Abstract

In order to develop an integrated pharmacokinetic/viral dynamic (PK/VD) model to predict long-term virological response rates to daclatasvir (DCV) and asunaprevir (ASV) combination therapy in patients infected with genotype 1 (GT1) chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV), a systematic publication search was conducted for DCV and ASV administered alone and/or in combination in healthy subjects or patients with GT1 HCV infection. On the basis of a constructed meta-database, an integrated PK/VD model was developed, which adequately described both DCV and ASV PK profiles and viral load time curves. The IC50 values of DCV and ASV were estimated to be 0.041 and 2.45 μg/L, respectively, in GT1A patients. A sigmoid Emax function was applied to describe the antiviral effects of DCV and ASV, depending on the drug concentrations in the effect compartment. An empirical exponential function revealed that IC50 changing over time described drug resistance in HCV GT1A patients during DCV or ASV monotherapy. Finally, the PK/VD model was evaluated externally by comparing the expected and observed virological response rates during and post-treatment with DCV and ASV combination therapy in HCV GT1B patients. Both the rates were in general agreement. Our PK/VD model provides a useful platform for the characterization of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationships and the prediction of long-term virological response rates to aid future development of direct acting antiviral drugs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 185 million people globally have been estimated to be chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which is one of the leading causes of cirrhosis and liver failure1. For the past two decades, until 2011, PEGylated interferon-α (Peg-IFN-α) in combination with ribavirin (RBV) was recommended as a standard-of-care (SOC) treatment for chronic hepatitis C2. However, fewer than 50% of patients infected with HCV genotype 1 (GT1, the most prevalent and difficult-to-cure genotype in the western world) treated with SOC achieve successful HCV treatment outcomes, ie, sustained virological response (SVR)3,4,5. Recently, novel direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) have been developed to target specific nonstructural proteins in the HCV life cycle, including NS3/4A protease inhibitors, NS5A protein inhibitors, and NS5B polymerase inhibitors6. The current approved IFN-based regimen and Peg-IFN- and RBV-free (PR-free) regimen show high potency, favorable tolerability profile, a higher barrier to resistance, shorter treatment duration, all-oral regimen, pan-genotypic character, fewer drug interactions and a decreased pill burden, as compared with the previous standard treatment7. A combination of DAA therapy, which has a good safety profile and does not include IFN or RBV that lack cross-resistance, will probably be the new recommended regimen and may possibly eradicate HCV worldwide in the near future7.

Asunaprevir (BMS650032, ASV) is a selective NS3 protease inhibitor that is rapidly absorbed over time and subsequently reaches a maximum plasma concentration (tmax) of 2–4 h and is eliminated primarily via cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4-mediated hepatic oxidative metabolism and fecal excretion, with an elimination half-life (t1/2) of 15–20 h8. Daclatasvir (BMS790052, DCV) is a first-in-class, highly selective NS5A replication complex inhibitor, which is rapidly absorbed with a tmax of 1–2 h and is mainly metabolized by hepatic CYP3A4 and excreted in fecal matter, with an elimination t1/2 of 13–15 h9,10. A drug-drug interaction (DDI) study in healthy subjects has suggested that coadministration of ASV and DCV does not result in a clinically meaningful pharmacokinetic (PK) interaction. ASV has shown activity against HCV GT1 and 4 in combination with Peg-IFN/RBV, or as part of all-oral DAA combinations in current ongoing Phase III clinical trials11,12,13. DCV was initially approved in Europe, Japan and Brazil for use in combination with other medicinal products across genotypes 1, 2, 3 and 4 for the treatment of HCV infection in adults. In July 2014, the DCV+ASV dual regimen was approved as the first all-oral, PR-free anti-HCV regimen for previously null responders to PR-treatment in Japan. In a recent global Phase III study, this all-oral dual therapy has been found to provide high rates of SVR in treatment-naïve (90%), non-responder (82%), and ineligible, intolerant, or ineligible and intolerant (82%) patients with GT1B infection14.

Modeling of PK/viral dynamics (VD) has helped to elucidate the dynamic parameters governing infection, reproduction and death of virions, production and death of infected and healthy hepatocytes, as well as the antiviral effects of DAAs15, and to investigate the possible interaction between the combined drugs16. HCV dynamic models have provided a means to compare outcomes in varied treatment regimens and in different patient populations15,17. Although many HCV dynamic models have been established for IFN or/and RBV treatment18,19,20, DAA monotherapy21,22,23,24 and combination therapy using PR and DAA agents25,26, few studies have explored and predicted the combined efficacy of DAA agents by using a PK/VD modeling approach.

In this article, we developed an integrated PK/VD model to examine the dynamics of HCV infection under DCV monotherapy and ASV monotherapy; we also used the model to predict long-term virological response rates during and post-treatment of DCV and ASV combination therapy in patients with GT1 HCV infection.

Materials and methods

Literature search and database construction

A systematic search of available information published in English in or before February 2017 was performed in PubMed, Google Scholar and the websites of National AIDS Treatment Advocacy Project (NATAP)27 and ClinicalTrials.gov by using “BMS650032”, “asunaprevir”, “BMS790052” and “daclatasvir” as keywords. Clinical studies on the PK or efficacy of DCV or ASV treatment alone, as well as these two drugs used in combination, in healthy subjects or HCV patients were included in this analysis. Additional trials were identified by cross-referencing articles.

Two independent reviewers (He-chuan WANG & Yue QIU.) constructed the dataset manually by collecting information in text or tables and extracting data from graphics, by using GetData Graph Digitizer (Version 2.24). In cases of disagreement, consensus was reached between the reviewers via discussion. The database was cross-checked by a third reviewer (Liang LI). The initial dataset consisted of viral load data, presented either as a change from the baseline and/or the actual viral load measurements, depending on the information provided in the publication. For the purpose of model analysis, the change from the baseline data was converted to actual viral load measurements for all records by adding the mean baseline value of the corresponding treatment arm.

PK/VD modeling

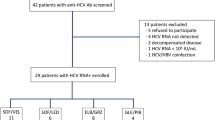

A sequential PK/VD model was developed by using a nonlinear mixed-effects modeling approach. The PK models were built separately for DCV and ASV, and this was followed by a VD model describing the interaction between the virus and the target cells, as depicted in Figure 1.

Schematic of the integrated PK/VD model structure. HCV virions (V) infect target cells (T), producing infected cells (I) at rate of β·V·T. Target cells are produced at rate constant s and die at rate constant d. Infected cells loss at rate of δ · I, and at rate of p · I produce virions (V), which are cleared at rate c · V. Ai depot compartment of drug k (k represents DCV or ASV, the same hereinafter); Xk central compartment; Pk peripheral compartment; Ce,k drug concentration in effect compartment; Qk inter-compartment clearance; Ka,k first-order absorption rate constant; Kce,k elimination rate constant from central compartment to effect compartment; Ke0,k elimination rate constant of effect compartment; CLk elimination clearance from central compartment; DASV duration of zero-order absorption for ASV; FK fraction of ASV dose absorbed by the first-order mechanism; the inhibition efficacy of viral replication E is driven by the drug concentration in effect compartment.

Software

Population analysis was performed by using a first-order conditional estimation with interaction (FOCEI) method in NONMEM (Version 7.3.0) with PsN (Version 4.2.0) and a gFORTRAN compiler (Version 4.8.2). The complete modeling process was conducted in the interface software Pirana (Version 2.8.2). Graphical data visualization, evaluation of NONMEM outputs, construction of goodness-of-fit plots and graphical model comparisons were conducted using R (Version 2.15.0).

PK models

Given the availability of only study-level aggregate PK data in our meta-database, a population-based meta-analysis approach was used to develop PK models for DCV and ASV separately. A disposition model for the drug was determined by testing a one-, two-, and three-compartment model with linear clearance. Zero-order, first-order, Michaelis-Menten saturable, and simultaneous zero- and first-order absorption processes were investigated to capture the absorption phase. Structural model selection was based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and goodness-of-fit plots. A log-normal random effect model (Equation 1) was chosen to describe the inter-arm variability (IAV) for all parameters. The additive residual error (Equation 2) was weighed by the sample size (nmk) of arm m for drug k:

where θmk is the estimated parameter value of arm m for drug k, θ^k is the typical value of the population parameter and ηθmk is specific IAV of parameter θ^k. Ymjk is the jth natural log-transformed observation in arm m for drug k, Fmjk is the model prediction, and ɛmjk is the residual error.

VD model

The VD model (Figure 1) was developed on the basis of the work of Neumann et al28 to describe the biphasic decline of HCV RNA after DCV monotherapy or ASV monotherapy treatment of HCV. The model included three variables (Equations 3–5): uninfected target cells (T), productively infected cells (I), and free virus (V). Viral infection was assumed to occur at a rate proportional to the product of the densities of virus and target cells, β·V·T (the law of mass action). Infected cells were lost by either natural death or immune attack at a rate of δ·I. Virus was released from productively infected cells at a rate of p·I and cleared at a rate of c·V. DCV or ASV was assumed to inhibit viral production with efficacy Eijk.

The viral dynamics was assumed to be at steady state prior to the initiation of therapy; therefore the initial values of the viral load (Equation 6), target cells (Equation 7) and infected cells (Equation 8) can be derived from Equations 3–5:

It was also assumed that DCV and ASV shared the same systemic parameters in the VD model. This assumption was tested by allowing for different parameter estimates for the two drugs. The maximum number of hepatocytes (TMAX), death rate of target cells d, infected cell production rate β and virion production rate p were fixed to values from the literature15.

The VD model was linked to the PK models via an effect compartment (Equation 9) to account for the possible time delay observed between plasma drug concentrations and antiviral activity, which corresponded with previously reported results29. Because only aggregate PK data were available in our analysis, the population drug concentrations in the specific arm m (Cmjk) predicted from PK models were assumed to distribute to the individual effect compartment Ce,ijk; ke,k is the rate constant governing the disposition of the drug k from the central compartment to effect compartment.

The inhibitory effect of production of virions Eijk can be described by using a sigmoid Emax function expressed by the concentration at the effect compartment Ce,ijk assuming a maximum inhibition of 100%

where IC50,ijk is the jth concentration of the ith subject in the effect compartment, which results in 50% inhibition of the virus production for the drug k, and γik is the shape factor. To capture the rebound of viral load observed in the MAD studies, which was due to the rapid emergence of viral resistance30, an empirical exponential function with a coefficient of Kr,ik revealing IC50,ijk was used. The value changed over time during therapy in the model:

Inter-individual variability (IIV) of parameters in the VD model was assumed to have a log-normal distribution. The viral load data (Vobs,ijk) and model predictions (Vpred,ijk) were log10-transformed for the modeling analysis, and their residual variability (ɛijk) was modeled by using an additive error model, as shown in Equation 12.

Covariate model

Potential covariates were tested for statistical significance for both the PK and VD models by using the stepwise forward addition method, and this was followed by a stepwise backward elimination procedure. OFV changes of 3.84 (χ2, df=1, α =0.05) or 7.88 (χ2, df=1, α=0.005) were used as a cutoff criterion for the inclusion and exclusion of the covariate, respectively. An improvement in the precision of the parameter estimate (relative standard error), and decrease in inter-arm or inter-individual and residual variability were also used to determine the importance of the covariate as a predictor.

Model evaluation and validation

A goodness-of-fit plot was assessed to reveal the model capacity for describing aggregate PK data or individual viral load data. The predictive capacity of the model was also tested by performing 500 simulations based on the parameter estimates to predict the observed virological response rates during and after combination therapy with DCV and ASV in the external validation study. In each simulation, 100 virtual subjects were generated for each of three combination dosing regimens: 1) DCV 60 mg QD+ASV 600 mg BID for 24 weeks in patients with GT1A HCV; 2) DCV 60 mg QD+ASV 200 mg QD for 24 weeks in patients with GT1B HCV and 3) DCV 60 mg QD+ ASV 200 mg BID for 24 weeks in patients with GT1B HCV. The combined antiviral efficacy ECOMB,ij of DCV and ASV was assumed to take an additive form:

In the simulation, cure or complete virion eradication was determined from the viral dynamics via implementation of a viral eradication boundary. At the timepoint at which treatment drives the system to less than one infected hepatocyte, the production of virions was set to zero. Simulated response rates were calculated as the proportion of patients whose HCV RNA measurements were below the predefined lower limit of detection (LLOD) of 10 IU/mL. Parameter uncertainty was not considered in the simulations.

Results

Included studies

A total of 25 clinical trials, representing 72 treatment arms with 362 healthy subjects and 1368 HCV-infected patients, as presented in Table 1, were included in this analysis. Of these, 18 trials provided aggregate concentration data for PK models, four trials provided individual viral load data for VD models and 7 trials provided virological response information for model evaluation. Eight trials reported DCV and ASV treated in combination, whereas results for DCV and ASV treated alone were available for 7 and 11 trials, respectively. Table 2 shows a summary of the available baseline demographic information for each study. In those 4 studies for VD modeling analysis, 82.6% of 72 HCV infected patients were treatment-naïve for PR. Only patients infected with GT1 HCV were included in these trials, and 77% of them had HCV GT1A, whereas others had GT1B. The median baseline viral load was 6.76 × 106 IU/mL.

PK model

A total of 465 aggregate DCV plasma concentrations from 198 subjects in 30 unique arms of 7 clinical trials and a total of 602 ASV aggregate concentrations from 290 subjects in 35 treatment arms of 11 clinical trials were used for PK modeling analyses. The dispositions of DCV and ASV were each well described by a two-compartment distribution model with linear elimination. The DCV absorption phase was best captured by a first-order absorption model. The SAD study in healthy subjects indicated that ASV exposure increased when it was administered as a solution (vs suspension) or with a high-fat meal, and the effect was greater for Cmax than AUC. This result suggested a saturable first-pass process, although the mechanism remains to be defined. The simultaneous zero- and first-order absorption model best described the absorption phase for ASV. The population PK parameter estimates are summarized in Table 3. All PK parameters were estimated with reasonable precision, with relative standard errors less than 30%. The goodness-of-fit plots (Figure 2) showed good agreement between the arm-level predictions and the observed plasma concentrations for both DCV and ASV. Figures 3A and 3B shows that the estimated DCV and ASV PK time profiles adequately captured the observed concentrations after single dose and multiple dose administration in healthy subjects or in HCV-infected patients.

Goodness of fit plots in log-transformed scale (A) and normal scale (B) for the PK models of DCV and ASV. Circles represent observed concentrations. Solid and dashed lines are lowess regression lines and unity lines, respectively. The size of the symbol is proportional to the precision; a larger symbol indicates a more precise (i.e., based on a larger sample size) observation.

Estimated vs observed DCV (A) PK profiles after single-dose (left panels) and multiple-dose (right panels, steady state) administration in healthy subjects, HCV patients and hepatic impairment subjects. Each symbol represents the observed mean plasma concentration at each time point in an arm of a trial and is symbol-coded by dose level. The size of the symbol is proportional to the precision; a larger symbol indicates a more precise (ie, based on a larger sample size) observation. The lines are the predicted PK time profiles based on developed PK models.

Estimated vs observed ASV (B) PK profiles after single-dose (left panels) and multiple-dose (right panels, steady state) administration in healthy subjects, HCV patients and hepatic impairment subjects. Each symbol represents the observed mean plasma concentration at each time point in an arm of a trial and is symbol-coded by dose level. The size of the symbol is proportional to the precision; a larger symbol indicates a more precise (ie., based on a larger sample size) observation. The lines are the predicted PK time profiles based on developed PK models.

PK/VD model

A total of 952 viral load measurements from 72 patients with GT1A or GT1B HCV infection receiving DCV or ASV in 2 single- and 2 multiple-ascending dose studies were pooled together to perform population VD modeling analysis. The estimated PK parameters were utilized to drive the pharmacodynamic modeling.

A summary of population pharmacodynamic parameters obtained from the final VD model is listed in Table 4. Owing to the complexity of the model, the available viral load data did not contain sufficient information to estimate all parameters precisely. Therefore, most VD system parameters were fixed to the values from the literature,15 except for virion clearance rate constant c and virion production rate constant p, which were estimated to be 20.4 per day and 148 Virions/cells/day, with relative standard errors of 22.1% and 141.1%, respectively. The inclusion of an effect compartment for both DCV and ASV in this model resulted in a significant decrease in the objective function value (ΔOFV=-92.3, df=2). The rate constants determining the equilibration process between the plasma and effect site were 0.0041 per day and 1.19 per day for DCV and ASV, respectively. The DCV concentration in the effect site was only 11% of plasma concentration after 7 days of treatment. This result was consistent with a previous finding by Ke et al29 indicating that the active tissue concentration of DCV was 10-fold lower than its plasma concentration.

A significant improvement of the fit to the data was observed for both DCV and ASV when a sigmoid Emax model, rather than the Emax model, was applied for the exposure and antiviral effect relationship. Given the limited sample size (n =40 for DCV, n=32 for ASV) and unbalanced distribution of population by genotype (n=55 for GT1A, n=17 for GT1B) in the built-in modeling database, it was difficult to estimate the IC50 of DCV and ASV for both HCV GT1A and GT1B. The differences in fold for the IC50 for GT1B vs GT1A were fixed to the values (0.18 for DCV and 0.3 for ASV) reported in previous preclinical studies13,51. The IC50 of DCV was estimated to be 0.041 μg/L (55.5 pmol/L, RSE 50.3%) and 0.0074 μg/L (10.0 pmol/L) for GT1A and GT1B replicons, respectively, thus indicating that DCV has significant potency against both the GT1A and GT1B HCV replicons. This result confirmed a previous estimate of IC50 toward the GT1 replicons (50 pmol/L against GT1A, 9 pmol/L against GT1B)51. In in vitro studies, ASV demonstrated significant antiviral activity in the HCV replicon cell systems representing GT1A and GT1B, with IC50 values of 4.0 and 1.2 nmol/L, respectively13. The IC50 of ASV in our model was estimated to be similar: 2.45 μg/L (3.2 nmol/L, RSE 96.4%) and 0.74 μg/L (0.98 nmol/L) for GT1A and GT1B replicons, respectively. The coefficients of the exponential function describing the IC50 of DCV changing over time for GT1A and GT1B replicons were estimated to be 0.43 and 0.13, respectively. This result revealed that the IC50 of DCV would increase up to 423- and 6.2-fold for GT1A and GT1B replicons after 2 weeks of DCV monotherapy, thus potentially accounting for the viral rebound experienced in most patients on or before day 7 of treatment. Because no obvious resistance-associated viral rebound emerged in ASV SAD and MAD studies, the IC50 of ASV for both GT1A and GT1B replicons would only increase 3.1-fold, even with 24 weeks of ASV monotherapy treatment, according to our prediction. The large inter-individual variability of parameter estimates might be due to the lack of individual-level plasma concentrations, the inter-study variability of viral load data and the difference in the preexistence of drug-resistant mutants within a patient population.

The goodness-of-fit plots showed no evidence of model misspecification (Figure 4), and individual prediction plots (supplementary Figures S1, S2, S3, S4) showed that the developed HCV VD model described not only the sustained viral decline and viral breakthrough during treatment but also the viral rebound after therapy.

Goodness-of-fit plots of the final VD models for (A) DCV and (B) ASV.

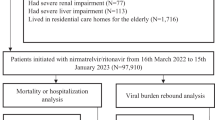

Model evaluation

The predictive performance of the model was assessed through external validation by comparing the expected and observed virological response rates in 2 Phase IIa studies (AI44701143,44 and AI44701745,46,47), 3 Asian Phase III studies (AI44702648, AI44703149 and AI44703650) and 1 global Phase III study AI44702814.

The comparison between the predicted response rates of DCV and ASV combination therapy in patients with GT1A and GT1B HCV and observations in the validation studies are shown in Figure 5. Because the 100 mg BID of the ASV softgel capsule without regard to meals used in Phase III produced similar exposures relative to 200 mg BID of Phase II tablet52, the observed virological response rates of dual treatment with DCV 60 mg QD and ASV 200 mg BID tablet or 100 mg BID softgel capsule in patients with GT1B HCV infection were pooled and evaluated in the same simulated scenario, as shown in Figure 5, panel 1. In general, the observed response rates from treatment-naïve patients, null responders or patients intolerant/ineligible to PR therapy fell within the 95% confidence intervals of the median. The simulation scenario of dual treatment of DCV 60 mg QD+ASV 200 mg QD in HCV GT1B patients intolerant to, or medically ineligible for, PR therapy is shown in Figure 5, panel 2. Although the observed complete early virological response (EVR) rate at week 12 and the end-of-treatment response (ETR) rate at week 24 were lower than the predictions, the model provided a good prediction of the rapid virologic response (RVR) rates at week 4 and SVR rates 4, 12 and 24 weeks after the end of the 24-week treatment. In HCV GT1A patients intolerant to, or medically ineligible for, PR therapy in the AI447011 sentinel cohort treated with DCV 60 mg QD+ASV 600 mg BID for 24 weeks, the observed response rates were below the 95% confidence interval therapy (Figure 5, panel 3). This result is most probably due to the small sample size (n=11) in the AI447011 sentinel cohort and to our model having been developed with viral load data derived mostly from treatment-naïve patients (approximately 80%).

Predictive performance of the PK/VD model for observed response rates of combination therapy of DCV and ASV in patients with GT1A and GT1B HCV in external validation studies. Black lines: predicted response rate curves; Gray area: 95% confidence intervals of predicted response rates; Squares: PR treatment-naïve population; Cycles: PR null responders; Triangles: PR ineligible/intolerant population. The size of the symbol is proportional to the precision; a larger symbol indicates a more precise (ie, based on a larger sample size) observation.

Discussion

In this article, we propose a PK/VD model to quantify changes in viral load with respect to changing DCV or ASV concentrations in patients with GT1 HCV. This study demonstrates a suitable strategy to predict the clinical endpoints of DCV and ASV combination therapy with early phase PK and viral load data.

To our knowledge, no previous publications have described a PK/VD model for ASV. Guedj et al21 has presented a multiscale model of HCV viral dynamics for DCV that can predict the extremely rapid decline of HCV RNA, which decreases approximately 2 logs within 6 h post-dose and is followed by a slower phase of decline. However, this multiscale model was not able to describe the viral breakthrough or viral rebound associated with persistence of DCV-resistant HCV variants observed in a MAD study53. To interpret the rapid emergence of drug-resistant HCV variants in patients treated with telaprevir, another NS3/4A protease inhibitor, Rong et al25 have developed a VD model with five variables: target cells, drug-sensitive virus, drug-resistant virus, cells infected with drug-sensitive virus, and cells infected with resistant virus. Cells infected with drug-sensitive virus were assumed to generate drug-resistant virus with low probability. The preexistence and generation of drug-resistant mutants during therapy, which were less sensitive to the drug, resulted in viral rebound and relapse. We attempted to use Rong's model to fit our data but found that this model was too complicated to converge and too time consuming in NONMEM. Therefore, a simple generalized VD model with three variables and an increasing IC50,ijk changing over time during therapy was chosen for our analysis.

According to theory54, the first phase of decline is due to treatment effectiveness in blocking viral production, E, and results in a decline in viral load at a rate near the virion clearance rate, c, with the magnitude of viral decline dependent on E. With lower amounts of virus, less de novo infection occurs, and the infected cells are not efficiently replaced, thereby generating a second phase of viral decline at a rate determined mainly by the loss rate of infected cells, δ. Thus, c and δ were the most important and sensitive parameters to capture a biphasic decline in viral load. However, only the first rapid decline phase during the first 24 h has been observed in the monotherapy studies (supplementary Figure S1 and Figure S3). After that, the viral load rebounds to the baseline level, which is mainly determined by the virion production rate p. Therefore, c and p were re-estimated for best fitting to the data, and the rest of the system-specific parameters in this VD model were fixed to the literature values. Dahari et al55 have extended this generalized model through the inclusion of homeostatic proliferation of both uninfected and infected cells, to explain the “shoulder phase” (4–28 days) of a triphasic decline in which the viral load decays slowly or remains constant. Nevertheless, such triphasic declines have been reported only in patients treated with IFN or IFN plus RBV56; moreover, these declines were not observed in our study and do not occur frequently in common clinical practice57. Furthermore, Rong et al25 have found that the proliferation of infected hepatocytes is negligible in fitting the data of another protease inhibitor, telaprevir. A sensitivity analysis of the inclusion of proliferation rates for neither, one or both uninfected and infected hepatocytes in our model was conducted. The results showed that removing the proliferation rate for both uninfected and infected cells did not result in significant changes in OFV and model performance. For simplicity, proliferation rates for hepatocytes were excluded in our VD model.

The prediction of later-phase virological response rate from early phase outcomes is a critical and challenging issue for the development of HCV antiviral agents. RVR58,59 and EVR60 are considered useful and important predictors of SVR across genotypes in patients with chronic HCV infection. However, these methods are often relatively rough and inaccurate. Many studies15,23,24,25,26 have revealed that PK/VD modeling analysis is a better, more accurate approach to predict virological response from viral load data. A common drawback of most these previous studies is that their models do not exhibit the prediction capability of virological response beyond the time range of the viral load observations. The simulation of three scenarios with different dosing regimens and populations showed that our approach provides the possibility to extrapolate predictions of external response rates during therapy and SVR rates post-treatment for HCV GT1B null responders only, by using PK and viral load data from studies no longer than 2 weeks in duration.

In the current era of anti-HCV drug therapy, combining multiple DAAs from different classes is a primary approach for improving antiviral effects, decreasing the doses of individual drugs, limiting the side effects of antiviral drugs and preventing the emergence of drug-resistant viruses16. Mathematical models of viral infection dynamics provide an ideal tool for optimizing the benefits of multi-drug combinations via the investigation of interactions between the combined drugs. Biological research exploring the mechanism of drug combination effects indicates that the relationship between two DAAs targeting different viral proteins is intermediate between additive and synergistic61. Thus, a simulation was also performed by assuming that the combined efficacy of DCV and ASV was based on the Bliss independence theory16. However, over-predictions were observed in all simulated scenarios. Ideally, intensive viral load data from a DCV and ASV combination therapy study could be used to investigate the potential pharmacodynamic interactions between DCV and ASV, which might improve prediction of response rates to combination therapy. Unfortunately, the currently available individual-level viral load data obtained from AI447011 and AI447017 were too sparse to estimate the synergistic factor between DCV and ASV.

In conclusion, the integrated PK/VD model developed in this study is the first effort to explain the complex relationships among PK exposure, short-term viral load changes and long-term virological response in HCV GT1 infected patients receiving monotherapy or combination therapy with DCV and ASV. This modeling and simulation approach may provide a useful tool for the preliminary evaluation of later-phase long-term antiviral effects of treatments with a combination of direct acting antiviral agents with different mechanisms of action in HCV patients, on the basis of the information in the PK profile and the effect on viral load changes for each antiviral agent at an early development stage.

Author contribution

Liang LI, Wei LU, Gai-Ling LI, Jenney ZHENG and Tian-yan ZHOU designed research; Liang LI, He-chuan WANG, Yu-peng REN, Yue QIU and Jenny ZHENG performed research; Liang LI, He-chuan WANG, Yu-peng REN analyzed data; and Liang LI, He-chuan WANG, Wei LU, Gai-ling LI, Chuan-pu HU wrote the paper.

References

Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST . Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013; 57: 1333–42.

Cento V, Mirabelli C, Salpini R, Dimonte S, Artese A, Costa G, et al. HCV genotypes are differently prone to the development of resistance to linear and macrocyclic protease inhibitors. PLoS One 2012; 7: e39652.

Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL. Jr, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 975–82.

Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, Rustgi VK, Shiffman M, Reindollar R, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001; 358: 958–65.

Young JL . Chronic fatigue syndrome: 3 cases and a discussion of the natural history of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Postgraduate Med 2013; 125: 162–8.

Shahid I, WH AL, Hafeez MH, Hassan S . Hepatitis C virus infection treatment: An era of game changer direct acting antivirals and novel treatment strategies. Crit Rev Microbiol 2014: 1–13.

Schinazi R, Halfon P, Marcellin P, Asselah T . HCV direct-acting antiviral agents: the best interferon-free combinations. Liver Int 2014; 34: 69–78.

Eley T, Garimella T, Li W, Bertz RJ . Asunaprevir: a review of preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetics and drug-drug interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet 2015; 54: 1205–22.

Chan P, Li H, Zhu L, Bifano M, Eley T, Osawa M, et al. Population Pharmacokinetic analysis of daclatasvir in subjects with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Pharmacokinet 2017 Jan 9. doi: 10.1007/s40262-016-0504-2.

Sato K, Yamazaki Y, Ohyama T, Kobayashi T, Horiguchi N, Kakizaki S, et al. Combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for dialysis patients infected with hepatitis C virus. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4: 88–93.

Au JS, Pockros PJ . Novel therapeutic approaches for hepatitis C. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014; 95: 78–88.

Schaefer EAK, Chung RT . Anti-hepatitis C virus drugs in development. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 1340–50.e1.

Scola PM, Sun LQ, Wang AX, Chen J, Sin N, Venables BL, et al. The discovery of asunaprevir (BMS-650032), an orally efficacious NS3 protease inhibitor for the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Chem 2014; 57: 1730–52.

Manns M, Pol S, Jacobson IM, Marcellin P, Gordon SC, Peng CY, et al. All-oral daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: a multinational, phase 3, multicohort study. Lancet 2014; 384: 1597–605.

Snoeck E, Chanu P, Lavielle M, Jacqmin P, Jonsson EN, Jorga K, et al. A comprehensive hepatitis C viral kinetic model explaining cure. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010; 87: 706–13.

Koizumi Y, Iwami S . Mathematical modeling of multi-drugs therapy: a challenge for determining the optimal combinations of antiviral drugs. Theo Biol Med Model 2014; 11: 41.

Perelson AS, Herrmann E, Micol F, Zeuzem S . New kinetic models for the hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2005; 42: 749–54.

Colombatto P, Civitano L, Oliveri F, Coco B, Ciccorossi P, Flichman D, et al. Sustained response to interferon-ribavirin combination therapy predicted by a model of hepatitis C virus dynamics using both HCV RNA and alanine aminotransferase. Antivir Ther 2003; 8: 519–30.

Derbala MF, El Dweik NZ, Al Kaabi SR, Al-Marri AD, Pasic F, Bener AB, et al. Viral kinetic of HCV genotype-4 during pegylated interferon alpha 2a: ribavirin therapy. J Viral Hepatitis 2008; 15: 591–9.

Dixit NM, Layden-Almer JE, Layden TJ, Perelson AS . Modelling how ribavirin improves interferon response rates in hepatitis C virus infection. Nature 2004; 432: 922–4.

Guedj J, Dahari H, Rong L, Sansone ND, Nettles RE, Cotler SJ, et al. Modeling shows that the NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir has two modes of action and yields a shorter estimate of the hepatitis C virus half-life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110: 3991–6.

Laouenan C, Guedj J, Mentre F . Clinical trial simulation to evaluate power to compare the antiviral effectiveness of two hepatitis C protease inhibitors using nonlinear mixed effect models: a viral kinetic approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13: 60.

Guedj J, Dahari H, Shudo E, Smith P, Perelson AS . Hepatitis C viral kinetics with the nucleoside polymerase inhibitor mericitabine (RG7128). Hepatology 2012; 55: 1030–7.

Canini L, Chatterjee A, Guedj J, Lemenuel-Diot A, Brennan B, Smith PF, et al. A pharmacokinetic/viral kinetic model to evaluate the treatment effectiveness of danoprevir against chronic HCV. Antivir Ther 2015; 20: 469–77. doi: 10.3851/IMP2879.

Rong L, Dahari H, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS . Rapid emergence of protease inhibitor resistance in hepatitis C virus. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2: 30ra32.

Nguyen TH, Mentre F, Levi M, Yu J, Guedj J . A pharmacokinetic-viral kinetic model describes the effect of alisporivir as monotherapy or in combination with peg-IFN on hepatitis C virologic response. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014; 96: 599–608.

Comings DE, Comings BG . A controlled family history study of Tourette's syndrome, I: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51: 275–80.

Neumann AU . Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon- therapy. Science 1998; 282: 103–7.

Ke R, Loverdo C, Qi H, Olson CA, Wu NC, Sun R, et al. Modelling clinical data shows active tissue concentration of daclatasvir is 10-fold lower than its plasma concentration. J Antimicrobial Chemother 2014; 69: 724–7.

McCormick AL, Wang L, Garcia-Diaz A, Macartney MJ, Webster DP, Haque T . Prevalence of baseline polymorphisms for potential resistance to NS5A inhibitors in drug-naive individuals infected with hepatitis C genotypes 1-4. Antivir Ther 2015; 20: 81–5.

Nettles RE, Chien C, Chung E, Persson A, Gao M, Belema M, et al. BMS-790052 is a First-in-class Potent Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) NS5A Inhibitor for Patients with Chronic HCV Infection: Results from a Proof-of-concept Study. 20th Conference of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver. Beijing, China: NATAP.org 2010.

Bifano M, Sevinsky H, Bedford B, Coumbis J, Eley T, Huang SP, et al. Coadministration of BMS-790052 and BMS-650032 does not result in a cinically meaningful pharmacokinetic interaction in healthy subjects. 61th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseasesed. Hynes Convention Center, Boston, MA.: NATAP.org 2010.

Nettles RE, Gao M, Bifano M, Chung E, Persson A, Marbury TC, et al. Multiple ascending dose study of BMS-790052, a nonstructural protein 5A replication complex inhibitor, in patients infected with hepatitis C virus genotype 1. Hepatology 2011; 54: 1956–65.

Shiozaki T, Ueno T, Nagashima H, Yamahira N, Hiraoka M, Eley T, et al. Single- and multiple-ascending dose studies to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of daclatasvir and asunaprevir in healthy male Japanese subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2015; 53: 292–302.

Bifano M, Sevinsky H, Persson A, Chung E, Wind-Rotolo M, Hwang C, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of daclatasvir (DCV; BMS-790052) in subjects with hepatic impairment compared with healthy subjects. 62th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. San Francisco, CA. USA: NATAP.org 2011.

Eley T . Pharmacokinetics of the NS3 protease inhibitor, asunaprevir (ASV, BMS-650032), in phase I studies in subjects with or without chronic hepatitis C. Clin Pharmacol Drug Develop 2013; 2: 316–27.

Pasquinelli C, Eley T, Villegas C, Sandy K, Mathias E, Wendelburg P, et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and antiviral activity following single- and multiple-dose administration of BMS- 650032, a novel HCV NS3 inhibitor, in subjects with chronic genotype 1 HCV infection. 60th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Boston, MA.: NATAP.org 2009.

Pasquinelli C, McPhee F, Eley T, Villegas C, Sandy K, Sheridan P, et al. Single- and multiple-ascending-dose studies of the NS3 protease inhibitor asunaprevir in subjects with or without chronic hepatitis C. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 1838–44.

Eley T, He B, Huang S, Stonier M, Bedford W, Kandoussi H, et al. Effect of multiple-dose ketoconazole and the effect of multiple-dose rifampin on the pharmacokinetics (PK) of the NS3 protease inhibitor asunaprevir. 8th International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of Hepatitis Therapy. Cambridge, MA, USA 2013.

Eley T, Han YH, Huang SP, He B, Li W, Bedford W, et al. Organic anion transporting polypeptide-mediated transport of, and inhibition by, asunaprevir, an inhibitor of hepatitis C virus NS3 protease. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2015; 97: 159–66.

Garimella T, He B, Luo WL, Colston E, Zhu K, Kandoussi H, et al. Asunaprevir pharmacokinetics and safety in subjects with impaired renal function. 64rd Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Washington, DC. USA 2013.

Bifano M, Sevinsky H, Bedford B, Coumbis J, Eley T, Huang SP, et al. Coadministration of BMS-790052 and BMS-650032 does not result in a clinically meaningful pharmacokinetic interaction in healthy subjects. 61th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases ed. Boston, MA. USA: NATAP.org 2010.

Lok AS, Gardiner DF, Lawitz E, Martorell C, Everson GT, Ghalib R, et al. Preliminary study of two antiviral agents for hepatitis C genotype 1. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 216–24.

Lok AS, Hezode C, Lawitz EJ, Bourliere M, Everson GT, Marcellin P, et al. Sustained virologic response in chronic HCV genotype (GT) 1-infected null responders with combination of daclatasvir (DCV; NS5A Inhibitor) and asunaprevir (ASV; NS3 Inhibitor[protease]) with or without peginterferon Alfa-2a/ribavirin (PEG/RBV) and triple all-oral daclatasvir+asunaprevir+Rbv (gt1a/1b). The 2013 Annual Meeting of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver. Singapore: NATAP 2013.

Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, et al. Dual oral therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for patients with HCV genotype 1b infection and limited treatment options. J Hepatol 2013; 58: 655–62.

Karino Y, Toyota J, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, et al. Characterization of virologic escape in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b patients treated with the direct-acting antivirals daclatasvir and asunaprevir. J Hepatol 2013; 58: 646–54.

Chayama K, Takahashi S, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ikeda K, Ishikawa H, et al. Dual therapy with the nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor, daclatasvir, and the nonstructural protein 3 protease inhibitor, asunaprevir, in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected null responders. Hepatology 2012; 55: 742–8.

Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, et al. Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. Hepatology 2014; 59: 2083–91.

Karino Y, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Toyota J, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, et al. All-oral dual combination of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir compared with telaprevir plus peginterferon Alfa/ribavirin in treatment-naive Japanese patients chronically infected with HCV genotype 1b. The AI447031 Study 24th Conference of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Livered. Brisbane, Australia 2014.

Wei L, Zhang MX, Xu M, Chuang WL, Lu W, Xie W, et al. Daclatasvir and asunaprevir in non-Japanese asian patients with chronic HCV genotype 1b infection who are ineligible for or intolerant to interferon-alfa therapies with or without ribavirin: phase 3 SVR12 interim results. 66th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseasesed. Boston, MA, USA 2015.

Lee C . Daclatasvir: potential role in hepatitis C. Drug Design Develop Ther 2013; 7: 1223–33.

Eley T, Sverdlov O, He B, Bedford B, Kandoussi H, Perrone R, et al. Improved bioavailability and mitigated food effect for asunaprevir (ASV) utilizing a lipid-based formulation: similar exposure with 100 mg BID softgel capsule (SGC) relative to 200 mg BID of phase 2 tablet. Interscience Conference of Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. San Francisco: ICAAC 2012.

Wang C, Sun JH, O'Boyle DR, 2nd, Nower P, Valera L, Roberts S, et al. Persistence of resistant variants in hepatitis C virus-infected patients treated with the NS5A replication complex inhibitor daclatasvir. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 2054–65.

Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, et al. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science 1998; 282: 103–7.

Dahari H, Ribeiro RM, Perelson AS . Triphasic decline of hepatitis C virus RNA during antiviral therapy. Hepatology 2007; 46: 16–21.

Canini L, Perelson AS . Viral kinetic modeling: state of the art. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 2014; 41: 431–43.

Dahari H, Guedj J, Perelson AS, Layden TJ . Hepatitis C viral kinetics in the era of direct acting antiviral agents and IL28B. Curr Hepatitis Rep 2011; 10: 214–27.

Poordad F, Reddy KR, Martin P . Rapid virologic response: a new milestone in the management of chronic hepatitis C. Clin Infectious Dis 2008; 46: 78–84.

Fried MW, Hadziyannis SJ, Shiffman ML, Messinger D, Zeuzem S . Rapid virological response is the most important predictor of sustained virological response across genotypes in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2011; 55: 69–75.

Ferenci P, Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Smith CI, Marinos G . Goncales FL Jr, et al. Predicting sustained virological responses in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with peginterferon alfa-2a (40 KD)/ribavirin. J Hepatol 2005; 43: 425–33.

Gao M, Nettles RE, Belema M, Snyder LB, Nguyen VN, Fridell RA, et al. Chemical genetics strategy identifies an HCV NS5A inhibitor with a potent clinical effect. Nature 2010; 465: 96–100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary information is available at the website of Acta Pharmacologica Sinica.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figure S1–S4 (DOC 128 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Hc., Ren, Yp., Qiu, Y. et al. Integrated pharmacokinetic/viral dynamic model for daclatasvir/asunaprevir in treatment of patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. Acta Pharmacol Sin 39, 140–153 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2017.84

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2017.84