Abstract

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma is a rare locally aggressive vascular tumor of the skin, deep soft tissue, and bone in children, characterized by infiltrating nodules and sheets of spindle cells, and unmistakable resemblance to Kaposi’s sarcoma. More than 60 patients with such tumor have been reported so far, and while many have died as a result of extensive disease and severe coagulopathy, the long-term biologic behavior of this tumor remains undetermined. We describe five patients with kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and a mean follow-up of 19 years, ranging from 8 to 35 years. This report emphasizes on the importance of cutaneous lesions being the most commonly affected site, but also for its clinical diversity. Early diagnosis is possible even for a small skin lesion, which may be critical for the treatment of a potentially fatal deep-seated extensive tumor. All five patients are well, and three of them with persistent vascular tumor, which has carried two patients from childhood to adult. Although the behavior of this tumor might have been modified by radiation or interferon in three patients, this series indicates that kaposiform hemangioendothelioma is incapable of metastasis, despite a protracted course of many decades with no tendency for spontaneous regression.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Although a relatively rare condition, the increasing number of reports on kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KH) reflects a better recognition of this vascular tumor of deep soft tissue and skin in infants and children, often complicated by Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17). The use of the term “kaposiform” relates to its unmistakable resemblance to Kaposi’s sarcoma, assumed by the compact spindled tumor cells characterized by the formation of slit-like lumen (2, 3, 6, 13, 14, 17). The designation of “hemangioendothelioma” implies the uncertainty regarding the biologic behavior of such tumor, situated somewhere between hemangioma and angiosarcoma (7, 14, 15, 17). KH may be locally very extensive and aggressive, but has not shown any metastatic potential, though death has resulted from severe coagulopathy (6, 14, 17). However, the long-term natural history of such vascular tumor remains uncertain, and for most reported examples the follow-up was unknown or limited (13, 16, 17). Because many patients with retroperitoneal involvement were severely affected and died such tumor distribution has been emphasized (4, 6, 14, 17). In fact, only about 18% of reported patients demonstrated retroperitoneal tumor, while a third of the patients showed involvement of the trunk or the limbs, and cutaneous lesions were observed in nearly 75% of the reported cases (1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15, 16, 17). We describe five patients with KH stressing on the importance of cutaneous manifestations related to its diversity, to the early diagnosis and therapy, and the tumor behavior over a long follow-up period ranging from 8 to 35 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A complete medical record is available in all patients since their presentation, except for Patient 4, whose early records are lost. In all cases, histologic sections from surgical specimens were examined, and tissues blocks were available for immunohistochemistry of vimentin (DAKO, 1:100), factor VIII (DAKO, 1:100), CD31 (DAKO, 1:50), CD34 (DAKO, 1:20), Ulex EA-1 lectin (UEA-1, Vector Laboratories, Ca, 1:200), and smooth muscle actin (DAKO, 1:200). None of the patient was tested for human immunodeficiency virus serology.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1

This case was previously reported, and only the cutaneous lesions and the follow-up are described here (11). This 5-month-old boy presented with a small skin nodule on the right antecubital fossa, and the diagnosis of hemangioma and hemangiopericytoma was made on the excision. He returned a year later with a swollen right forearm, and extensive soft tissue tumor infiltration including the distal radius and ulna (Fig. 1). Only two small cutaneous purplish nodules, each of less than 1 cm, were apparent at the old biopsy site and other on the distal lateral aspect. An above-elbow amputation was performed for the uncertainty regarding the nature of the tumor, and for a severe Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. The boy was rehabilitated with an artificial limb. He has been disease-free for 16 years of follow-up.

Patient 2

This 7-month-old boy was hospitalized in 1986 for a severe urinary tract infection, but recovered on antibiotics. The uro-cystogram was normal and no skin lesion was noted then. Three months later, an enlarging purplish plaque was noted on the left subcostal skin, and a 4 cm subcutaneous mass was shown on ultrasonography with no internal organ involved. The irregular tumor in the rectus muscle found at surgery was excised en block, for the per-operative diagnosis of hemangiopericytoma. The surgical skin defect was repaired with a Dacron graft. The wound healed well, and there was no recurrence after 14 years follow-up.

Patient 3

At birth in October 1992, a tinted papule was noted in this baby girl’s right thigh, which turned to a larger deep crimson plaque a few months later (1). An infantile congenital hemangiopericytoma was reported on the biopsy. The surgeon felt the lesion was extensive and complete excision was not feasible. A second opinion from two consultants proffered the diagnosis of tufted angioma, believing that the tumor was superficial. A magnetic resonance imaging in March 1993 revealed a 5 cm tumor with poorly defined margins in the adductor compartment of the proximal right thigh, not involving the femur and the anterior compartment. The diagnosis was rectified to KH. She developed a Kasabach-Merritt syndrome in April, and interferon therapy was instituted for 5 months. The clinical response was good, but the tumor size remained unchanged. In February 1995, the cutaneous plaque began to regress, and a tumor reducing in size was confirmed by imaging. The initial restriction of thigh movement resolved with regular physiotherapy. The skin discoloration incompletely faded, but there has not been tumor growth after 8 years.

Patient 4

This 39-year-old woman gave a history of “arm infection” at the age of 5 when she presented with a fracture of the right humerus, which was treated conservatively. In the subsequent years, she experienced episodic pain at the same site, but no specific therapy was given. She was first seen by the orthopedic surgeon at the age of 14, and a radiologic lytic lesion was seen in the distal right humerus, which was interpreted as an osteomyelitis. However, the surgical exploration revealed no pus, and cultures were sterile. Similar periodic pain and supportive therapy were recorded on subsequent years. At 29-year-old, serial X-rays demonstrated progressive destruction of the right humerus, and a second pathologic fracture (Fig. 2A). A new lytic lesion in the proximal radius was also demonstrated. Several courses of antibiotics were administered, but these did not prevent progression of the lesions. This time the fracture was surgically treated, but again exploration failed to demonstrate a specific lesion. The pathology slides from these two past operations cannot be traced for review. An iliac bone graft was performed, but this graft gradually disappeared over several months. Attempt to promote union by applying hydroxyapatite to the fracture also failed. In 1993, a vascularized fibular graft shown to be viable by bone scan also later disappeared (Fig. 2B). Repeated cultures and scan remained negative. In June 1994 at the age of 33, a small bluish skin nodule appeared for the first time over the site of bone lesions. The excision was first diagnosed tufted angioma, then corrected to KH. The patient has declined any further active therapy. She has been regularly followed, and no new skin lesion has since appeared.

Patient 5

This 23-year-old man showed at birth a small “hemangioma” on the left thigh, but he was not brought to medical attention until he was 6 years old, as the lesion grew larger, but no specific therapy was given. By the age of 10, the tumor involved the entire left limb and buttock. At the age of 14, the limb showed severe lymphedema and discoloration, and on imaging the tumor extended close to the urinary bladder (1). He received a 6-week course of interferon for Kasabach-Merritt’s syndrome, but the response was only partial. A year later, reconstructive surgery was performed for severe hyperextension, thought to contribute to the lymphedema. At that time, a skin excision reported the condition as proliferative cutaneous angiomatosis, with no cellular nodules seen (1). At 16 years old, he was in good health, but the tumor remained unchanged and required no specific therapy. He then was treated with Chinese herbal medicine for 4 years, resulting in gradual resolution of lymphedema but not of the skin discoloration. At 21, the leg was amputated for rehabilitation with an artificial leg. There has been no new tumor growth.

PATHOLOGY

Grossly, the cutaneous lesion in all five cases showed a purplish to crimson discoloration that was reminiscent of a vascular tumor, though their size varies from small nodule to plaques, and to massive hemangiomatous tumor as in Patients 1 or 5. The paucity of small cutaneous nodules in Patients 1 and 4 markedly contrasted with the extensive subcutaneous and deep soft tissue lesions. The marked variation of the tumor distribution and size in the deep soft tissue in all five cases were demonstrated either from the surgical specimen, or from the organ imaging techniques. It was important to adequately sample the tumor tissue for histologic diagnosis.

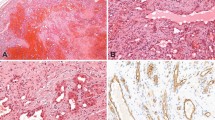

In all five patients, the important microscopic features leading to the diagnosis included the tumor hypercellularity, the spindle cells growing in sheets and nodules or large confluent vascular masses focally with a “cannon-ball” pattern (Fig. 3), and the spindled tumor cells exhibiting the vasoformative slit-like lumen, reminiscent of Kaposi’s sarcoma (Fig. 4). In Cases 1 and 2, tumor nodules were sparse in the dermis, but were distributed extensively in the subcutis. Bone involvement was observed in Cases 1 and 4. Focal broad fibrosis dividing the cellular tumor was most prominent in Patients 1, 2, and 4, but inconspicuous in the others. Similarly lymphangiomatosis was prominent in Cases 3 and 5, but inconspicuous or absent in the other patients (Fig. 5). Apart from the Kaposi-like areas with microhemorrhages, elsewhere the tumor cell exhibited distinctly gaped and rounded vascular lumen. In Patient 5, who received a course of interferon followed by Chinese herbal medicine for 5 years before amputation, the typical tumor nodules were only few on microscopy. In this case, most of the remaining skin, deep soft tissue, and bone showed hyalinized stroma with heavy hemosiderin deposition and collapsed small vessels, reminiscent of regressed tufted angioma (Fig. 6). The tumor also involved a few axillary lymph nodes in Patient 1 (11). For all cases, the tumor cells showed immunoreactivity to vimentin, C31, CD34, and UEA-1 lectin, but variable or equivocal staining for Factor VIII. In Cases 1 and 2, the tumor was completely removed by surgery, while most of the tumor remained in the other patients.

DISCUSSION

The variety of initial diagnosis proffered in these five patients, which included hemangioma, angiomatosis, hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma reflected the readily recognized vascular nature of KH, but also the uncertainty regarding its biologic behavior. Such an initial misdiagnosis is also reflected in the literature, and in part due to unfamiliarity with this rare condition, a skin biopsy not representative of a deep-seated lesion, or biopsy interpreted without the full knowledge of the extent of the tumor (1, 7, 9, 11, 17). The increasing number of reported cases suggests that KH is a better recognized condition, and may not be as rare (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 17).

The cutaneous appearance of KH is generally not distinctive, apart from the extensive “port wine” hemangiomatous presentation. The diagnosis rests on the histology, and on its correlation with clinical features, in particular the depth of the lesion. The vasoformative spindle cells with slit-like lumen, microhemorrhages, and fascicular arrangement constitute its unmistakable resemblance to Kaposi’s sarcoma (17). However, all five patients also showed a gaped vascular lumen, large coalescent nodules, broad fibrosis with scanty inflammatory cells, deep extension to soft tissue and bone, which all set them apart from Kaposi’s sarcoma (13, 16, 17). The irregular tumor masses with uncanalized spindle cells distinguish KH from solitary juvenile hemangioma, cellular hemangioma of infancy, and multiple hemangiomas (16, 17). Spindle cell hemangioendothelioma is a small skin lesion with focal resemblance to KH, but also features cavernous spaces, thrombosis, and calcospherules not seen in KH (11, 17). Angiosarcoma differs from KH by the pleomorphic and mitotically active tumor cells (17).

The cutaneous lesions in both KH and tufted angioma can be strikingly similar, and in two of our patients, the diagnosis of tufted angioma was first entertained (1, 18). The “cannon ball” distribution of skin nodules, and their “tufting” into ectatic spaces were characteristic (1, 18). However, tumor nodules in KH coalesce, enlarge, and assume with the fibroblastic stroma a widely infiltrative pattern, a feature not observed in tufted angioma (1, 18). Nevertheless, the morphologic overlap between KH and tufted angioma has led to suggest that the two lesions belong to a same disease spectrum, and that tufted angioma may represent a minor form of KH (1, 7, 18). Although this is plausible, it is also clear that their distinction is important because of the different clinical and therapeutic implications (1, 17, 18). Therefore, when a cutaneous lesion is diagnosed as tufted angioma, it is fair to consider the possibility of KH, and to exclude it by clinical correlation, including the call for diagnostic imaging.

Although the retroperitoneal involvement in KH has been emphasized because of severe manifestations and death, only 18% of patients showed such distribution (4, 6, 15, 17). In fact, KH more commonly affects the trunk, limbs, and skin, with nearly 75% of cutaneous involvement (2, 5, 7, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17). Skin presentation is not only the most common, but also the most amenable to biopsy and diagnosis, irrespective of the tumor size. KH resemblance to many cutaneous vascular lesions is conducive to misdiagnosis, and requires a high index of suspicion. This series of five patients with cutaneous KH illustrates its marked diversity in clinical manifestation, anatomical distribution, extent, and unpredictable course, all of which contribute to its poor recognition and also to the difficulty in managing the patients. The extreme contrast between skin and deep soft tissue involvement is pictured in Patient 1, where skin lesions represent only the “tip of the iceberg.” An extremely protracted course is illustrated in Patient 4, who presumably has harbored a deep-seated tumor, which was “thriving underground,” causing repeated bone fractures and dissolution of bone grafts through decades before emerging on the skin surface. In Patient 5, the management was based on supportive therapy of what was regarded as a massive congenital “port wine” type hemangioma, and thus use of interferon for Kasabach-Merritt syndrome or of reconstructive surgery for limb function. Were it not for rehabilitation and amputation of a nonfunctional limb, the diagnosis of KH would not have been established from the detection of several typical tumor nodules. There is no questioned that interferon induced a partial clinical response with resolution of coagulopathy, but the role of traditional herbal medicine cannot be ascertained.

CONCLUSION

All five patients are in good general health, even though in three patients the bulk of the tumor has not been surgically removed. The mean follow-up of 19 years, and ranging between 8 and 35 years is sufficiently long to conclude that KH is not capable of metastasis (2, 14, 16, 17). Our Patient 1 appears to be the only one in the literature with involvement of regional lymph nodes, but it is arguable whether this represented a metastasis or a local extension of the tumor (11, 17). The persistence of tumor for decades in Patient 4 also suggests that KH has no tendency for spontaneous regression. In contrast, this series and other reported examples clearly indicate that the natural history of KH can be modified by interventions such as radiation, interferon, and possibly chemotherapy (11, 15, 16, 17). Both Patients 3 and 5 experienced partial regression with in situ reduction of tumor size following interferon, with no new flare-up observed clinically. On subsequent amputation, Patient 5 demonstrated very little residual tumor, and instead showed changes similar to regressed lesion of tufted angioma (18). This observation may further relate tufted angioma to KH, and biologically place KH toward the benign end of vascular tumors (7, 9, 14). Thus, the designation of hemangioendothelioma infers to its local aggressive behavior, but no longer for a metastatic potential. Although retroperitoneal disease has been regarded biologically distinct because of its high mortality, prompt therapeutic interventions have prevented this type of fatality, and such a distinction is not justified (4, 7, 15). One can also argue whether an early intervention with interferon for example, may prevent complications such as the Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, or the local aggressive infiltration of this tumor. However, interferon-alpha has been associated with neurologic complications such as spastic paraplegia, and caution should be exercised not to use it as a first line treatment (19). It appears thus critical that organ imaging and biopsy of even deep-seated tumors be performed to establish an early diagnosis, and match therapy with this potentially aggressive tumor.

References

Allen PW . Three new vascular tumors—Tufted angioma, Kaposiform infantile hemangioendothelioma, and proliferative cutaneous angiomatosis. Int J Surg Pathol 1994; 2: 63–72.

Beaubien ER, Ball NJ, Storwick GS . Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma: a locally aggressive vascular tumor. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998; 38: 799–802.

Blei F, Karp N, Rofsky N, Rosen R, Greco MA . Successful multimodal therapy for kaposiform hemangioendothelioma complicated by Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1998; 15: 295–305.

Botash RJ, Oliphant M, Capaldo G . Imaging of congenital Kaposiform retroperitoneal hemangioendothelioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. Clin Imaging 1996; 20: 17–20.

Deb G, Jenkner A, De Sio L, Boldrini R, Bosman C, Standoli N, et al. Spindle cell (Kaposiform) hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome in an infant: successful treatment with alpha-2A interferon. Med Pediatr Oncol 1997; 28: 358–361.

Ekfors TO, Kujari H, Herva R . Kaposi-like infantile hemangioendothelioma. Am J Surg Pathol 1993; 17: 314–316.

Enjolras O, Wassef M, Mazoyer E, Frieden IJ, Rieu PN, Drouet L, et al. Infants with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome do not have “true” hemangiomas. J Pediatr 1997; 130: 631–640.

Fukunaga M, Ushigome S, Ishikawa E . Kaposiform haemangioendothelioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. Histopathology 1996; 28: 281–284.

Garzon MC, Enjolras O, Frieden IJ . Vascular tumors and vascular malformations: evidence for an association. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42: 275–279.

Gianotti R, Gelmetti C, Alessi E . Congenital cutaneous multifocal kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. Am J Dermatopathol 1999; 21: 557–561.

Mac-Moune Lai F, Allen PW, Yuen PM, Leung PC . Locally metastasizing vascular tumor: spindle cell, epithelioid, or unclassified hemangioendothelioma? Am J Clin Pathol 1991; 96: 660–663.

McPartlin DW, Ghufoor K, Patel SK, Jayaraj S . A rare case of cutaneous kaposiform haemangioendothelioma. Int J Clin Pract 1999; 53: 562–563.

Mentzel T, Mazzoleni G, Dei Tos AP, Fletcher CDM . Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma in adults. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of three cases. Am J Clin Pathol 1997; 108: 450–455.

Neidt GW, Greco MA, Wierczorek R, Blanc WA, Knowles DM . Hemangioma with Kaposi’s sarcoma-like features: report of two cases. Pediatr Pathol 1989; 9: 567–575.

Sarkar M, Mulliken JB, Kozakewich HP, Robertson RL, Burrows PE . Thrombocytopenic coagulopathy (Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon) is associated with Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and not with common infantile hemangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997; 100: 1377–1386.

Vin-Christian K, McCalmont TH, Frieden IJ . Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma. An aggressive, locally invasive vascular tumor that can mimic hemangioma of infancy. Arch Dermatol 1997; 133: 1573–1578.

Zukerberg LR, Nickoloff BJ, Weiss SW . Kaposiform he-mangioendothelioma of infancy and childhood: an aggressive neoplasm associated with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome and lymphangiomatosis. Am J Surg Pathol 1993; 17: 321–328.

Lam WY, Mac-Moune Lai F, Look CN, Choi PCL, Allen PW . Tufted angioma with complete regression. J Cutan Pathol 1994; 21: 461–466.

Grimal I, Duveau E, Enjolras O, Verret JL, Cginies JL . Effectiveness and dangers of interferon-alpha in the treatment of severe hemangiomas in infants. Arch Pediatr 2000; 7: 163–167.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mac-Moune Lai, F., To, K., Choi, P. et al. Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma: Five Patients with Cutaneous Lesion and Long Follow-Up. Mod Pathol 14, 1087–1092 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880441

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880441

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Gutartige Hauttumoren bei Kindern

Der Hautarzt (2022)

-

Vascular Anomalies of the Head and Neck: A Pediatric Overview

Head and Neck Pathology (2021)

-

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with adolescent thoracic scoliosis: a case report and review of literature

European Spine Journal (2011)

-

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma of the Spleen in an Adult: An Initial Case Report

Pathology & Oncology Research (2011)

-

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma arising in the deltoid muscle without the Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon

Skeletal Radiology (2010)