Abstract

Background:

Insulin resistance (IR) is usually the first metabolic alteration diagnosed in obese children and the key risk factor for development of comorbidities. The factors determining whether or not IR develops as a result of excess body mass index (BMI) are still not completely understood.

Objectives:

This study aimed to elucidate the mechanisms underpinning the predisposition toward hyperinsulinemia-related complications in obese children by using a metabolomic strategy that allows a profound interpretation of metabolic profiles potentially affected by IR.

Methods:

Serum from 60 prepubertal obese children (30 girls/30 boys, 50% IR and 50% non-IR in each group, but with similar BMIs) were analyzed by using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and capillary electrophoresis–mass spectrometry following an untargeted metabolomics approach. Validation was then performed on a group of 100 additional children with the same characteristics.

Results:

When obese children with and without IR were compared, 47 metabolites out of 818 compounds (P<0.05) obtained after data pre-processing were found to be significantly different. Bile acids exhibit the greatest changes (that is, approximately a 90% increase in IR). The majority of metabolites differing between groups were lysophospholipids (15) and amino acids (17), indicating inflammation and central carbon metabolism as the most altered processes in impaired insulin signaling. Multivariate analysis (OPLS-DA models) showed subtle differences between groups that were magnified when females were analyzed alone.

Conclusions:

Inflammation and central carbon metabolism, together with the contribution of the gut microbiota, are the most altered processes in obese children with impaired insulin signaling in a sex-specific fashion despite their prepubertal status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The mechanisms underlying the metabolic derangements observed in many, but not all, obese patients are still only partially understood, with several authors suggesting the need to differentiate between ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ obese subjects, even at early ages.1 Tissue resistance to insulin’s actions (insulin resistance (IR)) has been largely postulated as the initial impairment underlying the onset of the metabolic comorbidities in these patients. Moreover, IR has been suggested to be the cornerstone for the pathophysiological interpretation of the originally named X-syndrome.2

The assessment of IR is still a matter of debate, particularly in the pediatric setting, as most of the indexes and proposed diagnostic criteria are based on those developed in adults and their application in children is far from being unanimously accepted. The so considered ‘gold-standard’ technique for the measurement of IR is the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp, but its use is mainly restricted to investigational facilities and is normally unavailable in the clinical setting. The usual clinic work-up aims to estimate the presence of IR by using some of its surrogate markers in both fasting and post-ingestion serum samples, with the latter being a better estimation of IR.3

The importance of IR in the interpretation of obesity-associated metabolic derangement is particularly relevant in children, as their developmental characteristics (that is, they continue to grow longitudinally with tissue expansion and plasticity, including adipose tissue) determine substantial differences in their metabolic adaptation to obesity.4 One of the most striking differences with adult obesity is that in childhood obesity, impairment of fasting glucose levels is usually absent and if present, it is a delayed finding. Indeed, a rise in insulinemia, both fasting and after glucose ingestion, can be identified as the very initial step of carbohydrate metabolism impairment in obese children.5

On these bases, the study of the metabolic pathways potentially related to insulin sensitivity and the presence or absence of IR in obese children could help to understand its underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. Metabolomic strategies appear to be a valuable tool to achieve these objectives; indeed, metabolomics allows the interpretation of complex metabolic interactions occurring at a molecular level by providing a more thorough readout of the phenotype at a specific moment.6, 7 Several studies using metabolomics have highlighted the presence of a metabolic signature associated to obesity and IR, and report changes in metabolic profiles affecting central carbon metabolism (CCM), including glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle, amino acid and lipid pathways.8, 9 However, conversely to adults, few studies have evaluated IR in obese children.

In the present study, we devised a high throughput and data-driven approach to investigate the mechanisms underpinning obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia in children and to select a subset of representative biomarkers. We then employed a targeted strategy to test and validate the predictive capability of these biomarkers in a larger independent cohort.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

First analysis: fingerprinting study

Sixty prepubertal (Tanner stage I) obese (OB, BMI>+2 SDS according to Spanish standards,10 also>+2 SDS according to the IOTF references for children) Caucasian children (30 girls/30 boys, 50% IR and 50% non-IR in each group) were studied. The anthropometric and metabolic characteristics of the whole cohort, and the IR and non-IR subgroups are displayed in Table 1.

Second analysis: validation study

One hundred prepubertal (Tanner stage I) obese (OB, BMI>+2 SDS according to Spanish standards,10 also>+2 SDS according to the IOTF references for children) Caucasian children (50 girls/50 boys, 50% IR and 50% non-IR in each group) were studied. The anthropometric and metabolic characteristics of the whole cohort and the IR and non-IR subgroups are displayed in Table 1.

Methods

All patients consulted the Department of Endocrinology of the Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesús for being overweight. This is a monographic pediatric hospital for national referral, and thus receives patients from throughout Spain. They were studied to rule-out any underlying pathological condition before enrollment in the study. BMI was recorded and standardized. An oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT; 1.75 g of glucose/kg; maximum 75 g) was performed after an overnight fast with blood samples being obtained at 0, 30, 60 and 120 min for glucose and insulin measurements. Fasting samples were used for HbA1c and lipid profile analysis. Venous blood samples were collected between 08:00 and 09:00 hours after a 12-h overnight fast. After 30 min clotting at room temperature, samples were then centrifuged at 4°C and the serum separated and immediately frozen at 80°C until assayed, as previously reported.11

Patients were classified as IR if they met one or more of the following criteria during the OGTT: fasting insulin>15 μU ml−1; peak insulin>150 μU ml−1 or insulin>75 μU ml−1 120′ after glucose ingestion.12 The area under the curve for glucose and insulin throughout the OGTT was calculated according to the formula: 0.25 × fasting value+0.5 × 30′value+0.75 × 60′value+0.5 × 120′value.13 HOMA index was calculated as follows: glucose (mg dl−1) × insulin (μU ml−1)/405 and whole body insulin sensitivity index as: 10 000/√ fasting glucose × fasting insulin × mean glucose in the OGTT × mean insulin in the OGTT.3

Untargeted and targeted metabolomics analyses

Fingerprinting study

Metabolite extraction and metabolic fingerprinting were achieved by using a multiplatform-based untargeted metabolomics approach that employs a combination of analytical techniques such as liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS), capillary electrophoresis–mass spectrometry (CE–MS) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) from Agilent Technologies (Madrid, Spain) as described previously.14, 15, 16 Samples were prepared and coded such that they were analyzed in random order with the analyst being unaware of the experimental group to avoid any bias. Data quality was assured by using quality control (QC) samples as reported.17 See Supplementary Materials and Methods for further details.

LC–MS and CE–MS data pre-processing

Data were pre-processed using MassHunter Qualitative Analysis (MH Qual B.06.00, Agilent Technologies) and Mass Profiler Professional (MPP B.02.00, Agilent Technologies) software as previously reported.14, 15 The resulting data matrix was then filtered through the Mass Profiler Professional software by retaining the features present in 100% of QC samples with a coefficient of variation (relative s.d., RSD) below 30%, and the features present in 100% of the samples of at least one of the groups under study. Finally, the CE data were normalized respect with to the IS (methionine sulphone). See Supplementary Experimental Procedure for further details.

Data pre-processing and compound identification GC–MS analysis

Data were pre-processed as previously reported.16 In brief, Automated Mass Spectrometry Deconvolution and Identification System (AMDIS version 2.71, http://chemdata.nist.gov/mass-spc/amdis/downloads/) were employed to deconvolute and to simultaneously identify the eluted compounds. Metabolites were identified by comparing their RT, RI and the mass fragmentation patterns with those available in an in-house library comprehensive of both the NIST mass spectral database (version 2008) and Fiehn RTL library (version 2008). Then, MPP software was used to align the data from all samples. The resulting data matrix was then filtered through the MPP software by retaining the features present in 100% of QC samples with a coefficient of variation (CV or relative s.d.) below 40%, and the features present in 100% of the samples of at least one of the groups under study. Finally, data were normalized with respect to the IS (methyl stearate).

Compound identification LC–MS and CE–MS analyses

To putatively identify only the statistically significant compounds, their accurate mass was searched against public databases, that is, METLIN (http://metlin.scripps.edu), KEGG (http://genome.jp/kegg), LIPIDMAPS (http://lipidmaps.org) and HMDB (http://hmdb.ca). Afterwards, the identification was confirmed by means of standards (CE–MS data) and through the interpretation of the MS/MS spectra acquired in a subsequent LC/MS/MS analysis carried out using the same chromatographic conditions outlined previously. In addition, to increase the reliability of metabolite identification, the match score between the experimental isotopic pattern distribution and the compound formula was computed by MH Qual software.

Validation study

Metabolite quantification was performed by a targeted metabolomics approach by using LC–MS and GC–MS from Agilent technologies as described.18 See Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Table 1 for further details.

Statistical analysis

Fingerprinting study

Statistical analysis was carried out by univariate (UVA, MATLAB R2015 software (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, USA)) and multivariate analyses (MVA, SIMCA P+ 12.0.1 software (Umetrics, Umea, Sweden)). For the UVA, parametric (unpaired t-test) or non-parametric (Mann−Whitney U test) tests with a Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate post hoc correction (q =0.05) were applied. For the MVA, data processing strategies (that is, normalization, scaling among others) were employed to improve the overall quality of data as reported,19 and finally log-transformed and Pareto scaled (CE–MS and LC–MS) or ultraviolet scaled (GC–MS) data were used to create multivariate models. Afterwards, unsupervised (principal components analysis) and supervised (orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis, OPLS-DA) analyses were performed to check trends, outliers and to select the variables responsible for the separation showed by the models. Then, the models were statistically validated by the cross-validation tool, using the leave-1/3-out approach to exclude model overfitting. In addition, boys and girls were considered separately to evaluate the contribution of the sex variable. In this case, both UVA and MVA were performed by following the same procedure above outlined. Finally, the percentage of change for the relevant variables resulting from both UVA and MVA was calculated as follows: ((average value in the tested group-average value in reference group)/ average value in reference group) × 100. In the case of non-normally distributed data, the median instead of the mean was employed.

Validation study

Parametric (unpaired t-test) or non-parametric (Mann−Whitney U test) tests with a Benjamini–Hochberg post hoc correction (q=0.05) were performed in MATLAB.

Results

Fingerprinting study

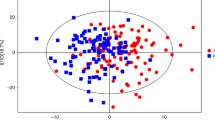

Metabolic fingerprinting yielded the detection of 72 279 potential compounds in serum (LC: 67 617 CE: 4 582 GC: 80). Data filtration was applied by reducing the matrix to 818 compounds (ESI+: 257, ESI-: 315, CE: 196, GC: 50). Then, multivariate and UVA statistical analyses were applied to investigate the comparison between obese children with and without IR. Principal components analysis assured data quality by plotting a clear QC sample clustering (Figure 1a, Supplementary Figure 1). The supervised analyses by OPLS-DA elucidated the discrimination between obese children with IR (group 2) and without IR (group 1). Remarkably, the separation was magnified when only females were considered indicating prepubertal sex differences (Figures 1b and c, Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). Subsequently, the OPLS-DA models were validated and the samples were correctly predicted for 86% in LC (ESI +/-), 83% in GC, 85% in CE. Afterwards, the compounds responsible for the separation found by the models were selected according to the S-plot and the Jack-knife confidence interval (P<0.05). In addition, P-values were computed for the comparison between groups (1 vs 2) in the whole cohort (n=60) and then in males (n=30) and females (n=30). Table 2 includes the 47 identified compounds that showed statistically significant between-group differences after adjustment for multiple testing (that is, P<0.05 and q=0.05). In contrast, 38 out of the 85 compounds statistically significant after adjustment for multiple testing (that is, P <0.05 and q=0.05) remained unidentified. Among the identified compounds, there were 15 amino acids and derivatives, 17 phospholipids (mainly lyso-forms), 3 organic acids, 2 bile acids, 5 fatty acyls, 2 carnitines and 3 other compounds. Bile acids (BAs) and some lysophospholipids (LPs) exhibited the most prominent changes. In contrast, the majority of the metabolites, in particular the amino acids and derivatives, showed subtle difference with a percentage of change between the groups of ~30%. Finally, we observed the same tendency of variation in all comparisons (overall, females and males). Further details are included in Supplementary Table 2.

Multivariate analysis results (unsupervised, principal components analysis (PCA), and supervised, OPLS-DA, models). (a) PCA plot generated from all samples (◊) and QC samples (♦). LC–MS ESI+ data (R2(cum)=0.48, Q2(cum)=0.23). (b) OPLS-DA plot generated from the comparison between obese children with IR (▪) and without IR (□). LC–MS ESI+ data (R2(cum)=0.51, Q2(cum)=0.32). (c) OPLS-DA plot generated from the comparison between obese children with IR (▴) and without IR (Δ). Only female samples are included to generate the model. LC–MS ESI+ data (R2(cum)=0.99, Q2(cum)=0.45). R2= coefficient for variance explained; Q2= coefficient for variance predicted.

Among the compounds showing statistically significant differences between groups in this preliminary study, the 16 most representative metabolites were selected for quantification and verification in a larger independent cohort (IR=50 and non-IR=50). These metabolites included: glycodeoxycholate, taurodeoxycholate, acetylcarnitine (C02-carnitine), 2-methylbutyroylcarnitine (C05-carnitine), pyruvate, 3-hydroxybutyrate, isoleucine, leucine, valine, alanine, phenylalanine, proline, tryptophan, tyrosine, pyroglutamate and piperidine. In addition, the 11 acylcarnitines and 6 amino acids present in the Internal Standard mix (MassChrom Internal Standard Labelled) were included in the validation study.

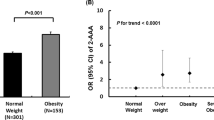

Validation study

After quantification of the metabolites, the P-value was computed for comparison between obese children with IR and without IR (1 vs 2) by considering all samples (n=100) and males (n=50) and females (n=50) separately. In Table 3, only the metabolites that showed significant differences between IR/no-IR after adjustment for multiple testing (that is, P<0.05 and q=0.05) are listed. When the overall cohort is considered, all compounds except C05 and C02-carnitines were confirmed. These differences between groups were more evident in females when the sexes were analyzed separately. Concerning acylcarnitines three, that is, free carnitine (C00), propionylcarnitine (C03) and butyrylcarnitine (C04) were found to be increased significantly in IR for the whole cohort and females, whereas in males only C03-carnitine was increased significantly. Notably, among all compounds only alanine and C03-carnitine were common in all comparisons. Finally, we observed a tendency to increase for the majority of the metabolites, except 3-hydroxybutyrate, free carnitine and pyroglutamate, in the subjects with IR compared with those without IR.

Discussion

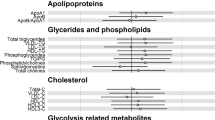

In this study, we have applied a comprehensive untargeted metabolic fingerprinting protocol to gain a deeper understanding of the metabolic pathways potentially associated with alterations in insulin signaling in prepubertal obese children by comparing those with and without IR (1 vs 2). As depicted in Figure 2, the findings of this study can be pooled into three major observations: (1) CCM is one of the metabolic pathways that is most influenced by disturbances in insulin signaling; (2) inflammatory events are enhanced in the presence of IR; and (3) microbiota influence the host metabolism, as pointed out by the marked changes in BAs.

Overview of the changes observed in the metabolic profile of obese children with and without IR. Inflammation and CCM, together with the activity/contribution of the gut microbiota, were found to be altered in obesity-associated hyperinsulinemia. Metabolites that showed significant differences (P< 0.05) between IR and no-IR obese children are depicted in square box. Arrow up: increase; arrow down: decrease relative to control when the whole cohort is investigated. Male (♂) and female (♀) symbols indicate the metabolites that differ significantly between groups, when boys and girls are considered separately. FAO, fatty acid oxidation; LysoPL, Lysophospholipids.

Central carbon metabolism

As expected, CCM, which includes glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid and acylcarnitine metabolism was unveiled as the most altered process in obese children with IR. Indeed, the majority of metabolites statistically differing between groups belong to one or several pathways involved in CCM. Moreover, even though the percentage of change between the insulin resistant and non-insulin resistant state is relatively small, we observed an overall increase in amino acids such as alanine, proline and aromatic amino acids (ArAAs; that is, phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan) and branched chain amino acids (BCAA; that is, leucine, isoleucine and valine) in IR. The relationship between increased amino acids and IR has been previously reported, highlighting higher proteolysis and lower amino acid catabolism induced by hyperinsulinemia; indeed, some amino acids have been suggested as both markers and effectors of IR.20, 21 Among these, the increased levels of BCAAs and related metabolites (ArAA, glutamate, and C3 and C5 acylcarnitines) have consistently emerged in recent years as biomarker of obesity and IR. In 2009, Newgard et al. suggested this cluster to be the metabolic signature of obese subjects and associated their increase with the onset of IR in mice ingesting a high-fat diet.8 This theory has been corroborated by subsequent studies in lean subjects with or without IR and in obese subjects with IR after bariatric surgery or dietary intervention.22, 23 These studies highlighted a discriminant capability for BCAA and related metabolites, in case of obesity and IR, and a further predictive capability for the onset of complications such as cardiovascular disease and T2DM (up to 12 years in advance) and for the effectiveness of treatment.24, 25

Although the involvement of the BCAAs and related metabolites in IR is clear, the mechanisms underlying the onset of IR is still a matter of debate. Two major hypotheses have emerged that propose two pathways associated to IR: mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling and derangement of BCAA metabolism.26 The first hypothesis postulates that permanent activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1/serine kinases pathway mediated by BCAA inactivates insulin receptor substrate-1 and insulin receptor substrate-2, and stimulates pancreatic beta cells to enhance insulin secretion resulting in hyperinsulinemia, beta cell exhaustion and thus risk to develop T2DM. However, the sole activation of this pathway might not be sufficient to cause IR and the subsequent complications, but rather a contributing factor in conjunction with inflammation and hyperinsulinemia. In contrast, the second model identifies the toxic metabolites derived from disrupted BCAA metabolism as the cause of IR. Indeed, it has been reported that increased BCAAs (coming from the diet, low catabolic rate in adipose tissue and insulin-induced proteolysis, among others) promotes their catabolism in liver and skeletal muscle and that their by-products (that is, ketoisocaproic acid, short-chain acylcarnitines and their intermediates) affect glucose and fatty acid oxidation by yielding incompletely oxidized substrates that are involved in mitochondrial stress and impaired insulin signaling.9

Consistent with this model, we found that in addition to the elevation in BCAA, IR obese children had increased levels of ketoisocaproic acid, C3 and C4 acylcarnitines and decreased free carnitine. Moreover, we observed an increased level of ArAAs, which are precursor of serotonin (from tryptophan) and catecholamines (from phenylalanine and tyrosine) in the brain.27 They compete with the BCAA for transport into mammalian cells; therefore, their elevation in serum may indicate a disruption in their transportation into the brain due to an excess of BCAA.

We also observed elevated alanine levels in association with IR in every comparison set studied. Alanine is synthesized in skeletal muscle from pyruvate and other amino acids (mainly BCAAs) via the alanine-glucose cycle. In the liver it is then converted back to pyruvate, which is an intermediate for both the tricarboxylic acid cycle and gluconeogenesis.28 Furthermore, we found an increase in pyruvate and a decrease in 3-hydroxybutyrate, consistent with enhanced glycolysis and reduced ketone body production in the presence of hyperinsulinemia. Hence, our study provides evidence of altered CCM in young children with IR and obesity mainly associated to increased levels of BCAA and related metabolites, which is consistent with the models proposed for adolescents and adults.

Inflammatory processes

Chronic low-grade inflammation has been proposed as a possible link between obesity and IR; their interplay has been extensively investigated unveiling an interchangeable cause-effect relationship. Indeed, it has been reported that obesity and IR trigger inflammation by enhancing the release of free fatty acids and cytokines from adipose tissue and macrophages.29 In the opposite direction, inflammation alters the expression of insulin-related genes leading to impaired insulin signaling.30 Consistent with the literature, we found high levels of LPs characterizing the insulin resistant state. LPs can be generated from glycerophospholipids by the action of phospholipase A2 and reactive oxygen species, and both have been associated with increased inflammatory status.31, 32 Among the LP related compounds, the subgroup of lysophosphocholine is of particular interest, due to both its pro-inflammatory effect and its contribution to insulin signaling impairment.33, 34

In addition to the increase in pro-inflammatory metabolites, we observed a parallel decrease in metabolites such as bilirubin, nitro-octadecenoate, docosahexaenoate and docosapentanoate, all of which have anti-inflammatory properties. Bilirubin exhibits antioxidant activity and inhibits lipid and protein peroxidation;35 whereas nitro-octadecenoate acts as an endogenous anti-inflammatory mediator by interacting with macrophages both by down-regulating lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 expression36 and by inhibiting cytokine release after lipopolysaccharide-stimuli.37 Docosahexaenoate and docosapentanoate, polyunsaturated fatty acids of the omega-3 series, reduce inflammation-related mediators38 and can also influence the IR state. Indeed, it was recently reported that IR is decreased in obese children and adolescents by dietary supplementation with omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids.39, 40 Our results highlight that the unbalanced proportion of pro-inflammatory vs anti-inflammatory effectors characterizing the obese children is exacerbated in the presence of IR driven hyperinsulinemia.

Microbiota influence

Glycodeoxycholate and taurodeoxycholate are greatly increased in the obese subjects with IR when compared with their non-insulin resistant counterparts. These compounds presented the most marked changes, unveiling the influence of the gut microbiota on the host metabolism. Indeed, their presence in plasma is mediated by the action of the microbiota that transforms cholate, conjugated with glycine or taurine, into secondary BAs that are reabsorbed from the distal ileum through the enterohepatic circulation. These secondary BAs then act as signaling molecules through activation of the Farsenoid X receptor and the G-protein coupled receptor TGR5 in peripheral organs (that is, liver and adipose tissue), which regulate the lipid and glucose homeostasis of the host.41 In addition to BAs, piperidine, the by-product of amino acid degradation mediated by the microflora, is also increased in the insulin resistant group. Together these changes in metabolites indicate involvement of the gut microbiota and suggest that it contributes to the development of obesity and its complications. Indeed, compelling evidence has linked the gut microbiota to obesity and obesity-associated inflammation, and IR both in animals and in humans.42 In addition to the aforementioned effect of secondary BAs, the microbiome increases the energy harvest from the diet by generating short-chain fatty acids from undigested starch and modulates energy storage through angiopoietin-like protein4, which is related to the uptake of triglycerides.43 Furthermore, the microbiome can trigger inflammation and subsequent impairment of insulin signaling via a metabolic endotoxemia due to increased production of the endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) present on the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria. Indeed, the gut microbiota, which is altered by obesity, modulates intestinal permeability and increases the passage of lipopolysaccharide into the circulation, which in turn stimulates the pro-inflammatory signaling cascade.42, 44

Obese children are reported to have altered microbiota compared with their lean counterparts45 and the initial composition of the microbiota may have predictive capability for the effects of dietary intervention46 and for the onset of obesity in overweight children.47 Our findings suggest a possible alteration in the microflora in obese children, and they provide additional information regarding the insulin resistant state that seems to be characterized by a magnified contribution of the microbiome on the host metabolome when compared with the non-IR obese state.

Thus, the involvement of the three processes underscored by the present study highlights the multifactorial nature of the interaction between obesity and IR, suggesting that several pathways are altered early on and interact at multiple levels in the development of IR. These pathways and relative metabolites might be a valuable tool in preventing disease progression. Recent studies have described metabolic signatures of human diseases, including diabetes, that occur in response to alterations in the metabolism of amino acids, gut microbiota by-products and lipids8, 48, 49, 50, 51 similar to what occurred at a lesser extent in obese children with IR. This suggests their possible use as a hallmark for the early onset of complications. Current recommendations on early detection of T2DM in children emphasize the difficulties in distinguishing T2DM from T1DM in early stages, particularly in some patients, given the high prevalence of obesity and the possibility of ketoacidosis at the onset of T2DM. Analysis of the metabolites shown by the present study to be, altered in cases of obesity with IR, could be implemented in clinical practice to identify high-risk individuals earlier to delay or prevent disease onset and additionally to allow personalized preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Our study highlights the effect of sex on the IR-mediated alterations; indeed, the significance of these alterations was intensified when females were investigated separately. Girls with IR showed an overall increased concentration of acylcarnitines and amino acids (mainly BCAA) in serum. Previous studies have reported a higher incidence of IR in girls before puberty52, 53 due to differences of sex-linked genes that may explain this intrinsic difference. These findings suggest a female susceptibility toward IR-mediated alterations that is consistent with our results on the metabolic profile of obese girls with IR. In boys the observed changes associated with IR were less intense than in girls. This finding is in contrast to previous studies showing an intensification of the IR-mediated alterations in males. However, the previous studies were performed in adolescents54 and adults,55, 56, 57 where a change in insulin sensitivity was reported according to sex during and after puberty.58 Thus, they might be not representative of what occurs in prepubertal children.

A further strength of this study is the use of the multiplatform metabolomics strategy, by combining both untargeted (fingerprinting) and targeted (validation) approaches, to investigate the effects of IR in a specific population of obese children matched for sex, age and BMI-SDS naïve to drugs and before puberty, thus avoiding sex steroid influences. In addition, the severity of obesity in the studied patients (mean BMI-SDS above +4.5 SDS in all subgroups) enhances the relationship between the observations and the condition of adiposity excess. Therefore, the use of a multiplatform approach, which magnifies the metabolite coverage by enabling the detection of the main classes of metabolites, provided a more comprehensive overview of the pathways altered as detected by the fingerprinting approach and confirmed in the validation study. However some limitations merit consideration. The sample size was relatively small; although it allowed the detection of validated changes in the whole cohort and in the female subgroup, it might not be sufficient to appreciate differences in the male subgroup for which future studies in a bigger cohort are needed. Moreover, serum was employed in the present study instead of tissue samples due to its easy sampling compared with the invasive modality of tissue collection. Serum provides integrated information regarding processes that are simultaneously occurring in the whole organism as it interacts with all tissues. However, it does not reflect the direct metabolic modifications and upstream regulations in response to external/internal stimuli or life-style modifications (that is, diet and physical activity) that can affect obesity and IR.59, 60 Indeed, it would be of great interest to correlate these results with information regarding nutritional status and habits, physical activity and weight evolution, as well as pre- and peri-natal information including breastfeeding and maternal health. In addition, the use of surrogate measures of IR instead of the gold-standard euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp to discriminate between IR and non-IR patients might be considered a limitation. However, the combined use of fasting and post-OGTT parameters can overcome this limitation, as reinforced by the striking differences in HOMA and insulin-AUC between IR and non-IR subgroups both in groups 1 and 2. Further information on the metabolic/metabolomic status of the patients could eventually be obtained in a future study of the metabolomic profile after high dose oral glucose intake. Moreover, the parallel study of gut microbiota in stool samples could help to explain some of the observed changes reported here.

In conclusion, our study provides new insights into the metabolic profile that characterizes two conditions (obesity and IR) highly associated but not unequivocally correlated to the onset of the disease, by shedding light on the possible pathophysiological alterations that might be hallmarks of the predisposing factors toward complications.

References

Bluher S, Schwarz P . Metabolically healthy obesity from childhood to adulthood-does weight status alone matter? Metabolism 2014; 63: 1084–1092.

Reaven GM . Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988; 37: 1595–1607.

Borai A, Livingstone C, Ferns GA . The biochemical assessment of insulin resistance. Ann Clin Biochem 2007; 44: 324–342.

Martos-Moreno GA, Barrios V, Chowen JA, Argente J . Adipokines in childhood obesity. Vitam Horm 2013; 91: 107–142.

Martos-Moreno GA, Barrios V, Martinez G, Hawkins F, Argente J . Effect of weight loss on high-molecular weight adiponectin in obese children. Obesity (Silver Spring) United States 2010; 18: 2288–2294.

Nicholson JK, Lindon JC, Holmes E . 'Metabonomics': understanding the metabolic responses of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli via multivariate statistical analysis of biological NMR spectroscopic data. Xenobiotica 1999; 29: 1181–1189.

Fiehn O . Combining genomics, metabolome analysis, and biochemical modelling to understand metabolic networks. Comp Funct Genomics 2001; 2: 155–168.

Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Stevens RD, Lien LF et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance. Cell Metab United States 2009; 9, p 311–326.

Newgard CB . Interplay between lipids and branched-chain amino acids in development of insulin resistance. Cell Metab 2012; 15: 606–614.

Hernández M, Castellet J, Narvaiza J, Rincón J, Ruiz I, Sánchez E et al. Curvas y Tablas De Crecimiento. Editorial Garsi: Madrid, 1988.

Martos-Moreno GA, Kratzsch J, Korner A, Barrios V, Hawkins F, Kiess W et al. Serum visfatin and vaspin levels in prepubertal children: effect of obesity and weight loss after behavior modifications on their secretion and relationship with glucose metabolism. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011; 35: 1355–1362.

Eyzaguirre F, Mericq V . Insulin resistance markers in children. Horm Res 2009; 71: 65–74.

Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP, Pugh JA, Patterson JK . Hyperinsulinemia in a population at high risk for non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1986; 315: 220–224.

Ciborowski M, Lipska A, Godzien J, Ferrarini A, Korsak J, Radziwon P et al. Combination of LC-MS- and GC-MS-based metabolomics to study the effect of ozonated autohemotherapy on human blood. J Proteome Res 2012; 11: 6231–6241.

Naz S, Garcia A, Rusak M, Barbas C . Method development and validation for rat serum fingerprinting with CE-MS: application to ventilator-induced-lung-injury study. Anal Bioanal Chem 2013; 405: 4849–4858.

Mastrangelo A, Ferrarini A, Rey-Stolle F, García A, Barbas C . From sample treatment to biomarker discovery: a tutorial for untargeted metabolomics based on GC-(EI)-Q-MS. Anal Chim Acta 2015; 900: 21–35.

Dunn WB, Wilson ID, Nicholls AW, Broadhurst D . The importance of experimental design and QC samples in large-scale and MS-driven untargeted metabolomic studies of humans. Bioanalysis 2012; 4: 2249–2264.

Naz S, Calderon AA, Garcia A, Gallafrio J, Mestre RT, Gonzalez EG et al. Unveiling differences between patients with acute coronary syndrome with and without ST elevation through fingerprinting with CE-MS and HILIC-MS targeted analysis. Electrophoresis 2015. e-pub ahead of print 14 July 2015; doi:10.1002/elps.201500169.

Godzien J, Ciborowski M, Angulo S, Barbas C . From numbers to a biological sense: how the strategy chosen for metabolomics data treatment may affect final results. A practical example based on urine fingerprints obtained by LC-MS. Electrophoresis 2013; 34: 2812–2826.

Felig P, Marliss E, Cahill GF Jr . Plasma amino acid levels and insulin secretion in obesity. N Engl J Med 1969; 281: 811–816.

Adams SH . Emerging perspectives on essential amino acid metabolism in obesity and the insulin-resistant state. Adv Nutr 2011; 2: 445–456.

Laferrere B, Reilly D, Arias S, Swerdlow N, Gorroochurn P, Bawa B et al. Differential metabolic impact of gastric bypass surgery versus dietary intervention in obese diabetic subjects despite identical weight loss. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 80re2.

Shah SH, Crosslin DR, Haynes CS, Nelson S, Turer CB, Stevens RD et al. Branched-chain amino acid levels are associated with improvement in insulin resistance with weight loss. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 321–330.

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Cheng S, Rhee EP, McCabe E et al. Metabolite profiles and the risk of developing diabetes. Nat Med 2011; 17: 448–453.

Sears DD, Hsiao G, Hsiao A, Yu JG, Courtney CH, Ofrecio JM et al. Mechanisms of human insulin resistance and thiazolidinedione-mediated insulin sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 18745–18750.

Lynch CJ, Adams SH . Branched-chain amino acids in metabolic signalling and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014; 10: 723–736.

Fernstrom JD . Branched-chain amino acids and brain function. J Nutr 2005; 135: 1539S–1546S.

Felig P . The glucose-alanine cycle. Metabolism 1973; 22: 179–207.

Kim JA, Montagnani M, Koh KK, Quon MJ . Reciprocal relationships between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: molecular and pathophysiological mechanisms. Circulation 2006; 113: 1888–1904.

Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP . Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2008; 9: 367–377.

Triggiani M, Granata F, Frattini A, Marone G . Activation of human inflammatory cells by secreted phospholipases A2. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1761: 1289–1300.

Fuchs B, Schiller J . Lysophospholipids: their generation, physiological role and detection. Are they important disease markers?. Mini Rev Med Chem 2009; 9: 368–378.

Han MS, Lim YM, Quan W, Kim JR, Chung KW, Kang M et al. Lysophosphatidylcholine as an effector of fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Lipid Res 2011; 52: 1234–1246.

Wallace M, Morris C, O'Grada CM, Ryan M, Dillon ET, Coleman E et al. Relationship between the lipidome, inflammatory markers and insulin resistance. Mol Biosyst 2014; 10: 1586–1595.

Sedlak TW, Saleh M, Higginson DS, Paul BD, Juluri KR, Snyder SH . Bilirubin and glutathione have complementary antioxidant and cytoprotective roles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 5171–5176.

Wang G, Ji Y, Li Z, Han X, Guo N, Song Q et al. Nitro-oleic acid downregulates lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 expression via the p42/p44 MAPK and NFkappaB pathways. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 4905.

Cui T, Schopfer FJ, Zhang J, Chen K, Ichikawa T, Baker PR et al. Nitrated fatty acids: endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 35686–35698.

White PJ, Marette A . Is omega-3 key to unlocking inflammation in obesity? Diabetologia 2006; 49: 1999–2001.

Haugaard SB, Madsbad S, Hoy CE, Vaag A . Dietary intervention increases n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in skeletal muscle membrane phospholipids of obese subjects. Implications for insulin sensitivity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006; 64: 169–178.

Juarez-Lopez C, Klunder-Klunder M, Madrigal-Azcarate A, Flores-Huerta S . Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids reduce insulin resistance and triglycerides in obese children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes 2013; 14: 377–383.

Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B . Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev 2009; 89: 147–191.

Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 2008; 57: 1470–1481.

Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004; 101: 15718–15723.

Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007; 56: 1761–1772.

Bervoets L, Van Hoorenbeeck K, Kortleven I, Van Noten C, Hens N, Vael C et al. Differences in gut microbiota composition between obese and lean children: a cross-sectional study. Gut Pathog 2013; 5: 10.

Santacruz A, Marcos A, Warnberg J, Marti A, Martin-Matillas M, Campoy C et al. Interplay between weight loss and gut microbiota composition in overweight adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009; 17: 1906–1915.

Kalliomaki M, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E . Early differences in fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87: 534–538.

Floegel A, Stefan N, Yu Z, Muhlenbruch K, Drogan D, Joost HG et al. Identification of serum metabolites associated with risk of type 2 diabetes using a targeted metabolomic approach. Diabetes 2013; 62: 639–648.

Du F, Virtue A, Wang H, Yang XF . Metabolomic analyses for atherosclerosis, diabetes, and obesity. Biomark Res 2013; 1: 17.

Drogan D, Dunn WB, Lin W, Buijsse B, Schulze MB, Langenberg C et al. Untargeted metabolic profiling identifies altered serum metabolites of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a prospective, nested case control study. Clin Chem 2015; 61: 487–497.

Wewalka M, Patti ME, Barbato C, Houten SM, Goldfine AB . Fasting serum taurine-conjugated bile acids are elevated in type 2 diabetes and do not change with intensification of insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99: 1442–1451.

Murphy MJ, Metcalf BS, Voss LD, Jeffery AN, Kirkby J, Mallam KM et al. Girls at five are intrinsically more insulin resistant than boys: the Programming Hypotheses Revisited—The EarlyBird Study (EarlyBird 6). Pediatrics 2004; 113: 82–86.

Shields BM, Knight B, Hopper H, Hill A, Powell RJ, Hattersley AT et al. Measurement of cord insulin and insulin-related peptides suggests that girls are more insulin resistant than boys at birth. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 2661–2666.

Newbern D, Gumus Balikcioglu P, Balikcioglu M, Bain J, Muehlbauer M, Stevens R et al. Sex differences in biomarkers associated with insulin resistance in obese adolescents: metabolomic profiling and principal components analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99: 4730–4739.

Patel MJ, Batch BC, Svetkey LP, Bain JR, Turer CB, Haynes C et al. Race and sex differences in small-molecule metabolites and metabolic hormones in overweight and obese adults. OMICS 2013; 17: 627–635.

Stancakova A, Civelek M, Saleem NK, Soininen P, Kangas AJ, Cederberg H et al. Hyperglycemia and a common variant of GCKR are associated with the levels of eight amino acids in 9,369 Finnish men. Diabetes 2012; 61: 1895–1902.

Tillin T, Hughes AD, Wang Q, Wurtz P, Ala-Korpela M, Sattar N et al. Diabetes risk and amino acid profiles: cross-sectional and prospective analyses of ethnicity, amino acids and diabetes in a South Asian and European cohort from the SABRE (Southall And Brent REvisited) Study. Diabetologia 2015; 58: 968–979.

Moran A, Jacobs DR Jr, Steinberger J, Steffen LM, Pankow JS, Hong CP et al. Changes in insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk during adolescence: establishment of differential risk in males and females. Circulation 2008; 117: 2361–2368.

Naz S, Moreira dos Santos DC, Garcia A, Barbas C . Analytical protocols based on LC-MS, GC-MS and CE-MS for nontargeted metabolomics of biological tissues. Bioanalysis 2014; 6: 1657–1677.

Want EJ, Masson P, Michopoulos F, Wilson ID, Theodoridis G, Plumb RS et al. Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat Protoc 2013; 8: 17–32.

Acknowledgements

AM is receiving a PhD grant from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness AP-2012-1385. Authors want to express their gratitude to the financial support received from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness MINECO CTQ2014-55279-R, and by Fondos de Investigación Sanitaria and fondos FEDER (Grants PI100747 and PI1302195 to JA), Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (Grants BFU2011–27492 and BFU2014-51836-C2-2-R to JAC), Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Fisiopatología de Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBEROBN), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (JA) and Fundación Endocrinología y Nutrición.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mastrangelo, A., Martos-Moreno, G., García, A. et al. Insulin resistance in prepubertal obese children correlates with sex-dependent early onset metabolomic alterations. Int J Obes 40, 1494–1502 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.92

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.92

This article is cited by

-

Aerobic exercise training and gut microbiome-associated metabolic shifts in women with overweight: a multi-omic study

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Is autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease an early sweet disease?

Pediatric Nephrology (2022)

-

Efficacy of metformin and fermentable fiber combination therapy in adolescents with severe obesity and insulin resistance: study protocol for a double-blind randomized controlled trial

Trials (2021)

-

Metabolomics analysis reveals altered metabolites in lean compared with obese adolescents and additional metabolic shifts associated with hyperinsulinaemia and insulin resistance in obese adolescents: a cross-sectional study

Metabolomics (2021)

-

Metabolite biomarkers of type 2 diabetes mellitus and pre-diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2020)