Abstract

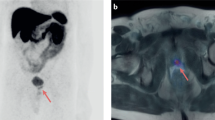

Prostate cancer poses a major public health problem, particularly in the US and Europe, where it constitutes the most common type of malignancy among men, excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers. The disease is characterized by a wide spectrum of biological and clinical phenotypes, and its evaluation by imaging remains a challenge in view of this heterogeneity. Imaging in prostate cancer can be used in the initial diagnosis of the primary tumor, to determine the occurrence and extent of any extracapsular spread, for guidance in delivery and evaluation of local therapy in organ-confined disease, in locoregional lymph node staging, to detect locally recurrent and metastatic disease in biochemical relapse, to predict and assess tumor response to systemic therapy or salvage therapy, and in disease prognostication (in terms of the length of time taken for castrate-sensitive disease to become refractory to hormones and overall patient survival). Evidence from animal-based translational and human-based clinical studies points to a potential and emerging role for PET, using F-fluorodeoxyglucose as a radiotracer, in the imaging evaluation of prostate cancer.

Key Points

-

Generally, high uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is expected in prostate tumors that are poorly differentiated, hypoxic and have a high Gleason score

-

Glucose metabolism in prostate tumors is modulated by androgen; FDG-PET can, therefore, be useful in monitoring response to androgen deprivation therapy

-

FDG-PET has limited use in diagnosis and staging of clinically organ-confined disease and can be falsely negative or falsely positive

-

FDG-PET might be useful for diagnosing and staging primary tumors, detecting locally recurrent and/or metastatic disease, assessing the extent of metabolically active castrate-resistant disease, monitoring treatment responses and in prognostication

-

Results from the NOPR show that FDG-PET influenced clinical management in 35.1% of prostate cancer cases

-

Different PET radiotracers are likely to be suited to various clinical states of prostate cancer, taking advantage of the most relevant biological markers of disease

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

SEER: The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program: Cancer of the Prostate Statistics 2008. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html.

Frank, I. N., Graham Jr, S. & Nabors, W. L. Urologic and Male Genital Cancers. In American Cancer Society Textbook of Clinical Oncology (Eds Holleb, A. I., Fink, D. J. & Murphy, G. P.) 280–283 (New York, American Cancer Society, 1991).

Kessler, B. & Albertsen, P. The natural history of prostate cancer. Urol. Clin. North Am. 30, 219–226 (2003).

Small, E. J. Prostate cancer: incidence, management and outcomes. Drugs Aging 13, 71–81 (1998).

Ploch, N. R. & Brawer, M. K. How to use prostate-specific antigen. Urology 43 (2 Suppl.), 27–35 (1994).

Lukes, M. et al. Prostate-specific antigen: current status. Folio Biol. (Praha) 47, 41–49 (2001).

Boccon-Gibod, L. Prostate-specific antigen or PSA. Facts and probabilities [French]. Presse Med. 24, 1471–1472 (1995).

Safa, A. A. et al. Undetectable serum prostate-specific antigen associated with metastatic prostate cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 323–326 (1998).

Sella, A. et al. Low PSA metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 38, 250–254 (2000).

Beardo, P. et al. Undetectable prostate specific antigen in disseminated prostate cancer. J. Urol. 166, 993 (2001).

Lofters, A. et al. “PSA-itis”: knowledge of serum prostate specific antigen and other causes of anxiety in men with metastatic prostate cancer. J. Urol. 168, 2516–2520 (2002).

Dong, J. T. et al. Prostate cancer—biology of metastasis and its clinical implications. World J. Urol. 14, 182–189 (1996).

Yu, K. K. & Hricak, H. Imaging prostate cancer. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 38, 59–85 (2000).

Yu, K. K. & Hawkins, R. A. The prostate: diagnostic evaluation of metastatic disease. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 38, 139–157 (2000).

Dotan, Z. A. Bone imaging in prostate cancer. Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol. 5, 434–444 (2008).

Fair, W. R., Israeli, R. S. & Heston, W. D. Prostate-specific membrane antigen. Prostate 32, 140–148 (1997).

Haseman, M. K., Rosenthal, S. A. & Polascik, T. J. Capromab pendetide imaging of prostate cancer. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 15, 131–140 (2000).

Harisinghani, M. G. et al. Noninvasive detection of clinically occult lymph-node metastases in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 2491–2499 (2003).

Phelps, M. E. PET: the merging of biology and imaging into molecular imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 41, 661–681 (2000).

Gambhir, S. S. Molecular imaging of cancer with positron emission tomography. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 683–693 (2002).

Basu, S. & Alavi, A. Unparalleled contribution of 18F-FDG PET to medicine over 3 decades. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 17N–21N, 37N (2008).

National Oncologic PET Registry. http://www.cancerPETregistry.org.

Hillner, B. E. et al. Impact of positron emission tomography/computed tomography and positron mission tomography (PET) alone on expected management of patients with cancer: initial results from the National Oncologic PET Registry. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 4229 (2008).

Hillner, B. E. et al. Relationship between cancer type and impact of PET and PET/CT on intended management: findings of the National Oncologic PET Registry. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 1928–1935 (2008).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100, 57–70 (2000).

Gambhir, S. S. Molecular imaging of cancer: from molecules to humans. Introduction. J. Nucl. Med. 49 (Suppl. 2), 1S–4S (2008).

Haberkorn, U. et al. FDG uptake, tumor proliferation and expression of glycolysis associated genes in animal tumor models. Nucl. Med. Biol. 21, 827–834 (1994).

Clavo, A. C., Brown, R. S. & Wahl, R. L. Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in human cancer cell lines is increased by hypoxia. J. Nucl. Med. 36, 1625–1632 (1995).

Pauwels, E. K. et al. FDG accumulation and tumor biology. Nucl. Med. Biol. 25, 317–322 (1998).

Mochizuki, T. et al. FDG uptake and glucose transporter subtype expression in experimental tumor and inflammation models. J. Nucl. Med. 42, 1551–1555 (2001).

Gillies, R. J., Robey, I. & Gatenby, R. A. Causes and consequences of increased glucose metabolism of cancers. J. Nucl. Med. 49 (6 Suppl.), 24S–42S (2008).

Plathow, C. & Weber, W. A. Tumor cell metabolism imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 49 (6 Suppl.), 43S–63S (2008).

Gatenby, R. A. & Gillies, R. J. A microenvironmental model of carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 56–61 (2008).

uman Genome Organisation (HUGO) Gene Nomenclature Committee. http://www.genenames.org.

Macheda, M. L., Rogers, S. & Bets, J. D. Molecular and cellular regulation of glucose transport (GLUT) proteins in cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 202, 654–662 (2005).

Mathupala, S. P., Ko, Y. H. & Pederson, P. L. Hexokinase II: cancer's double-edged sword acting as both facilitator and gatekeeper of malignancy when bound to mitochondria. Oncogene 25, 4777–4786 (2006).

Smith, T. A. Mammalian hexokinases and their abnormal expression in cancer. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 57, 170–178 (2000).

Caraco, C. et al. Cellular release of [18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose as a function of the glucose-6-phosphatates enzyme system. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18489–18494 (2000).

Effert, P. et al. Expression of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) in cell lines and clinical specimen from human prostate adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 24, 3057–3063 (2004).

Chandler, J. D. et al. Expression and localization of GLUT1 and GLUT12 in prostate carcinoma. Cancer 97, 2035–2042 (2003).

Stewardt, G. D. et al. Analysis of hypoxia-associated gene expression in prostate cancer: lysyl oxidase and glucose transporter 1 expression correlate with Gleason score. Oncol. Rep. 20, 1561–1567 (2008).

Hara, T., Bansal, A. & DeGrado, T. R. Effect of hypoxia on the uptake of [methyl-3H]choline, [1–14C]acetate and [18F]FDG in cultured prostate cancer cells. Nucl. Med. Biol. 33, 977–984 (2006).

Palayoor, S. T., Tofilon, P. J. & Coleman, C. N. Ibuprofen-mediated reduction of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α in prostate cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 3150–3157 (2003).

Jadvar, H. et al. Glucose metabolism of human prostate cancer mouse xenografts. Mol. Imaging 4, 91–97 (2005).

Oyama, N. et al. MicroPET assessment of androgenic control of glucose and acetate uptake in the rat prostate and a prostate cancer tumor model. Nucl. Med. Biol. 29, 783–790 (2002).

Agus, D. B. et al. Positron emission tomography of a human prostate cancer xenograft: association of changes in deoxyglucose accumulation with other measures of outcome following androgen withdrawal. Cancer Res. 58, 3009–3014 (1998).

Apolo, A. B., Pandit-Taskar, N. & Morris, M. J. Novel tracers and their development for the imaging of metastatic prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 49, 2031–2041 (2008).

Takahashi, N. et al. The roles of PET and PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. Oncology 72, 226–233 (2007).

Salminen, E. et al. Investigations with FDG-PET scanning in prostate cancer show limited value for clinical practice. Acta Oncol. 41, 425–429 (2002).

Pugachev, A. et al. Dependence of FDG uptake on tumor microenvironment. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 62, 545–553 (2005).

Etchebehere, E. C. et al. Qualitative and quantitative comparison between images obtained with filtered back projection and iterative reconstruction in prostate cancer lesions of 18F-FDG PET. Q. J. Nucl. Med. 46, 122–130 (2002).

Turlakow, A. et al. local detection of prostate cancer by positron emission tomography with 2-fluorodeoxyglucose: comparison of filtered back projection and iterative reconstruction with segmented attenuation correction. Q. J. Nucl. Med. 45, 235–244 (2001).

Vandenberghe, S. et al. Iterative reconstruction algorithms in nuclear medicine. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 25, 105–111 (2001).

Jadvar, H. et al. [F-8]-fluorodeoxyglucose PET–CT of the normal prostate gland. Ann. Nucl. Med. 22, 787–793 (2008).

Effert, P. J. et al. Metabolic imaging of untreated prostate cancer by positron emission tomography with 18fluorine-labeled deoxyglucose. J. Urol. 155, 994–998 (1996).

Hofer, C. et al. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is useless for the detection of local recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 36, 31–35 (1999).

Patel, P. et al. Evaluation of metabolic activity of prostate gland with PET–CT. J. Nucl. Med. 43 (5 Suppl.), 119P (2002).

von Mallek, D. et al. Technical limits of PET/CT with 18FDG in prostate cancer [German]. Aktuelle Urol. 37, 218–221 (2006).

Liu, I. J. et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography studies in diagnosis and staging of clinically organ-confined prostate cancer. Urology 57, 108–111 (2001).

Kao, P. F., Chou, Y. H. & Lai, C. W. Diffuse FDG uptake in acute prostatitis. Clin. Nucl. Med. 33, 308–310 (2008).

Oyama, N. et al. The increased accumulation of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose in untreated prostate cancer. Jpn J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 623–629 (1999).

Kanamaru, H. et al. Evaluation of prostate cancer using FDG-PET [Japanese]. Hinyokika Kiyo 46, 851–853 (2000).

Lucignani, G., Paganelli, G. & Bombardieri, E. The use of standardized uptake values for assessing FDG uptake with PET in oncology: a clinical perspective. Nucl. Med. Commun. 25, 651–656 (2004).

Shreve, P. D. et al. Metastatic prostate cancer: initial findings of PET with FDG. Radiology 199, 751–756 (1996).

Morris, N. J. et al. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology 59, 913–918 (2002).

Yeh, S. D. et al. Detection of bony metastases of androgen-independent prostate cancer by PET-FDG. Nucl. Med. Biol. 23, 693–697 (1996).

Jadvar, H., Pinski, J. & Conti, P. FDG PET in suspected recurrent and metastatic prostate cancer. Oncol. Rep. 10, 1485–1488 (2003).

Jadvar, H. et al. Concordance among FDG PET, CT and bone scan in men with metastatic prostate cancer. Presented at the 55th Annual Meeting of the Society of Nuclear Medicine, 2008 June 15–19, New Orleans, LA.

Chang, C. H. et al. Detecting metastatic pelvic lymph nodes by (18)F-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with prostate-specific antigen relapse after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Urol. Int. 70, 311–315 (2003).

Schoder, H. et al. 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography for detection of disease in patients with prostate-specific antigen relapse after radical prostatectomy. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 4761–4769 (2005).

Sanz, G. et al. Positron emission tomography with 18fluorine-labelled deoxyglucose: utility in localized and advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 84, 1028–1031 (1999).

Sung, J. et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography studies in the diagnosis and staging of clinically advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 92, 24–27 (2003).

Seltzer, M. A. et al. Comparison of helical computerized tomography, positron emission tomography and monoclonal antibody scans for evaluation of lymph node metastases in patients with prostate specific antigen relapse after treatment for localized prostate cancer. J. Urol. 162, 1322–1328 (1999).

Oyama, N. et al. FDG PET for evaluating the change of glucose metabolism in prostate cancer after androgen ablation. Nucl. Med. Commun. 22, 963–969 (2001).

Zhang, Y. et al. Longitudinally quantitative 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose micro positron emission tomography imaging for efficacy of new anticancer drugs: a case study with bortezomib in prostate cancer murine model. Mol. Imaging Biol. 8, 300–308 (2006).

Haberkorn, U. et al. PET 2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose uptake in rat prostate adenocarcinoma during chemotherapy with gemcitabine. J. Nucl. Med. 38, 1215–1221 (1997).

Morris, M. J. et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as an outcome measure for castrate metastatic prostate cancer treated with antimicrotubule chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 3210–3216 (2005).

Oyama, N. et al. Prognostic value of 2-deoxy-2-[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography imaging for patients with prostate cancer. Mol. Imaging Biol. 4, 99–104 (2002).

Farsad, M. et al. Positron-emission tomography in imaging and staging prostate cancer. Cancer Biomark. 4, 277–284 (2008).

Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss, A. & Strauss, L. G. PET imaging of prostate cancer with 11C-acetate. J. Nucl. Med. 44, 556–558 (2003).

Reske, S. N. et al. Imaging prostate cancer with 11C-choline PET/CT. J. Nucl. Med. 47, 1249–1254 (2006).

Nunez, R. et al. Combined 18F-FDG and C-11 methionine PET scans in patients with newly progressive metastatic prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 43, 46–55 (2002).

Larson, S. M. et al. Tumor localization of 16β-18F-fluoro-5α-dihydrotestosterone versus 18F-FDG in patients with progressive, metastatic prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 45, 366–373 (2004).

Schuster, D. M. et al. Initial experience with radiotracer anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid with PET/CT in prostate carcinoma. J. Nucl. Med. 48, 56–63 (2007).

Mease, R. C. et al. N-[N-[(S)-1, 3-Dicarboxypropyl]carbamoyl]-4-[18F]fluorobenzyl-l-cysteine, [18F]DCFBC: a new imaging probe for prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 3036–3043 (2008).

Even-Sapir, E. et al. The detection of bone metastases in patients with high risk prostate cancer:99mTc-MDP planar bone scintigraphy, single- and multi-filed-of-view SPECT, 18F-fluoride PET, and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J. Nucl. Med. 47, 287–297 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Cancer Institute Grant R01-CA111613).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jadvar, H. Molecular imaging of prostate cancer with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET. Nat Rev Urol 6, 317–323 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2009.81

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2009.81

This article is cited by

-

Using PSMA imaging for prognostication in localized and advanced prostate cancer

Nature Reviews Urology (2023)

-

Role of volumetric parameters obtained from 68 Ga-PSMA PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT in predicting overall survival in patients with mCRPC receiving taxane therapy

Annals of Nuclear Medicine (2023)

-

Value of 68Ga-labeled bombesin antagonist (RM2) in the detection of primary prostate cancer comparing with [18F]fluoromethylcholine PET-CT and multiparametric MRI—a phase I/II study

European Radiology (2022)

-

Simultaneous PET/MRI in the Evaluation of Breast and Prostate Cancer Using Combined Na[18F] F and [18F]FDG: a Focus on Skeletal Lesions

Molecular Imaging and Biology (2020)

-

PET imaging for lymph node dissection in prostate cancer

World Journal of Urology (2017)