Abstract

Background:

Use of antiobesity medicines has been linked with serious cardiac and psychiatric adverse events (AEs). Spontaneous reports can provide information about serious, rare and unknown AEs occurring after the time of marketing. In Europe, information about AEs reported for antiobesity medicines can be accessed in the EudraVigilance (EV) database. Therefore, we aimed to identify and characterise AEs associated with the use of antiobesity medicines in Europe.

Methods:

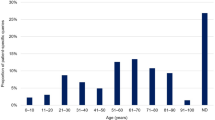

AE reports submitted for antiobesity medicines (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) group A08A) from 2007 to 2014 and located in the EV database were analysed. AE data were categorised with respect to time, age and sex of patient/consumer, type of reporter, category and seriousness of reported AEs and medicines. Consumer AE reports were compared with reports from other types of reporters with respect to age and sex of consumer, seriousness, system organ class and medicine. The unit of analysis was one AE and one AE report, respectively.

Results:

We located 4941 AE reports corresponding to 13 957 AEs for antiobesity medicines in the EV database. More than 90% of all AE cases were serious, including 159 deaths. The majority of AE cases were reported for female adults. The majority of serious AEs was reported for orlistat (37%) and rimonabant (22%). The largest share of serious AEs was of the type 'cardiac disorders’ (19%) and ‘psychiatric disorders’ (18%). Consumer AEs reporting differed from other sources with respect to share and seriousness of AEs, type of AEs (system organ class) and medicines (ATC level 5).

Conclusions:

Many serious AEs were found for antiobesity medicines in EV, and consumers contributed with a relatively high share of reports. Although several products have been withdrawn from the market and new medicines are being marketed, the utilisation of antiobesity medicines is widespread, and therefore systematic monitoring of the safety of these medicines is necessary.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kang JG, Park CY . Anti-obesity drugs: a review about their effects and safety. Diabetes Metab J 2012; 36: 13–25.

Haddock CK, Poston WS, Dill PL, Foreyt JP, Ericsson M . Pharmacotherapy for obesity: a quantitative analysis of four decades of published randomized clinical trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002; 26: 262–273.

Glazer G . Long-term pharmacotherapy of obesity 2000: a review of efficacy and safety. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161: 1814–1824.

European Court of Justice. Case C-39/03 P Artegodan GmbH vs. The Commission. T-74/00. Available at: http://www.europa.eu (last accessed 17 April 2016).

Cheung BM, Cheung TT, Samaranayake NR . Safety of antiobesity drugs. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2013; 4: 171–181.

Greenway FL . The safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical and herbal caffeine and ephedrine use as a weight loss agent. Obes Rev 2001; 2: 199–11.

Bersani FS, Coviello M, Imperatori C, Francesconi M, Hough CM, Valeriani G et al. Adverse Psychiatric Effects Associated with Herbal Weigth-Loss Products. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 120679.

Hamp C, Kang EM, Boders-Hemphill EV . Use of prescription antiobesity drugs in the United States. Pharmacotherapy 2013; 33: 1299–1307.

Stafford RS, Radley DC . National trends in antiobesity medication use. Arch Intern Med. 2003; 12: 1046–1050.

Aagaard L, Hansen EH . Information about ADRs explored by pharmacovigilance approaches: a qualitative review of studies on antibiotics, SSRIs and NSAIDs. BMC Clin Pharmacol 2009; 9: 4.

Ali AK . Cardiovascular and congenital safety evaluation of antiobesity agents, including topiramate: a pharmacovigilance analysis of the adverse event reporting system. Value Health 2012; 15: A508.

Bray GA . Use and abuse of appetite-suppressant drugs in the treatment of obesity. Ann Intern Med 1993; 119: 707–713.

Srishanmuganathan J, Patel H, Car J, Majeed A . National trends in the use and costs of anti-obesity medications in England 1998–2005. J Public Health 2007; 29: 199–202.

Viner RM, Hsia Y, Neubert A, Wong IC . Rise in antiobesity drug prescribing for children and adolescents in the UK: a population-based study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009; 68: 844–851.

Directive 2012/26/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 amending Directive 2001/83/EC as regards pharmacovigilance. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2012:299:0001:0004:EN:PDF (last accessed 18 April 2016).

European Medicines Agency. Note for guidance—EudraVigilance Human—Processing of safety messages and individual case safety reports (ICRS). EMA/H/20665/04/Final Rev 2. Available at: http://eudravigilance.ema.eu/human/euPoliciesANDDocs03asp (last accessed 17 April 2016).

EU directive of the European Parliament and of the council amending Directive 2001/83/EC as regards information to the general public on medicinal product subjects to medical prescriptions. COM (2012) 48 final. Brussels. 10.2.2012. Available at: http://eur-lexeuropa.edu/index.htm (last accessed 17 April 2016).

Volume 9. Pharmacovigilance: medicinal products for human use and veterinary products. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/pharmaceuticals/eudralex/home9.htm (last accessed 17 April 2016).

Borg JJ, Aislaitner G, Pirozynski M, Mifsud S . Strengthening and rationalizing pharmacovigilance in the EU: where is Europe heading to? A review of the new EU legislation on pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf 2011; 34: 187–197.

MedDRA. Available at: http://www.meddra.org (last accessed 18 April 2016).

R Core team A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. Available at https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/3.0.1/ Last update 2013-05-16 (last accessed 02 June 2013).

Regulation (EC) No. 1049/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2001 regarding public access to European Parliament, Council and Commission documents. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/PDF/r1049_en.pdf (last accessed 18 April 2016).

McNaughton R, Huet G, Shakir S . An investigation into drug products withdrawn from the EU market between 2002 and 2011 for safety reasons and the evidence used to support the decision-making. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004221.

Bosello O, Carruba MO, Ferrannini E, Rotella CM . Sibutramine lost and found. Eat Weight Disord 2002; 7: 161–167.

Haslam D . Weight management in obesity—past and present. Int J Clin Pract 2016; 70: 206–217.

Khan SA, Spiegel DA, Jobe PC . Psychomimetic effects of anorectic drugs. Am Fam Physician 1987; 36: 107–112.

Aagaard L, Strandell J, Melskens L, Petersen PS, Hansen EH . Global patterns of adverse drug reactions over a decade: analyses of reports to VigiBaseTM. Drug Saf 2012; 35: 1171–1182.

James WP . The epidemiology of obesity: the size problem. J Intern Med 2008; 263: 336–352.

Blenkinsopp A, Wilkie P, Wang M, Routledge PA . Patient reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions: a review of published literature and international experience. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 63: 148–156.

Van Hunsel F, Talsma A, van Puijenbroek E, de Jong-van den Berg L, van Grootheest K . The proportion of patient reports of suspected ADRs to signal detection in the Netherlands: case–control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011; 20: 286–291.

Aagaard L, Nielsen LH, Hansen EH . Consumer reporting of adverse drug reactions. A retrospective analysis of Danish Adverse Drug Reaction Database from 2004 to 2006. Drug Saf 2009; 32: 1067–1074.

Van Grootheest AC, Passier JL, van Puijenbroek EP . Direct reporting of side effects by the patient: favourable experience in the first year [in dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005; 149: 529–533.

De Langen J, van Hunsel F, Passier A, de Jong-van den Berg L, van Grootheest K . Adverse drug reactions reporting by patients in the Netherlands: three years of experience. Drug Saf 2008; 31: 515–524.

Herxheimer A, Mintzes B . Antidepressants and adverse effects in young patients: uncovering the experience. CMAJ 2004; 170: 486–489.

Medawar C, Herxheimer A . A comparison of adverse drug reaction reports from professionals and users relating to risk of dependence and suicidal behaviour with paroxetine. Int J Risk Saf Med 2003; 16: 5–19.

Egberts TC, Smulders M, de Konig FH, Meyboom RH, Leufkens HG . Can adverse drug reactions be detected earlier? A comparison of reports by patients and heath care professionals? BMJ 1996; 313: 530–531.

Mitchell AS, Henry DA, Sanson-Fischer R, O’Donnell DL . Patient as direct source for information on adverse drug reactions. BMJ 1988; 297: 891–893.

Bongard V, Menard-Tache S, Bagheri H, Kabiri K . Perception of the risk of adverse drug reactions: differences between other reporters and non other reporters. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2002; 54: 433–436.

Härmark L, van Hunsel F, Grundmark B . ADR reporting by the general public: lessons learnt from the Dutch and Swedish Systems. Drug Saf 2015; 38: 337–347.

Ahmad SR . Comment on: ‘Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting by Patients: an overview of Fifty Countries’. Drug Saf 2015; 38: 109–110.

Benkirane R, Soulaymani-Becheikh R, Khattabi A, Benabdallah G, Alj L, Sefiani H et al. Assessment of a new instrument for detecting preventable adverse drug reactions. Drug Saf 2015; 38: 383–393.

European Medicines Agency. Risk Management for Medicinal Products in the EU: European Medicines agency. Available at: https://eudravigilance.ema.europa.eu/human/evRiskManagement.asp (last accessed 02 June 2016).

Pal SN, Olsson S, Brown EG . The monitoring medicines project: a multinational pharmacovigilance and public health project. Drug Saf 2015; 38: 319–328.

Fouretier A, Malriq D, Bertram D . Open Access Pharmacovigilance databases: analysis of 11 databases. Pharm Med 2016; 30: 221–231.

Acknowledgements

We thank the European Medicines Agency for providing access to data (EMA/712166/2014).

Author contributions

EHH, LA, CEH conceived and designed the study; CEH, LA and EHH performed the experiments and LA, CEH and EHH analysed the data and wrote the final paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aagaard, L., Hallgreen, C. & Hansen, E. Serious adverse events reported for antiobesity medicines: postmarketing experiences from the EU adverse event reporting system EudraVigilance. Int J Obes 40, 1742–1747 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.135

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.135

This article is cited by

-

Descriptive analysis of reported adverse events associated with anti-obesity medications using FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) databases 2013–2020

International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy (2022)

-

Molecular and neurocircuitry mechanisms of social avoidance

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2021)

-

Post-marketing withdrawal of anti-obesity medicinal products because of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review

BMC Medicine (2016)