Editor’s Note (10/2/17): Seventeen years before the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine went to three U.S. scientists for their research on biological clocks, one of them, Michael W. Young, set out an account in Scientific American describing the genetic studies that identified the “molecular timepieces” that are ubiquitous throughout the animal kingdom. If you are interested in understanding the biology of circadian rhythms—who hasn’t suffered from jet lag?—Young provides here perhaps the most compelling—and accessible—story to be found anywhere of how these studies unfolded. Please read this lucid description of the hunt for molecular clocks that Scientific American brought to you the better part of two decades before the three researchers confront jet lag on their trip to Stockholm.

You have to fight the urge to fall asleep at 7:00 in the evening. You are ravenous at 3 P.M. but have no appetite when suppertime rolls around. You wake up at 4:00 in the morning and cannot get back to sleep. This scenario is familiar to many people who have flown from the East Coast of the U.S. to California, a trip that entails jumping a three-hour time difference. During a weeklong business trip or vacation, your body no sooner acclimatizes to the new schedule than it is time to return home again, where you must get used to the old routine once more. Nearly every day my colleagues and I put a batch of Drosophila fruit flies through the jet lag of a simulated trip from New York to San Francisco or back. We have several refrigerator-size incubators in the laboratory: one labeled New York and another tagged San Francisco. Lights inside these incubators go on and off as the sun rises and sets in those two cities. (For consistency, we schedule sunup at 6 A.M. and sundown at 6 P.M. for both locations.) The temperature in the two incubators is a constant, balmy 77 degrees Fahrenheit.

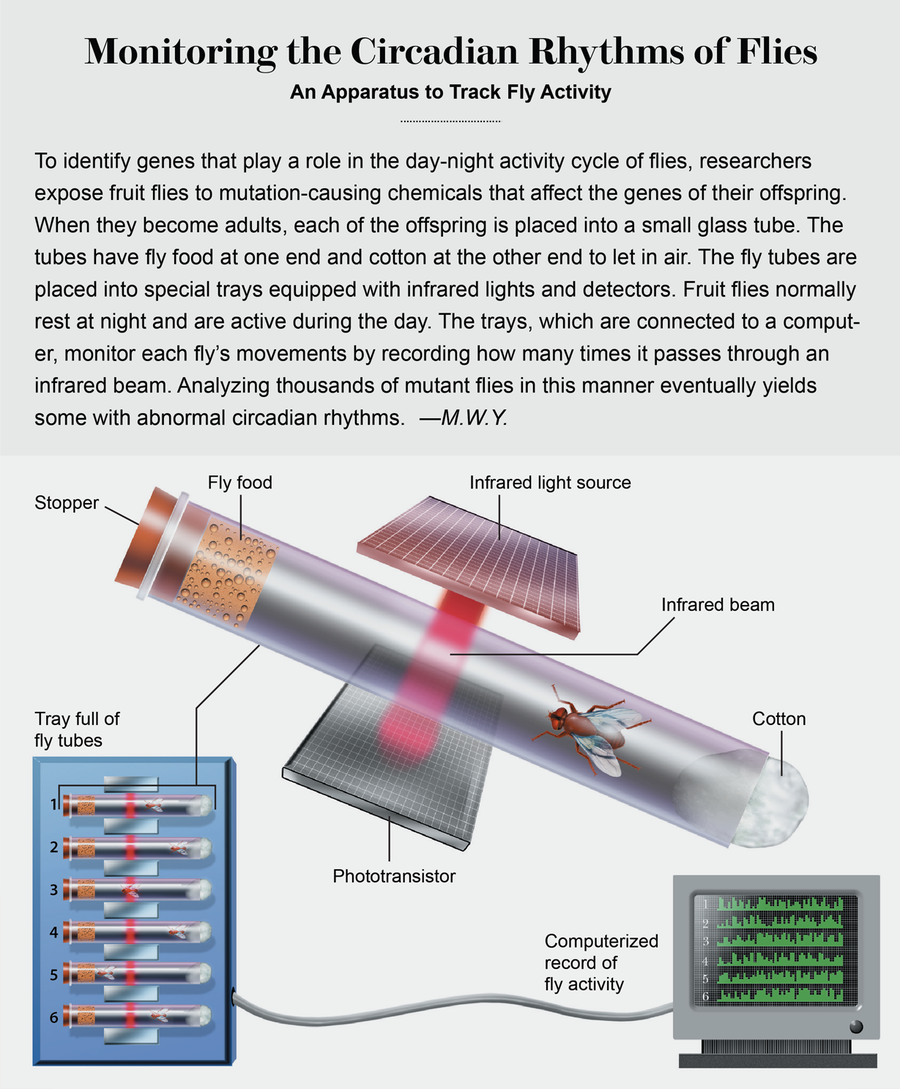

The flies take their simulated journey inside small glass tubes packed into special trays that monitor their movements with a narrow beam of infrared light. Each time a fly moves into the beam, it casts a shadow on a phototransistor in the tray, which is connected to a computer that records the activity. Going from New York to San Francisco time does not involve a five-hour flight for our flies: we simply disconnect a fly-filled tray in one incubator, move it to the other one and plug it in.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

We have used our transcontinental express to identify and study the functions of several genes that appear to be the very cogs and wheels in the works of the biological clock that controls the day-night cycles of a wide range of organisms that includes not only fruit flies but mice and humans as well. Identifying the genes allows us to determine the proteins they encode—proteins that might serve as targets for therapies for a wide range of disorders, from sleep disturbances to seasonal depression.

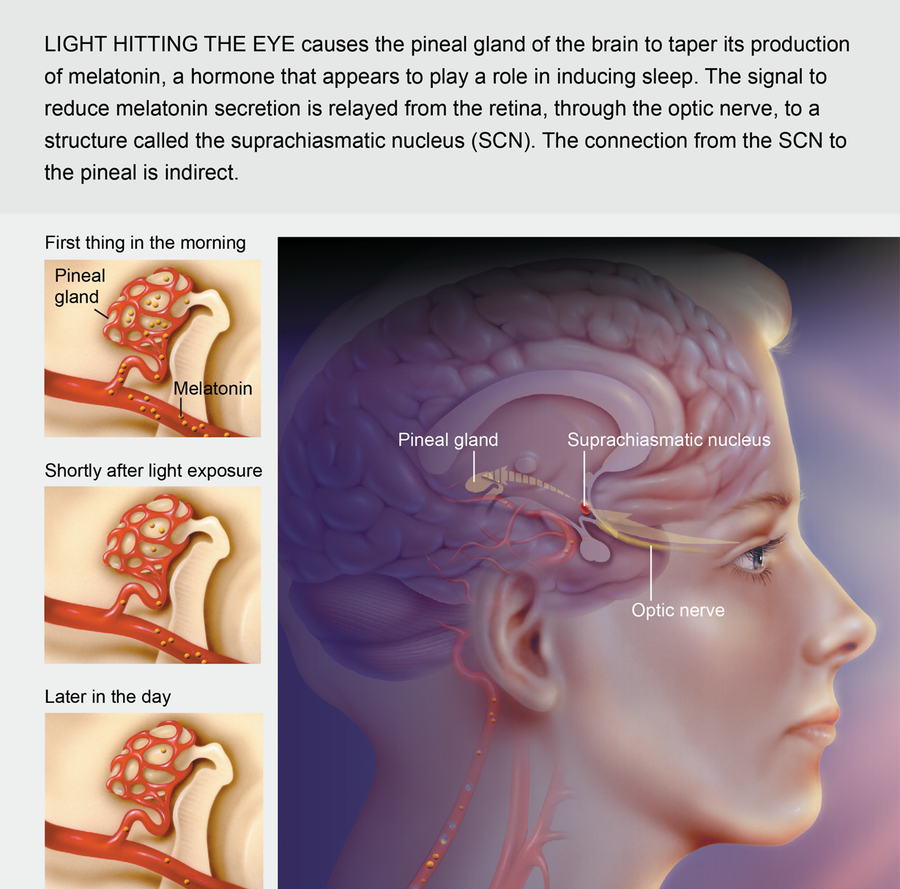

The main cog in the human biological clock is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a group of nerve cells in a region at the base of the brain called the hypothalamus. When light hits the retinas of the eyes every morning, specialized nerves send signals to the SCN, which in turn controls the production cycle of a multitude of biologically active substances. The SCN stimulates a nearby brain region called the pineal gland, for instance. According to instructions from the SCN, the pineal rhythmically produces melatonin, the so-called sleep hormone that is now available in pill form in many health-food stores. As day progresses into evening, the pineal gradually begins to make more melatonin. When blood levels of the hormone rise, there is a modest decrease in body temperature and an increased tendency to sleep.

Credit: Cynthia Turner

The Human Clock

Although light appears to reset the biological clock each day, the day-night, or circadian, rhythm continues to operate even in individuals who are deprived of light, indicating that the activity of the SCN is innate. In the early 1960s Jrgen Aschoff, then at the Max Planck Institute of Behavioral Physiology in Seewiesen, Germany, and his colleagues showed that volunteers who lived in an isolation bunker—with no natural light, clocks or other clues about time—nevertheless maintained a roughly normal sleep-wake cycle of 25 hours.

More recently Charles Czeisler, Richard E. Kronauer and their colleagues at Harvard University have determined that the human circadian rhythm is actually closer to 24 hours—24.18 hours, to be exact. The scientists studied 24 men and women ( 11 of whom were in their 20s and 13 of whom were in their 60s) who lived for more than three weeks in an environment with no time cues other than a weak cycle of light and dark that was artificially set at 28 hours and that gave the subjects their signals for bedtime.

They measured the participants' core body temperature, which normally falls at night, as well as blood concentrations of melatonin and of a stress hormone called cortisol that drops in the evening. The researchers observed that even though the subjects' days had been abnormally extended by four hours, their body temperature and melatonin and cortisol levels continued to function according to their own internal 24-hour circadian clock. What is more, age seemed to have no effect on the ticking of the clock: unlike the results of previous studies, which had suggested that aging disrupts circadian rhythms, the body-temperature and hormone fluctuations of the older subjects in the Harvard study were as regular as those of the younger group.

As informative as the bunker studies are, to investigate the genes that underlie the biological clock scientists had to turn to fruit flies. Flies are ideal for genetic studies because they have short life spans and are small, which means that researchers can breed and interbreed thousands of them in the laboratory until interesting mutations crop up. To speed up the mutation process, scientists usually expose flies to mutation-causing chemicals called mutagens.

The first fly mutants to show altered circadian rhythms were identified in the early 1970s by Ron Konopka and Seymour Benzer of the California Institute of Technology. These researchers fed a mutagen to a few fruit flies and then monitored the movement of 2,000 of the progeny, in part using a form of the same apparatus that we now use in our New York to San Francisco experiments. Most of the flies had a normal 24-hour circadian rhythm: the insects were active for roughly 12 hours a day and rested for the other 12 hours. But three of the flies had mutations that caused them to break the pattern. One had a 19-hour cycle, one had a 28-hour cycle, and the third fly appeared to have no circadian rhythm at all, resting and becoming active seemingly at random.

Time Flies

In 1986 my research group at the Rockefeller University and another led by Jeffrey Hall of Brandeis University and Michael Rosbash of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Brandeis found that the three mutant flies had three different alterations in a single gene named period, or per, which each of our teams had independently isolated two years earlier. Because different mutations in the same gene caused the three behaviors, we concluded that per is somehow actively involved both in producing circadian rhythm in flies and in setting the rhythm's pace.

After isolating per, we began to question whether the gene acted alone in controlling the day-night cycle. To find out, two postdoctoral fellows in my laboratory, Amita Sehgal and Jeffrey Price, screened more than 7,000 flies to see if they could identify other rhythm mutants. They finally found a fly that, like one of the per mutants, had no apparent circadian rhythm. The new mutation turned out to be on chromosome 2, whereas per had been mapped to the X chromosome. We knew this had to be a new gene, and we named it timeless, or tim.

Credit: Cynthia Turner

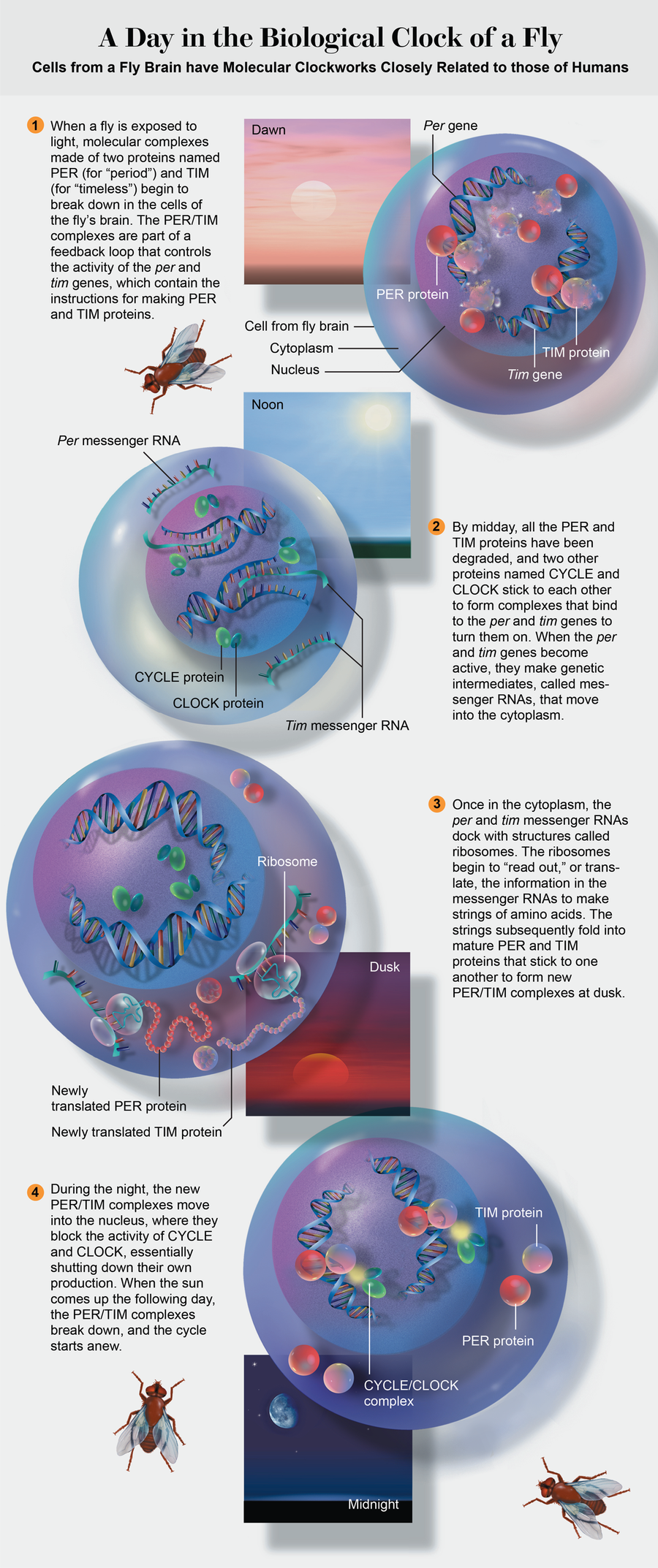

But how did the new gene relate to per? Genes are made of DNA, which contains the instructions for making proteins. DNA never leaves the nucleus of the cell; its molecular recipes are read out in the form of messenger RNA, which leaves the nucleus and enters the cytoplasm, where proteins are made. We used the tim and per genes to make PER and TIM proteins in the laboratory. In collaboration with Charles Weitz of Harvard Medical School, we observed that when we mixed the two proteins, they stuck to each other, suggesting that they might interact within cells.

In a series of experiments, we found that the production of PER and TIM proteins involves a clocklike feedback loop see illustration at left. The per and tim genes are active until concentrations of their proteins become high enough that the two begin to bind to each other. When they do, they form complexes that enter the nucleus and shut down the genes that made them. After a few hours enzymes degrade the complexes, the genes start up again, and the cycle begins a new.

Moving the Hands of Time

Once we had found two genes that functioned in concert to make a molecular clock, we began to wonder how the clock could be reset. After all, our sleep-wake cycles fully adapt to travel across any number of time zones, even though the adjustment might take a couple of days or weeks.

That is when we began to shuttle trays of flies back and forth between the New York and San Francisco incubators. One of the first things we and others noticed was that whenever a fly was moved from a darkened incubator to one that was brightly lit to mimic day- light, the TIM proteins in the fly's brain disappeared—in a matter of minutes.

Even more interestingly, we noted that the direction the flies traveled affected the levels of their TIM proteins. If we removed flies from New York at 8 P.M. local time, when it was dark, and put them into San Francisco, where it was still light at 5 P.M. local time, their TIM levels plunged. But an hour later, when the lights went off in San Francisco, TIM began to reaccumulate. Evidently the flies' molecular clocks were initially stopped by the transfer, but after a delay they resumed ticking in the pattern of the new time zone.

In contrast, flies moved at 4 A.M. from San Francisco experienced a premature sunrise when they were placed in New York, where it was 7 A.M. This move also caused TIM levels to drop, but this time the protein did not begin to build up again because the molecular clock was advanced by the time-zone switch.

We learned more about the mechanism behind the different molecular responses by examining the timing of the production of tim RNA. Levels of tim RNA are highest at about 8 P.M. local time and lowest between 6 A.M. and 8 A.M. A fly moving at 8 P.M. from New York to San Francisco is producing maximum levels of tim RNA, so protein lost by exposure to light in San Francisco is easily replaced after sunset in the new location. A fly traveling at 4 A.M. from San Francisco to New York, however, was making very little tim RNA before departure. What the fly experiences as a premature sunrise eliminates TIM and allows the next cycle of production to begin with an earlier schedule.

Not Just Bugs

Giving flies jet lag has turned out to have direct implications for understanding circadian rhythm in mammals, including humans. In 1997 researchers led by Hajime Tei of the University of Tokyo and Hitoshi Okamura of Kobe University in Japan—and, independently, Cheng Chi Lee of Baylor College of Medicine—isolated the mouse and human equivalents of per. Another flurry of work, this time involving many laboratories, turned up mouse and human forms of tim in 1998. And the genes were active in the suprachiasmatic nucleus.

Credit: Cynthia Turner

Studies involving mice also helped to answer a key question: What turns on the activity of the per and tim genes in the first place? In 1997 Joseph Takaha-shi of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at Northwestern University and his colleagues isolated a gene they called Clock that when mutated yielded mice with no discernible circadian rhythm. The gene encodes a transcription factor, a protein that in this case binds to DNA and allows it to be read out as messenger RNA.

Shortly thereafter a fly version of the mouse Clock gene was isolated, and various research teams began to introduce combinations of the per, tim and Clock genes into mammalian and fruit fly cells. These experiments revealed that the CLOCK protein targets the per gene in mice and both the per and tim genes in flies. The system had come full circle: in flies, whose clocks are the best understood, the CLOCK protein—in combination with a protein encoded by a gene called cycle— binds to and activates the per and tim genes, but only if no PER and TIM proteins are present in the nucleus. These four genes and their proteins constitute the heart of the biological clock in flies, and with some modifications they appear to form a mechanism governing circadian rhythms throughout the animal kingdom, from fish to frogs, mice to humans.

Recently Steve Reppert's group at Harvard and Justin Blau in my laboratory have begun to explore the specific signals connecting the mouse and fruit fly biological clocks to the timing of various behaviors, hormone fluctuations and other functions. It seems that some output genes are turned on by a direct interaction with the CLOCK protein. PER and TIM block the ability of CLOCK to turn on these genes at the same time as they are producing the oscillations of the central feedback loop— setting up extended patterns of cycling gene activity.

An exciting prospect for the future involves the recovery of an entire system of clock-regulated genes in organisms such as fruit flies and mice. It is likely that previously uncharacterized gene products with intriguing effects on behavior will be discovered within these networks. Perhaps one of these, or a component of the molecular clock itself, will become a favored target for drugs to relieve jet lag, the side effects of shift work, or sleep disorders and related depressive illnesses. Adjusting to a trip from New York to San Francisco might one day be much easier.

THE BIOLOGICAL CLOCK

The author answers some key questions

Where is the biological clock? In mammals the master clock that dictates the day-night cycle of activity known as circadian rhythm resides in a part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). But cells elsewhere also show clock activity.

What drives the clock? Within individual SCN cells, specialized clock genes are switched on and off by the proteins they encode in a feedback loop that has a 24-hour rhythm.

Is the biological clock dependent on the normal 24-hour cycle of light and darkness? No. The molecular rhythms of clock-gene activity are innate and self-sustaining. They persist in the absence of environmental cycles of day and night.

What role does light play in regulating and resetting the biological clock? Bright light absorbed by the retina during the day helps to synchronize the rhythms of activity of the clock genes to the prevailing environmental cycle. Exposure to bright light at night resets circadian rhythms by acutely changing the amount of some clock-gene products.

How does the molecular clock regulate an individual's day-night activity? The fluctuating proteins synthesized by clock genes control additional genetic pathways that connect the molecular clock to timed changes in an animal's physiology and behavior.

CLOCKS EVERYWHERE

They are not just in the brain

Most of the research on the biological clocks of animals has focused on the brain, but that is not the only organ that observes a day-night rhythm.

Jadwiga Giebultowicz of Oregon State University has identified PER and TIM proteins—key components of biological clocks—in the kidney like malpighian tubules of fruit flies. She has also observed that the proteins are produced according to a circadian cycle, rising at night and falling during the day. The cycle persists even in decapitated flies, demonstrating that the malpighian cells are not merely responding to signals from the insects'brains.

In addition, Steve Kay's research group at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jol-la, Calif., has uncovered evidence of biological clocks in the wings, legs, oral regions and antennae of fruit flies. By transferring genes that direct the production of fluorescent PER proteins into living flies, Kay and his colleagues have shown that each tissue carries an independent, photoreceptive clock. The clocks even continue to function and respond to light when each tissue is dissected from the insect.

And the extracranial biological clocks are not restricted to fruit flies. Ueli Schibler of the University of Geneva showed in 1998 that the per genes of rat connective-tissue cells called fibroblasts are active according to a circadian cycle.

The diversity of the various cell types displaying circadian clock activity suggests that for many tissues correct timing is important enough to warrant keeping track of it locally. The findings might give new meaning to the term body clock. — M.W.Y.