Abstract

Personalized medicine promises that an individual’s genetic information will be increasingly used to prioritize access to health care. Use of genetic information to inform medical decision making, however, raises questions as to whether such use could be inequitable. Using breast cancer genetic risk prediction models as an example, on the surface clinical use of genetic information is consistent with the tools provided by evidence-based medicine, representing a means to equitably distribute limited health-care resources. However, at present, given limitations inherent to the tools themselves, and the mechanisms surrounding their implementation, it becomes clear that reliance on an individual’s genetic information as part of medical decision making could serve as a vehicle through which disparities are perpetuated under public and private health-care delivery models. The potential for inequities arising from using genetic information to determine access to health care has been rarely discussed. Yet, it raises legal and ethical questions distinct from those raised surrounding genetic discrimination in employment or access to private insurance. Given the increasing role personalized medicine is forecast to play in the provision of health care, addressing a broader view of what constitutes genetic discrimination, one that occurs along a continuum and includes inequitable access, will be needed during the implementation of new applications based on individual genetic profiles. Only by anticipating and addressing the potential for inequitable access to health care occurring from using genetic information will we move closer to realizing the goal of personalized medicine: to improve the health of individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Using genetic information in medical decision making

Advances in biomedical research have given way to new enthusiasm surrounding the expectation that medical treatment will be informed by an individual’s genetic information.1, 2 As knowledge of the genetic factors underlying complex diseases such as cancer advances, new tools for disease risk assessment, screening, prognosis, and therapeutics incorporating this knowledge are continuing to emerge at an increasingly rapid pace.2 Tailoring medical treatment decisions to an individual’s genetic profile is thought to give rise to a host of advantages. For the individual, using their own genetic information to guide medical decisions will optimize patient care by allowing for the personalized assessment of disease risk, and prescription of treatments with higher likelihoods of success.2 For society, integrating the use of personal genetic information into health-care delivery is hoped to result in significant cost savings by administering treatments only to those most likely to benefit.3

Should the use of individual genetic information in the delivery of health care be a cause for concern? Fears regarding the potential for misuse of genetic information have given rise to the concept of ‘genetic discrimination’, directed against an individual ‘based solely on an apparent or perceived genetic variation from the normal human genotype’.4 Dialog surrounding genetic discrimination has predominately occurred in relation to use of genetic information contained in a patient’s medical file by third parties with access to the information: namely employers and private insurance companies providing disability or life insurance (see eg5, 6, 7). So prevalent is public concern over the possibility of genetic discrimination, legislation exists prohibiting it in many jurisdictions (reviewed in8). But the rise of personalized medicine raises questions as to whether the use of an individual’s genetic information to inform medical decision making by health-care professionals collecting the information could be inequitable, perhaps amounting to discrimination. By discrimination, we mean the possibility of indirect discrimination, whereby policies or practices surrounding the use of genetic information in medical decision making could have the unintended effect of denying individuals access to health care on non-medical grounds.9 We ask whether exclusion based on genetic information could result in inequitable access to health care, where equal medical need does not result in equal access. Here, we examine this question from legal and socioethical perspectives. Indeed, these questions are timely as stakeholders worldwide have acknowledged that establishing fair access to genomic medicine is a priority as they contemplate translation strategies.10, 11, 12

The practice of oncology has been revolutionized by the use of individual genetic information to identify those most at risk or likely to benefit from increased surveillance, therapeutic, and risk reduction measures for cancer.13, 14 Among the many new developments, genetic risk assessment models that calculate cancer risk represent an excellent case study from which to ask whether inequitable access to health care can result from the use of individual genetic information. Indeed, risk assessment that includes individual genetic information is one of the fastest growing areas of personalized medicine and promises to be a prominent component of health-care delivery going forward.15 Presently, clinical risk assessment for complex disease is predominantly based on family history, lifestyle, and shared environmental factors and the predictive value of non-genomic-based risk assessment is considered variable or low.16 Further, while genetic models have been in existence for nearly 20 years for breast cancer, the advent of genome-wide association scans and whole genome sequencing has led to the forecast that new risk prediction tools will emerge capable of using genomics to calculate an individual’s risk of developing not only cancer, but numerous other complex diseases.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Proposed risk assessment tools that include individual genomic information, however, promise to raise distinct concerns, as the analytic validity of such risk assessment is, arguably, higher than family history, justifying a greater number of medical decisions to be based on it.16 With a greater number of risk assessment tools with increased predictive value expected to emerge, genomic-based risk assessment promises to have a profound impact on the delivery of health care by using genetic information to identify and intervene for those at risk, prior to development of disease.

Case study: breast cancer risk prediction models

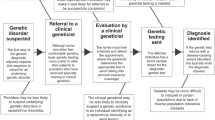

Breast cancer genetic risk assessment models are clinical tools that calculate a patients’ individual risk for developing cancer or harboring a cancer predisposing genetic mutation. These tools seek to identify patients likely to benefit from increased cancer surveillance, prophylactic treatments, and other cancer risk reducing interventions.17 In existence for nearly 20 years, the models are based on cancer prevalence in particular populations.17 By mapping individual factors from the patient such as family history of cancer, age, etc., into the models, a patients’ individual cancer risk can be expressed numerically.17 Countries worldwide have established particular risk thresholds required before a patient is eligible for additional screening, or cancer risk reduction measures.23 As a result, patient stratification regarding access to health care occurs through the use of their genetic information.

On the surface, use of breast cancer genetic risk prediction models to select patients for additional health care should not raise concerns for equitable access. Indeed, they are tools that have the purpose of improving the delivery health care. Strong medical, legal, ethical, and economic arguments exist favoring their use to maintain or improve equitable access to health care. From a medical perspective, decisions based on the best available scientific evidence is part of evidence-based medicine, a widely adopted practice in health-care systems worldwide.24, 25, 26 Hence, the use of risk assessment scores to select patients for additional care is consistent with evidence-based medicine.

Use of risk assessment scores to prioritize patients can be justified from a legal perspective in the context of a publically funded health-care system. For example, in Canada, the Canada Health Act, specifies the conditions for public funding of health care stipulating that universal public funding is provided for services that are deemed ‘medically necessary for the purpose of maintaining health, preventing disease or diagnosing or treating an injury, illness or disability’.27 Thus use of cancer risk assessment scores as a medical tool to identify those patients in need of further medical intervention is consistent with the legislated purpose of the public health insurance program to provide funding for medically necessary care.

Use of risk assessment scores can also be justified from ethical perspectives. Indeed, selecting only patients likely to benefit from additional interventions spares those unlikely to benefit from the burden of additional medical treatment, consistent with the principle of non-malfeasance.28 In publically funded health-care systems, limiting access to additional screening and testing by establishing thresholds through the use of risk assessment represents a fair distribution of limited resources, by prescribing additional treatment only to those in need.28

Limitations of risk prediction models

While use of breast cancer genetic risk prediction models has advantages, the technology has limitations. Increasingly, researchers and decision makers have come to realize that successful implementation of genomic-based technologies requires consideration of not only benefits, but also drawbacks, medical, and otherwise.29, 30 Thus, the clinical application of breast cancer genetic risk prediction models provides an opportunity to identify limitations and examine the consequences for equitable access to health care. Two categories of limitations can potentially give rise to the unintended effect of perpetuating inequities in access to health care: (i) limitations inherent to the models themselves and (ii) the means by which the models are implemented and used.

First, underlying limitations of the models themselves raise the question as to whether their use could be inequitable when applied across a general population. Indeed, variability exists within individual models in their ability to assess risk among different age and ethnic groups.31, 32, 33 Age under 40 has been shown to be a factor resulting in reduced accuracy of the models.34, 35 Moreover, ethnicity has been shown to affect validity of the resulting risk assessment. In effect, some models have a high level of accuracy among some groups, such as Italian or French Canadian populations,36, 37 while at the same time underestimating risk among other groups such as African-American, Turkish, Iranian, or Hispanic populations.31, 38, 39, 40, 41 Concerns over accuracy among African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians have led to questions from the medical community as to whether individuals in these groups receive optimal care when medical decisions are based on risk assessment scores.42

Variability also exists across models. More than a dozen models assessing breast cancer risk exist, and inconsistencies have been reported with respect to which model provides the most accurate degree of risk assessment.31, 33, 43, 44 As new data about the risk factors for cancer are continually incorporated into the models, understanding of the models becomes a moving target.17, 45 Finally, despite the clinical use of breast cancer risk prediction models for over 20 years, systematic reviews of their performance have raised questions regarding their ability to consistently and accurately predict breast cancer risk across different populations, while the need for ongoing validation of the models as they are modified has been recognized.43, 46

A second limitation relates to the implementation of the models into medical practice. Clinical collection of patient information upon which risk assessment is based is one example that illustrates the potential for inequities to occur during implementation. Family history, which provides insight into the shared genetic information of individuals, is considered the largest risk factor after age and gender for a number of cancers and other chronic conditions.47, 48 As breast cancer risk prediction models rely heavily on family history, it follows that accuracy of family history can significantly affect the validity of the resulting risk assessment.17 Despite the potential value of family history in cancer treatment and prevention, barriers have been reported in its clinical collection.47 Indeed, it is widely accepted that accuracy of family history is considered inadequate to fully assess familial cancer risk.47, 49, 50, 51 Underlying inequities are known to exist emanating from both patients and health-care professionals. From patients, knowledge, socioeconomic, and cultural barriers are each factors that have been shown to influence patient’s accuracy of their family history.52, 53, 54, 55, 56 Older age, lower education, and membership in a minority group have also been shown to be associated with lower accuracy of personal and family history of cancer.57, 58, 59

Health-care providers also contribute to the inaccuracy of family history. As no standard medical definition of family member exists, health-care providers have reported being unclear themselves regarding information that should be collected.50, 60 Further, health-care provider knowledge of cancer incidence among minority populations is purported to be a barrier to accurate collection of family history.54, 61 This has led to the recognition of the need to routinize and educate health-care professionals in clinical family history collection, and develop distinct family history tools targeting underserved groups.47, 50, 52, 53 However, at present, such tools are only in the preliminary stages of development and still require validation.47, 50, 51

Consequences for equitable access to health care

Limitations with respect to age, race, and underlying variability across breast cancer genetic risk prediction models, as well as limitations arising during their implementation, raise the possibility that some populations are excluded, or are sent for superfluous testing, not as a result of actual medical risk, but as a result of inequities arising from the limitations inherent to the models themselves or through the inadequate collection of family history. Such use of risk assessment scores to determine access to health care would not be discriminatory on the surface, but could represent a more insidious means through which use of genetic information could create or perpetuate inequities in accessing health care. Further, as the patient inputs and the means of collecting information for breast cancer risk prediction models are similar for risk prediction models for other diseases, similar questions can be asked of other genetic-based risk prediction tools. The possibility for inequitable access resulting from the use of genetic information thus raises the following questions: What are the challenges for implementing genomic technology as a result of these limitations? Are there legal or ethical consequences? Finally, how can the potential for inequitable access be addressed during implementation?

Challenges for implementation

Limitations of breast cancer genetic risk prediction models highlight the challenges that exist for health-care professionals and governments seeking to maintain equitable access to health care when implementing technologies that use genetic information to inform medical decision making. For health-care professionals, how are they educated about underlying limitations in the tools, and how are these limitations taken into account when selecting or administering a model to a given patient? For governments and hospitals administering a publically funded health-care system, how are these limitations taken into account when selecting which models will be relied upon, and what risk thresholds will be required to establish eligibility for subsequent health care? In countries with diverse immigrant populations, how is the variable performance across ethnic groups taken into account when setting population-based thresholds? At what point is the evidence gathered on risk prediction models considered sufficient for governments and health-care professionals to rely on their use in the clinic? Simply put, how can evidence demonstrating their medical value be reconciled with the possibility of inequities arising during implementation? Failure to consider these issues during implementation would increase the likelihood that inequities could be created or perpetuated by the use of risk prediction models in medical decision making. Consequently, it becomes important to consider the consequences, legal and ethical, of possible inequities.

Legal consequences

Could inequities arising through the use of risk prediction models result in legal consequences? From an international law perspective, article 12 of the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, for which 160 nations are party, states that ‘everyone has the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health’.62 This has been interpreted by the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to mean that the Covenant ‘proscribes any discrimination in access to health care and underlying determinants of health, as well as to means and entitlements for their procurement’.63 Similarly, article 3 of the Council of Europe Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, provides that ‘parties, taking into account health needs and available resources, shall take appropriate measures with a view to providing, within their jurisdiction, equitable access to health care of appropriate quality’.64 While neither provision creates enforceable rights for individuals alleging inequitable access to health care, nevertheless such provisions have persuasive value by imposing obligations on governments to consider equitable access in their political and legislative agendas surrounding health care.65 Moreover, in jurisdictions with publically funded health-care systems, legal mechanisms can exist that allow individuals to pursue the government on questions of equitable access to health care. For example in Canada, two normative regimes exist which together have the purpose of ensuring that all Canadians have equitable access to publically funded health care. Citizens have the right under the Canadian Charter to challenge government decisions and have done so with respect to choice and availability of health-care services under the public system on the grounds that such decisions are indirectly discriminatory.66, 67 Given the national and international norms that exist surrounding equitable access to health care, it becomes prudent for nations having public and/or private health-care delivery models, to consider whether the use of genetic risk assessment scores could have for effect to deny individuals access to health care on non-medical grounds, and how to mitigate such effects during their implementation.

Ethical consequences

Beyond legal questions, the effect of excluding or testing individuals on non-medical grounds raises ethical questions of the harm that would be caused to individuals as a result. Further, inequities arising from their use raises the question as to whether such use could be inconsistent with the principle of fair distribution of resources.28 Indeed, scientific advances underlying personalized medicine genetic-based technologies are the result of enormous public investment in basic genomic sciences.12 The public is justified to expect that these discoveries will translate into products and services accessible to all, a sentiment echoed by the US National Advisory Council for Human Genome Research stating that genetic-based personalized medicine ‘will only achieve its full potential to improve health when the advances it engenders become accessible to all’.12 Others have expressed that genomic-based advances represent tools to be used to address underlying health disparities, by identifying those at risk, while those most in need should not be the last to benefit.29, 68, 69 Thus, if new personalized medicine genetic technologies have the effect of inequitably excluding individuals, thereby becoming vehicles through which disparities are perpetuated, we can ask whether the decision to rely on information from them is ethical, in light of the significant public investment underlying their development.

Conclusion

Health technology assessments and other implementation strategies are recognizing the need to improve implementation of genomic-based technologies and as a result, are integrating perspectives beyond scientific including ethical, legal, and social perspectives.70, 71, 72, 73, 74 Indeed, part of the Center for Disease Control ACCE framework for evaluating genetic tests involves considering the potential for discrimination and stigmatization as impediments to their implementation.71 However, as discussion surrounding genetic discrimination has been predominantly focused around employment or private insurance, we suggest that there is a need to consider a broader view of genetic discrimination, one which departs from the categorical conception of genetic discrimination, where it is either present or absent.

Our case study of breast cancer genetic risk prediction models illustrates how using individual genetic information in medical decision making could give rise to inequities capable of creating or perpetuating disparities in accessing health care. Further it raises legal, ethical, and implementation challenges distinct from those raised in relation to employment or private insurance. As an increasing number of medical decisions are based on individual genetic information, the potential for inequities arising from the medical use of this information also increases and it becomes important to consider this possibility. Thus, we suggest acknowledging the potential for inequitable access as occurring along a continuum ranging from inequities that could be tolerated in varying degrees, to intolerable, possibly amounting to discrimination.

Challenges have been recognized related to evaluating the ethical, legal, and social concerns raised by genetic technologies and the need to improve upon methods to identify these concerns.70, 74, 75, 76 Thus, how could concerns of inequitable access be addressed? We advocate investment in research to assess the potential for inequitable access to occur from the use of emerging genetic technologies that are used in part to determine access to health care. Such research would be conducted early on to mitigate identified concerns and would address the following questions: We suggest examining new genetic technologies to assess whether limitations exist such that their use as medical decision making tools could have the effect of creating or perpetuating inequitable access to health care. For this, evidence is needed to better understand these technologies from the perspective of the potential for inequities to occur.74, 77 For example, early assessment of the accuracy of breast cancer genetic risk prediction models compared among multiple age, socioeconomic, and ethnic backgrounds would provide an opportunity to ask whether a ‘one size fits all’ approach is appropriate or to consider the extent to which subsequent medical decisions will be based on a risk assessment. Further, we ask whether the use of genetic information in a given genetic technology for medical decision making is compatible with existing legislative regimes surrounding equitable access to health. A key remaining question is whether legislative regimes are appropriate tools to safeguard against possible inequities. Moreover, beyond legal questions raised, successful implementation requires that evidence of potential inequities arising through the use of individual genetic information be brought to the attention of and taken into consideration by health-care professionals using the technology, and by decision makers conducting health technology assessments.77 The continuum approach to characterizing inequities as advocated above would recognize the need to adjust implementation efforts so as to address the potential for inequities according to the tolerance level and the likelihood that it will occur.

The use of genomic information to inform medical decision making raises significant social, ethical, and legal questions. However, delaying implementation of tools that use genomic information until they are sufficiently perfected does not represent a realistic solution. As discussed, strong medical, legal, ethical, and economic arguments exist in favor of their use. Rather, our example points to the need to continue to invest in parallel at improving upon the limitations of these tools, as well as identifying when to supplement information from genetic-based tools with other sources of information for clinical decision making. Early identification of the potential for inequities lends an opportunity to take proportionate proactive steps to minimize the risks of inequities during implementation. By anticipating and addressing the potential for inequitable access to health care to occur from the use of genetic information, we will move closer to realizing the goal of personalized medicine: to improve health care for individuals.

References

Hamburg MA, Collins FS : The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 301–304.

Chan IS, Ginsburg GS : Personalized medicine: progress and promise. Ann Rev Genomics Human Genet 2011; 12: 217–244.

Aspinall MG, Hamermesh RG : Realizing the promise of personalized medicine. Harvard Business Rev 2007; 85: 108.

Billings PR, Kohn MA, de Cuevas M, Beckwith J, Alper JS, Natowicz MR : Discrimination as a consequence of genetic testing. Am J Hum Genet 1992; 50: 476–482.

Hudson KL : Prohibiting genetic discrimination. N Engl J Med 2007; 356: 2021–2023.

Zukerman W : Genetic discrimination in the workplace: towards legal certainty in uncertain times. J Law Med 2009; 16: 770–788.

Rothstein MA : Currents in contemporary ethics. GINA, the ADA, and genetic discrimination in employment. J Law Med Ethics 2008; 36: 837–840.

Joly Y, Braker M, Le Huynh M : Genetic discrimination in private insurance: global perspectives. New Genet Soc 2010; 29: 351–368.

Quillian L : New approaches to understanding racial prejudice and discrimination. Ann Rev Sociol 2006; 32: 299–328.

Wright CF, Burton H, Hall A et al: Next Steps in the Sequence: The Implications of Whole Genome Sequencing for Health in the UK. Cambridge: PHG Foundation, 2011.

Burke W, Burton H, Hall AE et al: Extending the reach of public health genomics: what should be the agenda for public health in an era of genome-based and ‘personalized’ medicine? Genet Med 2010; 12: 785–791.

Green ED, Guyer MS : Charting a course for genomic medicine from base pairs to bedside. Nature 2011; 470: 204–213.

Borden EC, Raghavan D : Personalizing medicine for cancer: the next decade. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9: 343–344.

Schilsky RL : Personalized medicine in oncology: the future is now. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010; 9: 363–366.

Weitzel JN, Blazer KR, MacDonald DJ, Culver JO, Offit K : Genetics, genomics, and cancer risk assessment. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 327–359.

Khoury MJ, Feero WG, Valdez R : Family history and personal genomics as tools for improving health in an era of evidence-based medicine. Am J Prev Med 2010; 39: 184–188.

Amir E, Freedman OC, Seruga B, Evans DG : Assessing women at high risk of breast cancer: a review of risk assessment models. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102: 680–691.

MacInnis RJ, Antoniou AC, Eeles RA et al: A risk prediction algorithm based on family history and common genetic variants: application to prostate cancer with potential clinical impact. Genet Epidemiol 2011; 35: 549–556.

Kratz CP, Greene MH, Bratslavsky G, Shi J : A stratified genetic risk assessment for testicular cancer. Int J Androl 2011; 34: e98–e102.

Raji OY, Agbaje OF, Duffy SW, Cassidy A, Field JK : Incorporation of a genetic factor into an epidemiologic model for prediction of individual risk of lung cancer: the Liverpool Lung Project. Cancer Prevent Res 2010; 3: 664–669.

Jostins L, Barrett JC : Genetic risk prediction in complex disease. Hum Mol Genet 2011; 20: R182–R188.

Ashley EA, Butte AJ, Wheeler MT et al: Clinical assessment incorporating a personal genome. Lancet 2010; 375: 1525–1535.

Evans GR, Lalloo F : Development of a scoring system to screen for BRCA1/2 mutations. Methods Mol Biol 2010; 653: 237.

Montori VM, Guyatt GH : Progress in evidence-based medicine. JAMA 2008; 300: 1814–1816.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS : Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996; 312: 71–72.

Evidence-based medicine: A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA 1992; 268: 2420–2425.

Canada Health Act. RSC 1985, c. C-6.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF : Principles of Biomedical Ethics. USA: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Goering S, Holland S, Edwards K : Making good on the promise of genetics: justice in translational science. Achieving Justice in Genomic Translation: Re-Thinking the Pathway to Benefit. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011, pp 1–21.

Rogowski WH, Grosse SD, Khoury MJ : Challenges of translating genetic tests into clinical and public health practice. Nat Rev Genet 2009; 10: 489–495.

Kurian AW, Gong GD, John EM et al: Performance of prediction models for BRCA mutation carriage in three racial/ethnic groups: findings from the Northern California Breast Cancer Family Registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 1084–1091.

Jacobi C, de Bock G, Siegerink B, van Asperen C : Differences and similarities in breast cancer risk assessment models in clinical practice: which model to choose? Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009; 115: 381–390.

Antoniou AC, Hardy R, Walker L et al: Predicting the likelihood of carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: validation of BOADICEA, BRCAPRO, IBIS, Myriad and the Manchester scoring system using data from UK genetics clinics. J Med Genet 2008; 45: 425–431.

Pankratz VS, Hartmann LC, Degnim AC et al: Assessment of the accuracy of the gail model in women with atypical hyperplasia. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 5374–5379.

Mackarem G, Roche CA, Hughes KS : The effectiveness of the gail model in estimating risk for development of breast cancer in women under 40 years of age. Breast J 2001; 7: 34–39.

Decarli A, Calza S, Masala G, Specchia C, Palli D, Gail MH : Gail model for prediction of absolute risk of invasive breast cancer: independent evaluation in the florence-european prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98: 1686–1693.

Antoniou AC, Durocher F, Smith P, Simard J, Easton DF : BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation predictions using the BOADICEA and BRCAPRO models and penetrance estimation in high-risk French-Canadian families. Breast Cancer Res 2006; 8: R3.

Banegas MP, Gail MH, Lacroix A et al: Evaluating breast cancer risk projections for Hispanic women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 132: 347–353.

Ulusoy C, Kepenekci I, Kose K, Aydıntug S, Cam R : Applicability of the Gail model for breast cancer risk assessment in Turkish female population and evaluation of breastfeeding as a risk factor. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2010; 120: 419–424.

Adams-Campbell LL, Makambi KH, Frederick WA, Gaskins M, Dewitty RL, McCaskill-Stevens W : Breast cancer risk assessments comparing Gail and CARE models in African-American women. Breast J 2009; 15 (Suppl 1): S72–S75.

Shojamoradi MH, Majidzadeh-A K, Najafi M, Najafi S, Abdoli N : Breast cancer risk assessment by Gail model in Iranian patients: accuracy and limitations. Eur J Cancer Suppl 2008; 6: 74–74.

Kurian AW : BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations across race and ethnicity: distribution and clinical implications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2010; 22: 72–78.

Meads C, Ahmed I, Riley RD : A systematic review of breast cancer incidence risk prediction models with meta-analysis of their performance. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 132: 365–377.

Roudgari H, Miedzybrodzka ZH, Haites NE : Probability estimation models for prediction of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: COS compares favourably with other models. Fam Cancer 2008; 7: 199–212.

Santen RJ, Boyd NF, Chlebowski RT et al: Critical assessment of new risk factors for breast cancer: considerations for development of an improved risk prediction model. Endocr Relat Cancer 2007; 14: 169–187.

Anothaisintawee T, Teerawattananon Y, Wiratkapun C, Kasamesup V, Thakkinstian A : Risk prediction models of breast cancer: a systematic review of model performances. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 133: 1–10.

Valdez R, Yoon PW, Qureshi N, Green RF, Khoury MJ : Family history in public health practice: a genomic tool for disease prevention and health promotion*. Ann Rev Public Health 2010; 31: 69–87.

American Society of Clinical Oncology: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 2397–2406.

Plat AW, Kroon AA, Van Schayck CP, De Leeuw PW, Stoffers HE : Obtaining the family history for common, multifactorial diseases by family physicians. A descriptive systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract 2009; 15: 231–242.

Berg AO, Baird MA, Botkin JR et al: National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Family History and Improving Health: August 24–26, 2009. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 2009; 26: 1–19.

Qureshi N, Carroll JC, Wilson B et al: The current state of cancer family history collection tools in primary care: a systematic review. Genet Med 2009; 11: 495–506.

Kelly KM, Sturm AC, Kemp K, Holland J, Ferketich AK : How can we reach them? Information seeking and preferences for a cancer family history campaign in underserved communities. J Health Commun 2009; 14: 573–589.

Petruccio C, Mills Shaw KR, Boughman J et al: Healthy choices through family history: a community approach to family history awareness. Comm Genet 2008; 11: 343–351.

Murff HJ, Byrne D, Haas JS, Puopolo AL, Brennan TA : Race and family history assessment for breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20: 75–80.

Murff HJ, Peterson NB, Greevy R, Zheng W : Impact of patient age on family cancer history. Genet Med 2006; 8: 438.

Murff HJ, Spigel DR, Syngal S : Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. JAMA 2004; 292: 1480–1489.

Abraham L, Geller BM, Yankaskas BC et al: Accuracy of self-reported breast cancer among women undergoing mammography. Breast Cancer Res Treatment 2009; 118: 583–592.

Dominguez FJ, Lawrence C, Halpern EF et al: Accuracy of self-reported personal history of cancer in an outpatient breast center. J Genet Counsel 2007; 16: 341–345.

Soegaard M, Jensen A, Frederiksen K et al: Accuracy of self-reported family history of cancer in a large case-control study of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2008; 19: 469–479.

Nycum G, Avard D, Knoppers B : Intra-familial obligations to communicate genetic risk information: What foundations? What forms? McGill J Law Health 2009; 3: 21–48.

Maradiegue A, Edwards QT : An overview of ethnicity and assessment of family history in primary care settings. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2006; 18: 447–456.

United Nations: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; in: Nations U (ed), 3 January 1976.

United National Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights: Substantive issues arising in the implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights: General Comment No. 14 (2000) 2000.

Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine: ETS 164, Oveido 4 April 1997.

de Groot R : Right to health care and scarcity of resources; in Gevers J, Hondius EH, Hubben J, (eds): Health Law, Human Rights and the Biomedicine Convention: Essays in Honour of Henriette Roscam Abbing. Leiden, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2005; Vol 85, pp 49–59.

Auton (Guardian ad litem of) v. British Columbia (Attorney General) 2004 SCC 78.

Flood CM : Just Medicare: What’s In, What’s Out, How We Decide. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 2006.

Burke W, Press N : What outcomes? Whose benefits?; in Burke W, Edwards K, Goering S, Holland S, Trinidad SB, (eds): Achieving Justice in Genomic Translation: Re-Thinking the Pathway to Benefit. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press, 2011, p 162.

Bustamante CD, De La Vega FM, Burchard EG : Genomics for the world. Nature 2011; 475: 163–165.

Potter BK, Avard D, Graham ID et al: Guidance for considering ethical, legal, and social issues in health technology assessment: application to genetic screening. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2008; 24: 412–422.

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention: ACCE Model List of 44 Targeted Questions Aimed at a Comprehensive Review of Genetic Testing Public Health Genomics.

Landry R, Amara N, Pablos-Mendes A, Shademani R, Gold I : The knowledge-value chain: a conceptual framework for knowledge translation in health. Bull World Health Organization 2006; 84: 597–602.

Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, Dowling N, Moore CA, Bradley L : The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: how can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genet Med 2007; 9: 665–674.

Droste S, Dintsios CM, Gerber A : Information on ethical issues in health technology assessment: how and where to find them. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2010; 26: 441–449.

Gudgeon JM, McClain MR, Palomaki GE, Williams MS, Rapid ACCE : experience with a rapid and structured approach for evaluating gene-based testing. Genet Med 2007; 9: 473–478.

Sanderson S, Zimmern R, Kroese M, Higgins J, Patch C, Emery J : How can the evaluation of genetic tests be enhanced? Lessons learned from the ACCE framework and evaluating genetic tests in the United Kingdom. Genet Med 2005; 7: 495–500.

Potter BK, Avard D, Entwistle V et al: Ethical, legal, and social issues in health technology assessment for prenatal/preconceptional and newborn screening: a workshop report. Public Health Genomics 2008; 12: 4–10.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yann Joly for critical review of the manuscript. Funding for this project is from the CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer Grant (CRN-8752-1) led by JS. KAM was supported by a CIHR Apogee- Net Post-Doctoral Fellowship. JS holds a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Oncogenetics and BMK holds a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Law and Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

McClellan, K., Avard, D., Simard, J. et al. Personalized medicine and access to health care: potential for inequitable access?. Eur J Hum Genet 21, 143–147 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.149

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.149

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Are there socio-economic inequalities in utilization of predictive biomarker tests and biological and precision therapies for cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Medicine (2020)

-

Predictive, Personalized, Preventive and Participatory (4P) Medicine Applied to Telemedicine and eHealth in the Literature

Journal of Medical Systems (2019)

-

Ethics in genetic counselling

Journal of Community Genetics (2019)

-

Testing personalized medicine: patient and physician expectations of next-generation genomic sequencing in late-stage cancer care

European Journal of Human Genetics (2014)

-

Risks of nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics? What the scientists say

Genes & Nutrition (2014)