Abstract

Over 250 000 patients each year undergo a spine fusion procedure in the US. This constitutes 50% of all bone graft procedures. Despite best efforts, a large percentage of spine fusions (up to 35%) fail to form a solid bony arthrodesis. This is a significant clinical problem and has led to research in bone formation biology to augment spine fusion rates. Both recombinant and purified osteoinductive cytokines have been studied in pilot and pivotal studies in humans. At this point, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 has received FDA approved for lumbar interbody application with titanium cages. Despite these successes, limitations of directly applying osteoinductive proteins related to cost and carriers remain to be overcome. Gene therapy for spine fusion and other bone healing applications are being pursued as an alternative strategy. This article will review the state of the art of local gene therapy for bone formation and to highlight specific issues, which must be addressed when pursuing such a program. A critical step in using gene therapy for bone formation is choosing an appropriate osteoinductive gene. In choosing the gene, one must consider the differences in efficacy of the gene as well as the gene availability due to proprietary constraints. The choice of delivery vector is important. Factors such as the potency of the gene and the specific application intended play a role in this decision. Next, the effective dose, transduction time, and gene transfer method must be established. The choice of carrier material to form the scaffold for the new bone formation is another critical step that must be optimized for successful bone formation. Finally, a strategy for in vitro and in vivo testing must be developed to maximize the chances of success in human trials.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

DePalma AF, Rothman RH . The nature of pseudarthrosis. Clin Orthop 1968; 59: 113–118.

Steinmann JC, Herkowitz HN . Pseudarthrosis of the spine. Clin Orthop 1992; 284: 80–90.

Zoma A et al. Surgical stabilisation of the rheumatoid cervical spine: a review of indications and results. J Bone Joint Surg 1987; 49-B: 8–12.

Ferlic DC et al. Surgical treatment of the symptomatic unstable cervical spine in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg 1975; 57-A: 349–354.

Conaty JP, Mongan ES . Cervical fusion in rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg 1981; 63-A: 1218–1227.

West III JL, Bradford DS, Ogilvie JW . Results of spinal arthrodesis with pedicle screw plate fixation. J Bone Joint Surg 1991; 73-A: 1179–1184.

Bridwell KH et al. The role of fusion and instrumentation in the treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord 1993; 6: 461–472.

McGuire RA, Amundson GM . The use of primary internal fixation in spondylolisthesis. Spine 1993; 18: 1662–1672.

Zdeblick TA . A prospective, randomized study of lumbar fusion: Preliminary results. Spine 1993; 18: 983–991.

Brodsky AE, Kovalsky ES, Khalil MA . Correlation of radiographic assessment of lumbar spine fusions with surgical exploration. Spine 1991; 16: S261–S265.

Boden SD . Bone repair and enhancement clinical trial design. Spine applications. Clin Orthop 1998: S336–S346.

Schimandle JH, Boden SD . The use of animal models to study spinal fusion. Spine 1994; 19: 1998–2006.

Boden SD, Schimandle JH, Hutton WC . An experimental lumbar intertransverse process spinal fusion model: radiographic, histologic, and biomechanical healing characteristics. Spine 1995; 20: 412–420.

Urist MR . Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science 1965; 150: 893–899.

Urist MR, Strates BS . Bone morphogenetic protein. J Dent Res Suppl 1971; 50: 1392–1406.

Teixeira JOC, Urist MR . Bone morphogenetic protein induced repair of compartmentalized segmental diaphyseal defects. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1998; 117: 27–34.

Johnson EE, Urist MR, Finerman GAM . Resistant nonunions and partial or complete segmental defects of long bones: treatment with implants of a composite of human bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) and autolyzed, antigen-extracted, allogeneic (AAA) bone. Clin Orthop 1992; 277: 229–237.

Johnson EE, Urist MR, Finerman GAM . Bone morphogenetic protein augmentation grafting of resistant femoral nonunions: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop 1988; 230: 257–265.

Wozney JM et al. Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science 1988; 242: 1528–1534.

Ozkaynak E et al. OP-1 cDNA encodes an osteogenic protein in the TGF-b family. Eur Mol Biol Organ J 1990; 9: 2085–2093.

Sampath TK, Muthukumaran N, Reddi AH . Isolation of osteogenin, an extracellular matrix-associated, bone-inductive protein, by heparin affinity chromatography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987; 84: 7109–7113.

Boden SD, Schimandle JH, Hutton WC . 1995 Volvo Award in Basic Sciences. The use of an osteoinductive growth factor for lumbar spinal fusion. Part II: study of dose, carrier, and species. Spine 1995; 20: 2633–2644.

Martin GJ et al. Posterolateral intertransverse process spinal fusion arthrodesis with rhBMP-2 in a non-human primate-Important lessons learned regarding dose, carrier, and safety. J Spinal Disord 1999; 12: 179–186.

Boden SD et al. Laparoscopic anterior spinal arthrodesis with rhBMP-2 in a titanium interbody threaded cage. J Spinal Disord 1998; 11: 95–101.

Boden SD, Schimandle JH, Hutton WC . Evaluation of a bovine-derived osteoinductive bone protein in a non-human primate model of lumbar spinal fusion. Trans Orthop Res Soc 1996; 21: 118.

Boden SD et al. The use of rhBMP-2 in interbody fusion cages. Definitive evidence of osteoinduction in humans: a preliminary report. Spine 2000; 25: 376–381.

McKay B, Sandhu HS . Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in spinal fusion applications. Spine 2002; 27: S66–S85.

Vaccaro AR, Anderson DG, Toth CA . Recombinant human osteogenic protein-1 (bone morphogenetic protein-7) as an osteoinductive agent in spinal fusion. Spine 2002; 27: S59–S65.

Damien CJ et al. Purified bovine BMP extract and collagen for spine arthrodesis: preclinical safety and efficacy. Spine 2002; 27: S50–S58.

Louis-Ugbo J et al. Retention of 125I-labeled recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein- 2 by biphasic calcium phosphate or a composite sponge in a rabbit posterolateral spine arthrodesis model. J Orthop Res 2002; 20: 1050–1059.

Muschler GF et al. Treatment of established tibial nonunions using recombinant osteogenic protein-1. Trans Am Acad Orthop Surg 1998; 65: 172–173.

Jeppsson C et al. OP-1 for cervical spine fusion: bridging bone in only 1 of 4 rheumatoid patients but prednisolone did not inhibit bone induction in rats. Acta Orthop Scand 1999; 70: 559–563.

Laursen M et al. Recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-7 as an intracorporal bone growth stimulator in unstable thoracolumbar burst fractures in humans: preliminary results. Eur Spine J 1999; 8: 485–490.

Fang J et al. Stimulation of new bone formation by direct transfer of osteogenic plasmid genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 5753–5758.

Lieberman JR et al. Regional gene therapy with a BMP-2-producing murine stromal cell line induces heterotopic and orthotopic bone formation in rodents. Journal of Orthopaedic Research 1998; 16: 330–339.

Okubo Y et al. In vitro and in vivo studies of a bone morphogenetic protein-2 expressing adenoviral vector. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A (Suppl 1): S99–104.

Bosch P et al. The efficiency of muscle-derived cell-mediated bone formation. Cell Transplant 2000; 9: 463–470.

Musgrave DS et al. Human skeletal muscle cells in ex vivo gene therapy to deliver bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84: 120–127.

Lou J et al. Gene therapy: adenovirus-mediated human bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene transfer induces mesenchymal progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in vitro and bone formation in vivo. J Orthop Res 1999; 17: 43–50.

Partridge K et al. Adenoviral BMP-2 gene transfer in mesenchymal stem cells: in vitro and in vivo bone formation on biodegradable polymer scaffolds. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2002; 292: 144–152.

Lee JY et al. Effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2-expressing muscle-derived cells on healing of critical-sized bone defects in mice. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A: 1032–1039.

Lee JY et al. Enhancement of bone healing based on ex vivo gene therapy using human muscle-derived cells expressing bone morphogenetic protein 2. Hum Gene Ther 2002; 13: 1201–1211.

Moutsatsos IK et al. Exogenously regulated stem cell-mediated gene therapy for bone regeneration. Mol Ther 2001; 3: 449–461.

Gazit D et al. Engineered pluripotent mesenchymal cells integrate and differentiate in regenerating bone: a novel cell-mediated gene therapy. J Gene Med 1999; 1: 121–133.

Lieberman JR et al. The effect of regional gene therapy with bone morphogenetic protein-2-producing bone-marrow cells on repair of segmental femoral defects in rats. J Bone Joint Surg 1999; 81-A: 905–917.

Riew KD et al. Induction of bone formation using a recombinant adenoviral vector carrying the human BMP-2 gene in a rabbit spinal fusion model. Calcif Tissue Int 1998; 63: 357–360.

Franceschi RT et al. Gene therapy for bone formation: in vitro and in vivo osteogenic activity of an adenovirus expressing BMP7. J Cell Biochem 2000; 78: 476–486.

Rutherford RB et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-transduced human fibroblasts convert to osteoblasts and form bone in vivo. Tissue Eng 2002; 8: 441–452.

Breitbart AS et al. Gene-enhanced tissue engineering: applications for bone healing using cultured periosteal cells transduced retrovirally with the BMP-7 gene. Ann Plast Surg 1999; 42: 488–495.

Dumont RJ et al. Ex vivo bone morphogenetic protein-9 gene therapy using human mesenchymal stem cells induces spinal fusion in rodents. Neurosurgery 2002; 51: 1239–1245.

Musgrave DS et al. Adenovirus-mediated direct gene therapy with bone morophogenetic protein-2 produces bone. Bone 1999; 24: 541–547.

Alden TD et al. In vivo endochondral bone formation using a bone morphogenetic protein 2 adenoviral vector. Hum Gene Ther 1999; 10: 2245–2253.

Alden TD et al. The use of bone morphogenetic protein gene therapy in craniofacial bone repair. J Craniofac Surg 2000; 11: 24–30.

Alden TD et al. Percutaneous spinal fusion using bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene therapy. J Neurosurg 1999; 90 (Spine 1): 109–114.

Boden SD et al. 1995 Volvo Award in Basic Sciences. The use of an osteoinductive growth factor for lumbar spinal fusion. Part I: the biology of spinal fusion. Spine 1995; 20: 2626–2632.

Boden SD, Sumner DR . Biologic factors affecting spinal fusion and bone regeneration. Spine 1995; 20: 102S–112S.

Liu Y et al. BMP-6 induces a novel LIM protein involved in bone mineralization and osteocalcin secretion. J Bone Min Res 1997; 12: S115.

Dawid IB, Breen JJ, Toyama R . LIM domains: multiple roles as adapters and functional modifiers in protein interactions. Trends Genet 1998; 14: 156–162.

Smith AE . Viral vectors in gene therapy. Annu Rev Microbiol 1995; 49: 807–838.

Wagner E et al. Transferrin-polycation conjugates as carriers for DNA uptake into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87: 3410–3414.

Baltzer AWA et al. A gene therapy approach to accelerating bone healing. Evaluation of gene expression in a New Zealand white rabbit model. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1999; 7: 197–202.

Guzman RJ et al. In vivo suppression of injury-induced vascular smooth muscle cell accumulation using adenovirus-mediated transfer of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994; 91: 10732–10736.

Watanabe T et al. Enhancement of adenovirus-mediated gene transfer to human bone marrow cells. Leukemia Lymphoma 1998; 29: 439–451.

Xiao W et al. Adeno-associated virus as a vector for liver-directed gene therapy. J Virol 1998; 72: 10222–10226.

Blomer U et al. Highly efficient and sustained gene transfer in adult neurons with a lentivirus vector. J Virol 1997; 71: 6641–6649.

Goldman MJ et al. Lentiviral vectors for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Hum Gene Ther 1997; 10: 2261–2268.

Boden SD et al. LMP-1, A LIM-domain protein, mediates BMP-6 effects on bone formation. Endocrinology 1998; 139: 5125–5134.

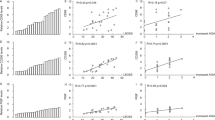

Boden SD et al. 1998 Volvo Award in Basic Sciences: lumbar spine fusion by local gene therapy with a cDNA encoding a novel osteoinductive protein (LMP-1). Spine 1998; 23: 2486–2492.

Viggeswarapu M et al. Adenoviral delivery of LIM mineralization protein-1 induces new-bone formation in vitro and in vivo. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A: 364–376.

Kozak M . Possible role of flanking nucleotides in recognition of the AUG initiator codon by eukaryotic ribosomes. Nucleic Acids Res 1981; 9: 5233–5262.

Kozak M . Compilation and analysis of sequences upstream from the translational start site in eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 1984; 12: 857–872.

Kozak M . At least six nucleotides preceding the AUG initiator codon enhance translation in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol 1987; 196: 947–950.

Kozak M . Downstream secondary structure facilitates recognition of initiator codons by eukaryotic ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987; 87: 8301–8305.

Kozak M . Recognition of AUG and alternative initiator codons is augmented by G in position +4 but is not generally affected by the nucleotides in positions +5 and +6. EMBO J 1997; 16: 2482–2492.

Suh DY et al. Delivery of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2) using a compression resistant matrix in posterolateral spine fusion in the rabbit and non-human primate. Spine 2002; 27: 353–360.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, S., Boden, S. Spine fusion by gene therapy. Gene Ther 11, 360–367 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3302203

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3302203

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Genetically modified mesenchymal stem cells promote spinal fusion through polarized macrophages

Laboratory Investigation (2022)

-

Endoskopische Knochentransplantation an der Wirbels�ule

Der Unfallchirurg (2004)