Science communication is a tricky business. The goal sounds simple: translate scientific findings into concise, engaging pieces for the general public. But the devil in the details offers some hazards and temptations. Sifting through complex scientific articles brimming with jargon takes a bit of time, and finding the hook to grab readers buried within methods and results can be frustrating. Even more important than these difficulties, however, is the accurate portrayal of the major scientific findings.

The last point is the most important but also the rule most easily broken. The hope of any aspiring science communicator is to attract an audience. While we all hope we can do this through the sweet smell of science and hard facts alone, sexy headlines and one-liners are usually more appealing aromas. But what is the cost of these tactics when trying to foster public trust and support for the sciences?

Vegetables in the headlines

This struggle between selling and reporting scientific findings has appeared anew in media coverage of a study that compares the resource use and global warming potential of different US diets. The study,1 completed at Carnegie Mellon University, examined how energy production, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) change across three different diets: 1) a reduced-calorie plan with the same mix of food as the average US diet; 2) a USDA-recommended food mix without reducing the total calories of an average diet; and 3) reducing calories AND shifting to a USDA-recommended food mix.

So did the study find that particular foods in some diets contribute more to resource use and emissions? Yes, and the results are quite interesting! But, from the headlines of some science communication websites, you would think that the results countered all previous scientific trends that vegetarian diets reduce greenhouse gas emissions. "Lettuce produces more greenhouse gas emissions than bacon does" stated a headline for a post on Scientific American's website. IFLScience first proclaimed "Study claims being vegetarian is WORSE..." before replacing it with the milder "How some healthy foods can be bad for the environment" after (I assume) they received negative feedback. These are sites I admire and read regularly, which just goes to show how tricky it can be sometimes to find the balance between using an enticing hook and accurately portraying the scientific content. Even the original Carnegie Mellon press release grabs reader attention with "Vegetarian and 'healthy diets' could be more harmful to the environment," which was likely the source for similar connotations in other stories. These initial summaries provided unfortunate links for websites with stronger biases, such as Right Wing News, which claimed that "...being vegetarian is WORSE for the environment than eating meat." This is just flat-out wrong, as we'll see.

Did the research study really find such stark results that vegetarian diets hurt the environment to a greater degree than eating meat? Did the study find evidence to counter many previous studies claiming that vegetarian diets reduce emissions?2-4 No, but the authors did reveal some interesting trends about which foods contribute more to energy use and emissions that should inform policy. The study is fascinating in its own right and I don't believe it needs a misleading title comparing lettuce and bacon (which we will see is not a very useful comparison) to draw readership. I should note, to their credit, that some of the links I mentioned above do describe the study with more nuance in the body of the text, such as the Scientific American post. Still, simplified or sensationalist headlines that miss the underlying complexity swerve dangerously close to missing the point and grip us with their emotional intensity. Unfortunately, it is usually these emotional reactions that stay with us, drowning out the important details that will matter when deciding how to create policy or choose sustainable, healthy lifestyles. So let's talk about what the study actually discovered.

What should we eat?

The USDA released its dietary guidelines in 2010 to fight the US obesity epidemic. These recommendations, which would reduce the average caloric intake per day from 3600 to 3300 Calories, argued for reduced meat consumption and a huge increase in fish and fruit in American diets. These guidelines only focused on human health, however, and their effects on energy or water consumption as well as GHG emissions have never been studied. Thus, the goal of the study was to understand the environmental impact of healthy diets recommended by the USDA. I'll point out from the start that vegetarianism was never mentioned in the paper until the final paragraphs. So this is a paper about the relationship between USDA-defined healthy eating and sustainability, not vegetarianism.

The study outlined three diet scenarios, which I briefly outlined above: the reduced-calorie diet, which reduces daily intake by 300 Calories (Scenario 1), the USDA-recommended food mix with an unchanged daily caloric intake (Scenario 2), and a combined, reduced-calorie and USDA-recommended food mix (Scenario 3). Information about caloric intake came from USDA data, and information about resource use came from a detailed review of previous literature and policy reports.

The results of the comparison between scenarios are quite surprising at first glance. Compared to the current US diet, Scenario 1 leads to a 10% reduction in energy use, water use, and emissions. This can be straightforwardly explained by the fact that less calories means less food and thus less resources required to grow said food. However, shifting to the USDA-recommended food mix (Scenario 2) leads to a significant increase in energy (43%), water (16%), and emissions (11%). Even when combining this with reducing calories (Scenario 3), significant increases are still predicted (energy: 38%, water: 10%, emissions: 6%).

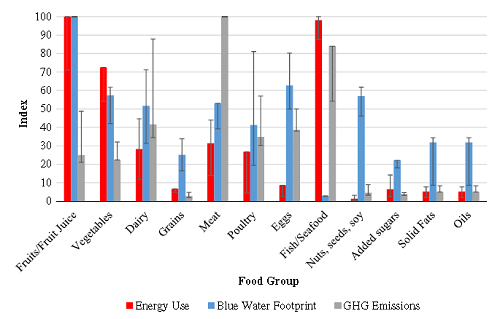

What foods did the USDA guidelines emphasize to cause these jumps in energy use, water consumption, and GHG emissions? Fruit, fish, and dairy are the major culprits. The figure to the right shows how caloric consumption changes with each scenario compared to the current average diet. As shown by the orange and green bars, the USDA recommendations de-emphasize sugars, fats, oils, and meat, while heavily promoting fruit, vegetables, and dairy.

It turns out that these shifts correlate fairly well with those foods that require the most energy and water per calorie. As seen in the next figure below, fruit, vegetables, and fish require the most energy per calorie (red bars). In addition, fish and dairy create substantial GHG emissions (grey bars). Fruit in the US has a large footprint mainly due to its production in dry climates not well-suited to support it, especially in California. This mismatch demands huge amounts of irrigation, which is both energy- and water-intensive. Fish has such a large footprint due to feed production, similar to meat, as well as the fuel used to travel to ocean regions holding the largest concentrations of fish.

In contrast, added sugars, fats, oils, and grains all require few resources and create less emissions per calorie. Since the USDA recommendations reduce the caloric intake in most of these categories, the net effect is an overall increase in all three measures of environmental impact.

Let's digest these results for a moment. Healthier diets, as defined by the USDA, have greater environmental impact because of the huge emphasis on fruits and fish. I would suggest that these results demonstrate ineffective US agricultural policy than a critique of vegetarian eating. Let's see how.

We must remember that the comparisons shown in these figures are of energy use, water use, and emissions per calorie. Yes, lettuce contributes more greenhouse gas emissions than meat per calorie, but I don't think anyone would recommend constructing a diet where we get the majority of our calories from lettuce. In fact, these results highlight the fact that the USDA has perhaps swung too far in the direction of fruits and vegetables to compensate for the obesity epidemic, suggesting an 85% increase in fruit consumption while suggesting only a small increase in grains or nuts. The latter two food groups are excellent sources of calories and protein that have much lower resource use per calorie and should be a staple in any balanced diet.

Second, emissions per calorie from meat are extremely high, so these results do not suggest that meat consumption is actually better than alternatives, but rather that other food can also have negative environmental impacts. This is a signal to intentionally develop policy that promotes smart meat alternatives. Also, emissions from meat are due to methane emissions from fertilizer production as well as all the energy required to produce feed. It's difficult to get around these sources of energy use and emissions. In contrast, environmental impacts of fruit and vegetables are largely location-dependent and due to inefficient farming practices that can be improved.

Finally, other studies in Europe and Croatia have demonstrated that healthy diet recommendations that reduce meat consumption would indeed lead to reductions in energy use, water use, and GHG emissions.5-6 This contradiction with the present study is mainly due to the difference between USDA guidelines and those used in other countries. In Germany and Europe, guidelines recommend reduced meat consumption, but do not replace it with increased dairy and fruit to the same degree as the USDA. Instead, they recommend greater amounts of oils, fats, and grains, which all use significantly reduced resources per Calorie and can still be part of a healthy diet. Again, the issue at stake is the improvement of US dietary policy to take into account sustainability.

A matter of policy

These are extremely important results, as they highlight the fact that public health must include not only the vitality of an individual but also extend to the sustainability of food production. As an alternative to meat, which has consistently and clearly been shown to be one of the most significant contributors to GHG emissions, we must develop a scientifically informed and intentional dietary guideline that takes into account resource use. Fish is not the best protein source, in this regard, but rather nuts and soybeans, for example. Grains are an excellent source of calories that must be encouraged rather than demonized in US dietary culture.

This is a discussion of public health policy, not vegetarian lifestyles. In fact, vegetarianism is only mentioned in the final paragraph of the paper to state that the "results of...studies demonstrate that adopting a vegetarian diet or even reducing meat consumption by 50% is more effective in reducing energy use, the blue water footprint, and GHG emissions...than adopting a healthier diet based on regional dietary guidelines."1 This makes sense in light of the current results - vegetarian diets include no fish, and likely utilize more grains, nuts, and soy. Anecdotally, most vegetarians I know (myself included) do not eat as much fruit as the USDA guidelines encourage. Once again, this is a USDA policy issue.

The misleading titles in popular science media, then, suggest a conflation of vegetarianism and healthy diets. There are many healthy diets, but not all are environmentally friendly nor vegetarian. The USDA guidelines likely are helpful for individual health, but clearly need to be revamped to account for the health of the planet. Vegetarian diets, if adopted mindfully, likely can fulfill both of these needs.

Accurate discussion of scientific findings is a crucial cog in the public awareness machine to promote how science can help society. When popular reports declare a new battery will begin the electric car revolution, people begin waiting for those $15,000, 300-mile-range, oil-free cars to appear on the road. When no such car appears, people usually attribute the inaccurate prediction to poor science, not media hyperbole, and lose a little faith in the scientific process. Built up over time, the concern is that this shift in attitude will have downstream effects on policy development and political beliefs (for more on this topic, a recent book by Vaclav Smil delves into some detail about the importance of accurate predictions relating to science public relations).

Regarding the present study, a friend already told me about acquaintances on Facebook declaring this study as proof that vegetarian diets are not better than eating meat, their evidence taken solely form the headlines offered by popular science websites. Such misinterpretations of fact only slow down the progress we need to improve our relationship with the Earth and find a way to live peacefully under its watch.

Scientists can be wrong. Part of the process is to replicate results, and if a finding is unrepeatable, to understand why and move a little closer to the truth. But missteps on the road to understanding are different than exaggeration. And while I'm sure I have overstepped this line over the course of my own blogging, I hope to always honor the scientific essence behind each word I write.

References

Toms, M.S. et al. "Energy use, blue water footprint, and greenhouse gas emissions for current food consumption patterns and dietary recommendations in the US." Environ Syst Decis, published online November 24 2015.

Scarborough, P. et al. "Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK." Climatic Change, 125(2): 179-192, 2014.

Green, R. et al. "The potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the UK through healthy and realistic dietary change." Climatic Change, 129(1): 253-265, 2015.

Joyce, A. et al. "The impact of nutritional choices on global warming and policy implications: examining the link between dietary choices and greenhouse gas emissions." Energy and Emission Control Technologies, 2, 33-43, 2014.

Meier, T. and Christen, O. "Environmental impacts of dietary recommendations and dietary styles: Germany as an example." Environ Sci Technol, 47(2): 877-888, 2013.

Vanham, D. et al. "The water footprint of the EU for different diets." Ecol Ind, 32:1-8, 2013.

Photo Credit

Figure of apple trees courtesy of Stephen Craven via Wikipedia

Figures of caloric changes and resource consumption per Calorie courtesy of Reference 1