Abstract

The concept and terminology of borderline epithelial tumors of the ovary have been controversial for over a century, in spite of the acceptance of a borderline category in almost all current classifications of ovarian tumors. Typically, borderline tumors are noninvasive neoplasms that have nuclear abnormalities and mitotic activity intermediate between benign and malignant tumors of similar cell type. Borderline tumors of all surface epithelial cell types have been studied. The most common and best understood are serous borderline tumors and mucinous borderline tumors of intestinal type, which are the subject of this review. Some of the most challenging issues for serous tumors include: the criteria and clinical behavior of stromal microinvasion; the high prevalence of synchronous extraovarian disease; the classification and histopathologic features of associated peritoneal tumor implants, especially invasive implants; and, the prognostic significance of micropapillary tumors. The mucinous borderline tumors of intestinal type have a different set of considerations, including: their frequently heterogeneous composition with coexisting benign, borderline and malignant elements; the classification and significance of accompanying noninvasive carcinoma; the recognition of stromal invasion, including microinvasion and expansile invasion; and, the historically misunderstood relationship to pseudomyxoma peritonei. All of these issues are discussed in this presentation, as are the important gross and microscopic features of serous and mucinous borderline tumors and pertinent information on their treatment and prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The concept of borderline epithelial tumors of the ovary has faced controversy for over a century. In 1898, Hermann Johannes Pfannenstiel illustrated and described papillary ovarian cystadenomas with ‘clinical features that stand on the border of malignancy’.1 Similarly, Carl Abel in 1901 described proliferating papillary cystadenomas ‘on the border line (sic) between benign and malignant growths’.2 Howard Taylor introduced the term ‘semi-malignant’ tumor in 19293 and with his colleague Munnell delineated a ‘borderline’ category for a subset of serous cystadenocarcinomas in their historically important report on the clinical behavior of ovarian cancers.4 The features of mucinous borderline tumors were probably first documented in a study from the Cleveland Clinic in 1955.5 Numerous other adjectives appeared in the literature in the ensuing years to describe proliferative ovarian epithelial tumors that appeared to be ‘intermediate’ in their clinicopathologic features between clearly benign cystadenomas and unquestionably malignant cystadenocarcinomas. In 1961, the Cancer Committee of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) proposed a classification of common primary epithelial ovarian tumors which was adopted in 1970 and became effective on January 1, 1971.6 In the FIGO classification, the common primary epithelial tumors were subdivided into three groups: benign cystadenoma; cystadenoma with proliferating activity of the epithelial cells and nuclear abnormalities, but with no infiltrative destructive growth (low potential malignancy); and, cystadenocarcinoma.7

Within the next decade, a few large series of ovarian borderline or proliferative epithelial tumors were published.8, 9, 10, 11 The World Health Organization (WHO) applied the designation ‘tumor of borderline malignancy’ and added the synonym ‘carcinoma of low malignant potential’ (LMP) in their 1973 classification of ovarian tumors.12 According to the WHO definition, a borderline epithelial tumor lacks obvious invasion of the stroma and has mitotic activity and nuclear abnormalities intermediate between clearly benign and unquestionably malignant tumors of a similar cell. Within the following 10 years, the term ‘tumor of LMP’ became popular, and it replaced ‘carcinoma of LMP’ as a synonym for cystadenoma of borderline malignancy in the 1999 combined classification of the International Society of Gynecologic Pathologists and the WHO.13

In spite of the imprimatur of several international organizations, the concept of borderline ovarian epithelial tumors was not universally accepted. The vanguard of proponents was led by pathologists and gynecologists in Scandinavia,8, 10, 11, 14 and a few in the United States9, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and Australia.20, 21 Some pathologists in leading academic medical centers refused to incorporate borderline tumor into their diagnostic nomenclature, routinely diagnosing most serous and mucinous borderline tumors as well-differentiated cystadenocarcinoma until quite late in the 20th century. For instance, a recent review of early-stage ovarian carcinomas from 1980 through 2000 at a leading cancer center resulted in reclassification of 29% of the cases as borderline tumors.22 As a result, patients with Stage I borderline tumors often received adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy, sometimes resulting in death due to therapy rather than the tumor.

In the past 10 years, ‘atypical proliferating (or atypical proliferative) tumor’ has been championed as an alternative designation for borderline tumor.23 Arguments for and against this term have been presented in the literature and the polemics will not be detailed here. Suffice it to say, the concept and terminology for borderline tumors continues to be challenged. Because ‘borderline tumor’ is the term used in the recently published 2003 WHO classification24 and seems to be the most popular among gynecologic pathologists and gynecologic oncologists, it will be used throughout this discussion.

The absence of obvious stromal invasion is a principal diagnostic criterion for borderline tumors. Identification of stromal invasion is relatively straightforward for the intracystic papillary proliferations, typical of borderline serous tumors, but is a particularly vexing problem in predominantly glandular tumors, such as those of endometrioid and mucinous types. In the latter, complex aggregates of glands and cysts often have little intervening ovarian stroma. In addition, one or more foci of stromal microinvasion by cells with the same borderline cytologic features may be found in otherwise typical serous and mucinous borderline tumors. Size limits of 3 mm in maximum dimension with an area not to exceed 10 mm2 are commonly used,25, 26, 27 although some investigators include foci up to 5 mm.28 However, the maximum size has not been scientifically validated, nor has the number of allowable foci. As discussed below, we and others believe borderline tumors with stromal microinvasion should be distinguished from small foci of invasive serous or mucinous carcinoma arising in a borderline tumor.26, 29

While the original WHO classification required that borderline tumors display only an intermediate degree of cellular proliferation and nuclear abnormalities less than those of unquestionable carcinoma, a wide spectrum of atypicality may be found. Architectural and cytologic patterns of noninvasive carcinoma may be found within otherwise typical borderline tumors, especially in the mucinous category. These include pronounced degrees of cellular stratification, often with the formation of intraglandular bridges, cribriform patterns and micropapillae devoid of connective tissue cores in which the neoplastic cells have high-grade (moderate-to-severe) nuclear atypia.9, 15 Such changes have also been referred to as ‘intraglandular carcinoma’29 and ‘intraepithelial carcinoma’.13 Of course, areas of unequivocally infiltrative carcinoma may also be found within a borderline tumor.

Borderline tumors of every surface epithelial cell type (serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, transitional cell and mixed epithelial cell) have now been reported. However, the serous and mucinous borderline tumors are the most common by far, and those about which we have the most meaningful clinical and pathological data. Thus, only these types will be considered here.

Borderline serous tumors

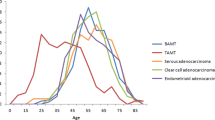

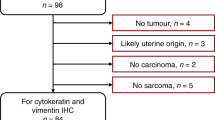

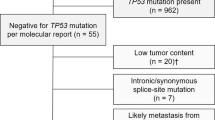

Borderline tumors of serous type have been extensively investigated over many generations by expert pathologists and gynecologists throughout the world. About 9–15% of all serous neoplasms are of borderline type.16, 20 Patients tend to be relatively youthful with a mean age of 38 years (range, 17–77).30 According to the FIGO staging system,27 68% are Stage I, 11% Stage II, 21% Stage III and less than 1% Stage IV. Bilateral ovarian tumors are found in 40% of cases.31 Grossly, most are cystic and papillary and may not be distinguishable from papillary serous cystadenocarcinomas or markedly papillary cystadenomas (Figure 1). In our series of 98 patients, tumor size ranged from 2 to 25 cm, with a mean of 10 cm.31 Papillary excrescences on the external cortical surface occur in 48% of all patients and in 27% of those with Stage I tumors (Figure 2).31 Documentation of a surface component or rupture is important for accurate staging. Stage I tumors with either of these findings are placed in Stage Ic.27 Ovarian surface growth in borderline tumors does not result from invasion though the cortex but represents direct origin from surface epithelium. In almost 10% of cases, the entire lesion is an exophytic papillary surface borderline tumor unassociated with internal cysts or with only a minor cystic component.31 These must be distinguished from true papillary mesotheliomas of the peritoneum and ovary.32 The least frequent variant of serous borderline tumor is a predominantly solid adenofibromatous or cystadenofibromatous borderline tumor.33

Histologically, typical borderline serous tumors are noninvasive proliferative neoplasms characterized by multiple fibrous papillae with extensive and complex hierarchical branching (Figure 3). The epithelial cells covering the papillae are crowded and form multilayered cellular tufts (Figure 4). Detachment and exfoliation of cells from the papillae are characteristic. Some of the exfoliated cells are eosinophilic and have a rounded shape. Many of the epithelial cells covering the papillae are ciliated. Cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm may be especially prominent in pregnant patients. The epithelial cells generally show only mild-to-moderate nuclear atypia. A few tumors have focal severe atypia, often in cells of eosinophilic type, which only rarely qualify for the designation of intraepithelial carcinoma.16, 34 Mitotic figures may be absent or found in very small numbers. Only about 5% of tumors have more than four mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields.16, 34 Abnormal mitotic figures are not usually observed.34 Most tumors have been diploid, including all 18 cases in which flow cytometry analysis was performed on fresh tumor samples.35 Psammoma bodies are most often found in foci of stromal microinvasion and in clusters of exfoliated cells in the cyst fluid, within the lumen of the adjacent fallopian tube and in peritoneal tumor implants.

Micropapillary Variant

A small minority of tumors have an unusually prominent micropapillary histologic pattern (Figures 5, 6 and 7), usually in conjunction with an otherwise typical borderline tumor, but occasionally alone.36, 37 Less than 6% of nonconsultation hospital cases of serous borderline tumors in one large series38 and 12–18% in other series39 were of the micropapillary type. It is generally agreed that micropapillary tumors, when compared to typical borderline tumors, are more often bilateral, have a higher frequency of exophytic surface tumor and a greater proportion are of advanced stage. Histologically, the micropapillary variant is characterized by an exuberant cellular proliferation that emanates from the surfaces of fibrous papillae, without a hierarchical branching pattern (Figure 5) or directly from cyst walls. The proliferating cells form long, delicate projections with a complex filigree pattern (Figure 6) or thick cribriform formations (Figure 7).36, 37 It has been proposed that the papillae should be at least 5 times as long as wide.40 A continuous 5 mm micropapillary or cribriform growth pattern in a single slide is generally required for the diagnosis of micropapillary serous borderline tumor.36, 37 High-grade nuclear atypia is absent. This latter feature is important, since widespread high-grade atypia indicates the tumor is a conventional papillary serous carcinoma and not a micropapillary or typical borderline tumor (Figure 8). Some high-grade ovarian carcinomas, especially surface serous carcinomas, are not accompanied by obvious invasion of the stroma.41

Stromal Microinvasion

Isolated foci of microinvasion are found in about 10% of serous borderline tumors.30, 42, 43 Utilizing immunostaining for epithelial markers, microinvasion has been detected in 13% of cases.44 Tumors in pregnant patients apparently have an especially high frequency of stromal microinvasion, occurring in 80% of 10 pregnant patients in one series.45 Microinvasive foci usually consist of individual cells or small clusters of cells, often with eosinophilic cytoplasm, within the stroma of the papillary projections or cyst wall (Figure 9). Small confluent nests or aggregates of papillae in the stroma are less often seen. Clear zones or clefts often surround the microinvasive foci. Lymphatic invasion may also be found. The term ‘serous borderline tumor with stromal microinvasion,’ rather than invasive serous carcinoma, is appropriately applied when the size of the invasive lesions conform to the dimensions listed earlier in this discussion. It is important to recognize that even predominantly cystic tumors have a minor stromal component. Orderly penetration of this indigenous stroma by epithelial evaginations, tubular structures or microcysts with papillae are common.27 Usually, the surrounding stroma appears undisturbed, but sometimes it is edematous or has a slightly ‘reactive’ appearance that may be misconstrued as an early desmoplastic reaction to invasive tumor.

Occasional microinvasive tumors have recurred,38, 46 and a nonsignificant higher frequency of advanced-stage microinvasive tumors was reported in one recent study.38 The clinical behavior of tumors with or without stromal microinvasion, whether typical or micropapillary, probably does not significantly differ when stage and peritoneal implant type (invasive or non-invasive) are comparable.30, 38, 40, 42, 43 A few patients with stage I microinvasive tumors have developed progressive disease and microinvasion may be a risk factor for patients with high-stage disease.47 In some borderline serous tumors, especially those with a micropapillary pattern, areas of low-grade or high-grade invasive serous carcinoma are present. With this in mind, rigorous sampling is necessary for all serous borderline tumors, particularly those with any unusual feature.

Peritoneal Implants

Serous borderline tumors have a disconcertingly high frequency of extraovarian disease. Peritoneal implants on serosal and omental surfaces are found at the time of initial operation in 20–46% of patients.30 There is a very high correlation between exophytic tumor on the ovarian surface and synchronous implants. Almost two-thirds of patients whose ovarian tumor has an exophytic surface component have implants, and 94% of patients with implants have an exophytic surface component on their ovarian tumor.31 Thus, an ovarian exophytic component is a strong marker for synchronous extraovarian peritoneal disease (Figure 2).

For about 15 years, peritoneal implants have been classified into invasive and noninvasive categories with noninvasive implants subclassified as epithelial, desmoplastic or both.48 Desmoplastic implants may also involve the surface of the ovary and the walls of cysts where they may bridge adjacent papillary processes. Such ‘autoimplants’ must be distinguished from true stromal invasion in ovarian serous carcinomas.49 From 83 to 96% of peritoneal implants are noninvasive. Correlations between prognosis and the microscopic features of peritoneal and omental implants have been demonstrated. In the original study defining the types of peritoneal implants, three microscopic features correlated with an adverse prognosis: invasive growth, severe cytologic atypia and the presence of mitotic activity.48 In addition, residual postoperative tumor as assessed by the surgeon was an adverse finding, and those implants with marked nuclear atypia seemed to be more aggressive. In subsequent studies, mitotic activity has not proven to be a significant predictor of recurrence or death.50 It is important to emphasize that invasive implants are commonly found together with noninvasive implants. Hence, surgeons should be encouraged to biopsy as many implants as possible, and pathologists must liberally sample omentectomy specimens in search of invasive implants.

Noninvasive implants typically are plastered on the peritoneal surface (Figures 10 and 11). The recognition of invasion in desmoplastic implants may be problematic, especially in small biopsies. Underlying tissue is absent in about 25% of biopsies of implants.51 Its absence generally indicates the implant was easily stripped away and thus was noninvasive.40 In the omentum, desmoplastic implants may produce fibrous adhesions between fat lobules, causing difficulty in determining whether actual invasion has occurred (Figure 12). Generally, desmoplastic noninvasive implants consist predominantly of cellular fibrous or granulation-like tissue in which are imbedded small tumor nests, papillae or even single cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 13). The neoplastic elements may be inconspicuous at low magnification. They often, but not always, seem to blend in with the connective tissue and some cells may resemble mesothelial cells. Invasive implants generally also are desmoplastic. In contrast to noninvasive implants, invasive implants engulf and/or replace omental adipose tissue (Figure 14). Sometimes tumor may be seen infiltrating between individual fat cells. The invasive desmoplastic implants usually have a greater proportion of proliferating neoplastic epithelial cells that often produce complex glandular, micropapillary and cribriform patterns (Figure 15). In some cases, the diagnosis of invasive implants inevitably requires an element of subjectivity.

Higher magnification of desmoplastic noninvasive implant of serous borderline tumor seen in Figure 11. Small groups of tumor cells are embedded in inflamed connective tissue.

To complicate matters further, some investigators have used different diagnostic criteria to determine invasion in implants.51, 52 The presence of single cells or small groups of cells resembling those seen in stromal microinvasion in ovarian borderline tumors has been used as a feature of ‘early invasion’,52 but such cells are commonly found in desmoplastic implants, have not correlated with prognosis and are not generally regarded as an indicator of invasion.51 Recently, the importance of diagnosing implants as invasive or noninvasive was challenged and new histologic features for implant classification advocated.51 In one study, the authors concluded that those implants that either had a micropapillary or cribriform pattern or were composed of small solid epithelial nests (5–10 cells) surrounded by a clear space were equivalent to invasive implants, regardless of whether invasion of normal underlying tissue could be demonstrated.51 By this expanded definition, 45% of the implants in that study were classified as invasive. It must be noted that 90% of the cases were seen in consultation and almost half of the ovarian tumors were of the micropapillary type. In addition, the authors proposed that the term ‘invasive implant’ was inaccurate and misleading and should be replaced by ‘well-differentiated serous carcinoma’ or ‘metastatic micropapillary serous carcinoma’ when associated with an ovarian micropapillary tumor. At present, this approach is highly controversial and has not been accepted by most gynecologic pathologists.

When the original, more restrictive criteria are used, invasive implants are very uncommon, occurring in only 4–13% of patients with high-stage disease.30, 38, 48, 50 In a recent study of advanced-stage borderline serous tumors from a population of more than 4 million people in British Columbia, only six patients (12%) with invasive implants were found over a 17-year period.50 In a large series of 99 patients with advanced disease at diagnosis, 6% of 81 typical borderline tumors and 17% of 18 micropapillary/cribriform borderline tumors had invasive implants.39 Invasive implants may have histologic features of either borderline tumor or low-grade serous carcinoma.38, 53, 54 In one study, those with features of low-grade serous carcinoma had a worse prognosis than those with borderline histology.54 It cannot be overemphasized that typical ovarian serous carcinomas, as well as serous borderline tumors, may have peritoneal and omental metastases with noninvasive epithelial and desmoplastic growth patterns.

Source of Peritoneal Implants

It is controversial whether the neoplastic extraovarian lesions associated with borderline serous tumors are implants from the ovarian tumor or arise independently from the peritoneum in a multicentric fashion. There is considerable evidence for the implantation theory. As mentioned earlier, most high-stage tumors have exophytic growth on the ovarian surface, a finding that is a strong marker for synchronous peritoneal implants.31 Fragments of ovarian exophytic tumor often undergo torsion and partial infarction. Not infrequently, they may become detached from the ovary and embedded in the cul-de-sac or on serosal surfaces where surviving epithelium continues to proliferate. It is also common to see clusters of tumor cells in the lumen of the adjacent fallopian tube, so we know that exfoliated tumor cells can be transported from ovarian surface tumor into the peritoneal cavity. However, the peritoneal, omental and serosal lesions often are associated with endosalpingiosis, leading to a theory that some ‘implants’ actually arise in situ from endosalpingiosis. While endosalpingiosis is generally regarded as a benign metaplastic lesion, it has recently been postulated that some examples of endosalpingiosis associated with implants actually are highly differentiated neoplastic implants, rather than precursor benign lesions.38, 55 Borderline tumors also occasionally originate in the peritoneum in the absence of an ovarian tumor.56, 57 These primary peritoneal borderline serous tumors are histologically indistinguishable from noninvasive implants associated with ovarian borderline tumors. Thus, it is likely that extraovarian tumor develops as peritoneal implants from an ovarian tumor in some cases and as multicentric peritoneal lesions in other cases.31 Molecular genetic studies have shown supportive evidence for both mechanisms.58, 59, 60

Lymph Nodal Metastasis

Para-aortic and pelvic lymph node involvement is found in 7–23% of cases with node sampling at the time of surgery, and a few patients develop postoperative distant disease in cervical and scalene lymph nodes.53, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65 Small clusters of tumor cells within the subcapsular sinuses or within the substance of the node probably are true embolic metastases of the tumor (Figure 16). They must be distinguished from mesothelial cells.66 In contrast, tumor closely associated with nodal endosalpingiosis in the fibrous capsule and trabecula may represent multicentric tumors originating in the lymph nodes, rather than true metastases (Figure 17). Synchronous lymph node involvement found during staging procedures generally is of microscopic dimension and prognosis does not seem to be adversely affected. In contrast, delayed nodal metastases tend to more extensively replace the nodes and may represent more aggressive disease, especially when located outside the abdominal cavity.61

Prognosis

Prognosis is excellent for patients with limited extent of tumor and surprisingly good even for those with extensive peritoneal disease. Only a very small number of documented patients with Stage I disease have developed progressive disease, usually in the form of low-grade serous carcinoma within the peritoneal cavity or occasionally in extra-abdominopelvic sites. The survival rate for patients with Stage I tumors ranges from 95 to 100%.38, 53, 54, 67, 68, 69 Long-term follow-up, however, is required for an accurate determination of recurrence rates. For instance, in a report of 160 Stage I tumors, 11 patients (6.8%) developed recurrent tumor, often after prolonged postoperative intervals of 7–39 years (mean, 16 years), and eight were fatal.54

Unresected peritoneal implants of borderline serous tumors often remain dormant, and some have apparently undergone spontaneous regression. Morbidity may result from adhesions and recurrent intestinal obstruction caused by peritoneal implants and/or their treatment. As noted earlier, some patients have died as a result of postoperative radiation or chemotherapy. Recurrent tumor may develop after latent intervals as long as 20–50 years. Some of these may be due to new tumors arising from the peritoneum or from endosalpingiosis.

Almost all deaths due to tumor occur in patients with high-stage disease. In a study of 174 cases treated at the Norwegian Radium Hospital from 1970 to 1982, only six patients (3%) died of disease.67 The 15-year corrected survival was 100% for 148 Stage I tumors and exceeded 95% for all cases, although survival fell to 77% for 13 Stage II tumors and 64% for 13 Stage III tumors.67 In a series of 99 high-stage cases, 17% of patients died of disease, some after very prolonged intervals.39 A recent tabulation of seven series found mortality rates of 6% for 72 patients with Stage II disease and 19% for 159 patients with Stage III disease.50 The mortality rate for Stage III tumors in multiple reported series ranges from 6 to 36%.30, 38, 39, 48, 50, 67 While most fatal cases occur in patients with invasive peritoneal implants, this is not invariable, as progressive disease and death does occasionally follow noninvasive implants.30, 39, 50

The prognostic significance of the micropapillary variant has been hotly contested. One group of investigators believes that it signifies a more aggressive tumor that should be diagnosed as a micropapillary serous carcinoma, even in the absence of stromal invasion.36, 37, 70 The proponents of this viewpoint regard the micropapillary lesion as a specific type of low-grade serous carcinoma that develops in a stepwise fashion from typical borderline tumors and has preinvasive and invasive stages. According to this theory, it is the micropapillary tumor that gives rise to progressive peritoneal metastases, not the typical borderline tumor. They have presented morphologic, molecular genetic, cytogenetic and clinical data in support of their argument.71, 72 In some studies, but not in others, micropapillary tumors have a greater tendency to be associated with invasive peritoneal implants and to have shorter disease-free intervals when they recur than typical serous borderline tumors.37, 38, 39, 40, 73 Yet, some investigators have not found the overall survival rates for micropapillary tumors to be significantly different from those of typical borderline tumors of comparable stage and type of peritoneal implant.38, 39 Moreover, some typical serous borderline tumors without a micropapillary component are associated with progressive disease. The debate will undoubtedly continue. At this time, most gynecologic pathologists continue to classify noninvasive (and microinvasive) micropapillary serous tumors with cytologic borderline features as a morphologic variant of serous borderline tumor, rather than as low-grade micropapillary serous carcinoma.38, 39, 40, 50, 73, 74 Regardless of terminology, it is especially important to perform thorough microscopic sampling in all micropapillary tumors to be certain that areas of invasive serous carcinoma are absent.

Treatment

Because of the highly favorable prognosis for patients with serous borderline tumors, treatment has increasingly become more conservative. Complete surgical staging is of great importance. Stage I tumors are usually treated by surgery alone with long-term follow-up to detect late recurrences. Conservation of fertility is often an issue in view of the relatively young age of many patients. About 15% of patients with Stage Ia tumors treated by unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy develop a second primary borderline tumor in the preserved contralateral ovary.30, 34 Ovarian cystectomy without oophorectomy is done for selected patients with Stage I lesions if the tumor is loosely attached and complete removal can be accomplished.75 The approach to high-stage disease is less uniform. Generally, surgical debulking of tumor with thorough microscopic examination of implants to detect invasion is done. In the absence of invasive implants, watchful expectancy is practiced in many medical centers. Adjuvant chemotherapy is often reserved for those patients with invasive implants, bulky unresectable residual tumor or clinically progressive disease. The routine use of adjuvant therapy for patients with high-stage disease seems to be decreasing.

Borderline mucinous tumors

The first comprehensive report on mucinous borderline tumors appeared in 1973, just prior to the publication of the WHO classification.9 Borderline mucinous tumors are less common than serous borderline tumors in most reports by 20% to over 100%, but in Japan serous and mucinous borderline tumors are equally prevalent.27 In 1988, two basic types of borderline mucinous tumors were delineated: the intestinal type and the endocervical-like (Mullerian) type.76 The endocervical-like type is clinically and pathologically closely related to serous borderline tumors with which it is often mixed (also known as seromucinous borderline tumor and Mullerian borderline mucinous tumor). It accounts for only 5–14% of borderline mucinous tumors25 and has little in common with intestinal-type mucinous tumors. The pure and mixed endocervical-like borderline mucinous tumors have a high association with endometriosis which is the site of origin of the tumors in some instances. The intestinal type is much more common and is the prototypical mucinous borderline tumor. In this discussion, only borderline tumors of the intestinal type will be reviewed.

Mucinous Borderline Tumors of Intestinal Type

Mucinous borderline tumors of intestinal type far outnumber primary invasive mucinous carcinomas. They occur over a very wide age range (9–70 years), with a mean age of 35 years (comparable to that for borderline serous tumors).9 Typically, they produce large multicystic masses (mean diameter, 17 cm) with smooth outer surfaces that may resemble benign mucinous cystadenomas (Figure 18).9 Over 90% are unilateral. This is an important statistic, because bilaterality of a mucinous tumor should always suggest the possibility of a metastatic tumor to the ovaries from the appendix or other gastrointestinal sites, the pancreas or the endocervix, rather than a primary ovarian neoplasm.

The ovarian surface and the cyst linings of borderline mucinous tumors are generally smooth. However, some cysts have a thickened, velvety appearance, and a few have grossly visible papillae. Prominent intracystic and exophytic papillary structures, as are commonly seen in serous and endocervical-like borderline tumors, typically are absent. Solid areas and firm nodules may be seen, usually due to closely packed small cysts tensely filled with mucin or sometimes due to a minor adenofibromatous component. However, such areas must be carefully sampled to rule out invasive tumor, including mural nodules of anaplastic carcinoma or sarcoma. One of the most important aspects of mucinous tumors is their heterogeneous composition. Borderline tumors often contain areas of cystadenoma and noninvasive carcinoma, and occult areas of invasive carcinoma also may coexist (Figure 19). Hence, adequate sampling of mucinous tumors is especially important. As a general rule, a block of tissue for each 1–2 cm of the tumor's maximal dimension should be taken to exclude invasive carcinoma.9 Tumors with high-grade epithelium or questionable invasion may require even more thorough sampling. Because of the large size of most borderline mucinous tumors, even extensive sampling may fail to detect a component of invasive carcinoma on rare occasions.

Histologically, mucinous borderline tumors typically are composed of multiple cysts and glands of various sizes. Small daughter cysts and glandular outpouchings often produce a complex, but generally orderly, pattern (Figure 20). A filigree pattern of intraluminal short papillary infoldings is common (Figure 21). The glands and cysts are lined by a mixture of cell types, including endocervical-, gastric- and goblet-type mucinous cells (Figure 22). Neuroendocrine cells may also be seen. The epithelial cells lining the glands and cysts generally are stratified into no more than two or three layers and have slight-to-moderate nuclear atypia.9 The papillary infoldings typically have thin central stromal cores (Figure 23). Mitotic figures may be easily found. Tangential sections of glands may simulate a pattern of intraglandular bridging or cribriforming, but the presence of a delicate stromal network surrounding each glandular unit indicates the cribriform-like pattern is artefactual (Figure 24).9 Tangential sectioning also produces pseudostratification of epithelial cells. Areas of necrosis and acute inflammation, sometimes of large size, are not uncommon.

For an otherwise typical mucinous cystadenoma to be diagnosed as a borderline tumor, more than minor foci of atypia should be found. The lower limit of atypia for classification as a borderline tumor is, of course, impossible to state with certainty. In one study, low-grade atypia had to involve more than a few high-magnification fields or at least 1% of the sectional area of the tumor to qualify for a diagnosis of borderline tumor; otherwise, the tumor was classified as a mucinous cystadenoma with focal low-grade atypia.77 In practice, most gynecologic pathologists probably allow up to 5%, provided the tumor has been well-sampled and the nuclear atypia is qualitatively, as well as quantitatively, of minor degree.

Tumors with Stromal Microinvasion

In up to 9% of borderline mucinous tumors, one or multiple tiny foci of stromal invasion may be present (Figures 25, 26 and 27).25, 26, 29, 78 The size criteria commonly used for a diagnosis of stromal microinvasion were previously detailed in this article. In most cases, individual microinvasive foci in mucinous tumors are less than 1 or 2 mm.29, 78 The tumor in the microinvasive foci may have several patterns, including: isolated tiny cellular clusters or individual cells surrounded by a clear space (Figure 25); small irregular glands, often with jagged contours, accompanied by a reactive stroma of edema, fibroblastic cells and a variable mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figures 26 and 27); and, strips or nests of epithelium within a small amount of mucin (Figure 28). The latter pattern is difficult, if not impossible in some instances, to distinguish from extruded borderline epithelium from a nearby ruptured gland, especially when accompanied by a mucin granuloma.29, 79, 80 In one study, small foci of confluent glandular or cribriform growth within the stroma were also diagnosed as microinvasion.28 When uncertainty exists, a diagnosis of microinvasion should not be made.

Focal stromal microinvasion in a mucinous borderline tumor of intestinal type. Small clusters of neoplastic epithelial cells with high-grade nuclear atypia in clear spaces are within a slightly edematous stroma. The adjacent cystic mucinous glands show varying degrees of nuclear atypia, ranging from low-grade (borderline) to high-grade (noninvasive carcinoma).

Mucinous borderline tumor of intestinal type. Clusters of epithelial cells with low-grade (borderline) nuclear atypia within mucin are adjacent to a cystic gland lined by borderline mucinous epithelium. While generally diagnosed as stromal microinvasion in a borderline tumor, such changes may have resulted from rupture of a neoplastic gland and extrusion of its epithelium and mucin into the stroma.

We attempt to distinguish microinvasion of borderline epithelium from microinvasive carcinoma.29 In the former, the microinvasive tumor cells in the stroma and the epithelium lining the adjacent glands consist of borderline-type epithelium with low-grade nuclear atypia (Figures 27 and 28). In contrast, microinvasive carcinoma has the histologic features of a diminutive invasive carcinoma. The invasive tumor cells have high-grade nuclear atypia, as do the adjacent glands from which they are believed to originate (Figures 25 and 26).25, 29 Most examples of stromal microinvasion have features of microinvasive carcinoma.29, 79 While some investigators agree with this approach,26 others use the terms microinvasive carcinoma and microinvasive borderline tumor synonymously.28

Pseudomyxoma Peritonei

While pseudomyxoma peritonei was historically thought to be the characteristic pattern of spread of ovarian borderline mucinous tumors of intestinal type, especially those that were ruptured,20, 76 it is now generally agreed that this sequence of events rarely occurs. In the largest series of ruptured Stage I borderline mucinous neoplasms, none was followed by pseudomyxoma peritonei (or discrete metastases) during postoperative intervals of 3–19 years.9 In another large study, one patient with a ruptured Stage Ia borderline tumor with intraepithelial carcinoma died of metastatic tumor, but did not have pseudomyxoma peritonei.25

The preponderance of evidence indicates that pseudomyxoma peritonei almost always results from intraperitoneal spread of a nonovarian adenomatous mucinous neoplasm, most often a ruptured or leaking primary appendiceal mucinous tumor with microscopic features of an adenoma, cystadenoma or villous adenoma or low-grade mucinous neoplasm (Figure 29).81, 82, 83, 84 Synchronous cystic ovarian mucinous tumors with gross and microscopic features suggesting a borderline tumor often are found and may dominate the surgical findings (Figure 30). They usually are discovered intraoperatively before the appendiceal tumor is detected. These ovarian tumors develop secondarily following incorporation into the ovarian parenchyma of peritoneal mucin and neoplastic epithelium deposited on their cortical surfaces.81, 82 They are often bilateral or right-sided, have prominent surface deposits of pseudomyxoma peritonei and contain abundant extracellular mucin dissecting through the ovarian stroma together with mucinous epithelial cysts lined by benign and borderline epithelium with goblet cells (‘pseudomyxoma ovarii’) (Figure 31). Mucin gene overexpression studies, cytokeratin profiles and molecular genetic studies support the conclusion that the appendiceal tumor is the source of pseudomyxoma peritonei and the synchronous ovarian tumors.85 Rarely, origin of pseudomyxoma peritonei is attributable to an ovarian borderline mucinous tumor associated with a mature teratoma.25, 86, 87

Large secondary multicystic mucinous tumor grossly simulating a primary ovarian mucinous tumor resulted from pseudomyxoma peritonei caused by the ruptured primary appendiceal mucinous cystadenoma seen in Figure 29. The opened tumor shows multiple mucin-filled cysts and a large amount of mucinous deposits on its cortical surface (at right).

Tumors with Noninvasive Carcinoma

Small or large areas of noninvasive mucinous carcinoma occur in about 15–55% of otherwise typical borderline mucinous tumors.9, 25, 26 They consist of smoothly contoured glands lined by cells with high-grade nuclear atypia. Often, but not always, the involved glands or cysts show prominent crowding and multilayering of cells, intraluminal micropapillae devoid of central stromal cores, intraglandular bridges or true cribriform structures (Figures 32 and 33).9, 29 Recently, the terms ‘intraglandular carcinoma’ and ‘intraepithelial carcinoma’ have been proposed as alternative designations to noninvasive carcinoma.27, 29 Fortunately, the approach advocated by some of not diagnosing noninvasive carcinoma within a mucinous borderline tumor has largely been abandoned.21, 23

When noninvasive carcinoma is focal or confined to a few widely spaced and clearly noninfiltrative glands or cysts, diagnosis is not a problem (Figure 34). More problematic are those tumors in which multiple closely approximated glands lined by histologically malignant epithelium are separated by only thin strands of unaltered ovarian stroma (Figure 35). In these situations, the distinction between extensive noninvasive carcinoma and adenocarcinoma with an orderly pattern of invasion becomes problematic with low interobserver reproducibility. Recently, it has been proposed that a diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma with ‘expansile invasion’ should be made when a complex, often labyrinthine, pattern of glands or papillae lined by malignant epithelium with minimal or no intervening stroma exceeds an area of 10 mm2 and is at least 3 mm in each of two linear dimensions (Figure 36).25, 26 Others diagnose ‘confluent invasion’ when involved areas are greater than 5 mm in greatest dimension.28 The use of such size limits to distinguish extensive noninvasive carcinoma from well-differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma is, of course, arbitrary and more data are needed to test their validity. Whenever noninvasive carcinoma is encountered, additional sampling is required to exclude areas of overtly invasive carcinoma with an irregularly invasive pattern (ie, ‘destructive stromal invasion,’ ‘infiltrative invasion’) (Figure 37), as it is this pattern that has the most adverse prognosis.29

Extensive noninvasive carcinoma in a mucinous borderline tumor of intestinal type. Closely spaced cystic glands lined by malignant epithelium have very little intervening stroma. Distinction from invasive carcinoma of the expansile type is problematic in such cases, and the size of the involved area has been proposed as the distinguishing criterion.

Prognosis and Treatment

Almost all borderline mucinous tumors of intestinal type are Stage I and have an excellent prognosis following surgical treatment with reported metastatic rates of 0–3% for those without noninvasive carcinoma and 0–7% for those with noninvasive carcinoma.25, 26, 28, 29 In one of the largest reported series of Stage I pure borderline tumors devoid of microinvasion or noninvasive carcinoma, corrected actuarial survival rates were 98% at 5 years and 96% at 10 years.9 More than half of the tumors had been treated solely by unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Some of the fatal tumors were not well sampled and undetected small areas of invasive carcinoma may have been present within these large neoplasms. In more recent studies of pure borderline tumors, all were Stage I (except for a small number with pseudomyxoma peritonei that probably were not primary ovarian tumors), and none metastasized.25, 26, 28

Tumors with noninvasive carcinoma also have a favorable prognosis, although some have metastasized or were at high stage when initially diagnosed.9, 77, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92 Usually they are Stage I tumors, although up to 7.2% of reported cases in one literature review have been Stage II or III.25 According to one literature review, almost 6% of 208 Stage I borderline tumors with noninvasive carcinoma recurred.25 While inadequate sampling with undetected areas of invasive carcinoma or understaging may be explanations for some of these cases, not all examples of clinically malignant behavior of borderline tumors with or without noninvasive carcinoma can be dismissed as diagnostic or staging errors.25, 29

None of the reported borderline tumors with stromal microinvasion or microinvasive carcinoma has metastasized, but the total number of cases is relatively small.25, 26, 28, 29 Moreover, none of the Stage I tumors in three large studies of primary mucinous tumors specifically diagnosed as carcinoma with expansile invasion or confluent invasion metastasized,25, 26, 28 although rare examples of tumors with expansile invasion have behaved aggressively.92

High-stage pure borderline tumors are very uncommon, provided examples of pseudomyxoma peritonei and other metastatic nonovarian tumors are carefully excluded. Unfortunately, the literature contains numerous reports of Stage III borderline-like ovarian mucinous tumors associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei.20, 21, 67, 93 This has led to a falsely high prevalence of advanced-stage disease and an overestimation of the metastatic potential of borderline mucinous tumors. In the absence of pseudomyxoma peritonei, the vast majority of high-stage primary ovarian mucinous tumors contain overtly invasive carcinoma with an infiltrative pattern and almost all are fatal.25, 26, 29

Approach to Diagnostic Terminology

How should mucinous borderline tumors be diagnosed when they contain elements of stromal microinvasion or histologically malignant epithelium? Should noninvasive (intraglandular or intraepithelial) carcinoma be regarded as a form of borderline tumor or as a type of cystadenocarcinoma? While we have argued for the latter approach,9, 29 others prefer the former.25, 26, 28 From a pragmatic perspective, I recommend diagnosing each histologic component and providing a rough estimate of the extent of each. When invasive carcinoma is identified, its grade should be provided. Examples would include the following: borderline mucinous tumor with focal stromal microinvasion; borderline mucinous tumor with multifocal noninvasive carcinoma; and, extensively invasive well-differentiated carcinoma arising in a borderline mucinous tumor.

References

Pickel H, Tamussino K . History of gynecological pathology. XIV. Hermann Joannes Pfannenstiel. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2003;22:310–314.

Abel C, Bandler SW . Gynecological Pathology. A Manual of Microscopic Technique and Diagnosis in Gynecological Practice For Students and Physicians. William Wood & Company: New York, 1901.

Taylor Jr HC . Malignant and semi-malignant tumors of the ovary. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1929;48:204–230.

Munnell EW, Taylor HC . Ovarian carcinoma: a review of 200 primary and 51 secondary cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1949;58:943–959.

Fisher ER, Krieger JS, Skirpan PJ . Ovarian cystoma. Clinicopathological observations. Cancer 1955;8:437–445.

Tamakoshi K, Kikkawa F, Nakashima N, et al. Clinical behavior of borderline ovarian tumors: a study of 150 cases. J Surg Oncol 1997;64:147–152.

FIGO. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Classification and staging of malignant tumours in the female pelvis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1971;50:1–7.

Aure JC, Hoeg K, Kolstad P . Clinical and histologic studies of ovarian carcinoma: long-term follow-up of 990 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1971;37:1–9.

Hart WR, Norris HJ . Borderline and malignant mucinous tumors of the ovary. Histologic criteria and clinical behavior. Cancer 1973;31:1031–1045.

Kottmeier HL . Problems relating to classification and stage-grouping of malignant tumors in the female pelvis. In: Eleventh Annual Clinical Conference on Cancer, 1996. University of Texas MD Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute, Yearbook Medical Publishers, Inc.: Chicago, 1966, pp 17–32.

Nieminen U, Purola E . Stage and prognosis of ovarian cystadenocarcinomas. Acta Obstet Gynec Scand 1970;49:49–55.

Serov SF, Scully RE, Sobin LH . International Histologic Classification of Tumours. No. 9. Histological Typing of Ovarian Tumours. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1973.

Scully RE, Sobin LH . Histologic Typing of Ovarian Tumors, 2nd edn. In: World Health Organization International Histological Classification of Tumors. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1999.

Santesson L, Kottmeier HL . General classification of ovarian tumors. In: Gentil F, Junqueira AC (eds). Ovarian Cancer (UICC Monograph Series). Springer-Verlag: New York, 1968, pp 1–8.

Hart WR . Ovarian epithelial tumors of borderline malignancy (carcinomas of low malignant potential). Hum Pathol 1977;8:541–549.

Katzenstein AA, Mazur MT, Morgan TE, et al. Proliferative serous tumors of the ovary: histologic features and prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol 1978;2:339–355.

Nikrui N . Survey of clinical behavior of patients with borderline epithelial tumors of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 1981;12:107–119.

Scully RE . Ovarian tumors: a review. Am J Pathol 1977;87:686–720.

Scully RE . Common epithelial tumors of borderline malignancy (carcinomas of low malignant potential). Bull Cancer (Paris) 1982;69:228–238.

Russell P . The pathological assessment of ovarian neoplasms. I. Introduction to the common ‘epithelial’ tumours and analysis of benign ‘epithelial’ tumours. Pathol 1979;11:5–26.

Russell P, Merkur H . Proliferating ovarian ‘epithelial’ tumours: a clinico-pathological analysis of 144 cases. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol 1979;19:45–51.

Leitao Jr MM, Boyd J, Hummer A, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of early-stage sporadic ovarian carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:147–159.

Russell P . Surface epithelial–stromal tumors of the ovary. In: Kurman RJ (ed). Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract, 4th edn. Springer-Verlag: New York, 1994, pp 705–782.

Tavassoli FA, Devilee P (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics. Tumours of the Breast and Female Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, 2003.

Lee KR, Scully RE . Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 196 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas, including an evaluation of 11 cases with ‘pseudomyxoma peritonei’. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1447–1464.

Rodriguez IM, Prat J . Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 75 borderline tumors (of intestinal type) and carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:139–152.

Scully RE, Young RH, Clement PB . Tumors of the ovary, maldeveloped gonads, fallopian tube, and broad ligament. In: Rosai J (ed). Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Third Series, Fascicle 23. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: Washington, DC, 1998.

Riopel MA, Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ . Evaluation of diagnostic criteria and behavior of ovarian intestinal-type mucinous tumors: atypical proliferative (borderline) tumors and intraepithelial, microinvasive, invasive, and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:617–635.

Hoerl HD, Hart WR . Primary ovarian mucinous cystadenocarcinomas: a clinicopathologic study of 49 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:1449–1462.

Kennedy AW, Hart WR . Ovarian papillary serous tumors of low malignant potential (serous borderline tumors): a long term follow-up study, including patients with microinvasion, lymph node metastasis, and transformation to invasive serous carcinoma. Cancer 1996;78:278–286.

Segal GH, Hart WR . Ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential (serous borderline tumors): the relationship of exophytic surface tumor to peritoneal ‘implants’. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:577–583.

Goldblum JR, Hart WR . Localized and diffuse mesotheliomas of the genital tract and peritoneum in women: a clinicopathologic study of nineteen true mesothelial neoplasms, other than adenomatoid tumors, multicystic mesotheliomas and localized fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1124–1137.

Kao GF, Norris HJ . Cystadenofibromas of the ovary with epithelial atypia. Am J Surg Pathol 1978;2:357–363.

Bostwick DG, Tazelaar HD, Ballon SC, et al. Ovarian epithelial tumors of borderline malignancy: a clinical and pathologic study of 109 cases. Cancer 1986;58:2052–2065.

Lage JM, Weinberg DS, Huettner PC, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of nuclear DNA content in ovarian tumors. Association of ploidy with tumor type, histologic grade, and clinical stage. Cancer 1992;69:2668–2675.

Burks RT, Sherman ME, Kurman RJ . Micropapillary serous carcinoma of the ovary: a distinctive low-grade carcinoma related to serous borderline tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1319–1330.

Seidman JD, Kurman RJ . Subclassification of serous borderline tumors of the ovary into benign and malignant types: a clinicopathologic study of 65 advanced stage cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:1331–1345.

Prat J, de Nictolis M . Serous borderline tumors of the ovary: a long-term follow-up study of 137 cases, including 18 with a micropapillary pattern and 20 with microinvasion. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1111–1128.

Deavers MT, Gershenson DM, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Micropapillary and cribriform patterns in ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential: a study of 99 advanced stage cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1129–1141.

Eichhorn JH, Bell DA, Young RH, et al. Ovarian serous borderline tumors with micropapillary and cribriform patterns: a study of 40 cases and comparison with 44 cases without these patterns. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:397–409.

Hart WR . Pathology of malignant and borderline (low malignant potential) epithelial tumors of ovary. In: Coppleson M, Monaghan JM, Morrow CP, Tattersall MHN (eds). Gynecologic Oncology, 2nd edn, Chapter 55. Churchill-Livingstone: Edinburgh, 1992, pp 863–887.

Bell DA, Scully RE . Ovarian serous borderline tumors with stromal microinvasion: a report of 21 cases. Hum Pathol 1990;21:397–403.

Tavassoli FA . Serous tumor of low malignant potential with early stromal invasion (serous LMP with microinvasion). Mod Pathol 1988;1:407–414.

Hanselaar AGJM, Vooijs GP, Mayall B, et al. Epithelial markers to detect occult microinvasion in serous ovarian tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1993;12:20–27.

Mooney J, Silva E, Tornos C, et al. Unusual features of serous neoplasms of low malignant potential during pregnancy. Gynecol Oncol 1997;65:30–35.

Buttin BM, Herzog TJ, Powell MA, et al. Epithelial ovarian tumors of low malignant potential: the role of microinvasion. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:11–17.

McKenney JK, Balzer BL, Longacre TA . Ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential with stromal microinvasion: a clinicopathologic study of 36 cases. Mod Pathol 2004;17:205A–206A.

Bell DA, Weinstock MA, Scully RE . Peritoneal implants of ovarian serous borderline tumors: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer 1988;62:2212–2222.

Rollins SE, Young RH, Bell DA . Autoimplants involving serous borderline tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Mod Pathol 2004;17:213A.

Gilks CB, Alkushi A, Yue JJW, et al. Advanced-stage serous borderline tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathological study of 49 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;22:29–36.

Bell KA, Smith Sehdev AE, Kurman RJ . Refined diagnostic criteria for implants associated with ovarian atypical proliferative serous tumors (borderline) and micropapillary serous carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:419–432.

Silva EG, Kurman RJ, Russell P, et al. Symposium: ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1996;15:281–302.

Malpica A, Deavers MT, Gershenson D, et al. Serous tumors involving extra-abdominal/extra-pelvic sites after the diagnosis of an ovarian serous neoplasm of low malignant potential. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:988–996.

Silva EG, Tornos C, Zhuang Z, et al. Tumor recurrence in stage I ovarian serous neoplasms of low malignant potential. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1998;17:1–6.

Moore WF, Bentley RC, Berchuck A, et al. Some mullerian inclusion cysts in lymph nodes may sometimes be metastases from serous borderline tumors of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:710–718.

Bell DA, Scully RE . Serous borderline tumors of the peritoneum. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:230–239.

Biscotti CV, Hart WR . Peritoneal serous micropapillomatosis of low malignant potential (serous borderline tumors of the peritoneum): a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:467–475.

Zanotti KM, Hart WR, Kennedy AW, et al. Allelic imbalance on chromosome 17p13 in borderline (low malignant potential) epithelial ovarian tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1999;18:247–253.

Sieben NLG, Kolkman-Uljee SM, Flanagan AM, et al. Molecular genetic evidence for monoclonal origin of bilateral ovarian serous borderline tumors. Am J Pathol 2003;162:1095–1101.

Diebold J, Seemuller F, Lohrs U . K-RAS mutations in ovarian and extraovarian lesions of serous tumors of borderline malignancy. Lab Invest 2003;83:251–258.

Tan LK, Flynn SD, Carcangiu ML . Ovarian serous borderline tumors with lymph node involvement. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:904–912.

Shiraki M, Otis CN, Donovan JT, et al. Ovarian serous borderline epithelial tumors with multiple retroperitoneal nodal involvement: metastasis or malignant transformation of epithelial glandular inclusions? Gynecol Oncol 1992;46:255–258.

Leake JF, Rader JS, Woodruff JD, et al. Retroperitoneal lymphatic involvement with epithelial ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. Gynecol Oncol 1991;42:124–130.

Rice LW, Berkowitz RS, Mark SD, et al. Epithelial ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy. Gynecol Oncol 1990;39:195–198.

Rota SM, Zanetta G, Ieda N, et al. Clinical relevance of retroperitoneal involvement from epithelial ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1999;9:477–480.

Clement PB, Young RH, Oliva E, et al. Hyperplastic mesothelial cells within abdominal lymph nodes: mimic of metastatic ovarian carcinoma and serous borderline tumor—a report of two cases associated with ovarian neoplasms. Mod Pathol 1996;9:879–886.

Koern J, Trope CG, Abeler VM . A retrospective study of 370 borderline tumors of the ovary treated at the Norwegian Radium Hospital from 1970 to 1982: a review of clinicopathologic features and treatment modalities. Cancer 1993;71:1810–1820.

Lee KR, Castrillon DH, Nucci MR . Pathologic findings in eight cases of ovarian serous borderline tumors, three with foci of serous carcinoma, that preceded death or morbidity from invasive carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2001;20:329–334.

Seidman JD, Kurman RJ . Ovarian serous borderline tumors: a critical review of the literature with emphasis on prognostic indicators. Hum Pathol 2000;31:539–557.

Sehdev AES, Sehdev PS, Kurman RJ . Noninvasive and invasive micropapillary (low-grade) serous carcinoma of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 135 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:725–736.

Staebler A, Heselmeyer-Haddad K, Bell K, et al. Micropapillary serous carcinoma of the ovary has distinct patterns of chromosomal imbalances by comparative genomic hybridization compared with atypical proliferative serous tumors and serous carcinomas. Hum Pathol 2002;33:47–59.

Katabuchi H, Tashiro H, Cho KR, et al. Micropapillary serous carcinoma of the ovary: an immunohistochemical and mutational analysis of p53. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1998;17:54–60.

Slomovitz BM, Caputo TA, Gretz III HF, et al. A comparative analysis of 57 serous borderline tumors with and without a noninvasive micropapillary component. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:592–600.

Kempson RL, Hendrickson MR . Ovarian serous borderline tumors: the citadel defended (Editorial). Hum Pathol 2000;31:525–526.

Barnhill DA, Kurman RJ, Brady MF, et al. Preliminary analysis of the behavior of stage I ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:2752–2756.

Rutgers JL, Scully RE . Ovarian müllerian mucinous papillary cystadenomas of borderline malignancy: a clinicopathologic analysis. Cancer 1988;61:340–348.

Guerrieri C, Hogberg T, Wingren S, et al. Mucinous borderline and malignant tumors of the ovary. A clinicopathologic and DNA ploidy study of 92 cases. Cancer 1994;74:2329–2340.

Nayar R, Siriaunkgul S, Robbins KM, et al. Microinvasion in low malignant potential tumors of the ovary. Hum Pathol 1996;27:521–527.

Khunamornpong S, Russell P, Dalrymple JC . Proliferating (LMP) mucinous tumors of the ovaries with microinvasion: morphologic assessment of 13 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1999;18:238–246.

Lee HI, Jun S-Y, Ro JY, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria in primary ovarian mucinous tumors with an emphasis on the significance of microinvasion. Mod Pathol 2004;17:201A.

Young R, Gilks B, Scully R . Mucinous tumors of the appendix associated with mucinous tumors of the ovary and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinicopathologic analysis of 22 cases supporting an origin in the appendix. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:415–429.

Prayson RA, Hart WR, Petras RE . Pseudomyxoma peritonei: a clinicopathologic study of 19 cases with emphasis on site of origin and nature of associated ovarian tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:591–603.

Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ, Zahn CM, et al. Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women: a clinicopathologic analysis of 30 cases with emphasis on site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to ovarian mucinous tumors of low malignant potential. Hum Pathol 1995;26:509–524.

Misdraji J, Yantiss RK, Graeme-Cook FM, et al. Appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a clinicopathologic analysis of 107 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:1089–1103.

O'Connell JT, Hacker CM, Barsky SH . MUC2 is a molecular marker for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod Pathol 2002;15:958–972.

Ronnett BM, Seidman JD . Mucinous tumors arising in ovarian mature cystic teratomas: relationship to the clinical syndrome of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:650–657.

McKenney JK, Soslow RA, Longacre TA . Mucinous neoplasms arising in mature teratomas: a clinicopathologic study of ovarian and sacrococcygeal tumors. Mod Pathol 2004;17:206A.

Chaitin BA, Gershenson DM, Evans HL . Mucinous tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic study of 70 cases. Cancer 1985;55:1958–1962.

Kikkawa F, Kawai M, Tamakoshi K, et al. Mucinous carcinoma of the ovary: clinicopathologic analysis. Oncology 1996;53:303–307.

Sumithran E, Susil BJ, Looi LM . The prognostic significance of grading in borderline mucinous tumors of the ovary. Hum Pathol 1988;19:15–18.

Watkin W, Silva EG, Gershenson DM . Mucinous carcinoma of the ovary: pathologic prognostic factors. Cancer 1992;69:208–212.

Ludwick CL, Gilks CB, Yaziji H, et al. Aggressive behavior of stage 1 ovarian mucinous tumors without destructive stromal invasion. Mod Pathol 2004;17:205A.

Kliman L, Rome RM, Fortune DW . Low malignant potential tumors of the ovary: a study of 76 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1986;68:338–344.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mrs Patricia Matkovic for her secretarial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hart, W. Borderline epithelial tumors of the ovary. Mod Pathol 18 (Suppl 2), S33–S50 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800307

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800307

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Salpingo-oophorectomy versus cystectomy in patients with borderline ovarian tumors: a systemic review and meta-analysis on postoperative recurrence and fertility

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2021)

-

Bioinformatics analysis of gene expression profile of serous ovarian carcinomas to screen key genes and pathways

Journal of Ovarian Research (2020)

-

FKBPL-based peptide, ALM201, targets angiogenesis and cancer stem cells in ovarian cancer

British Journal of Cancer (2020)

-

Linked Hexokinase and Glucose-6-Phosphatase Activities Reflect Grade of Ovarian Malignancy

Molecular Imaging and Biology (2019)

-

The impact of clinicopathologic and surgical factors on relapse and pregnancy in young patients (≤40 years old) with borderline ovarian tumors

BMC Cancer (2018)