Abstract

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a group of inherited connective tissue disorders characterized by hyperextensible skin, joint hypermobility and soft tissue fragility. For molecular diagnosis, targeted exome sequencing was performed on a 9-year-old male patient who was clinically suspected to have EDS. The patient presented with progressive kyphoscoliosis, joint hypermobility and hyperextensible skin without scars. Ultimately, classical EDS was diagnosed by identifying a novel, mono-allelic mutation in COL5A2 [NM_000393.3(COL5A2_v001):c.682G>A, p.Gly228Arg].

Similar content being viewed by others

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a heritable connective tissue disorder characterized by a varying degree of skin hyperextensibility, joint hypermobility and generalized connective tissue fragility.1 According to the Villefranche nosology, there are six subtypes of EDS that are classified on the basis of their clinical, biochemical and molecular characteristics: classical, hypermobile, vascular, kyphoscoliosis, arthrochalasia and dermatosparaxis.2 Accurate EDS diagnosis allows for appropriate screening of life-altering complications, including vascular and hollow organ rupture, and ligamentous laxity, leading to chronic dislocation with subsequent pain and long-term disability.3 The various forms of EDS are diagnosed on the basis of the patient’s clinical presentation and family history. However, because of overlapping symptoms, diagnosing EDS remains a challenge, and many patients are left undiagnosed or have a delayed diagnosis. These cases may remain uncategorized, even by well-trained medical professionals.4,5

Mutations in genes encoding fibrillar (type I, III and V) collagen chains or proteins have been identified in most types of EDS, with the exception of the hypermobility type. These known underlying genetic defects are different in each subtype.5 Genetic testing may be diagnostically useful to identify specific EDS subtypes, but even in typical cases, genetic defects are not always detected in disease-causing genes.5–7 Because of shared clinical features between EDS subtypes, the diagnosis of these rare conditions is difficult, and an accurate diagnosis using the appropriate genetic test for each subtype can be challenging. For a molecular diagnosis outside the expected EDS genotype–phenotype relationship, simultaneous testing for multiple potential disease-causing genes in the suspected EDS patient may be an effective and systematic approach. Conventional Sanger sequencing has routinely been used for genetic testing to identify disease-causing mutations; however, it is laborious, expensive and time consuming for multiple candidate genes.8 Recently, targeted exome sequencing (TES) of candidate or known disease-associated genes utilizing next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has been used to diagnose patients with various types of disorders, including EDS.8 Here we report a de novo mono-allelic missense mutation of COL5A2 (MIM 120190), NM_000393.3(COL5A2_v001):c.682G>A, detected in a TES panel for the coding regions of 4,813 clinical phenotype-associated genes, including EDS-associated genes, in a Japanese patient with EDS. Through this approach, the patient was diagnosed with classical EDS (cEDS).

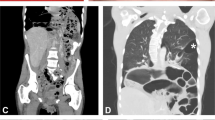

The patient is the fifth child of healthy, non-consanguineous parents. After an uneventful pregnancy, he was born at 35 weeks gestation following the premature rupture of the fetal membranes. His birth weight was 1,924 g (−1.3 SD). Because of an unknown cause, perforation of the terminal ileum occurred at the age of 2 days, and an ileostomy was performed. After follow-up with central venous nutrition and tube feeding, closure of the ileostomy was performed at the age of 52 days, and he left the hospital at the age of 73 days. He achieved head control at the age of 9 months and walked independently at the age of 18 months. At the age of 1 year, the patient was diagnosed with hypotonia and kyphoscoliosis, and treated with a brace at another clinic. His kyphoscoliosis was non-responsive to the brace and increased in severity over time. At the age of 9 years, the patient was suspected to have a connective tissue disorder because he showed muscle weakness and joint hypermobility. Therefore, he was readmitted to our hospital for diagnosis. Clinical examination at the age of 9 years showed a boy with a height of 117.4 cm (–2.3 SD) and weight of 19.9 kg (–1.5 SD). He had joint hypermobility (Beighton score=6), mild hyperextensible skin (~1.5 cm on the volar surface of the forearm) and severe kyphoscoliosis (Figure 1), but did not have widened atrophic scars. In the minor diagnostic criteria for cEDS, smooth velvety skin, muscle hypotonia and delayed gross motor development were observed in addition to the manifestations of tissue extensibility and fragility (perforation of the terminal ileum at the age of 2 days). No abnormality was revealed during physical examination of the chest and abdomen or during an ophthalmological evaluation. Echocardiography and abdominal ultrasound were normal. No family history of EDS was observed. On the basis of his clinical presentation, the patient was suspected of having cEDS (MIM 130000), kyphoscoliotic EDS (MIM 225400) or other related minor EDS types in which severe progressive kyphoscoliosis is prominent.2,5,7

Molecular diagnosis was performed on genomic DNA extracted from a blood sample after informed consent was obtained from the parents. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Tokushima University. To screen multiple EDS genes and other known disease-associated genes, we first performed TES for the proband by using a TruSight One Sequencing Panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and MiSeq benchtop sequencer (Illumina) with our pipeline for NGS data analysis, as described previously.9,10 To identify presumably pathogenic single-nucleotide variants, we excluded minor sequence variants with relatively high-allele frequencies, i.e., >0.01, included in the 1000 Genomes Project database (http://www.1000genomes.org/), NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP6500, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), Human Genetic Variation Database11 (HGVD, http://www.genome.med.kyoto-u.ac.jp/SnpDB/) and Integrative Japanese Genome Variation Database12 (iJGVD, https://ijgvd.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/). The detection of copy-number variations using TES data with a resolution of a single exon to several exons, depending on the exon size, was performed as described previously.13 These analyses identified a mono-allelic, missense mutation, NM_000393.3(COL5A2_v001):c.682G>A, in exon 9 of COL5A2, which resulted in a Gly to Arg substitution at codon 228 [NM_000393.3(COL5A2_i001):p.(Gly228Arg)]. This result was confirmed by using Sanger sequencing and was not found in the parents (Figure 2a). Primer sequences are available upon request. This mutation is not present in human genome variation databases, such as dbSNP138, 1000 Genomes Project, ESP6500, HGVD and iJGVD, or in disease-causing mutation databases, such as the Human Gene Mutation Database Professional 2016.1 (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.org/), Leiden Open Variation Database (LOVD, https://eds.gene.le.ac.uk/home.php?select_db=COL5A2) and ClinVar (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). No other potentially pathogenic single-nucleotide variants or CNAs were detected in the genes possibly responsible for EDS or other related diseases. Through in silico analysis using LJB23 databases for non-synonymous variant annotation in ANNOVAR (http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/), this mutation was predicted to damage protein function, i.e., SIFT score=0, PolyPhen-2 score=1 and MutationTaster score=1. The presence of Gly at every third residue (Gly-X-Y) is considered to be essential for the formation of the characteristic collagen triple helix (Figure 2b). Furthermore, Arg is one of the destabilizing residues observed in the Gly position of the Gly-X-Y repeating pattern in the collagen triple helix, and its presence may cause a range of heritable connective tissue disorders.14 In the HGMD 2016.1 and LOVD databases, the replacement of one Gly in the (Gly-X-Y)n repeat by Arg was reported in four out of five (80%) and five out of seven (71%) COL5A2 missense mutation cases with EDS, respectively. The results of the molecular diagnosis suggested that this is a de novo mutation responsible for EDS, and the patient was diagnosed with de novo cEDS.

(a) Electropherogram of COL5A2 (NM_000393.3) exon 9 and intron 9 sequences in the DNA of the patient and his parents. The arrowhead denotes the position of the mutated base (NM_000393.3:c.682G>A) in the patient. The DNA and corresponding amino acid sequences of the wild type and mutant COL5A2 alleles are also shown. (b) Alignment of the COL5A2 amino acid sequence around codon 228 in different mammalian species. The arrowhead denotes the position of the p.Gly228Arg mutation. The dots indicate the conserved Gly of the (Gly-X-Y)n repeat in the collagen triple helix. The amino acids that are not matched with those in Homo sapiens are depicted in light gray.

In cEDS, more than 100 distinct COL5A1 mutations have been described, but only 19 and 24 COL5A2 distinct mutations are reported in the HGMD professional 2016.1 and LOVD databases, respectively. Although COL5A1 mutations are scattered throughout the gene, most COL5A2 mutations are located within the triple-helix domain.7,15 Defects in COL5A1 are most commonly null mutations consisting of either nonsense, frameshift or splice-site mutations that generate a premature termination codon (PTC). These PTCs encode transcripts that cause rapid degradation through nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and consequently reduce production of type V collagen7,15 In contrast, nearly all of the COL5A2 mutations reported to date represent structural mutations, including missense or in-frame exon-skipping splice mutations, thus resulting in the production of mutant α2(V)-chains that probably incorporate into collagen molecules and interfere with the formation of heterotrimers.7,15 Secreted mutant heterotrimers are predicted to exert a dominant negative effect that causes functional haploinsufficiency. Because no heterozygous COL5A2 null-allele mutations have been reported, it is possible that COL5A2 null-allele mutations result in no clinical phenotype of cEDS.7 Although similar observations were reported in COL1A2 and COL11A1 in other connective tissue disorders,16,17 the sample size of COL5A2 mutations needs to be increased to conclude this hypothesis.

No clear genotype–phenotype correlations for type V collagen defects have emerged in patients with cEDS.16 The large inter- and intrafamilial phenotypic variabilities in cEDS and the possibility of the presence of a COL5A1 null allele in individuals with only minor symptoms of cEDS are also known.18 It has been reported that 20% of patients with cEDS who fulfilled all three criteria presented with severe progressive kyphoscoliosis, whereas none of the patients who fulfilled only two criteria presented with this phenotype.7 Here, however, the patient fulfilled only two major criteria of the Villefranche nosology and showed progressive kyphoscoliosis. Compared with COL5A1 mutation carriers, COL5A2 mutation carriers have been reported to fall within the more severe end of the phenotypic spectrum of cEDS, although no difference in severity has been noted in patients carrying a null mutation in one COL5A1 allele compared with patients carrying a structural mutation in COL5A1 or COL5A2.18–20 Studies involving an increased number of patients with COL5A2 mutations are needed to clarify the genotype–phenotype correlations for type V collagen defects in patients with cEDS.

HGV Database

The relevant data from this Data Report are hosted at the Human Genome Variation Database at http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.hgv.848 (2016).

References

References

Steinmann B, Royce P, Superti-Furga A. The Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. In: Royce P, Steinmann B (eds). Connective Tissue and its Heritable Disorders. Wiley-Liss: New York, 2002, pp431–523.

Beighton P, De Paepe A, Steinmann B, Tsipouras P, Wenstrup RJ. Ehlers–Danlos syndromes: revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. Ehlers–Danlos National Foundation (USA) and Ehlers-Danlos Support Group (UK). Am J Med Genet 1998; 77: 31–37.

Karaa A, Stoler JM. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: an unusual presentation you need to know about. Case Rep Pediatr 2013; 2013: 764659.

Callewaert B, Malfait F, Loeys B, De Paepe A. Ehlers–Danlos syndromes and Marfan syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2008; 22: 165–189.

Shirley ED, Demaio M, Bodurtha J. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome in orthopaedics: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment implications. Sports Health 2012; 4: 394–403.

Sobey G. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: how to diagnose and when to perform genetic tests. Arch Dis Child 2015; 100: 57–61.

Symoens S, Syx D, Malfait F, Callewaert B, De Backer J, Vanakker O et al. Comprehensive molecular analysis demonstrates type V collagen mutations in over 90% of patients with classic EDS and allows to refine diagnostic criteria. Hum Mutat 2012; 33: 1485–1493.

Weerakkody RA, Vandrovcova J, Kanonidou C, Mueller M, Gampawar P, Ibrahim Y et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing makes new molecular diagnoses and expands genotype-phenotype relationship in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Genet Med (e-pub ahead of print 24 March 2016; doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.14).

Okamoto N, Naruto T, Kohmoto T, Komori T, Imoto I. A novel PTCH1 mutation in a patient with Gorlin syndrome. Hum Genome Var 2014; 1: 14022.

Naruto T, Okamoto N, Masuda K, Endo T, Hatsukawa Y, Kohmoto T et al. Deep intronic GPR143 mutation in a Japanese family with ocular albinism. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 11334.

Higasa K, Miyake N, Yoshimura J, Okamura K, Niihori T, Saitsu H et al. Human genetic variation database, a reference database of genetic variations in the Japanese population. J Hum Genet 2016; 61: 547–553.

Yamaguchi-Kabata Y, Nariai N, Kawai Y, Sato Y, Kojima K, Tateno M et al. iJGVD: an integrative Japanese genome variation database based on whole-genome sequencing. Hum Genome Var 2015; 2: 15050.

Morita K, Naruto T, Tanimoto K, Yasukawa C, Oikawa Y, Masuda K et al. Simultaneous detection of both single nucleotide variations and copy number alterations by next-generation sequencing in Gorlin syndrome. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0140480.

Persikov AV, Pillitteri RJ, Amin P, Schwarze U, Byers PH, Brodsky B. Stability related bias in residues replacing glycines within the collagen triple helix (Gly-Xaa-Yaa) in inherited connective tissue disorders. Hum Mutat 2004; 24: 330–337.

Ritelli M, Dordoni C, Venturini M, Chiarelli N, Quinzani S, Traversa M et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of 40 patients with classic Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: identification of 18 COL5A1 and 2 COL5A2 novel mutations. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013; 8: 58.

Marini JC, Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, San Antonio JD, Milgrom S et al. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum Mutat 2007; 28: 209–221.

Steinmann B, Royce P, Superti-Furga A. Chondrodysplasias: general concepts and diagnostic and management considerations. In: Royce P, Steinmann B (eds). Connective Tissue and its Heritable Disorders. Wiley-Liss: New York, 2002, pp901–908.

Malfait F, Wenstrup RJ, De Paepe A. Clinical and genetic aspects of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, classic type. Genet Med 2010; 12: 597–605.

Malfait F, Coucke P, Symoens S, Loeys B, Nuytinck L, De Paepe A. The molecular basis of classic Ehlers–Danlos syndrome: a comprehensive study of biochemical and molecular findings in 48 unrelated patients. Hum Mutat 2005; 25: 28–37.

Richards AJ, Martin S, Nicholls AC, Harrison JB, Pope FM, Burrows NP. A single base mutation in COL5A2 causes Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type II. J Med Genet 1998; 35: 846–848.

Data Citations

Imoto, Issei HGV Database (2016) http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.hgv.848

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient and his family for participation in this study. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, grant numbers 26293304 (I.I.) and 15K19620 (T.N.), from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, M., Nakagawa, R., Naruto, T. et al. A novel missense mutation of COL5A2 in a patient with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Hum Genome Var 3, 16030 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/hgv.2016.30

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hgv.2016.30

This article is cited by

-

Investigating the effects of chronic perinatal alcohol and combined nicotine and alcohol exposure on dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurons in the VTA

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Functionally confirmed compound heterozygous ADAM17 missense loss-of-function variants cause neonatal inflammatory skin and bowel disease 1

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Classic Ehlers–Dalnos syndrome presenting as atypical chronic haematoma: a case report with novel frameshift mutation in COL5A1

BMC Pediatrics (2020)

-

Molecular diagnosis of an infant with TSC2/PKD1 contiguous gene syndrome

Human Genome Variation (2020)

-

Novel compound heterozygous CDH23 variants in a patient with Usher syndrome type I

Human Genome Variation (2019)