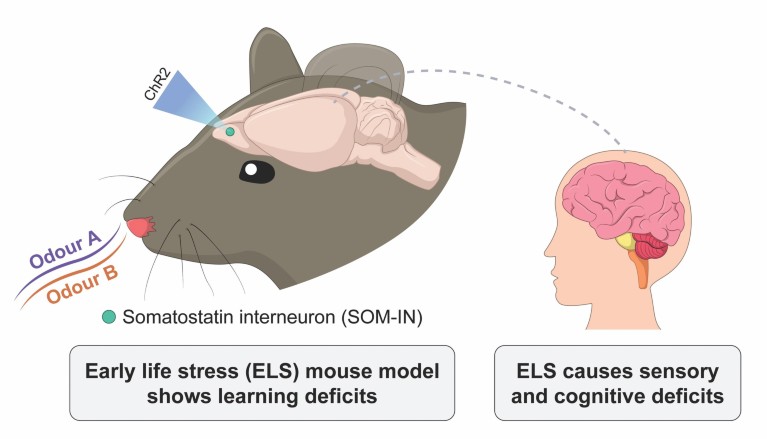

Exposure to blue light restored the activity of the somatostatin-releasing GABAergic inhibitory interneurons (SOM-INs), rescuing learning deficits in early-weaned mice. Credit: Pardasani, M. et al.

Stress in early life, such as weaning too soon, can disrupt the activity of specific interneurons in the olfactory bulb (OB), a brain region that helps to sense odours and form odour-related memories1.

Early-life stress has been shown to reduce the volume of OB in humans but how it affects neuronal networks is still a mystery.

To try to find out, neuroscientists at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Pune weaned mouse pups at two weeks, hampering mother-infant interaction.

They then trained the stressed pups on how to discriminate odours or no odours and compared them with pups who had been weaned normally and received similar training.

Each mouse was trained to lick a tube paired with a water reward in response to an odour. They also learned to avoid licking when the odour was unrewarded.

After a few hundred trials, the team, led by Nixon Abraham, found that the pace of discriminatory learning was slower in mice weaned early.

They traced this deficit to a reduction in the number and branching patterns of active cells in a specific layer of the OB that harbours most of the somatostatin-releasing GABAergic inhibitory interneurons (SOM-INs).

Using an advanced optogenetics technique, the researchers showed that exposure to blue light restored the activity of the SOM-INs, rescuing learning deficits in early-weaned mice.

This will aid the design of therapeutic approaches for stress-vulnerable interneurons in various brain dysfunctions, says Abraham.