Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the retinal structural changes in endophthalmitis and their association with visual outcome.

Patients and methods

Forty-five eyes of 45 patients diagnosed with endophthalmitis were included. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) was performed after inflammation was controlled. The relationship between SD-OCT features and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at the last follow-up was analyzed.

Results

The structural changes included inner segment ellipsoid (ISe) disruption (49%), atrophy of retinal inner layers (24%), epimacular membrane (24%), and macular edema (24%). BCVA was worse in patients with ISe disruption (P=0.005) and retinal inner layers' atrophy (P=0.004) compared with those without. There was no significant difference of BCVA between the patients with and without epimacular membrane, or intraretinal cysts. Multivariate regression showed that atrophy of retinal inner layers (b=0.41±0.17, P=0.022) was the only independent factor associated with BCVA.

Conclusion

Atrophy of retinal inner layers is associated with visual impairment in endophthalmitis, despite successful management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endophthalmitis is a severe, sight-threatening disease that is characterized by intraocular inflammation caused by infection. Its sources can be open globe trauma, intraocular surgery, keratitis, or endogenous.1 The reported incidence of endophthalmitis is 2.1% after open globe injury,2 0.06~0.2% after cataract surgery,3 0.039% after vitrectomy,4 and 0.049% after intravitreal injection.5 Although endophthalmitis can be adequately managed with intravitreal injection of antibiotics and/or pars plana vitrectomy, impairment of vision has been observed in some patients.6 This could be due to damage of the retinal structure.

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) allows visualization of the cross-sectional structure of retina in vivo.7 It is now widely being used to investigate the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of many diseases such as retinal vein occlusion,8 age-related macular degeneration,9 glaucoma,10 central serous chorioretinopathy,11 and diabetic retinopathy.12 SD-OCT has also been used to investigate the structural changes in endophthalmitis.13, 14, 15 However, these studies only focused on postoperative source of endophthalmitis. Furthermore, none of these studies analyzed the relationship between retinal structural changes and visual function.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the structural changes in the retina after successful management of endophthalmitis, and their association with visual function.

Materials and methods

Subjects

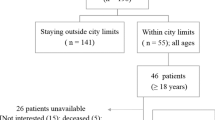

This is a retrospective study. The Institutional Review Board of Joint Shantou International Eye Center of Shantou University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong approved the study protocol. Informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study. The records of all patients diagnosed with endophthalmitis between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2016 at the Joint Shantou International Eye Center of Shantou University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong were reviewed. Patients who met the following criteria were included: (1) diagnosed with endophthalmitis; (2) underwent an OCT examination after control of inflammation; and (3) followed up for at least 3 months. Patients with any following criteria were excluded: (1) history of retinal detachment, age-related macular degeneration, retinal vein occlusion, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, or any other retinopathy; (2) poor quality of OCT images; (3) coexisting pathology at macula other than endophthalmitis, such as intraocular foreign body at macula, macular hole, or retinal detachment; (4) corneal wound within 3 mm diameter of corneal center; and (5) clinically significant cataract that affected visual acuity.

Optical coherence tomography

SD-OCT was performed with Cirrus High Definition OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA) or Topcon 3D OCT-1000 (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Both machines are a type of SD-OCT. The scanning protocol included 64 × 512 scans, which produced retinal thickness map and high-definition raster or five lines scan. The images from both scans were used to assess the structure of retina.

OCT images taken more than 3 months after control of endophthalmitis were reviewed by a retinal specialist who was masked to the visual acuity of patients. Four kinds of structural characters were assessed. The OCT images were manually segmented to inner and outer retina at the border of the outer plexiform and outer nuclear layers. Atrophy of the retinal inner layers was defined as a reduced thickness of retinal inner layers and absence of boundary between retinal inner layers (Figure 1). Inner segment ellipsoid (ISe) band disruption was defined as loss and irregularity of the hyper-reflective line corresponding to the ISe band (Figures 2a and b). Epimacular membrane was defined as a continuous hyper-reflective line attached to the retinal inner surface (Figures 2c and d). Intraretinal cyst was defined as the minimally reflective space within the neurosensory retina (Figures 2e and f).

Optical coherence tomography of two patients with retinal inner atrophy after endophthalmitis. (a). The cross-section vertical B scan showed reduced retinal inner layers’ thickness and absence of a boundary between these layers (arrow). The hyper-reflective lines are reflection from silicone oil. (b) The corresponding retinal thickness map showing reduced retinal thickness at inferior and temporal retina. (c) The cross-section horizontal B scan showed reduced retinal inner layers’ thickness and absence of a boundary between these layers (arrow). (d) The corresponding retinal thickness map showing reduced retinal thickness at temporal retina. The green lines in a and c were the manual segmentation of the border between outer plexiform layer and outer nuclear layer. The figure suggests that the thinning was mostly due to atrophy of inner retina but not outer retina. The red cross in b and d indicates fovea. The figure demonstrates that retinal thinning involved fovea.

Visual acuity

Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was measured with the Chinese standard logarithm visual chart and then converted into Logarithm of minimal angle of resolution (LogMAR) unit. Finger count was converted to 2.0 LogMAR and hand movements were converted to 2.3 LogMAR.16 The measurement of BCVA at the last follow-up was used as functional outcome.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with commercially available software (SPSS ver. 17.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution of variants was assessed using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The results were presented as the median. Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare BCVA in patients with and without retinal structural changes. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to investigate the correlation between BCVA and anatomical characteristics of the retina. The tests were two-sided. The level of significance was set as P-value less than 0.05.

Results

Forty-five eyes from 45 patients (12 females, 33 males) were included in this study. The age of patients ranged from 4 to 87 years (median age 45 years). The sources of endophthalmitis were open globe injury in 34 eyes, cataract surgery in 8 eyes, and endogenous in 3 eyes. Thirty-eight eyes were treated with pars plana vitrectomy combined with intravitreal injection of antibiotics or vitreous cavity lavage of antibiotics. The other seven eyes received intraocular injection of antibiotics only. The LogMAR BCVA at final visit ranged from 0.0 to 2.3, with the median of 0.52. The demographics and clinical characteristics of each patient were presented in Table 1.

On SD-OCT images taken more than 3 months after control of endophthalmitis, atrophy of the retinal inner layers was detected in 11 (24%) eyes, ISe band disruption was identified in 22 (49%) eyes, epimacular membrane was found in 11 (24%) eyes, and intraretinal cysts presented in 11 (24%) eyes. The prevalence of these structural changes in each type of endophthalmitis was listed in Table 2.

LogMAR BCVA was worse in the eyes with atrophy of retinal inner layers compared to those without (median 0.90 vs 0.40 LogMAR, P=0.002, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 3a). BCVA was also worse in patients with ISe disruption than in those without ISe disruption (median 0.70 vs 0.30 LogMAR, P=0.004, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 3b). There was no significant difference of BCVA between patients with and without epimacular membrane, or between patients with and without intraretinal cysts (both P>0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figures 3c and d). Multivariable linear regression analysis showed that atrophy of retinal inner layers (b=0.41±0.17, P=0.022) was the only independent factor strongly associated with visual outcome.

Box charts for comparison of best-corrected visual acuity in endophthalmitis patients with and without morphological changes. The P-values were calculated from Mann–Whitney U-test. (a) Retinal inner layers' atrophy. (b) Inner segment ellipsoid band disruption. (c) Epimacular membrane. (d) Intraretinal cyst.

Discussion

Our study observed retinal structural changes including atrophy of the retinal inner layers, ISe disruption, epimacular membrane, and intraretinal cysts in endophthalmitis after successful management. The visual acuities were significantly reduced in patients with ISe disruption or atrophy of retinal inner layers. After adjusting for covariates, atrophy of retinal inner layers was the only independent factor associated with visual acuity impairment.

A few previous studies have reported retinal atrophy after endophthalmitis.15, 17 Singh et al17 reported 5 of 20 eyes with neurosensory retinal atrophy and two of them with macular ischemia on fluorescein angiography. However, their report was limited by the low resolution of time domain OCT, which could not differentiate between inner or outer retinal atrophy. Bjerrum et al15 reported that retinal atrophy located temporal to the fovea in 13 of 42 postoperative endophthalmitis eyes. They found that massive atrophy was mostly due to loss of nerve fibers and ganglion cells. Zinkernagel et al14 found ganglion cell complex thinning in seven of nine patients with endophthalmitis after cataract extraction surgery. There were also studies that reported no significant change of retinal thickness in endophthalmitis eyes compared to control.13, 14 The inconsistency of changes in retinal thickness associated with endophthalmitis may be due to variations in study sample sizes and severities of disease. In addition to thinning of retinal inner layers, we have also observed that the boundary of retinal inner layers was indistinguishable in endophthalmitis eyes. Furthermore, multivariate regression analysis showed that retinal inner atrophy was the only independent factor associated with poor visual outcome.

Retinal inner layers were supplied by the retinal vasculature. Atrophy of retinal inner layers is also seen in other retinal ischemic diseases including central18 or branch19 retinal artery occlusion, diabetic retinopathy,20, 21, 22, 23, 24 and retinal vein occlusion.25 Animal model of Bacillus endophthalmitis revealed that retinal vasculature was occluded by infiltrating inflammatory cells, mostly polymorphonuclear leukocytes.26, 27 Clinically, retinal vasculitis or periphlebitis has been directly visualized by biomicroscopy or by the operating microscope during surgery in eyes with endophthalmitis.28, 29 Figure 4 showed a case of traumatic endophthalmitis in which retinal vasculitis was observed during vitrectomy. Early postoperative SD-OCT showed high optical intensity in the retinal inner layers, and late-stage SD-OCT-identified atrophy of retinal inner layers. Previously, we have observed increased optical intensity in retinal inner layers during the acute phase of central retinal artery occlusion, which could be a potential biomarker for retinal ischemia.30, 31 Similarly, the increased optical intensity of inner retinal layers in endophthalmitis eyes suggests that inflammation of retinal vessel results in vascular occlusion, subsequently leading to retinal ischemia, and finally atrophy occurs in the retinal inner layers causing irreversible visual impairment.

A case with traumatic endophthalmitis. (a, b) Retinal vasculitis was found during operation. (c) Partial resolution of retinal vasculitis 4 days after vitrectomy. (d) Complete resolution of retinal vasculitis 6 months after vitrectomy. (e) Increased optical intensity in inner layers (white arrow) on optical coherence tomography 4 days after vitrectomy. (f) Atrophy of retinal inner layers (yellow arrow) on optical coherence tomography 6 months after vitrectomy.

ISe disruption has been reported after endophthalmitis in previous studies14, 32 and was noted in 49% of the eyes in our cohort. The presence of ISe disruption was associated with worse visual acuity. ISe disruption indicates photoreceptor damage.33 In experimental endophthalmitis, the inoculation of bacterial infection and its toxic byproducts had caused direct damage to photoreceptors.26 Epimacular membrane and intraretinal cysts had been reported as morphological changes after endophthalmitis.14, 15, 17, 32 However, these morphological changes were not associated with visual impairment in our case series.

The pathogenesis leading to the morphological changes in endophthalmitis remains unclear. They may be directly related to the virulence of the infectious microorganism, due to secondary immune responses, or due to the toxicity of antibiotics. Some cases in our study were secondary to open globe injury. The mechanisms of ISe disruption, epimacular membrane, or intraretinal cysts may be secondary to trauma. However, we postulate that atrophy of retinal inner layers is related to endophthalmitis because it has not occurred in open globe injury. There were studies that reported rare cases of macular atrophy associated with the use of intravitreal amikacin.34, 35, 36 However, our study used ceftazidime or vancomycin and did not use amikacin. Retinal toxicity is less likely to occur without repetitive intravitreal antibiotics injections.37 Oum et al37 did not find retinal toxicity in eyes that received single injection of antibiotics. Nevertheless, our study is a clinical study that focuses on the morphological changes by in vivo imaging. Further studies are needed to investigate the molecular pathogenesis of these changes.

We recognize a number of limitations in this study. First, there are different causes of endophthalmitis, and the number of patients is not large enough to allow us to compare the visual and structural alteration between different subgroups. Second, we only compared the presence and absence of structural changes. Further study is needed to quantify the severity and location of structural changes and further investigate the structure–function correlation. Third, we only have one time point in most cases and hence cannot investigate the longitudinal changes of retinal structure. Further study is required to investigate the role of OCT at an early stage of endophthalmitis. Fourth, this is a retrospective study, and we do not have the OCT images of the contralateral eye and, therefore, cannot make the comparison between the eye affected by endophthalmitis and the fellow eye. The unusually high frequencies of 24 and 48% suggested that these tomographic changes were unlikely incidental findings.

In conclusion, we found that even after successful treatment of endophthalmitis, there are retinal structural changes such as ISe disruption, atrophy of retinal inner layer, epimacular membrane, and macular edema. Among them, retinal inner layers' atrophy was strongly associated with visual impairment in endophthalmitis.

References

Bhoomibunchoo C, Ratanapakorn T, Sinawat S, Sanguansak T, Moontawee K, Yospaiboon Y et al. Infectious endophthalmitis: review of 420 cases. Clin Ophthalmol 2013; 7: 247–252.

Dehghani AR, Rezaei L, Salam H, Mohammadi Z, Mahboubi M . Post traumatic endophthalmitis: incidence and risk factors. Glob J Health Sci 2014; 6: 68–72.

Du DT, Wagoner A, Barone SB, Zinderman CE, Kelman JA, Macurdy TE et al. Incidence of endophthalmitis after corneal transplant or cataract surgery in a medicare population. Ophthalmology 2014; 121: 290–298.

Eifrig CW, Scott IU, Flynn Jr HW, Smiddy WE, Newton J . Endophthalmitis after pars plana vitrectomy: Incidence, causative organisms, and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 138: 799–802.

McCannel CA . Meta-analysis of endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents: causative organisms and possible prevention strategies. Retina 2011; 31: 654–661.

Vaziri K, Schwartz SG, Kishor K, Flynn HW Jr . Endophthalmitis: state of the art. Clin Ophthalmol 2015; 9: 95–108.

Stopa M, Bower BA, Davies E, Izatt JA, Toth CA . Correlation of pathologic features in spectral domain optical coherence tomography with conventional retinal studies. Retina 2008; 28: 298–308.

Akagi-Kurashige Y, Tsujikawa A, Ooto S, Makiyama Y, Muraoka Y, Kumagai K et al. Retinal microstructural changes in eyes with resolved branch retinal vein occlusion: an adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy study. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 157: 1239–1249 e1233.

Schachat AP, Thompson JT . Optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography, and the management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2015; 122: 222–223.

Yoon JY, Na JK, Park CK . Detecting the progression of normal tension glaucoma: a comparison of perimetry, optic coherence tomography, and heidelberg retinal tomography. Korean J Ophthalmol 2015; 29: 31–39.

Carrai P, Pichi F, Bonsignore F, Ciardella AP, Nucci P . Wide-field spectral domain-optical coherence tomography in central serous chorioretinopathy. Int Ophthalmol 2015; 35: 167–171.

Gella L, Raman R, Rani PK, Sharma T . Spectral domain optical coherence tomography characteristics in diabetic retinopathy. Oman J Ophthalmol 2014; 7: 126–129.

Maneschg OA, Volek E, Németh J, Somfai GM, Géhl Z, Szalai I et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography in patients after successful management of postoperative endophthalmitis following cataract surgery by pars plana vitrectomy. BMC Ophthalmol 2014; 14: 76.

Zinkernagel MS, Dysli C, Wolf S, Ebneter A . Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings after severe exogenous endophthalmitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2014; 22: 439–443.

Solborg Bjerrum S, Prause JU, Fuchs J, la Cour M, Kiilgaard JF . Morphological features in eyes with endophthalmitis after cataract surgery - histopathology and optical coherence tomography assessment. Acta Ophthalmol 2016; 94: 26–30.

Lange C, Feltgen N, Junker B, Schulze-Bonsel K, Bach M . Resolving the clinical acuity categories ‘hand motion’ and ‘counting fingers’ using the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FrACT). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009; 247: 137–142.

Singh R, Gupta V, Gupta A, Dogra MR . Optical coherence tomography following successful management of endophthalmitis. Indian J Ophthalmol 2007; 55: 234–235.

Shinoda K, Yamada K, Matsumoto CS, Kimoto K, Nakatsuka K . Changes in retinal thickness are correlated with alterations of electroretinogram in eyes with central retinal artery occlusion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008; 246: 949–954.

Ritter M, Sacu S, Deák GG, Kircher K, Sayegh RG, Pruente C et al. In vivo identification of alteration of inner neurosensory layers in branch retinal artery occlusion. Br J Ophthalmol 2012; 96: 201–207.

Gibran SK, Khan K, Jungkim S, Cleary PE . Optical coherence tomographic pattern may predict visual outcome after intravitreal triamcinolone for diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 890–894.

Nicholson L, Ramu J, Triantafyllopoulou I, Patrao NV, Comyn O, Hykin P et al. Diagnostic accuracy of disorganization of the retinal inner layers in detecting macular capillary non-perfusion in diabetic retinopathy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2015; 43: 735–741.

Radwan SH, Soliman AZ, Tokarev J, Zhang L, van Kuijk FJ, Koozekanani DD et al. Association of disorganization of retinal inner layers with vision after resolution of center-involved diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015; 133: 820–825.

Sun JK, Lin MM, Lammer J, Prager S, Sarangi R, Silva PS et al. Disorganization of the retinal inner layers as a predictor of visual acuity in eyes with center-involved diabetic macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014; 132: 1309–1316.

Sun JK, Radwan SH, Soliman AZ, Lammer J, Lin MM, Prager SG et al. Neural retinal disorganization as a robust marker of visual acuity in current and resolved diabetic macular edema. Diabetes 2015; 64: 2560–2570.

Rahimy E, Sarraf D, Dollin ML, Pitcher JD, Ho AC . Paracentral acute middle maculopathy in nonischemic central retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2014; 158: 372–380 e371.

Ramadan RT, Ramirez R, Novosad BD, Callegan MC . Acute inflammation and loss of retinal architecture and function during experimental Bacillus endophthalmitis. Curr Eye Res 2006; 31: 955–965.

Ramadan R, Novosad BD, Callegan MC . Phenotypic analysis of infiltrating inflammatory cells during bacillus endophthalmitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005; 46: 1174–1174.

Relhan N, Jalali S, Nalamada S, Dave V, Mathai A . Traumatic endophthalmitis presenting as isolated retinal vasculitis and white-centered hemorrhages: case report and review of literature. Indian J Ophthalmol 2012; 60: 317–319.

Ji Y, Jiang C, Ji J, Luo Y, Jiang Y, Lu Y et al. Post-cataract endophthalmitis caused by multidrug-resistant Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: clinical features and risk factors. BMC Ophthalmol 2015; 15: 14.

Chen H, Xia H, Qiu Z, Chen W, Chen X . Correlation of optical intensity on optical coherence tomography and visual outcome in central retinal artery occlusion. Retina 2016; 36: 1964–1970.

Chen H, Chen X, Qiu Z, Xiang D, Chen W, Shi F et al. Quantitative analysis of retinal layers' optical intensities on 3D optical coherence tomography for central retinal artery occlusion. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 9269.

Zhou T, Aptel F, Bron AM, Cornut PL, Palombi K, Thuret G et al. Longitudinal study of retinal status using optical coherence tomography after acute onset endophthalmitis following cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2017; e-pub ahead of print 24 January 2017; doi: doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309542.

Saxena S, Srivastav K, Cheung CM, Ng JY, Lai TY . Photoreceptor inner segment ellipsoid band integrity on spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Clin Ophthalmol 2014; 8: 2507–2522.

Widmer S, Helbig H . Presumed macular toxicity of intravitreal antibiotics. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd 2006; 223: 456–458.

Seawright AA, Bourke RD, Cooling RJ . Macula toxicity after intravitreal amikacin. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1996; 24: 143–146.

Yeo DC, Zhao D, Smith M, Al-bermani A . Optical coherence tomography and fundus fluorescein angiography of a case of macular toxicity from intravitreal amikacin. BMJ Case Rep 2016; e-pub ahead of print 26 February 2016; doi: doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-214614.

Oum BS, D'Amico DJ, Kwak HW, Wong KW . Intravitreal antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and aminoglycoside: examination of the retinal toxicity of repetitive injections after vitreous and lens surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1992; 230: 56–61.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (81170853) and Joint Shantou International Eye Center Intramural Grant (2010-025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, X., Chen, W., Xia, H. et al. Atrophy of retinal inner layers is associated with poor vision after endophthalmitis: a spectral domain optical coherence tomography study. Eye 31, 1488–1495 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.100

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.100

This article is cited by

-

Visual function deficits in eyes with resolved endophthalmitis

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Prognostic factors associated with visual outcome of salvageable eyes with posttraumatic endophthalmitis

Scientific Reports (2019)