Key Points

-

Prions represent a new class of infectious agents which propagate on a protein-only level, not requiring agent-encoded nucleic acids.

-

Newly emergent prion diseases such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), and chronic wasting disease are a source of critical concern to physicians, veterinarians, economists, politicians — and the general public.

-

Numerous strategies and targets have been proposed for the immunotherapy of prion diseases, based on the necessity of agent replication in lymphoid tissue prion to neuro-invasion, and the sensitivity of prion propagation to antibodies in vitro.

-

Prion replication in cell lines in vitro is sensitive to antibodies directed against the normal and abnormal isoforms of the prion protein.

-

Numerous strategies and potential targets for treating transmissible spongiform encephalopathies have been suggested, with the most studied target being the inhibition of PrPSc accumulation.

-

The development of higher-throughput screening assays based on scrapie-infected cell cultures have been developed and have greatly accelerated the pace of discovery of PrPSc inhibitors.

-

Several classes of inhibitors of PrPSc formation have been identified, some of which show prophylactic activity against scrapie in rodents. However, chemotherapeutic treatments of clinically affected scrapie-infected rodents and CJD-infected humans have been largely ineffectual.

-

Compounds that destabilize PrPSc and/or reduce scrapie infectivity have been identified that could be useful as decontaminants.

-

The most effective therapeutic strategies might require not only the inhibition of PrPSc formation but also the reversal of TSE-associated neuropathology.

Abstract

The transmissible spongiform encephalopathies could represent a new mode of transmission for infectious diseases — a process more akin to crystallization than to microbial replication. The prion hypothesis proposes that the normal isoform of the prion protein is converted to a disease-specific species by template-directed misfolding. Therapeutic and prophylactic strategies to combat these diseases have emerged from immunological and chemotherapeutic approaches. The lessons learned in treating prion disease will almost certainly have an impact on other diseases that are characterized by the pathological accumulation of misfolded proteins.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Will, R. G. et al. A new variant of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in the UK. Lancet 347, 921–925 (1996). The first recognition of a surprising zoonosis: bovine spongiform encephalopathy to human beings.

Coulthart, M. B. & Cashman, N. R. Variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease: a summary of current scientific knowledge in relation to public health. CMAJ 165, 51–58 (2001).

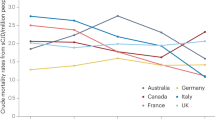

Ghani, A. C., Donnelly, C. A., Ferguson, N. M. & Anderson, R. M. Updated projections of future vCJD deaths in the UK. BMC Infect. Dis. 3, 4 (2003).

Llewelyn, C. A. et al. G. Possible transmission of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease by blood transfusion. Lancet 363, 417–421 (2004). The second description of blood borne transmission of any human prion disease, on a well-recognized background of iatrogenic transmission through prion-contaminated growth hormone, dura, corneas, and neurosurgical instrumentation.

Collins, S. J. et al. Quinacrine does not prolong survival in a murine Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease model. Ann. Neurol. 52, 503–506 (2002).

Wadsworth, J. D. et al. Tissue distribution of protease resistant prion protein in variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease using a highly sensitive immunoblotting assay. Lancet 358, 171–180 (2001).

Bruce, M. E. et al. Transmissions to mice indicate that 'new variant' CJD is caused by the BSE agent. Nature 389, 498–501 (1997).

Hill, A. F. et al. The same prion strain causes vCJD and BSE. Nature 389, 448–450 (1997).

Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: BSE webpage [online], <http://www.defra.gov.uk/animalh/bse/index.html> (2004).

Donnelly, C. A., Ferguson, N. M., Ghani, A. C. & Anderson, R. M. Implications of BSE infection screening data for the scale of the British BSE epidemic and current European infection levels. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 269, 2179–2190 (2002).

Schreuder, B. E. & Somerville, R. A. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy in sheep? Rev. Sci. Tech. 22, 103–120 (2003).

Baylis, M. et al. BSE — a wolf in sheep's clothing. Trends Microbiol. 10, 563–570 (2002).

Houston, F. et al. Prion diseases: BSE in sheep bred for resistance to infection. Nature 423, 498 (2003).

Williams, E. S. & Young, S. Chronic wasting disease of captive mule deer: a spongiform encephalopathy. J. Wildl. Dis. 16, 89–98 (1980).

Brown, P. & Bradley, R. 1755 and all that: a historical primer of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. BMJ 317, 1688–1692 (1998).

Belay, E. D. et al. Chronic wasting disease and potential transmission to humans. Emerging Infect. Dis. 10, (2004).

Riesner, D. et al. Prions and nucleic acids: search for 'residual' nucleic acids and screening for mutations in the PrP-gene. Dev. Biol. Stand. 80, 173–181 (1993).

Griffith, J. S. Self-replication and scrapie. Nature 215, 1043–1044 (1967). The first proposal of plausible mechanisms by which TSE agents (now called prions) could replicate as infectious proteins. The featured mechanisms are surprisingly close to those favored today; that is, the pathological agent was proposed to be an abnormal oligomeric state of a host protein that templates, autocatalyses or nucleates post-translational conformational changes in its normal counterpart.

Prusiner, S. B. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science 216, 136–144 (1982). This article was the first coin to the term 'prions' for the TSE infectious agents, and forcefully rekindles the argument that these agents form a novel class of pathogen that is devoid of nucleic acids. The protein-only mechanisms proposed here for prion replication were reverse translation, protein-directed protein synthesis and protein-directed alteration of prion protein gene expression, none of which seem to be applicable today.

Prusiner, S. B. Prions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13363–13383 (1998).

Brown, P., Goldfarb, L. G. & Gajdusek, D. C. The new biology of spongiform encephalopathy: infectious amyloidoses with a genetic twist. Lancet 337, 1019–1022 (1991).

Caughey, B. W. et al. Secondary structure analysis of the scrapie-associated protein PrP 27-30 in water by infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry 30, 7672–7680 (1991). The first study revealing high β-sheet content in infectious preparations of PrPSc.

Safar, J., Roller, P. P., Gajdusek, D. C. & Gibbs, C. J. Jr. Conformational transitions, dissociation, and unfolding of scrapie amyloid (prion) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 20276–20284 (1993).

Pan, K. -M. et al. Conversion of α-helices into β-sheets features in the formation of the scrapie prion protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 10962–10966 (1993). The first study showing high α-helical content of PrPC, providing evidence that conformational change in PrPC is important in its conversion to PrPSc.

Riek, R., Hornemann, S., Wider, G., Glockshuber, R. & Wuthrich, K. NMR characterization of the full-length recombinant murine prion protein, mPrP(23-21). FEBS Lett. 413, 282–288 (1997). The first glimpse of the full-length normal prion protein at atomic resolution. Follows the first determination of the three-dimensional structure of a PrP fragment by the same groups.

Oesch, B. et al. A cellular gene encodes scrapie PrP 27–30 protein. Cell 40, 735–746 (1985).

Meyer, R. K. et al. Separation and properties of cellular and scrapie prion protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 83, 2310–2314 (1986).

Caughey, B., Race, R. E. & Chesebro, B. Detection of prion protein mRNA in normal and scrapie-infected tissues and cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 69, 711–716 (1988).

Bendheim, P. E. et al. Nearly ubiquitous tissue distribution of the scrapie agent precursor protein. Neurology 42, 149–156 (1992).

Prusiner, S. B. Molecular biology of prion diseases. Science 252, 1515–1522 (1991).

Come, J. H., Fraser, P. E. & Lansbury, P. T. Jr. A kinetic model for amyloid formation in the prion diseases: importance of seeding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 5959–5963 (1993).

Kocisko, D. A. et al. Cell-free formation of protease-resistant prion protein. Nature 370, 471–474 (1994).

Bessen, R. A. et al. Nongenetic propagation of strain-specific phenotypes of scrapie prion protein. Nature 375, 698–700 (1995).

Caughey, B. et al. Interactions and conversions of prion protein isoforms. Adv. Protein Chem. 57, 139–169 (2001).

Saborio, G. P., Permanne, B. & Soto, C. Sensitive detection of pathological prion protein by cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. Nature 411, 810–813 (2001).

Hill, A. F., Antoniou, M. & Collinge, J. Protease-resistant prion protein produced in vitro lacks detectable infectivity. J. Gen. Virol. 80, 11–14 (1999).

Bessen, R. A. & Marsh, R. F. Distinct PrP properties suggest the molecular basis of strain variation in transmissible mink encephalopathy. J. Virol. 68, 7859–7868 (1994).

Lasmezas, C. I. et al. Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science 275, 402–405 (1997).

Manson, J. C. et al. A single amino acid alteration (101L) introduced into murine PrP dramatically alters incubation time of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. EMBO J. 18, 6855–6864 (1999).

Caughey, B., Kocisko, D. A., Raymond, G. J. & Lansbury, P. T. Aggregates of scrapie associated prion protein induce the cell-free conversion of protease-sensitive prion protein to the protease-resistant state. Chem. Biol. 2, 807–817 (1995).

Kocisko, D. A., Lansbury, P. T. Jr. & Caughey, B. Partial unfolding and refolding of scrapie-associated prion protein: evidence for a critical 16-kDa C-terminal domain. Biochemistry 35, 13434–13442 (1996).

Safar, J. et al. Eight prion strains have PrP(Sc) molecules with different conformations. Nature Med. 4, 1157–1165 (1998).

Caughey, B., Raymond, G. J., Kocisko, D. A. & Lansbury, P. T., Jr. Scrapie infectivity correlates with converting activity, protease resistance, and aggregation of scrapie-associated prion protein in guanidine denaturation studies. J. Virol. 71, 4107–4110 (1997).

Chiesa, R. et al. Accumulation of protease-resistant prion protein (PrP) and apoptosis of cerebellar granule cells in transgenic mice expressing a PrP insertional mutation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5574–5579 (2000).

Tremblay, P. et al. Mutant PrPSc conformers induced by a synthetic peptide and several prion strains. J. Virol. 78, 2088–2099 (2004).

Legname, G. et al. Synthetic mammalian prions. Science 305, 673–676 (2004).

Bueler, H. et al. Mice devoid of PrP are resistant to scrapie. Cell 73, 1339–1347 (1993).

Caughey, B., Ernst, D. & Race, R. E. Congo red inhibition of scrapie agent replication. J. Virol. 67, 6270–6272 (1993).

Bons, N. et al. Natural and experimental oral infection of nonhuman primates by bovine spongiform encephalopathy agents. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 4046–4051 (1999).

Sigurdson, C. J., Spraker, T. R., Miller, M. W., Oesch, B. & Hoover, E. A. PrP(CWD) in the myenteric plexus, vagosympathetic trunk and endocrine glands of deer with chronic wasting disease. J. Gen. Virol. 82, 2327–2334 (2001).

Beekes, M. & McBride, P. A. Early accumulation of pathological PrP in the enteric nervous system and gut-associated lymphoid tissue of hamsters orally infected with scrapie. Neurosci. Lett. 278, 181–184 (2000).

Mabbott, N. A. & Bruce, M. E. The immunobiology of TSE diseases. J. Gen. Virol. 82, 2307–2318 (2001).

Kimberlin, R. H. & Walker, C. A. The role of the spleen in the neuroinvasion of scrapie in mice. Virus Res. 12, 201–212 (1989).

Bruce, M. E., McConnell, I., Will, R. G. & Ironside, J. W. Detection of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease infectivity in extraneural tissues. Lancet 358, 208–209 (2001).

Bruce, M. E., Brown, K. L., Mabbott, N. A., Farquhar, C. F. & Jeffrey, M. Follicular dendritic cells in TSE pathogenesis. Immunol. Today 21, 442–446 (2000).

Montrasio, F. et al. Impaired prion replication in spleens of mice lacking functional follicular dendritic cells. Science 288, 1257–1259 (2000).

Klein, M. A. et al. A crucial role for B cells in neuroinvasive scrapie. Nature 390, 687–690 (1997).

Mabbott, N. A. et al. Tumor necrosis factor α-deficient, but not interleukin-6-deficient, mice resist peripheral infection with scrapie. J. Virol. 74, 3338–3344 (2000).

Brown, K. L. et al. Scrapie replication in lymphoid tissues depends on prion protein-expressing follicular dendritic cells. Nature Med. 5, 1308–1312 (1999).

Matsumoto, M. et al. Role of lymphotoxin and the type I TNF receptor in the formation of germinal centers. Science 271, 1289–1291 (1996).

Mabbott, N. A., Bruce, M. E., Botto, M., Walport, M. J. & Pepys, M. B. Temporary depletion of complement component C3 or genetic deficiency of C1q significantly delays onset of scrapie. Nature Med. 7, 485–487 (2001).

McBride, P. A., Eikelenboom, P., Kraal, G., Fraser, H. & Bruce, M. E. PrP protein is associated with follicular dendritic cells of spleens and lymph nodes in uninfected and scrapie-infected mice. J. Pathol. 168, 413–418 (1992).

Heikenwalder, M., Prinz, M., Heppner, F. L. & Aguzzi, A. Current concepts and controversies in prion immunopathology. J. Mol. Neurosci. 23, 3–12 (2004).

Brown, D. R., Schmidt, B. & Kretzschmar, H. A. Role of microglia and host prion protein in neurotoxicity of a prion protein fragment. Nature 380, 345–347 (1996).

Klein, M. A. et al. Complement facilitates early prion pathogenesis. Nature Med. 7, 488–492 (2001).

Gadjusek, D. C. in Field's Virology 3rd edn (eds Fields, B. N., Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 2851–2900 (Lippincott–Raven, Philadelphia, 1996).

Enari, M., Flechsig, E. & Weissmann, C. Scrapie prion protein accumulation by scrapie-infected neuroblastoma cells abrogated by exposure to a prion protein antibody. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9295–9299 (2001). The first of a series of papers prompting hope for immunotherapy of prion infection, which follows the demonstration of antibody inhibition of cell-free PrP conversion in reference 75.

Peretz, D. et al. Antibodies inhibit prion propagation and clear cell cultures of prion infectivity. Nature 412, 739–743 (2001)

Perrier, V., et al. Anti-PrP antibodies block PrPSc replication in prion-infected cell cultures by accelerating PrPC degradation. J. Neurochem. 89, 454–463 (2004).

Heppner, F. L. et al. Prevention of scrapie pathogenesis by transgenic expression of anti-prion protein antibodies. Science 294, 178–182 (2001).

White, A. R. et al. Monoclonal antibodies inhibit prion replication and delay the development of prion disease. Nature 422, 80–83 (2003).

Solforosi, L. et al. Cross-linking cellular prion protein triggers neuronal apoptosis in vivo. Science 303, 1514–1516 (2004).

Mouillet-Richard, S. et al. Signal transduction through prion protein. Science 289, 1925–1928 (2000).

Cashman, N. R. et al. Cellular isoform of the scrapie agent protein participates in lymphocyte activation. Cell 61, 185–192 (1990).

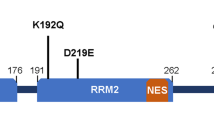

Horiuchi, M., Chabry, J. & Caughey, B. Specific binding of normal prion protein to the scrapie form via a localized domain initiates its conversion to the protease-resistant state. EMBO J. 18, 3193–3203 (1999).

Caughey, B. & Raymond, G. J. The scrapie-associated form of PrP is made from a cell surface precursor that is both protease- and phospholipase-sensitive. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 18217–18223 (1991).

Caughey, B., Raymond, G. J., Ernst, D. & Race, R. E. N-terminal truncation of the scrapie-associated form of PrP by lysosomal protease(s): implications regarding the site of conversion of PrP to the protease-resistant state. J. Virol. 65, 6597–6603 (1991).

Borchelt, D. R., Taraboulos, A. & Prusiner, S. B. Evidence for synthesis of scrapie prion protein in the endocytic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 16188–16199 (1992).

Taraboulos, A., Raeber, A. J., Borchelt, D. R., Serban, D. & Prusiner, S. B. Synthesis and trafficking of prion proteins in cultured cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 3, 851–863 (1992).

Paramithiotis, E. et al. A prion protein epitope selective for the pathologically misfolded conformation. Nature Med. 9, 893–899 (2003). The first hypothesis-driven prion epitope.

Lehto, M. T., Ashman, D. A. & Cashman, N. R. Treatment of ScN2a cells with prion-specific YYR antibodies. Proc. First Intl Conf. Network Excellence: Neuroprion (Paris, 2004).

Schenk, D. et al. Immunization with amyloid-β attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature 400, 173–177 (1999).

Orgogozo, J. M. et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Aβ42 immunization. Neurology 61, 46–54 (2003).

Mallucci, G. et al. Depleting neuronal PrP in prion infection prevents disease and reverses spongiosis. Science 302, 871–874 (2003). In conjunction with reference 158, this paper provides evidence that reduction of PrPC expression might be a reasonable therapeutic approach.

Shyng, S. L., Lehmann, S., Moulder, K. L. & Harris, D. A. Sulfated glycans stimulate endocytosis of the cellular isoform of the prion protein, PrPC, in cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 30221–30229 (1995).

Taraboulos, A. et al. Cholesterol depletion and modification of COOH-terminal targeting sequence of the prion protein inhibit formation of the scrapie isoform. J. Cell. Biol. 129, 121–132 (1995).

Race, R. E., Fadness, L. H. & Chesebro, B. Characterization of scrapie infection in mouse neuroblastoma cells. J. Gen. Virol. 68, 1391–1399 (1987).

Butler, D. A. et al. Scrapie-infected murine neuroblastoma cells produce protease-resistant prion proteins. J. Virol. 62, 1558–1564 (1988).

Clarke, M. C. & Haig, D. A. Evidence for the multiplication of scrapie agent in cell culture. Nature 225, 100–101 (1970).

Schatzl, H. M. et al. A hypothalamic neuronal cell line persistently infected with scrapie prions exhibits apoptosis. J. Virol. 71, 8821–8831 (1997).

Vorberg, I., Raines, A., Story, B. & Priola, S. A. Susceptibility of common fibroblast cell lines to transmissible spongiform encephalopathy agents. J. Infect. Dis. 189, 431–439 (2004).

Sabuncu, E. et al. PrP polymorphisms tightly control sheep prion replication in cultured cells. J. Virol. 77, 2696–2700 (2003).

Rudyk, H. et al. Screening Congo Red and its analogues for their ability to prevent the formation of PrP-res in scrapie-infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 1155–1164 (2000).

Kocisko, D. A. et al. New inhibitors of scrapie-associated prion protein formation in a library of 2000 drugs and natural products. J. Virol. 77, 10288–10294 (2003). A broad-based high-throughput screening of a wide variety of compounds for inhibition of PrPSc formation that builds on the work of reference 93.

Supattapone, S. et al. Branched polyamines cure prion-infected neuroblastoma cells. J. Virol. 75, 3453–3461 (2001).

Birkett, C. R. et al. Scrapie strains maintain biological phenotypes on propagation in a cell line in culture. EMBO J. 20, 3351–3358 (2001).

Maxson, L., Wong, C., Herrmann, L. M., Caughey, B. & Baron, G. S. A solid-phase assay for identification of modulators of prion protein interactions. Anal. Biochem. 323, 54–64 (2003).

Horiuchi, M., Baron, G. S., Xiong, L. W. & Caughey, B. Inhibition of interactions and interconversions of prion protein isoforms by peptide fragments from the C-terminal folded domain. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 15489–15497 (2001).

Rhie, A. et al. Characterization of 2′-fluoro-RNA aptamers that bind preferentially to disease-associated conformations of prion protein and inhibit conversion. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 39697–39705 (2003).

Caughey, W. S., Raymond, L. D., Horiuchi, M. & Caughey, B. Inhibition of protease-resistant prion protein formation by porphyrins and phthalocyanines. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12117–12122 (1998).

Tagliavini, F., Forloni, G., D'ursi, P., Bugiani, M. & Salmona, M. Studies on peptide fragments of prion protein. Adv. Protein Chem. 57, 171–202 (2001).

Zou, W. Q. & Cashman, N. R. Acidic pH and detergents enhance in vitro conversion of human brain PrPC to a PrPSc-like form. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43942–43947 (2002).

Supattapone, S. Prion protein conversion in vitro. J. Mol. Med. (2004).

Soto, C. et al. Reversion of prion protein conformational changes by synthetic β-sheet breaker peptides. Lancet 355, 192–197 (2000). The first demonstration of a peptide that can assist in the unfolding of PrPSc.

Tagliavini, F. et al. Effectiveness of anthracycline against experimental prion disease in syrian hamsters. Science 276, 1119–1122 (1998).

Forloni, G. et al. Tetracyclines affect prion infectivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 10849–10854 (2002).

Shaked, G. M., Engelstein, R., Avraham, I., Kahana, E. & Gabizon, R. Dimethyl sulfoxide delays PrPSC accumulation and disease symptoms in prion-infected hamsters. Brain Res. 983, 137–143 (2003).

Ehlers, B. & Diringer, H. Dextran sulphate 500 delays and prevents mouse scrapie by impairment of agent replication in spleen. J. Gen. Virol. 65, 1325–1330 (1984).

Kimberlin, R. H. & Walker, C. A. Suppression of scrapie infection in mice by heteropolyanion 23, dextran sulfate, and some other polyanions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30, 409–413 (1986).

Farquhar, C. F. & Dickinson, A. G. Prolongation of scrapie incubation period by an injection of dextran sulphate 500 within the month before or after infection. J. Gen. Virol. 67, 463–473 (1986).

Priola, S. A., Raines, A. & Caughey, W. S. Porphyrin and phthalocyanine anti-scrapie compounds. Science 287, 1503–1506 (2000). Building on reference 100, this is the first demonstration that cyclic tetrapyrroles can substantially extend the incubation periods of rodents inoculated with scrapie.

Murakami-Kubo, I. et al. Quinoline derivatives are therapeutic candidates for transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. J. Virol. 78, 1281–1288 (2004).

Barret, A. et al. Evaluation of quinacrine treatment for prion diseases. J. Virol. 77, 8462–8469 (2003).

Race, R., Oldstone, M. & Chesebro, B. Entry versus blockade of brain infection following oral or intraperitoneal scrapie administration: role of prion protein expression in peripheral nerves and spleen. J. Virol. 74, 828–833 (2000).

Fischer, M. et al. Prion protein (PrP) with amino-proximal deletions restoring susceptibility of PrP knockout mice to scrapie. EMBO J. 15, 1255–1264 (1996).

Beringue, V., Adjou, K. T., Lamoury, F., Maignien, T., Deslys, J. P., Race, R. & Dormont, D. Opposite effects of dextran sulfate 500, the polyene antibiotic MS-8209, and Congo red on accumulation of the protease-resistant isoform of PrP in the spleens of mice inoculated intraperitoneally with the scrapie agent. J. Virol. 74, 5432–5440 (2000).

Korth, C., May, B. C., Cohen, F. E. & Prusiner, S. B. Acridine and phenothiazine derivatives as pharmacotherapeutics for prion disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9836–9841 (2001).

Bate, C., Salmona, M., Diomede, L. & Williams, A. Squalestatin cures prion-infected neurones and protects against prion neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. (in the press).

Diringer, H. & Ehlers, B. Chemoprophylaxis of scrapie in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 72, 457–460 (1991).

Caughey, B. & Raymond, G. J. Sulfated polyanion inhibition of scrapie-associated PrP accumulation in cultured cells. J. Virol. 67, 643–650 (1993).

Gabizon, R., Meiner, Z., Halimi, M. & Bensasson, S. A. Heparin-like molecules bind differentially to prion proteins and change their intracellular metabolic-fate. J. Cell. Physiol. 157, 319–325 (1993).

Wong, C. et al. Sulfated glycans and elevated temperature stimulate PrPSc dependent cell-free formation of protease-resistant prion protein. EMBO J. 20, 377–386 (2001).

Ben-Zaken, O. et al. Cellular heparan sulfate participates in the metabolism of prions. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 40041–40049 (2003).

Deleault, N. R., Lucassen, R. W. & Supattapone, S. RNA molecules stimulate prion protein conversion. Nature 425, 717–720 (2003).

Caughey, B. & Kocisko, D. A. Prion diseases: a nucleic-acid accomplice? Nature 425, 673–674 (2003).

Caughey, B. & Race, R. E. Potent inhibition of scrapie-associated PrP accumulation by Congo red. J. Neurochem. 59, 768–771 (1992). The first identification of a PrPSc inhibitor in live cells, a demonstration that even preternaturally hardy prion infectivity could be vulnerable to chemotherapy.

Ingrosso, L., Ladogana, A. & Pocchiari, M. Congo red prolongs the incubation period in scrapie-infected hamsters. J. Virol. 69, 506–508 (1995).

Caughey, B., Brown, K., Raymond, G. J., Katzenstien, G. E. & Thresher, W. Binding of the protease-sensitive form of PrP (prion protein) to sulfated glycosaminoglycan and Congo red. J. Virol. 68, 2135–2141 (1994).

Caspi, S. et al. The anti-prion activity of Congo red. Putative mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3484–3489 (1998).

Demaimay, R. et al. Structural aspects of Congo red as an inhibitor of protease-resistant prion protein formation. J. Neurochem. 71, 2534–2541 (1998).

Demaimay, R., Chesebro, B. & Caughey, B. Inhibition of formation of protease-resistant prion protein by trypan blue, sirius red and other Congo red analogs. Arch. Virol. [Suppl] 16, 277–283 (2000).

Poli, G. et al. In vitro evaluation of the anti-prionic activity of newly synthesized congo red derivatives. Arzneimittelforschung. 53, 875–888 (2003).

Gilch, S. et al. Intracellular re-routing of prion protein prevents propagation of PrP(Sc) and delays onset of prion disease. EMBO J. 20, 3957–3966 (2001).

Caughey, B., et al. Inhibition of protease-resistant prion protein accumulation in vitro by curcumin. J. Virol. 77, 5499–5502 (2003).

Priola, S. A., Raines, A. & Caughey, W. Prophylactic and therapeutic effects of phthalocyanine tetrasulfonate in scrapie-infected mice. J. Infect. Dis. 188, 699–705 (2003).

Pocchiari, M., Schmittinger, S. & Masullo, C. Amphotericin B delays the incubation period of scrapie in intracerebrally inoculated hamsters. J. Gen. Virol. 68, 219–223 (1987).

Dormont, D. Approaches to prophylaxis and therapy. Br. Med. Bull. 66, 281–292 (2003).

Mange, A. et al. Amphotericin B inhibits the generation of the scrapie isoform of the prion protein in infected cultures. J. Virol. 74, 3135–3140 (2000).

Marella, M., Lehmann, S., Grassi, J. & Chabry, J. Filipin prevents pathological prion protein accumulation by reducing endocytosis and inducing cellular PrP release. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25457–25464 (2002).

Adjou, K. T. et al. MS-8209, an amphotericin B analogue, delays the appearance of spongiosis, astrogliosis and PrPres accumulation in the brain of scrapie-infected hamsters. J. Comp. Pathol. 122, 3–8 (2000).

Doh-ura, K., Iwaki, T. & Caughey, B. Lysosomotropic agents and cysteine protease inhibitors inhibit accumulation of scrapie-associated prion protein. J. Virol. 74, 4894–4897 (2000). The first demonstration of the inhibitory efficacy of quinacrine, the antimalarial drug that is currently being tested in humans.

Sigurdsson, E. M. et al. Copper chelation delays the onset of prion disease. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 46199–46202 (2003).

Scott, M. R., Kohler, R., Foster, D. & Prusiner, S. B. Chimeric prion protein expression in cultured cells and transgenic mice. Protein Sci. 1, 986–997 (1992).

Priola, S. A., Caughey, B., Race, R. E. & Chesebro, B. Heterologous PrP molecules interfere with accumulation of protease-resistant PrP in scrapie-infected murine neuroblastoma cells. J. Virol. 68, 4873–4878 (1994).

Horiuchi, M., Priola, S. A., Chabry, J. & Caughey, B. Interactions between heterologous forms of prion protein: Binding, inhibition of conversion, and species barriers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5836–5841 (2000).

Goldmann, W., Hunter, N., Smith, G., Foster, J. & Hope, J. PrP genotype and agent effects in scrapie: change in allelic interaction with different isolates of agent in sheep, a natural host of scrapie. J. Gen. Virol. 75, 989–995 (1994).

Palmer, M. S., Dryden, A. J., Hughes, J. T. & Collinge, J. Homozygous prion protein genotype predisposes to sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Nature 352, 340–342 (1991).

Prusiner, S. B. et al. Transgenetic studies implicate interactions between homologous PrP isoforms in scrapie prion replication. Cell 63, 673–686 (1990). This paper, together with several others (references 98 and 143–150), establish a rationale for therapeutic approaches based on expression of interfering PrP molecules, or PrP fragments, in the host.

Chabry, J., Caughey, B. & Chesebro, B. Specific inhibition of in vitro formation of protease-resistant prion protein by synthetic peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13203–13207 (1998).

Chabry, J. et al. Species-independent inhibition of abnormal prion protein (PrP) formation by a peptide containing a conserved PrP sequence. J. Virol. 73, 6245–6250 (1999).

Brown, P. Drug therapy in human and experimental transmissible spongiform encephalopathy. Neurology 58, 1720–1725 (2002).

Doh-ura, K. et al. Treatment of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy by intraventricular drug infusion in animal models. J. Virol. 78, 4999–5006 (2004). A demonstration that the direct administration of PrPSc inhibitors to the brain ventricles can enhance the beneficial effects of drugs late in the incubation period, an approach that is currently being tested in human CJD patients.

Kobayashi, Y., Hirata, K., Tanaka, H. & Yamada, T. [Quinacrine administration to a patient with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease who received a cadaveric dura mater graft — an EEG evaluation]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 43, 403–408 (2003).

Nakajima, M. et al. Results of quinacrine administration to patients with Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn Disord. 17, 158–163 (2004).

Otto, M. et al. Efficacy of flupirtine on cognitive function in patients with CJD: a double-blind study. Neurology 62, 714–718 (2004). A demonstration of beneficial effects of a drug on CJD patients.

Taylor, D. M. Inactivation of transmissible degenerative encephalopathy agents: a review. Vet. J. 159, 10–17 (2000).

Kocisko, D. A., Morrey, J. D., Race, R., Chen, J. & Caughey, B. Evaluation of new cell-culture inhibitors of PrP–res against scrapie infection in mice. J. Gen. Virol. 85, 2479–2484 (2004).

Daude, N., Marella, M. & Chabry, J. Specific inhibition of pathological prion protein accumulation by small interfering RNAs. J. Cell Sci. 116, 2775–2779 (2003). This paper, along with reference 84, provides evidence that active reduction of PrPC expression might be a reasonable therapeutic approach.

Prusiner, S. B. Shattuck lecture — neurodegenerative diseases and prions. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1516–1526 (2001).

Caughey, B. & Lansbury, P. T. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26, 267–298 (2003).

Kimberlin, R. H. & Walker, C. A. The antiviral compound HPA-23 can prevent scrapie when administered at the time of infection. Arch. Virol. 78, 9–18 (1983). This and an earlier paper by this group are the first to demonstrate prophylactic anti-scrapie activity of polyanionic molecules.

Lasmezas, C. I. et al. Transmission of the BSE agent to mice in the absence of detectable abnormal prion protein. Science 17, 402–405 (1997).

Acknowledgements

N.R.C.'s work is supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Institute of Infection and Immunity), Caprion Pharmaceuticals and McDonald's Corp.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

N.R.C is receives funding for research from Caprion Pharmaceuticals. B.C holds patents on the use of Congo red, cyclic tetrapyrroles and PrP peptides for TSE treatments.

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

Entrez Gene

OMIM

FURTHER INFORMATION

Encyclopedia of Life Sciences

Glossary

- TRANSMISSIBLE SPONGIFORM ENCEPHALOPATHY

-

A class of infectious diseases characterized by neuronal degeneration, spongiform change, gliosis and accumulation of amyloid protein deposits.

- SPONGIFORM CHANGE

-

Microvacuolization of brain tissue, which typically accompanies prion disease.

- CREUTZFELDT–JAKOB DISEASE

-

(CJD). The most common human prion disease, classically comprising sporadic, familial and iatrogenic forms, and now including variant CJD (vCJD).

- VARIANT CJD

-

(vCJD). A newly emergent form of human prion disease, initially linked to comsumption of cattle afflicted with bovine spongiform encephalopathy.

- BOVINE SPONGIFORM ENCEPHALOPATHY

-

(BSE). A naturally acquired transmissible spongiform encephalopathies of cattle, epidemically amplified by feed supplementation with rendered products from afflicted bovines.

- CHRONIC WASTING DISEASE

-

(CWD). A relatively contagious prion disease of captive and wild cervids (elk and deer).

- SCRAPIE

-

A naturally acquired prion disease of sheep, clinically recognized for ∼300 years. Mouse-adapted scrapie agent strains are now used in many paradigms to identify therapies to prion disease.

- PRION HYPOTHESIS

-

The proposal that transmissible spongiform encephalopathies infectivity comprises the conformational conversion of the host-encoded cellular prion protein PrPC into the disease-associated isoform PrPSc.

- PrPC

-

The native, protease-sensitive, normally expressed form of PrP, named for its 'cellular' location.

- PrP-SEN

-

A generic operational term referring to forms of PrP that are protease-sensitive. This includes native PrPC as well as various non-native or abnormal forms of PrP (for example, recombinant or mutant forms) that are protease-sensitive.

- PrPSC

-

The native disease-associated isoform of PrP, originally named for its association with scrapie. Now often used generically to refer to the disease-associated form of PrP in prion diseases other than scrapie.

- PrP-RES

-

A generic term referring to the disease-associated form of PrP that is recognizable by its partial resistance to proteolytic digestion, and therefore partially synonymous with PrPSc when the latter is applied generically. Also commonly used to denote the highly protease-resistant 27–30 kDa product of partial proteolysis of native disease-associated PrP.

- PRNP

-

The human gene that encodes PrP. Also used to designate the prion protein gene in other species, although the mouse nomenclature is Prnp.

- GERSTMANN–STRAUSSLER SYNDROME

-

A familial prion disease, linked with mutations in the PRNP open reading frame.

- GLIOSIS

-

Activation and proliferation of astrocytes and microglial cells in the brain.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cashman, N., Caughey, B. Prion diseases — close to effective therapy?. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3, 874–884 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1525

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1525

This article is cited by

-

Human cerebral organoids as a therapeutic drug screening model for Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Prions Strongly Reduce NMDA Receptor S-Nitrosylation Levels at Pre-symptomatic and Terminal Stages of Prion Diseases

Molecular Neurobiology (2019)

-

Pharmacological chaperone reshapes the energy landscape for folding and aggregation of the prion protein

Nature Communications (2016)

-

Discovery of Novel Anti-prion Compounds Using In Silico and In Vitro Approaches

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

The distribution of four trace elements (Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn) in forage and the relation to scrapie in Iceland

Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica (2010)