Abstract

To investigate the little known risk of lung cancer at an early age when a first-degree relative has had such a diagnosis, 579 incident cases and 1157 population controls were studied in Liverpool between 1998 and 2004 using standardised questionnaires covering demography and lifestyle. A history of lung cancer in first-degree relatives was associated with a significantly increased risk in the proband where in both individuals the cancers were diagnosed before the age of 60 years (odds ratio (OR)=4.89; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.47–16.25). A significantly elevated risk of lung cancer was also observed in association with a relative affected before the age of 60 years, regardless of age-at-onset of the disease (OR=2.08; 95% CI: 1.20–3.59). This finding is strongly consistent with a genetic component in early-onset lung cancer risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Smoking is well established as the major aetiological risk factor for lung cancer. Investigators have long hypothesised that individuals differ in their susceptibility to environmental insults and that these differences may be the result of genetic predisposition (Schwartz, 2004). Familial aggregation and increased familial risk for lung cancer have been reported in several studies, providing indirect evidence that genetic factors contribute to susceptibility to lung cancer (Yang et al, 1999; Etzel et al, 2003; Matakidou et al, 2005; Xu et al, 2005). Recently, a major lung cancer susceptibility locus was mapped to chromosome 6q23–35 through a genome-wide linkage analysis, further supporting the role of genetic factors in the susceptibility of lung cancer (Bailey-Wilson et al, 2004). Biological theory and the experience of other cancers, including breast (Hopper et al, 1999), pancreas (James et al, 2004) and colon (Strate and Syngal, 2005), suggest that tumours associated with genetic factors tend to occur early in life. Numerous lung cancer studies have investigated the numbers of affected relatives and age-at-onset, with greatest risk seen in families with early-onset lung cancer compared with those whose onset of lung cancer occurred at older ages (Kreuzer et al, 1998; Bromen et al, 2000; Gauderman and Morrison 2000; Li and Hemminki, 2004; Cote et al, 2005). However, information on familial risk by age-at-onset of both the proband and the affected relatives is rare in lung cancer studies. Here we report results for a case–control study that examines age-at-onset in both lung cancer cases and affected relatives.

Materials and methods

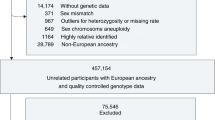

The lung cancer case–control data were derived from an ongoing molecular–epidemiological study of lung cancer in Liverpool, UK, The Liverpool Lung Project (Field et al, 2005). Histologically or cytologically confirmed lung cancer cases with primary tumours, resident within the study area, were recruited from participating chest clinics. Population controls were selected from registers of general practitioners in Liverpool and matched to cases by 2-year age group and gender.

A standardised questionnaire was used to determine basic demographic characteristics in addition to details on smoking history, family history of cancer in first-degree relatives and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS). Lifetime smoking histories were recorded, covering: (i) ever smoked (never-smoker defined as someone who had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in his or her lifetime); (ii) current smoker (yes or no); (iii) duration of smoking (years); (iv) pack-years (calculated from the number of cigarette packs (of 20) smoked per day and years of smoking); and (v) amount smoked (average number of cigarettes per day). Environmental tobacco smoke exposure was defined as being in the presence of a smoker on a regular basis. Exposures to ETS at home, work and in public places (e.g. bars) were recorded separately. Information on history of cancer among first-degree relatives (i.e. parents, brothers and sisters and biological children) were recorded, including age-at-diagnosis, site of cancer and relation to the participant. These data were not validated by death certificate, and smoking information of relatives was not obtained. Individuals were defined as having a history of familial lung cancer if at least one relative with lung cancer was reported. The study protocol was approved by the Liverpool Research Ethic Committee and all research participants provided written, informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Principle.

Statistical analyses

Significance tests for differences in distributions between cases and controls, odds ratio (OR) estimates of relative risk and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were all estimated using conditional logistic regression. Early- and late-onset lung cancers were defined as before the age of 60 years and at the age of 60 years or later, respectively, in accordance with the average age of lung cancer diagnoses in our study population. To determine whether the risk of developing lung cancer is greater for relatives of cases with early- and late-onset lung cancer, we performed analyses stratified for (i) cases diagnosed before the age of 60 years and at the age of 60 years or later; and (ii) first-degree relatives diagnosed with lung cancer before the age of 60 years and at the age of 60 years or later. Models were adjusted for smoking duration (five categories), ETS exposure at home, work and in public (two categories) and socioeconomic status (six categories). All analyses were performed using STATA.

Results

Five hundred and seventy-nine incident cases of lung cancer and 1157 population controls were recruited between 1998 and 2004. Overall, the response rate was 58.3% for cases and 61.5% for controls. Table 1 shows the distribution of cases and controls by number of affected relatives, smoking, socioeconomic status and ETS exposure. As expected, the proportion of ever smokers was higher among cases (95.3%) compared with controls (71%), with significant differences observed in terms of duration of smoking (P<0.001). The proportion of cases with two or more first-degree relatives was more than twice that of the controls: 5.2 and 2.3%, respectively (P=0.03). There were also significant differences between cases and controls in socioeconomic status (P<0.001) and exposure to ETS in the home (P<0.001). Borderline significant differences were observed for exposure to ETS at work (P=0.07).

Although there was a significant trend of increasing risk with numbers of affected relatives (Table 1), there was no significant effect of family history (any vs none) of lung cancer in the study population overall or in late-onset cases, regardless of the age of affected relatives. There was, however, a substantial and statistically significant increase in risk where both the lung cancer case and the affected relative were diagnosed with lung cancer before the age of 60 years (OR=4.89; 95% CI: 1.47, 16.25) (P=0.01). Significantly elevated ORs were also observed in connection with an affected relative diagnosed before the age of 60 years, regardless of age-at-onset of the case (OR=2.08; 95% CI: 1.20, 3.59) (Table 2). The interaction did not reach formal statistical significance (P=0.1).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate an approximate five-fold increase in risk of lung cancer in individuals aged less than 60 years if first-degree relatives were diagnosed with early-onset lung cancer (i.e. less than 60 years old). We also found a significantly increased risk associated with family history regardless of age-at-onset. The increase in familial risk reported in younger individuals supports the hypothesis that there is a greater likelihood of a genetic component to risk in this group. Previous studies of familial aggregation suggest that family history of lung cancer among first-degree relatives is associated with increased risk for early-onset, but not late-onset, lung cancer. Kreuzer et al (1998) reported that lung cancer in a first-degree relative was associated with a 2.6-fold increase in risk of lung cancer of young cases (before 46 years of age), with no elevated risk observed in the older group. Bromen et al (2000) reported a 4.75-fold increase in risk of lung cancer among relatives of probands who were diagnosed with lung cancer before the age of 50 years. Li and Hemminki (2004) used a Swedish register of families to estimate standardised incidence ratio for offspring and siblings of cases of lung cancer, and found a substantially increased risk of disease before the age of 50 years in relatives of cases. In an alternative analysis to quantify the lifetime risk of lung cancer in first-degree relatives of early-onset cases diagnosed before the age of 50 years, Cote et al (2005) reported a 1.91-fold increased risk of lung cancer for relatives of early-onset cases compared to affected relatives in a control population.

Our results concur with previous reports, but while others have observed age-specific effects in familial lung cancer risk, this is the first study, to our knowledge, demonstrating an increased risk of lung cancer when both the lung cancer case and the affected relative were diagnosed at younger ages. It is difficult for epidemiology to provide conclusive evidence that the accumulation of lung cancer risk has a genetic origin. Cautious interpretation of familial effects on lung cancer risk is therefore required because of the possibility that elevated relative risks are due to shared smoking habits within families (Khoury et al, 1988). However, it is difficult to envisage how such confounding could be very strong at young ages and almost nonexistent at older. It is therefore likely that our observed additional risk for early onset disease associated with family history is not due to such confounding. Furthermore, a recent segregation analysis of lung cancer pedigrees, allowing for the effects of smoking sex and age, suggests that multiple genetic factors (possibly multiple genetic loci and interactions) contribute to susceptibility and age-of-onset for lung cancer (Xu et al, 2005). The particularly high risk observed in our study associated with early onset in both the proband and the affected relatives adds to the evidence of a genetic component.

In our study, smoking information allowed a detailed adjustment in the analyses. In addition, we controlled for other known environmental factors, such as socioeconomic status and ETS, which have previously been associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. A limitation of the present study pertains to the use of self-reported family history of cancer, which may result in inaccurate risk estimates. Bondy et al (1994) evaluated the validity of proband-reported family history of cancer using medical records and death certificates, noting that 85% of probands correctly identified primary lung cancer in first-degree relatives. However, a recent cancer registry study linking individuals to their first-degree family members suggests that in case–control studies of a specific cancer type, cases are more likely than controls to report both true-positive and false-positive family histories of their particular cancer, resulting in inflated estimates of the relative risk (Chang et al, 2006). Another limitation of the present study is the possibility of recall bias or other biases in determination of family history in a case–control design (Khoury and Flanders, 1995; Kreuzer et al, 1998). Furthermore, because the age-at-onset among relatives was reported by the lung cancer case, inaccuracies may lead to information bias. It is unlikely, however, that such biases could lead to effects as substantial and specific as observed in our study. In conclusion, our study found a substantial and significant increase in risk of having lung cancer before the age of 60 years exclusively associated with a relative having also had lung cancer diagnosed before the age of 60 years. This remains significant after adjustment for smoking, socioeconomic status and ETS exposure and is consistent with a genetic component to risk in early-onset lung cancer.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Bailey-Wilson JE, Amos CI, Pinney SM, Petersen GM, de Andrade M, Wiest JS, Fain P, Schwartz AG, You M, Franklin W, Klein C, Gazdar A, Rothschild H, Mandal D, Coons T, Slusser J, Lee J, Gaba C, Kupert E, Perez A, Zhou X, Zeng D, Liu Q, Zhang Q, Seminara D, Minna J, Anderson MW (2004) A major lung cancer susceptibility locus maps to chromosome 6q23–25. Am J Hum Genet 75: 460–474

Bondy ML, Strom SS, Colopy MW, Brown BW, Strong LC (1994) Accuracy of family history of cancer obtained through interviews with relatives of patients with childhood sarcoma. J Clin Epidemiol 47: 89–96

Bromen K, Pohlabeln H, Jahn I, Ahrens W, Jockel KH (2000) Aggregation of lung cancer in families: results from a population-based case–control study in Germany. Am J Epidemiol 52: 497–505

Chang ET, Smedby KE, Hjalgrim H, Glimelius B, Adami HO (2006) Reliability of self-reported family history of cancer in a large case–control study of lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 98: 61–68

Cote ML, Kardia SL, Wenzlaff AS, Ruckdeschel JC, Schwartz AG (2005) Risk of lung cancer among white and black relatives of individuals with early-onset lung cancer. JAMA 293: 3036–3042

Etzel CJ, Amos CI, Spitz MR (2003) Risk for smoking-related cancer among relatives of lung cancer patients. Cancer Res 63: 8531–8535

Field JK, Smith DL, Duffy SW, Cassidy A (2005) The Liverpool Lung Project Research Protocol. Int J Oncol 27: 1633–1645

Gauderman WJ, Morrison JL (2000) Evidence for age-specific genetic relative risks in lung cancer. Am J Epidemiol 151: 41–49

Hopper JL, Southey MC, Dite GS, Jolley DJ, Giles GG, McCredie MR, Easton DF, Venter DJ (1999) Population-based estimate of the average age-specific cumulative risk of breast cancer for a defined set of protein-truncating mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Australian breast cancer family study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8: 741–747

James TA, Sheldon DG, Rajput A, Kuvshinoff BW, Javle MM, Nava HR, Smith JL, Gibbs JF (2004) Risk factors associated with earlier age of onset in familial pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 101: 2722–2726

Khoury MJ, Beaty TH, Liang KY (1988) Can familial aggregation of disease be explained by familial aggregation of environmental risk factors? Am J Epidemiol 127: 674–683

Khoury MJ, Flanders WD (1995) Bias in using family history as a risk factor in case–control studies of disease. Epidemiology 6: 511–519

Kreuzer M, Kreienbrock L, Gerken M, Heinrich J, Bruske-Hohlfeld I, Muller KM, Wichmann HE (1998) Risk factors for lung cancer in young adults. Am J Epidemiol 147: 1028–1037

Li X, Hemminki K (2004) Inherited predisposition to early-onset lung cancer according to histological type. Int J Cancer 112: 451–457

Matakidou A, Eisen T, Bridle H, O'Brien M, Mutch R, Houlston RS (2005) Case–control study of familial lung cancer risks in UK women. Int J Cancer 116: 445–450

Schwartz AG (2004) Genetic predisposition to lung cancer. Chest 125: 86S–89S

Strate LL, Syngal S (2005) Hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes. Cancer Causes Control 16: 201–213

Xu H, Spitz MR, Amos CI, Shete S (2005) Complex segregation analysis reveals a multigene model for lung cancer. Hum Genet 116: 121–127

Yang P, Schwartz AG, McAllister AE, Swanson GM, Aston CE (1999) Lung cancer risk in families of nonsmoking probands: heterogeneity by age at diagnosis. Genet Epidemiol 17: 253–273

Acknowledgements

The Liverpool Lung Project is funded by the Roy Castle Foundation. JPM is funded by Cancer Research UK (Grant No. C8649/A5367).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cassidy, A., Myles, J., Duffy, S. et al. Family history and risk of lung cancer: age-at-diagnosis in cases and first-degree relatives. Br J Cancer 95, 1288–1290 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603386

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603386

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Health effects associated with exposure to secondhand smoke: a Burden of Proof study

Nature Medicine (2024)

-

Risk of breast cancer and family history of other cancers in first-degree relatives in Chinese women: a case control study

BMC Cancer (2014)

-

First degree relatives and familial aggregation of gastric cancer: who to choose for control in case–control studies?

Familial Cancer (2012)

-

Family history and lung cancer risk: international multicentre case–control study in Eastern and Central Europe and meta-analyses

Cancer Causes & Control (2010)

-

Socioeconomic differences in lung cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Cancer Causes & Control (2009)