Abstract

Oncolytic measles virus strains have activity against multiple tumor types and are currently in phase I clinical testing. Induction of the heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) constitutes one of the earliest changes in cellular gene expression following infection with RNA viruses including measles virus, and HSP70 upregulation induced by heat shock has been shown to result in increased measles virus cytotoxicity. HSP90 inhibitors such as geldanamycin (GA) or 17-allylaminogeldanamycin result in pharmacologic upregulation of HSP70 and they are currently in clinical testing as cancer therapeutics. We therefore investigated the hypothesis that heat shock protein inhibitors could augment the measles virus-induced cytopathic effect. We tested the combination of a measles virus derivative expressing soluble human carcinoembryonic antigen (MV-CEA) and GA in MDA-MB-231 (breast), SKOV3.IP (ovarian) and TE671 (rhabdomyosarcoma) cancer cell lines. Optimal synergy was accomplished when GA treatment was initiated 6–24 h following MV infection. Western immunoblotting confirmed HSP70 upregulation in combination-treated cells. Combination treatment resulted in statistically significant increase in syncytia formation as compared to MV-CEA infection alone. Clonogenic assays demonstrated significant decrease in tumor colony formation in MV-CEA/GA combination-treated cells. In addition there was increase in apoptosis by 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining. Western immunoblotting for caspase-9, caspase-8, caspase-3 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) demonstrated increase in cleaved caspase-8 and PARP. The pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK and caspase-8 inhibitor Z-IETD-FMK, but not the caspase-9 inhibitor Z-IEHD-FMK, protected tumor cells from MV-CEA/GA-induced PARP activation, indicating that apoptosis in combination-treated cells occurs mainly via the extrinsic caspase pathway. Treatment of normal cells, such as normal human fibroblasts, however, with the MV-CEA/GA combination, did not result in cytopathic effect, indicating that GA did not alter the MV-CEA specificity for tumor cells. One-step viral growth curves, western immunoblotting for MV-N protein expression, QRT-PCR quantitation of MV-genome copy number and CEA levels showed comparable proliferation of MV-CEA in GA-treated vs -untreated tumor cells. Rho activation assays and western blot for total RhoA, a GTPase associated with the actin cytoskeleton, demonstrated decrease in RhoA activation in combination-treated cells, a change previously shown to be associated with increase in paramyxovirus-induced cell–cell fusion. The enhanced cytopathic effect resulting from measles virus/GA combination supports the translational potential of this approach in the treatment of cancer.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wild TF, Malvoisin E, Buckland R . Measles virus: both the haemagglutinin and fusion glycoproteins are required for fusion. J Gen Virol 1991; 72 (Part 2): 439–442.

Grote D, Russell SJ, Cornu TI, Cattaneo R, Vile R, Poland GA et al. Live attenuated measles virus induces regression of human lymphoma xenografts in immunodeficient mice. Blood 2001; 97: 3746–3754.

Peng KW, Ahmann GJ, Pham L, Greipp PR, Cattaneo R, Russell SJ . Systemic therapy of myeloma xenografts by an attenuated measles virus. Blood 2001; 98: 2002–2007.

Peng KW, TenEyck CJ, Galanis E, Kalli KR, Hartmann LC, Russell SJ . Intraperitoneal therapy of ovarian cancer using an engineered measles virus. Cancer Res 2002; 62: 4656–4662.

Blechacz B, Splinter PL, Greiner S, Myers R, Peng KW, Federspiel MJ et al. Engineered measles virus as a novel oncolytic viral therapy system for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2006; 44: 1465–1477.

Phuong LK, Allen C, Peng KW, Giannini C, Greiner S, TenEyck CJ et al. Use of a vaccine strain of measles virus genetically engineered to produce carcinoembryonic antigen as a novel therapeutic agent against glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 2462–2469.

McDonald CJ, Erlichman C, Ingle JN, Rosales GA, Allen C, Greiner SM et al. A measles virus vaccine strain derivative as a novel oncolytic agent against breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2006; 99: 177–184.

Oglesbee MJ, Pratt M, Carsillo T . Role for heat shock proteins in the immune response to measles virus infection. Viral Immunol 2002; 15: 399–416.

Parks CL, Lerch RA, Walpita P, Sidhu MS, Udem SA . Enhanced measles virus cDNA rescue and gene expression after heat shock. J Virol 1999; 73: 3560–3566.

Vasconcelos DY, Cai XH, Oglesbee MJ . Constitutive overexpression of the major inducible 70 kDa heat shock protein mediates large plaque formation by measles virus. J Gen Virol 1998; 79 (Part 9): 2239–2247.

Vasconcelos D, Norrby E, Oglesbee M . The cellular stress response increases measles virus-induced cytopathic effect. J Gen Virol 1998; 79 (Part 7): 1769–1773.

Whitesell L, Bagatell R, Falsey R . The stress response: implications for the clinical development of hsp90 inhibitors. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2003; 3: 349–358.

Maloney A, Clarke PA, Workman P . Genes and proteins governing the cellular sensitivity to HSP90 inhibitors: a mechanistic perspective. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2003; 3: 331–341.

Scheibel T, Siegmund HI, Jaenicke R, Ganz P, Lilie H, Buchner J . The charged region of Hsp90 modulates the function of the N-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999; 96: 1297–1302.

Goetz MP, Toft DO, Ames MM, Erlichman C . The Hsp90 chaperone complex as a novel target for cancer therapy. Ann Oncol 2003; 14: 1169–1176.

Price JT, Quinn JM, Sims NA, Vieusseux J, Waldeck K, Docherty SE et al. The heat shock protein 90 inhibitor, 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin, enhances osteoclast formation and potentiates bone metastasis of a human breast cancer cell line. Cancer Res 2005; 65: 4929–4938.

Burger AM, Fiebig HH, Stinson SF, Sausville EA . 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin activity in human melanoma models. Anticancer Drugs 2004; 15: 377–387.

Banerji U, Walton M, Raynaud F, Grimshaw R, Kelland L, Valenti M et al. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for the heat shock protein 90 molecular chaperone inhibitor 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin in human ovarian cancer xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 7023–7032.

Goetz MP, Toft D, Reid J, Ames M, Stensgard B, Safgren S et al. Phase I trial of 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1078–1087.

Nowakowski GS, McCollum AK, Ames MM, Mandrekar SJ, Reid JM, Adjei AA et al. A phase I trial of twice-weekly 17-allylamino-demethoxy-geldanamycin in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 6087–6093.

Park SH, Bolender N, Eisele F, Kostova Z, Takeuchi J, Coffino P et al. The cytoplasmic Hsp70 chaperone machinery subjects misfolded and endoplasmic reticulum import-incompetent proteins to degradation via the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Mol Biol Cell 2007; 18: 153–165.

Mayer MP, Bukau B . Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci 2005; 62: 670–684.

Bukau B . Ribosomes catch Hsp70s. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2005; 12: 472–473.

Hartl FU . Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature 1996; 381: 571–579.

Schowalter RM, Wurth MA, Aguilar HC, Lee B, Moncman CL, McCann RO et al. Rho GTPase activity modulates paramyxovirus fusion protein-mediated cell–cell fusion. Virology 2006; 350: 323–334.

Pai KS, Mahajan VB, Lau A, Cunningham DD . Thrombin receptor signaling to cytoskeleton requires Hsp90. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 32642–32647.

Whitesell L, Shifrin SD, Schwab G, Neckers LM . Benzoquinonoid ansamycins possess selective tumoricidal activity unrelated to src kinase inhibition. Cancer Res 1992; 52: 1721–1728.

Schnur RC, Corman ML, Gallaschun RJ, Cooper BA, Dee MF, Doty JL et al. erbB-2 oncogene inhibition by geldanamycin derivatives: synthesis, mechanism of action, and structure-activity relationships. J Med Chem 1995; 38: 3813–3820.

Grenert JP, Sullivan WP, Fadden P, Haystead TA, Clark J, Mimnaugh E et al. The amino-terminal domain of heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) that binds geldanamycin is an ATP/ADP switch domain that regulates hsp90 conformation. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 23843–23850.

Prodromou C, Roe SM, O'Brien R, Ladbury JE, Piper PW, Pearl LH . Identification and structural characterization of the ATP/ADP-binding site in the Hsp90 molecular chaperone. Cell 1997; 90: 65–75.

Stebbins CE, Russo AA, Schneider C, Rosen N, Hartl FU, Pavletich NP . Crystal structure of an Hsp90-geldanamycin complex: targeting of a protein chaperone by an antitumor agent. Cell 1997; 89: 239–250.

An WG, Schnur RC, Neckers L, Blagosklonny MV . Depletion of p185erbB2, Raf-1 and mutant p53 proteins by geldanamycin derivatives correlates with antiproliferative activity. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1997; 40: 60–64.

Obermann WM, Sondermann H, Russo AA, Pavletich NP, Hartl FU . In vivo function of Hsp90 is dependent on ATP binding and ATP hydrolysis. J Cell Biol 1998; 143: 901–910.

Solit DB, Zheng FF, Drobnjak M, Munster PN, Higgins B, Verbel D et al. 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin induces the degradation of androgen receptor and HER-2/neu and inhibits the growth of prostate cancer xenografts. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 986–993.

Kelland LR, Sharp SY, Rogers PM, Myers TG, Workman P . DT-diaphorase expression and tumor cell sensitivity to 17-allylamino, 17-demethoxygeldanamycin, an inhibitor of heat shock protein 90. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 1940–1949.

Whitesell L, Sutphin PD, Pulcini EJ, Martinez JD, Cook PH . The physical association of multiple molecular chaperone proteins with mutant p53 is altered by geldanamycin, an hsp90-binding agent. Mol Cell Biol 1998; 18: 1517–1524.

Anderson BD, Nakamura T, Russell SJ, Peng KW . High CD46 receptor density determines preferential killing of tumor cells by oncolytic measles virus. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 4919–4926.

Rahmani M, Yu C, Dai Y, Reese E, Ahmed W, Dent P et al. Coadministration of the heat shock protein 90 antagonist 17-allylamino- 17-demethoxygeldanamycin with suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid or sodium butyrate synergistically induces apoptosis in human leukemia cells. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 8420–8427.

Liu C, Sarkaria J, Allen C, Zollman PJ, James CD, Russell SJ et al. Combination of oncolytic measles virus strains and radiation therapy has synergisitic activity in the treatment of glioblastoma multiforme. (Abstract 44). Mol Ther 2006; 13 (suppl 1): s19.

Sylwester A, Wessels D, Anderson SA, Warren RQ, Shutt DC, Kennedy RC et al. HIV-induced syncytia of a T cell line form single giant pseudopods and are motile. J Cell Sci 1993; 106 (Part 3): 941–953.

Eitzen G . Actin remodeling to facilitate membrane fusion. Biochim Biophys Acta 2003; 1641: 175–181.

Singh I, Knezevic N, Ahmmed GU, Kini V, Malik AB, Mehta D . G{alpha}q-TRPC6-mediated Ca2+ Entry Induces RhoA Activation and Resultant Endothelial Cell Shape Change in Response to Thrombin. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 7833–7843.

Goldberg L, Kloog Y . A Ras inhibitor tilts the balance between Rac and Rho and blocks phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent glioblastoma cell migration. Cancer Res 2006; 66: 11709–11717.

Rittinger K, Walker PA, Eccleston JF, Smerdon SJ, Gamblin SJ . Structure at 1.65 A of RhoA and its GTPase-activating protein in complex with a transition-state analogue. Nature 1997; 389: 758–762.

Gower TL, Pastey MK, Peeples ME, Collins PL, McCurdy LH, Hart TK et al. RhoA signaling is required for respiratory syncytial virus-induced syncytium formation and filamentous virion morphology. J Virol 2005; 79: 5326–5336.

Liu TS, Musch MW, Sugi K, Walsh-Reitz MM, Ropeleski MJ, Hendrickson BA et al. Protective role of HSP72 against Clostridium difficile toxin A-induced intestinal epithelial cell dysfunction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003; 284: C1073–C1082.

Sastry SK, Rajfur Z, Liu BP, Cote JF, Tremblay ML, Burridge K . PTP-PEST couples membrane protrusion and tail retraction via VAV2 and p190RhoGAP. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 11627–11636.

Carsillo T, Traylor Z, Choi C, Niewiesk S, Oglesbee M . hsp72, a host determinant of measles virus neurovirulence. J Virol 2006; 80: 11031–11039.

Okamoto T, Nishimura Y, Ichimura T, Suzuki K, Miyamura T, Suzuki T et al. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by FKBP8 and Hsp90. EMBO J 2006; 25: 5015–5025.

Connor JH, McKenzie MO, Parks GD, Lyles DS . Antiviral activity and RNA polymerase degradation following Hsp90 inhibition in a range of negative strand viruses. Virology 2007; 362: 109–119.

Dressel R, Grzeszik C, Kreiss M, Lindemann D, Herrmann T, Walter L et al. Differential effect of acute and permanent heat shock protein 70 overexpression in tumor cells on lysability by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 8212–8220.

Asea A, Kraeft SK, Kurt-Jones EA, Stevenson MA, Chen LB, Finberg RW et al. HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat Med 2000; 6: 435–442.

Peng KW, Facteau S, Wegman T, O′Kane D, Russell SJ . Non-invasive in vivo monitoring of trackable viruses expressing soluble marker peptides. Nat Med 2002; 8: 527–531.

Fulda S, Scaffidi C, Pietsch T, Krammer PH, Peter ME, Debatin KM . Activation of the CD95 (APO-1/Fas) pathway in drug- and gamma-irradiation-induced apoptosis of brain tumor cells. Cell Death Differ 1998; 5: 884–893.

Nakamura T, Peng KW, Vongpunsawad S, Harvey M, Mizuguchi H, Hayakawa T et al. Antibody-targeted cell fusion. Nat Biotechnol 2004; 22: 331–336.

Liu C, Musch MW, Sugi K, Walsh-Reitz MM, Ropeleski MJ, Hendrickson BA et al. Proapoptotic, antimigratory, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic effects of commercial C-reactive protein on various human endothelial cell types in vitro: implications of contaminating presence of sodium azide in commercial preparation. Circ Res 2005; 97: 135–143.

Ren XD, Kiosses WB, Schwartz MA . Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J 1999; 18: 578–585.

Servotte S, Zhang Z, Lambert CA, Ho TT, Chometon G, Eckes B et al. Establishment of stable human fibroblast cell lines constitutively expressing active Rho-GTPases. Protoplasma 2006; 229: 215–220.

Qiu RG, Chen J, McCormick F, Symons M . A role for Rho in Ras transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 11781–11785.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Atwater Fund (EG); P50 CA 116201 (JNI, EG); P50 CA 108961 (EG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

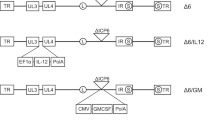

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Gene Therapy website (http://www.nature.com/gt)

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, C., Erlichman, C., McDonald, C. et al. Heat shock protein inhibitors increase the efficacy of measles virotherapy. Gene Ther 15, 1024–1034 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/gt.2008.30

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gt.2008.30

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

An armed oncolytic measles vaccine virus eliminates human hepatoma cells independently of apoptosis

Gene Therapy (2013)

-

Intelligent Design: Combination Therapy With Oncolytic Viruses

Molecular Therapy (2010)

-

Therapeutic Potential of Oncolytic Measles Virus: Promises and Challenges

Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics (2010)