On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

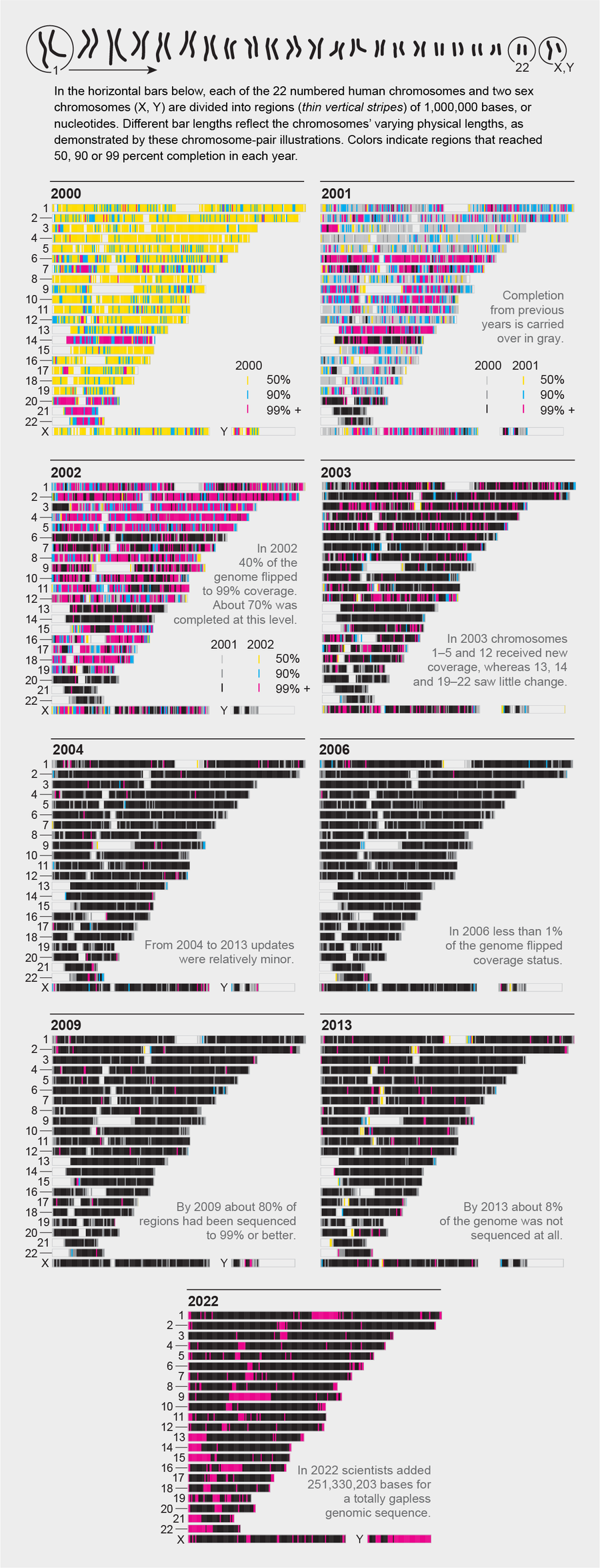

The human genome is at last complete. Researchers have been working for decades toward this goal, and the Human Genome Project claimed victory in 2001, when it had read almost all of a person's DNA. But the stubborn remaining 8 percent of the genome took another two decades to decipher. These final sections were highly repetitive and highly variable among individuals, making them the hardest parts to sequence. Yet they revealed hundreds of new genes, including genes involved in immune responses and those responsible for humans developing larger brains than our primate ancestors. “Now that we have one complete reference, we can understand human variation and how we changed with respect to our closest related species on the planet,” says geneticist Evan Eichler of the University of Washington, one of the co-chairs of the Telomere-to-Telomere consortium that finished the genome.

Credit: Martin Krzywinski; Sources: UCSC Genome Browser; “The Complete Sequence of a Human Genome,” by Sergey Nurk et al., in Science, Vol. 376; April 2022

Editor’s Note (7/22/22): The graphic in this article was edited after posting to correct the number of bases in a totally gapless genomic sequence in 2022.