described above, the most striking is the difference between the large parameter space inhabited by MIT9313 co-cultures and the much more limited space inhabited by MED4 co-cultures (Figure 2). The suite of heterotrophic bacteria that strongly influences the growth of MIT9313, decreasing some parameters up to 10-fold or increasing them up to 4-fold has minimal, if any, impact on MED4.

Heterotroph phylogeny and co-culture outcome

We next asked whether closely related bacteria, as defined by their partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequence (ribotype), affect the growth of Prochlorococcus cultures similarly. As shown in Figure 3, the heterotroph ribotypes, which induced ‘early’, ‘early arrested’ and ‘late growth’ phenotypes were significantly different for MIT9313 (UniFrac test with Bonferroni correction, P⩽0.06; Lozupone and Knight, 2005), as were the groups that induced ‘intermediate’ and ‘early inhibited’ for MED4 (P⩽0.01). For example, all but two of the heterotrophic strains, which induced a ‘late’ outcome of MIT9313 belong to two well-defined clades of Alteromonads (Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 1). Similarly, the same strains induced the ‘early arrested’ outcome in both MED4 and MIT9313, and all of these strains belong to a well-defined clade of Rhodobacters, similar to Marinovum algicola and Ruegeria sp. In most of these cases, the differentiation between strains, which inhibit Prochlorococcus in co-culture and strains, which do not is relatively deep-rooted, within the resolution afforded by our cultured collection of heterotrophs. For example, two Alteromonad clades differing by 1–2% in their partial 16S sequence both inhibit MIT9313, whereas a third clade, which differs by 4–5% from these two clades enhances MIT9313. Similarly, the clade of Rhodobacters inducing ‘early arrested’ phenotype differs from the most closely related strains in our collection that do not induce this phenotype by about 4% in their 16S. This level of divergence corresponds to one commonly used to delineate species or genus level differentiation (Schloss and Handelsman, 2005).

The relationship between patterns observed in co-cultures and the ribotype of the heterotroph. A maximum likelihood (ML) tree (partial 16S rDNA sequences) is shown, with the co-culture outcome (as defined in Figure 1) shown for MIT9313 (middle ring) and MED4 (outer ring). Spheres on the tree branches denote >80% approximate Likelihood Ratio Test (aLRT) confidence (Anisimova and Gascuel, 2006). Different shading of the branches of the tree denotes operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 0.01 resolution (see also Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Asterisks denote the phylogenetic position of strains used for the experiments shown in Figure 4.

Co-culture outcome and proximity of cells

Although many interactions between microorganisms are mediated by diffusible soluble compounds, some have also been observed to occur when cells live in close proximity or even necessitate direct cell–cell contact (Mayali and Azam, 2004; Croft et al., 2005). To test whether close cell–cell proximity is necessary for the different co-culture outcomes observed with MIT9313, we selected five heterotroph strains representing different phylogenetic clades and co-culture outcomes, and co-cultured them with MIT9313 either separated by a membrane permeable to small molecules or mixed together as in the experiment presented above. As shown in Figure 4, when the FL of the co-cultures increased earlier than that of the axenic cultures this happened regardless of whether or not the heterotrophic bacteria were separated from MIT9313 by a membrane. Thus, the ‘early’ outcome of Prochlorococcus cultures is likely mediated in these cases by soluble, diffusible compounds, although we cannot preclude the possibility that the small number of heterotrophic bacteria than can cross the membrane during these 19-day long experiments (see Supplementary Information) may also directly impact the growth of MIT9313. In contrast, the late co-culture outcome occurred only when MIT9313 and Alteromonas strain HOTo1A3 were grown in close proximity and not when they were separated by a membrane.

Comparison of outcomes of co-culture experiments between Prochlorococcus MIT9313 and five strains of bacteria grown together in mixed culture or separated by a 0.4 μm permeable membrane. Results shown are averages and s.d. (n=4 for axenic MIT9313, n=2 for co-cultures). The phylogenetic positions of the strains used in this experiment are shown in Figure 3 as asterisks.

Potential mechanisms underlying different co-culture outcomes

MIT9313 and MED4 represent two taxonomic extremes within the Prochlorococcus lineage, differing by ∼3% in their 16S rRNA sequence. MED4 is a small cell with a highly streamlined genome, and is a member of the high-light adapted clade of Prochlorococcus. MIT9313, in contrast, is a slightly larger cell with a larger genome, and is better adapted for growth at the low light levels found deeper in the water column (Moore et al., 1998, 2002; Rocap et al., 2003; Bouman et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2006; Coleman and Chisholm, 2007). Both strains are growing in these experiments below their respective temperature and light optima (although closer to those of MIT9313, (Rocap et al., 2003; Zinser et al., 2007)), but have been pre-acclimated to the experimental conditions for >7 months (∼120 generations) and thus the difference in co-culture outcome is likely not caused by a general stress response in one strain because of culture conditions.

The ‘early’ culture outcome is the one most commonly observed with MIT9313, is widely distributed among the different phylogenetic groups, and in all cases tested is caused by soluble, diffusible molecules. This is consistent with a ‘helper’ effect where the growth of Prochlorococcus increases as a result of basic attributes common to many lineages of heterotrophic cells, as suggested by Morris et al. (2008). Such attributes may include scavenging of reactive oxygen species (Morris et al., 2008), increasing carbon dioxide concentration (Moore et al., 2007) or cycling waste products. MED4 as a high-light adapted strain, may be better adapted to deal with oxidative stress (often generated during photosynthesis) than MIT9313, thus the latter strain may benefit more from interacting with heterotrophs. Notably, however, MED4 can readily form colonies on solid media only with the help of heterotrophs, and thus this strain is not immune to the effect of co-occurring bacteria (Morris et al., 2008).

In contrast, inhibition of MIT9313 (early arrested or late outcomes) was observed mainly in co-cultures with two well-defined groups of bacteria belonging to the Alteromonads and Rhodobacters, with the latter group being the only one to clearly affect the growth of MED4 under our conditions. Related bacteria have previously been shown to inhibit other microbes through the production of secreted allelochemicals (for example, Mayali and Azam, 2004; Gram et al., 2009). An intriguing observation is that inhibition of MIT9313 by an Alteromonas strain required proximity between the heterotrophic bacteria and MIT9313—that is, the effect could not be mimicked when the cells were kept apart by a semi-permeable membrane. Recently, close physical association (cell–cell contact) has been observed in natural seawater samples between Synechococcus cells, which are closely related to Prochlorococcus, and heterotrophic bacteria of unknown taxonomy (Malfatti and Azam, 2009; Malfatti et al., 2010). These observations suggest the potential for close or contact-mediated interactions even in tiny picoplankton cells.

Conclusions

Although some features of our experimental system limit extrapolation of our results to the experience of wild Prochlorococcus—for example, the co-cultured strains were not co-isolated and the cell densities were higher than found in the wild (see also Supplementary Information)—our study has revealed some properties of these microbial interaction that likely have ecological relevance. First, the two Prochlorococcus ecotypes display fundamentally different responses to the presence of bacteria, both in terms of general patterns, and in terms of specific responses to specific bacterial strains. These differences could influence the connectivity of these two strains within the microbial network in the wild. If so, MIT9313 may be more susceptible to changes in the microbial community than MED4. Similar trends have been suggested for other marine bacterioplankton based on network analysis of patterns of co-occurrence in the oceans (Fuhrman and Steele, 2008).

Second, both the antagonistic and enhancing interactions in our system revealed a clear phylogenetic signature, with closely related bacteria causing similar responses in the co-cultured Prochlorococcus. Furthermore, only a handful of different interaction types, as measured through their effect on Prochlorococcus growth curves, were observed. The heterotroph culture collection we used represents only a fraction of diversity found in the oceans, and does not include many of the most common lineages. Future work with a wider diversity of bacteria may either reveal additional types of interactions or highlight unknown constrains on the types of interactions, which can affect cells in the aquatic environment.

Considering the high levels of microheterogeneity in both marine microbial populations (Thompson et al., 2005; Hunt et al., 2008) and their environment (Blackburn et al., 1998; Azam and Malfatti, 2007; Stocker et al., 2008; Seymour et al., 2010), the task of understanding how complex microbial populations interact in the oceans is a daunting one. Although it is encouraging, as we seek general patterns, that the co-culture outcomes we observe are not random with respect to the phylogeny of the heterortophs, the opposite has been observed in cultures of interacting heterotrophic bacteria (Long and Azam, 2001). Clearly expanded and in depth study of the network of possible interactions between microbial groups is essential, if we ever wish to incorporate microbial interactions into our understanding of marine microbial communities.

References

Amin SA, Green DH, Hart MC, Kupper FC, Sunda WG, Carrano CJ . (2009). Photolysis of iron-siderophore chelates promotes bacterial-algal mutualism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17071–17076.

Anisimova M, Gascuel O . (2006). Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: a fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst Biol 55: 539–552.

Azam F, Fenchel T, Field JG, Gray JS, Meyerreil LA, Thingstad F . (1983). The ecological role of water-column microbes in the sea. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 10: 257–263.

Azam F, Malfatti F . (2007). Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 782–791.

Bassler BL, Losick R . (2006). Bacterially speaking. Cell 125: 237–246.

Bidle KD, Falkowski PG . (2004). Cell death in planktonic, photosynthetic microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 2: 643–655.

Blackburn N, Fenchel T, Mitchell J . (1998). Microscale nutrient patches in planktonic habitats shown by chemotactic bacteria. Science 282: 2254–2256.

Boetius A, Ravenschlag K, Schubert CJ, Rickert D, Widdel F, Gieseke A et al. (2000). A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nature 407: 623–626.

Bouman HA, Ulloa O, Scanlan DJ, Zwirglmaier K, Li WK, Platt T et al. (2006). Oceanographic basis of the global surface distribution of Prochlorococcus ecotypes. Science 312: 918–921.

Bratbak G, Thingstad TF . (1985). Phytoplankton-bacteria interactions - an apparent paradox - analysis of a model system with both competition and commensalism. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 25: 23–30.

Coleman ML, Chisholm SW . (2007). Code and context: Prochlorococcus as a model for cross-scale biology. Trends Microbiol 15: 398–407.

Croft MT, Lawrence AD, Raux-Deery E, Warren MJ, Smith AG . (2005). Algae acquire vitamin B-12 through a symbiotic relationship with bacteria. Nature 438: 90–93.

Czaran TL, Hoekstra RF, Pagie L . (2002). Chemical warfare between microbes promotes biodiversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 786–790.

D’Onofrio A, Crawford JM, Stewart EJ, Witt K, Gavrish E, Epstein S et al. (2010). Siderophores from neighboring organisms promote the growth of uncultured bacteria. Chem Biol 17: 254–264.

DeLong EF, Preston CM, Mincer T, Rich V, Hallam SJ, Frigaard NU et al. (2006). Community genomics among stratified microbial assemblages in the ocean's interior. Science 311: 496–503.

Frias-Lopez J, Thompson A, Waldbauer J, Chisholm SW . (2009). Use of stable isotope-labelled cells to identify active grazers of picocyanobacteria in ocean surface waters. Environ Microbiol 11: 512–525.

Fuhrman JA, Steele JA . (2008). Community structure of marine bacterioplankton: patterns, networks, and relationships to function. Aquat Microb Ecol 53: 69–81.

Gram L, Melchiorsen J, Bruhn J . (2010). Antibacterial activity of marine culturable bacteria collected from a global sampling of ocean surface waters and surface swabs of marine organisms. Mar Biotechnol 12: 439–451.

Grossart HP . (1999). Interactions between marine bacteria and axenic diatoms (Cylindrotheca fusiformis, Nitzschia laevis, and Thalassiosira weissflogii) incubated under various conditions in the lab. Aquat Microb Ecol 19: 1–11.

Grossart HP, Czub G, Simon M . (2006). Algae-bacteria interactions and their effects on aggregation and organic matter flux in the sea. Environ Microbiol 8: 1074–1084.

Grossart HP, Schlingloff A, Bernhard M, Simon M, Brinkhoff T . (2004). Antagonistic activity of bacteria isolated from organic aggregates of the German Wadden Sea. Fems Microbiol Ecol 47: 387–396.

Grossart HP, Simon M . (2007). Interactions of planktonic algae and bacteria: effects on algal growth and organic matter dynamics. Aquat Microb Ecol 47: 163–176.

Hibbing ME, Fuqua C, Parsek MR, Peterson SB . (2009). Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 15–25.

Hunt DE, David LA, Gevers D, Preheim SP, Alm EJ, Polz MF . (2008). Resource partitioning and sympatric differentiation among closely related bacterioplankton. Science 320: 1081–1085.

Johnson ZI, Zinser ER, Coe A, McNulty NP, Woodward EM, Chisholm SW . (2006). Niche partitioning among Prochlorococcus ecotypes along ocean-scale environmental gradients. Science 311: 1737–1740.

Li B, Sher D, Kelly L, Shi Y, Huang K, Knerr PJ et al. (2010). Catalytic promiscuity in the biosynthesis of cyclic peptide secondary metabolites in planktonic marine cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10430–10435.

Lindell D, Jaffe JD, Coleman ML, Futschik ME, Axmann IM, Rector T et al. (2007). Genome-wide expression dynamics of a marine virus and host reveal features of co-evolution. Nature 449: 83–86.

Lindell D, Jaffe JD, Johnson ZI, Church GM, Chisholm SW . (2005). Photosynthesis genes in marine viruses yield proteins during host infection. Nature 438: 86–89.

Long RA, Azam F . (2001). Antagonistic interactions among marine pelagic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 4975–4983.

Lozupone C, Knight R . (2005). UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 8228–8235.

Malfatti F, Azam F . (2009). Atomic force microscopy reveals microscale networks and possible symbioses among pelagic marine bacteria. Aquat Microb Ecol 58: 1–14.

Malfatti F, Samo TJ, Azam F . (2010). High-resolution imaging of pelagic bacteria by atomic force microscopy and implications for carbon cycling. ISME J 4: 427–439.

Malmstrom RR, Coe A, Kettler GC, Martiny AC, Frias-Lopez J, Zinser ER et al. (2010). Temporal dynamics of Prochlorococcus ecotypes in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. ISME J 4: 1252–1264.

Manage PM, Kawabata Z, Nakano S . (2000). Algicidal effect of the bacterium Alcaligenes denitrificans on Microcystis spp. Aquat Microb Ecol 22: 111–117.

Mayali X, Azam F . (2004). Algicidal bacteria in the sea and their impact on algal blooms. J Eukaryot Microbiol 51: 139–144.

Mayali X, Franks PJ, Azam F . (2008). Cultivation and ecosystem role of a marine roseobacter clade-affiliated cluster bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 2595–2603.

Moore LR, Coe A, Zinser ER, Saito MA, Sullivan MB, Lindell D et al. (2007). Culturing the marine cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus. Limnol Oceanogr Methods 5: 353–362.

Moore LR, Ostrowski M, Scanlan DJ, Feren K, Sweetsir T . (2005). Ecotypic variation in phosphorus acquisition mechanisms within marine picocyanobacteria. Aquat Microb Ecol 39: 257–269.

Moore LR, Post AF, Rocap G, Chisholm SW . (2002). Utilization of different nitrogen sources by the marine cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Limnol Oceanogr 47: 989–996.

Moore LR, Rocap G, Chisholm SW . (1998). Physiology and molecular phylogeny of coexisting Prochlorococcus ecotypes. Nature 393: 464–467.

Morris JJ, Kirkegaard R, Szul MJ, Johnson ZI, Zinser ER . (2008). Facilitation of robust growth of Prochlorococcus colonies and dilute liquid cultures by ‘helper’ heterotrophic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 4530–4534.

Partensky F, Garczarek L . (2010). Prochlorococcus: advantages and limits of minimalism. Ann Rev Mar Sci 2: 305–331.

Pernthaler J . (2005). Predation on prokaryotes in the water column and its ecological implications. Nat Rev Microbiol 3: 537–546.

Rocap G, Larimer FW, Lamerdin J, Malfatti S, Chain P, Ahlgren NA et al. (2003). Genome divergence in two Prochlorococcus ecotypes reflects oceanic niche differentiation. Nature 424: 1042–1047.

Rypien KL, Ward JR, Azam F . (2009). Antagonistic interactions among coral-associated bacteria. Environ Microbiol 12: 28–39.

Saito MA, Moffett JW, Chisholm SW, Waterbury JB . (2002). Cobalt limitation and uptake in Prochlorococcus. Limnol Oceanogr 47: 1629–1636.

Schloss PD, Handelsman J . (2005). Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 1501–1506.

Seymour JR, Simo R, Ahmed T, Stocker R . (2010). Chemoattraction to dimethylsulfoniopropionate throughout the marine microbial food web. Science 329: 342–345.

Stocker R, Seymour JR, Samadani A, Hunt DE, Polz MF . (2008). Rapid chemotactic response enables marine bacteria to exploit ephemeral microscale nutrient patches. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4209–4214.

Sullivan MB, Coleman ML, Weigele P, Rohwer F, Chisholm SW . (2005). Three Prochlorococcus cyanophage genomes: signature features and ecological interpretations. PLoS Biol 3: e144.

Thompson JR, Pacocha S, Pharino C, Klepac-Ceraj V, Hunt DE, Benoit J et al. (2005). Genotypic diversity within a natural coastal bacterioplankton population. Science 307: 1311–1313.

Tripp HJ, Bench SR, Turk KA, Foster RA, Desany BA, Niazi F et al. (2010). Metabolic streamlining in an open-ocean nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium. Nature 464: 90–94.

Vardi A, Formiggini F, Casotti R, De Martino A, Ribalet F, Miralto A et al. (2006). A stress surveillance system based on calcium and nitric oxide in marine diatoms. PLoS Biol 4: e60.

Warringer J, Anevski D, Liu B, Blomberg A . (2008). Chemogenetic fingerprinting by analysis of cellular growth dynamics. BMC Chem Biol 8: 3.

Zinser ER, Johnson ZI, Coe A, Karaca E, Veneziano D, Chisholm SW . (2007). Influence of light and temperature on Prochlorococcus ecotype distributions in the Atlantic Ocean. Limnol Oceanogr 52: 2205–2220.

Acknowledgements

We thank Daniele Veneziano for help with statistical analyses and two anonymous referees for many constructive remarks. This study was supported by grants from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the NSF, and the US DOE-GTL (to SWC). DS was supported by postdoctoral fellowships from the Fullbright Foundation and the United States—Israel Binational Agricultural Research and Development Fund (Vaadia-BARD Postdoctoral Fellowship Award No. FI-399-2007). NK was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Rothschild Yad Hanadiv Foundation and LC was supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship in biology from the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sher, D., Thompson, J., Kashtan, N. et al. Response of Prochlorococcus ecotypes to co-culture with diverse marine bacteria. ISME J 5, 1125–1132 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phototroph-heterotroph interactions during growth and long-term starvation across Prochlorococcus and Alteromonas diversity

The ISME Journal (2023)

-

Chemotaxis increases metabolic exchanges between marine picophytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria

Nature Microbiology (2023)

-

Improvement of the Cd removal efficiency of a filamentous cyanobacterium Leptolyngbya sp. XZ1 through co-culture with Bacillus sp. S1

Journal of Applied Phycology (2023)

-

A comparative whole-genome approach identifies bacterial traits for marine microbial interactions

Communications Biology (2022)

-

Microbial diversity of co-occurring heterotrophs in cultures of marine picocyanobacteria

Environmental Microbiome (2021)