Abstract

Background/Objectives:

To compare macronutrient intakes out of home—by location—to those at home and to investigate differences in total daily intakes between individuals consuming more than half of their daily energy out of home and those eating only at home.

Subjects/Methods:

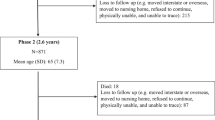

Data collected through 24-h recalls or diaries among 23 766 European adults. Participants were grouped as ‘non-substantial’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘very substantial out-of-home’ eaters based on energy intake out of home. Mean macronutrient intakes were estimated at home and out of home (overall, at restaurants, at work). Study/cohort-specific mean differences in total intakes between the ‘very substantial out-of-home’ and the ‘at-home’ eaters were estimated through linear regression and pooled estimates were derived.

Results:

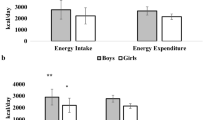

At restaurants, men consumed 29% of their energy as fat, 15% as protein, 45% as carbohydrates and 11% as alcohol. Among women, fat contributed 33% of energy intake at restaurants, protein 16%, carbohydrates 45% and alcohol 6%. When eating at work, both sexes reported 30% of energy from fat and 55% from carbohydrates. Intakes at home were higher in fat and lower in carbohydrates and alcohol. Total daily intakes of the ‘very substantial out-of-home’ eaters were generally similar to those of individuals eating only at home, apart from lower carbohydrate and higher alcohol intakes among individuals eating at restaurants.

Conclusions:

In a large population of adults from 11 European countries, eating at work was generally similar to eating at home. Alcoholic drinks were the primary contributors of higher daily energy intakes among individuals eating substantially at restaurants.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Guthrie JF, Lin BH, Frazao E . Role of food prepared away from home in the American diet, 1977-78 versus 1994-96: changes and consequences. J Nutr Educ Behav 2002; 34: 140–150.

Nielsen SJ, Siega-Riz AM, Popkin BM . Trends in energy intake in U.S. between 1977 and 1996: similar shifts seen across age groups. Obes Res 2002; 10: 370–378.

Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM . Patterns and trends in food portion sizes, 1977–1998. JAMA 2003; 289: 450–453.

Kant AK, Graubard BI . Eating out in America, 1987-2000: trends and nutritional correlates. Prev Med 2004; 38: 243–249.

Jabs J, Divine CM . Time scarcity and food choices: an overview. Appetite 2006; 47: 196–204.

Vandevijvere S, Lachat C, Kolsteren P, Van Oyen H . Eating out of home in Belgium: current situation and policy implications. Br J Nutr 2009; 102: 921–928.

Hawkes C. Marketing activities of global soft drink and fast food companies in emerging markets: a review. In: Globalization, Diets and Noncommunicable Diseases. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

Ni Mhurchu C, Aston LM, Jebb SA . Effects of worksite health promotion interventions on employee diets: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2010; 3: 62.

Kearney JM, Hulshof KFAM, Gibney MJ . Eating patterns – temporal distribution, converging and diverging foods, meals eaten inside and outside of the home – implications for developing FBDG. Publ Health Nutr 2003; 4: 693–698.

Burns C, Jackson M, Gibbons C, Stoney RM . Foods prepared outside the home: association with selected nutrients and body mass index in adult Australians. Publ Heαlth Nutr 2002; 5: 441–448.

Roos E, Sarlio-Lahteenkorva S, Lallukka T . Having lunch at a staff canteen is associated with recommended food habits. Publ Health Nutr 2004; 7: 53–61.

O’Dwyer NA, Gibney MJ, Burke SJ, McCarthy SN . The influence of location on nutrient intakes in Irish adults: implications for food-based dietary guidelines. Publ Health Nutr 2005; 8: 262–269.

Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Jacobs DR Jr et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet 2005; 365: 36–42.

Orfanos P, Naska A, Trichopoulos D, Slimani N, Ferrari P, van Bakel M et al. Eating out of home and its correlates in 10 European countries. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study. Publ Health Nutr 2007; 10: 1515–1525.

Schroder H, Fıto M, Covas MI,, REGICOR investigators. Association of fast food consumption with energy intake, diet quality, body mass index and the risk of obesity in a representative Mediterranean population. Br J Nutr 2007; 98: 1274–1280.

Marın-Guerrero AC, Gutierrez-Fisac JL, Guallar-Castillon P, Banegas JR, Rodrıguez-Artalejo F . Eating behaviours and obesity in the adult population of Spain. Br J Nutr 2008; 100: 1142–1148.

Bes-Rastrollo M, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Sanchez-Villegas A, Marti A, Martınez JA, Martınez-Gonzalez MA . A prospective study of eating away-from-home meals and weight gain in a Mediterranean population: the SUN (Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra) cohort. Publ Health Nutr 2010; 13: 1356–1363.

Lachat C, Le NBK, Nguyen CK, Nguyen QD, Nguyen DVA, Roberfroid D et al. Eating out of home in Vietnamese adolescents: socioeconomic factors and dietary associations. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 90: 1648–1655.

Orfanos P, Naska A, Trichopoulou A, Grioni S, Boer JM, van Bakel MM et al. Eating out of home: energy, macro- and micronutrient intakes in 10 European countries. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Eur J Clin Nutr 2009; 63 (Suppl 4), S239–S262.

Naska A, Orfanos P, Trichopoulou A, May AM, Overvad K, Jakobsen MU et al. Eating out, weight and weight gain. A cross-sectional and prospective analysis in the context of the EPIC-PANACEA study. Int J Obes 2011; 35: 416–426.

Kwon YS, Park YH, Choe JS, Yang YK . Investigation of variations in energy, macronutrients and sodium intake based on the places meals are provided: using the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES, 1998-2009). Nutr Res Pract 2014; 8: 81–93.

Myhre JB, Løken EB, Wandel M, Andersen LF . Eating location is associated with the nutritional quality of the diet in Norwegian adults. Public Health Nutr 2014; 17: 915–923.

Naska A, Katsoulis M, Orfanos P, Lachat C, Gedrich K, Rodrigues SS et al. Eating out is different from eating at home among individuals who occasionally eat out. A cross-sectional study among middle-aged adults from eleven European countries. Br J Nutr 2015; 113: 1951–1964.

An R . Fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption and daily energy and nutrient intakes in US adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 2016; 70: 97–103.

Lachat C, Nago E, Verstraeten R, Roberfroid D, Van Camp J, Kolsteren P . Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev 2012; 13: 329–346.

Nago ES, Lachat C, Dossa RA, Kolsteren P . Association of out-of-home eating with anthropometric changes: a systematic review of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2014; 54: 1103–1116.

Szponar L, Sekula W, Nelson M, Weisell RC . The household food consumption and anthropometric survey in Poland. Public Health Nutr 2001; 4: 1183–1186.

Turrini A, Saba A, Perrone D, Cialda E, D’Amicis A . Food consumption patterns in Italy: the INN-CA Study 1994 – 1996. Eur J Clin Nutr 2001; 55: 571–588.

Riboli E, Hunt K, Slimani N, Ferrari P, Norat T, Fahey M et al. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): study population and data collection. Publ Health Nutr 2002; 5: 1113–1124.

Szponar L, Sekuła W, Rychlik E, Oltarzewski M, Figurska K Household food consumption and anthropometric survey. Report of the Project TCP/POL/8921(A). Prace IŻŻ 101, Warszawa, Poland, 2003 (in Polish).

Schaller N, Seiler H, Himmerich S, Karg G, Gedrich K, Wolfram G et al. Estimated physical activity in Bavaria, Germany, and its implications for obesity risk: results from the BVS-II Study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2005; 8: 2–6.

Sekula W, Nelson M, Figurska K, Oltarzewski M, Weisell R, Szponar L . Comparison between household budget survey and 24-hour recall data in a nationally representative sample of Polish households. Publ Heatlh Nutr 2005; 8: 430–439.

Schätzer M, Rust P, Elmadfa I . Fruit and vegetable intake in Austrian adults: intake frequency, serving sizes, reasons for and barriers to consumption, and potential for increasing consumption. Publ Health Nutr 2010; 13: 480–487.

Brustad M, Skeie G, Braaten T, Slimani N, Lund E . Comparison of telephone vs face-to-face interviews in the assessment of dietary intake by the 24 h recall EPIC SOFT program–-the Norwegian calibration study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003; 57: 107–113.

Slimani N, Casagrande C, Nicolas G, Freisling H, Huybrechts I, Ocké MC et al. The standardized computerized 24-h dietary recall method EPIC-Soft adapted for pan-European dietary monitoring. Eur J Clin Nutr 2011; 65 (Suppl 1), S5–S15.

Lopes C, Aro A, Azevedo A, Ramos E, Barros H . Intake and adipose tissue composition of fatty acids and risk of myocardial infarction in a male Portuguese community sample. J Am Diet Assoc 2007; 107: 276–286.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–560.

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, Ministry of Health and Social Affairs of Finland. Status Report on Alcohol and Health in 35 European Countries 2013. World Health Organization: Copengagen, Denmark, 2013.

Willett WC . Nutritional Epidemiology, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998.

Orfanos P, Knüppel S, Naska A, Haubrock J, Trichopoulou A, Boeing H . Evaluating the effect of measurement error when using one or two 24 h dietary recalls to assess eating out: a study in the context of the HECTOR project. Br J Nutr 2013; 110: 1107–1117.

Subar AF, Freedman LS, Tooze JA, Kirkpatrick SI, Boushey C, Neuhouser ML et al. Addressing current criticism regarding the value of self-report dietary data. J Nutr 2015; 145: 2639–2645.

Slimani N, Deharveng G, Unwin I, Southgate DA, Vignat J, Skeie G et al. The EPIC nutrient database project (ENDB): a first attempt to standardize nutrient databases across the 10 European countries participating in the EPIC study. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007; 61: 1037–1056.

Dehne LI, Klemm C, Henseler G, Hermann-Kunz E . The German Food Code and Nutrient Database (BLS II.2). EJE 1999; 15: 355–359.

Polish Central Statistical Office Warunki z˙ Ycia Ludnos'ci w 2001 r [Living Conditions of the Population in 2001]. Studia i Analizy Statystyczne. Polish Central Statistical Office, Social Statistics Department: Warsaw, Poland, 2002 (in Polish).

Kunachowicz H, Nadolna I, Przygoda B, Iwanow K . Food composition tables. Prace IŻŻ 85. Warszawa, Poland, 1998 (in Polish).

NEVO. NEVO-Table, Dutch Food Composition Table 2001. Zeist. NEVO Foundation (in Dutch), 2001.

Food Standards Agency McCance and Widdowson's The Composition of Foods. Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2002.

NUBEL Belgian Food Composition Table. 4th edn. Ministry of Public Health: Brussels, Belgium, 2004 in Dutch.

IPL. Table de Composition des Aliments 2004. Bruxelles. Institut Paul Lambin (in French), 2004.

Carnovale E, Marletta L (eds). Tabelle di Composizione degli Alimenti. Istituto Nazionale della Nutrizione: Rome, Italy, 1997 (in Italian).

Salvini S, Parpinel M, Gnagnarella P, Maisonneuve P, Turrini A et al Banca Dati di Composizione degli Alimenti per Studi Epidemiologici in Italia [Food Composition Data-bank for Epidemiological Studies in Italy]. Istituto Europeo di Oncologia: Milan, Italy, 1998 (in Italian).

USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 17. US. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400525/Data/SR17/sr17_doc.pdf2004.

Ferreira FAG, Graça MES . . Tabela de Composição dos Alimentos Portugueses, 2ª edição. Instituto Nacional de Saúde Dr. Ricardo Jorge: Lisboa, Portugal, 1985 (in Portuguese).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted in the context of the HECTOR project entitled ‘Eating Out: Habits, Determinants, and Recommendations for Consumers and the European Catering Sector’ funded in the FP6 framework of DG-RESEARCH in the European Commission. The collection of EPIC data was performed with the financial support of the European Commission: Public Health and Consumer Protection Directorate 1993–2004; Research Directorate-General 2005, the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports (VWS), Netherlands Cancer Registry (NKR), LK Research Funds, Dutch Prevention Funds, Dutch ZON (Zorg Onderzoek Nederland), World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF), Dutch Cancer Society (KWF), Statistics Netherlands (The Netherlands); Ragusa local support; Deutsche Krebshilfe, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; Cancer Research UK; Medical Research Council, United Kingdom; Stroke Association, United Kingdom; British Heart Foundation; Department of Health, United Kingdom; Food Standards Agency, United Kingdom; Wellcome Trust, United Kingdom; the Hellenic Health Foundation, Athens, Greece; Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC); Italian National Research Council, Fondazione-Istituto Banco Napoli, Italy; AIRE ONLUS RAGUSA, Italy; Swedish Cancer Society; Swedish Scientific Council; Regional Government of Skåne, Sweden; and Nordforsk the Norwegian Cancer Society. The collection of data for the National Italian study was supported by the Consiglio per la ricerca in agricoltura e l’analisi dell’economia agraria – Centro di Ricerca per gli alimenti e la nutrizione (CRA-NUT) (former INRAN). The authors are solely responsible for the contents of the document. The opinions expressed do not represent the opinions of the Commission and the Commission is not responsible for any use that might be made of the information included. The ‘for-profit’ members of the HECTOR Consortium did not have any involvement in the collection, analysis and interpretation of dietary data and in drafting or submitting this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

*The HECTOR Consortium also consists of: Alexandra Manoli (School of Medicine, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), Patrick Kolsteren (Department of Food Safety and Food Quality, Faculty of Bioscience Engineering, Gent University, Belgium and Nutrition and Child Health Unit, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium), Maria Daniel Vaz de Almeida (Faculty of Nutrition and Food Sciences, University of Porto), Guri Skeie (Department of Community Medicine, University of Tromsø, Norway), and Wlodzimierz Sekula (National Food and Nutrition Institute, Poland).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orfanos, P., Naska, A., Rodrigues, S. et al. Eating at restaurants, at work or at home. Is there a difference? A study among adults of 11 European countries in the context of the HECTOR* project. Eur J Clin Nutr 71, 407–419 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.219

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.219

This article is cited by

-

The association between frequency of away-from home meals and type 2 diabetes mellitus in rural Chinese adults: the Henan Rural Cohort Study

European Journal of Nutrition (2020)