Abstract

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn (NSJ) is a benign, congenital hamartoma that often presents at birth, appears to regress in childhood, and grows during puberty, suggesting possible hormonal control. We studied 18 cases of NSJ from children and adults for immunohistochemical evidence of androgen receptor expression. The lesions were evaluated for location and pattern of immunostaining, and these findings were compared between age groups, sexes, and to androgen receptor expression in normal skin. Androgen receptor positivity was seen in the sebaceous glands, in eccrine glands with and without apocrine change, and rarely in keratinocytes in the sebaceous nevi. There were no significant differences in staining location or pattern between the age groups or sexes. Normal skin showed similar staining in the sebaceous glands but did not show staining of the eccrine glands or keratinocytes. Androgen receptors are present in all epithelial components of NSJ, but there is no change in androgen receptor expression during puberty.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn (NSJ) is a hamartomatous tumor composed of benign epithelial components including sebaceous glands, epithelium, and eccrine glands, often with apocrine change. In newborn infants, NSJ often appear as slightly verrucous, yellowish hairless plaques. In children, these tumors are well-circumscribed, flat, waxy yellow-tan or yellow-orange, often hairless lesions and are much less prominent than at birth. During puberty, they usually enlarge and become elevated, verrucous, or nodular and may appear brown (1, 2). In late childhood and adulthood, there is a significant risk of developing a secondary tumor, the most common of which are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and basal cell carcinoma (1, 3). Myriad other cutaneous appendageal neoplasms have also been reported to arise within NSJ.

Androgen receptors (AR) are nuclear ligand–dependent transcription factors of the steroid superfamily that bind testosterone and dihydroxytestosterone (4). AR have been identified in normal cutaneous structures and in some epithelial tumors. In normal skin, AR have been localized to sebocytes and to some dermal papillae in anagen and telogen hair follicles (5). They are thought to play a role in pilosebaceous development during puberty (6). Immunohistochemical studies have located androgen receptors in sebaceous tumors, including adenomas, carcinomas, and nevi, as well as in chondroid syringomas and focally in basal cell carcinomas (7, 8).

Because of the prominence of NSJ in the neonatal period, relative quiescence in childhood, and increased growth during puberty, as well as the androgen receptor activity previously reported in sebaceous neoplasms, we were interested in the possible role of androgen receptors in the evolution of NSJ. Specifically, our interest was in the following: what cutaneous structures contain AR and in what distribution are they present within these lesions, does AR expression vary by age or sex, and is AR expression different from that in normal skin?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

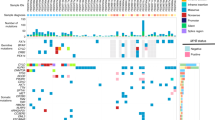

Eighteen cases of NSJ were obtained from the surgical pathology files of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Department of Pathology. The patients ranged in age from 8 to 41, with 7 females and 11 males. All lesions were on the head or neck. Four cases of normal skin from the head or neck containing sebaceous glands were also examined as external controls. All specimens were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded. Routine hematoxylin-eosin–stained slides were reviewed, and immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-μm-thick sections. Sections were deparaffinized and underwent antigen retrieval by heat treatment in DAKO Target Retrieval solution (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) for 20 minutes. Prediluted monoclonal mouse antibodies corresponding to amino acids 299 through 315 of the human androgen receptor were applied using the Immunocruz Staining System (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) as described elsewhere (8). The tissue was allowed to incubate with the primary antibody for 2 hours and then with the biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 minutes. The signal was detected with a 3,3′-diaminobenzidene in chromogen solution with Imidazole-HCl buffer at pH 7.5 (DAKO liquid 3,3′-diaminobenzidine large-volume substrate-chromogen system) with brown staining at the site of antibody binding. AR positivity was defined as strong nuclear staining, easily observed at scanning magnification. The percentage of positive nuclei within sebaceous glands, eccrine glands, and keratinocytes was scored from 0–4 using the following scheme: 0–5% = 0, 5–25% = 1, 26–50% = 2, 51–75% = 3, and 76–100% = 4 (Table 1). Adjacent normal sebaceous glands served as positive internal controls and adjacent normal skin without sebaceous glands served as negative internal controls. The specimens were analyzed for site, pattern, and percentage of immunostaining.

RESULTS

All (18/18) cases of NSJ contained hyperplastic sebaceous glands with strong nuclear AR immunostaining. The pattern of staining in the sebaceous glands was primarily basilar, with extension of staining toward the center of the sebaceous glands (Fig. 1). The percentage of staining sebocytes ranged from 26–50% to >75% (Table 2). There was no difference in staining distribution or extent between males and females or between children and adults (Tables 2 and 3). Fifteen (15/18) cases contained eccrine glands within the sections examined, and 9 of these 15 cases showed apocrinization of the eccrine glands (or ectopic apocrine glands). There was patchy immunostaining of the eccrine/apocrine glands, whereas the ductular epithelium was nonimmunoreactive (Fig. 2). The percentage of immunoreactive eccrine/apocrine cells ranged from <5% to 26–50%. There was no difference in eccrine/apocrine staining based on age or sex. Four of 18 cases showed nuclear positivity in keratinocytes, with a predominant basilar staining pattern, and a percentage of staining cells ranging from <5% to 26–50% (Fig. 3). Again, there was no difference in keratinocyte immunoreactivity between males and females or children and adults. One case contained a secondary neoplasm, a basal cell carcinoma, which was nonimmunoreactive. Other cutaneous appendage neoplasms were not detected in any of the cases selected for inclusion in the study.

Normal skin showed similar staining of sebaceous glands, with all cases showing nuclear positivity in sebocytes; however, the percentage of positive sebocytes was less than that seen in the sebaceous nevi (Table 3). The pattern of sebocyte staining was similar, with a predominance of staining in the basal layer. In addition, there was no staining of eccrine glands or ducts, nor of the keratinocytes in the normal skin. Apocrine glands were not present in any of the sections of normal skin examined, as these sections were taken from normal skin on the head and neck.

DISCUSSION

We examined a series of NSJ removed from patients of both sexes and all ages with antibodies directed against androgen receptors. Androgen receptors were present within the nuclei of sebocytes in NSJ from all patients studied. There were no differences in the quality of the staining pattern. However, in all cases of NSJ, the extent of the staining within sebaceous glands was far more impressive than that seen in sebaceous glands from normal control subjects. Of additional interest, eccrine/apocrine glands demonstrated patchy labeling with anti-androgen receptor antibodies in the majority of cases of NSJ. No such staining was seen in eccrine or apocrine glands from the control subjects. Similarly, basal-layer keratinocytes demonstrated anti–androgen receptor antibody staining in 22% of patients with NSJ, but not in any of the control patients.

The data suggest several interesting possibilities about the pathogenesis and evolution of NSJ and its relationship to androgens. As expected, these lesions appear to be under direct hormonal regulation, demonstrating high levels of androgen receptor antibodies within the proliferative components of the hamartomas. It is somewhat surprising that the levels of androgen receptors appear to be up-regulated at all ages. Thus, increased androgen sensitivity may be present within this lesional skin at all times during life.

In addition, the androgen responsiveness does not appear to be limited to sebaceous glands, as it is in normal skin, but appears to be present within other epithelial components of the lesional skin as well. Thus, the clinical course of these lesions could be explained by the exposure of cells in the lesional skin to circulating levels of androgens. The response of epithelial structures within NSJ may be augmented compared with that of surrounding nonlesional skin. When androgens are present, the epidermis becomes hyperproliferative, sebaceous glands markedly enlarge, and changes develop in the eccrine apparatus. Similar changes within sebaceous glands have been noted in patients with elevated circulating androgen levels and in patients using anabolic-androgenic steroids (9, 10). However, the verrucous epidermal hyperplasia and “apocrinization” of eccrine glands present in many NSJ have never been adequately explained. Perhaps the increased androgen receptors in these structures play a role in the changes observed within these structures in NSJ.

It is also interesting that the degree of androgen receptor expression in NSJ does not appear to correlate with age. Increased levels of serum androgens are present in neonates and during puberty (11, 12). It might have been expected that there would be different degrees of AR expression during these times than in more hormonally quiescent periods of life. This was not demonstrated in our series. It is possible that the technique we employed is not sensitive enough to detect quantitative differences. Alternatively, it is possible that lesional skin in NSJ has constitutively increased amounts of the receptors that are not under the usual direct control and regulation of circulating serum androgens.

This study has attempted to assess the relationship between androgen receptor expression and the clinical course of NSJ. We have demonstrated significantly increased androgen receptors in sebocytes and other epithelial components within lesional skin of NSJ in patients of all ages. We believe that NSJ represent a hamartomatous proliferation of cutaneous elements that may be constitutively hypersensitive to the effects of circulating androgens. Further studies, perhaps using cell cultures derived from components of NSJ, are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

References

Mehregan AH, Pinkus H . Life history of organoid nevi. Arch Dermatol 1965; 91: 574–588.

Morioka S . The natural history of nevus sebaceus. J Cutan Pathol 1985; 12: 200–213.

Weng CJ, Tsai YC, Chen TJ . Jadassohn’s nevus sebaceous of the head and face. Ann Plast Surg 1990; 25: 100–102.

Brinkmann AO, Blok LJ, de Ruiter PE, Doesburg P, Steketee K, Berrevoets CA, et al. Mechanisms of androgen receptor activation and function. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1999; 69: 307–313.

Choudry R, Hodgins MB, Van der Kwast TH, Brinkmann AO, Boersma WJ . Localization of androgen receptors in human skin by immunohistochemistry: implications for the hormonal regulation of hair growth, sebaceous glands and sweat glands. J Endocrinol 1992; 133: 467–475.

Rosenfield RL, Deplewski D . Role of androgens in the developmental biology of the pilosebaceous unit. Am J Med 1995; 98: 80S–88S.

Shikata N, Kurokawa I, Andachi H, Tsubura A . Expression of androgen receptors in skin appendage tumors: an immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol 1995; 22: 149–153.

Bayer-Garner IB, Givens V, Smoller B . Immunohistochemical staining for androgen receptors: a sensitive marker of sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol 1999; 21: 426–431.

Thiboutot D, Gilliland K, Light J, Lookingbill D . Androgen metabolism in sebaceous glands from subjects with and without acne. Arch Dermatol 1999; 135: 1041–1045.

Scott MJ 3rd, Scott AM . Effects of anabolic-androgenic steroids on the pilosebaceous unit. Cutis 1992; 50: 113–116.

Albertsson-Wikland K, Rosberg S, Lannering B, Dunkel L, Selstam G, Norjavaara E . Twenty-four hour profiles of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, testosterone, and estradiol levels: a semilongitudinal study throughout puberty in healthy boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82: 541–549.

Ilondo MM, Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx M, Vlietinck R, Pizarro M, Malvaux P, Eggermont E, et al. Plasma androgens in children and adolescents. Part I: control subjects. Horm Res 1982; 16: 61–77.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hamilton, K., Johnson, S. & Smoller, B. The Role of Androgen Receptors in the Clinical Course of Nevus Sebaceus of Jadassohn. Mod Pathol 14, 539–542 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880346

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880346