Abstract

One of the possible therapies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is the introduction of a functional copy of the dystrophin gene into the patient. For this approach to be effective, therapeutic levels and long-term expression of the protein need to be achieved. However, immune responses to the newly expressed dystrophin have been predicted, particularly in DMD patients who express no dystrophin or only very truncated versions. In a previous study, we demonstrated a strong humoral and cytotoxic immune response to human dystrophin in the mdx mouse. However, the mdx mouse was tolerant to murine dystrophin, possibly due to the endogenous expression of dystrophin in revertant fibres or the other nonmuscle dystrophin isoforms. In the present study, we delivered human and murine dystrophin plasmids by electrotransfer after hyaluronidase pretreatment to increase gene transfer efficiencies. Tolerance to murine dystrophin was still seen with this improved gene delivery. Tolerance to exogenous recombinant full-length human dystrophin was seen in mdx transgenic lines expressing internally deleted versions of human dystrophin. These results suggest that the presence of revertant fibres may prevent the development of serious immune responses in patients undergoing dystrophin gene therapy.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Emery A . Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1993.

Monaco AP et al. An explanation for the phenotypic differences between patients bearing partial deletions of the DMD locus. Genomics 1988; 2: 90–95.

Winder SJ . The membrane–cytoskeleton interface: the role of dystrophin and utrophin. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 1997; 18: 617–629.

Sicinski P et al. The molecular basis of muscular dystrophy in the mdx mouse: a point mutation. Science 1989; 244: 1578–1580.

Hoffman EP, Morgan JE, Watkins SC, Partridge TA . Somatic reversion/suppression of the mouse mdx phenotype in vivo. J Neurol Sci 1990; 99: 9–25.

Lu QL et al. Massive idiosyncratic exon skipping corrects the nonsense mutation in dystrophic mouse muscle and produces functional revertant fibers by clonal expansion. J Cell Biol 2000; 148: 985–996.

Barton-Davis ER et al. Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore dystrophin function to skeletal muscles of mdx mice. J Clin Invest 1999; 104: 375–381.

Bartlett RJ et al. In vivo targeted repair of a point mutation in the canine dystrophin gene by a chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotide. Nat Biotechnol 2000; 18: 615–622.

Rando TA, Disatnik MH, Zhou LZ . Rescue of dystrophin expression in mdx mouse muscle by RNA/DNA oligonucleotides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 5363–5368.

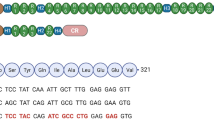

Mann CJ et al. Antisense-induced exon skipping and synthesis of dystrophin in the mdx mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98: 42–47.

Lu QL et al. Functional amounts of dystrophin produced by skipping the mutated exon in the mdx dystrophic mouse. Nat Med 2003; 9: 1009–1014.

Partridge TA et al. Conversion of mdx myofibres from dystrophin-negative to -positive by injection of normal myoblasts. Nature 1989; 337: 176–179.

Skuk D, Goulet M, Roy B, Tremblay JP . Efficacy of myoblast transplantation in nonhuman primates following simple intramuscular cell injections: toward defining strategies applicable to humans. Exp Neurol 2002; 175: 112–126.

Bujold M et al. Autotransplantation in mdx mice of mdx myoblasts genetically corrected by an HSV-1 amplicon vector. Cell Transplant 2002; 11: 759–767.

Wang B, Li J, Xiao X . Adeno-associated virus vector carrying human minidystrophin genes effectively ameliorates muscular dystrophy in mdx mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 13714–13719.

DelloRusso C et al. Functional correction of adult mdx mouse muscle using gutted adenoviral vectors expressing full-length dystrophin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 12979–12984.

Gilbert R et al. Prolonged dystrophin expression and functional correction of mdx mouse muscle following gene transfer with a helper-dependent (gutted) adenovirus-encoding murine dystrophin. Hum Mol Genet 2003; 12: 1287–1299.

Ferrer A, Wells KE, Wells DJ . Immune responses to dystrophin: implications for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Gene Therapy 2000; 7: 1439–1446.

Braun S et al. Immune rejection of human dystrophin following intramuscular injections of naked DNA in mdx mice. Gene Therapy 2000; 7: 1447–1457.

Gollins H, McMahon J, Wells KE, Wells DJ . High-efficiency plasmid gene transfer into dystrophic muscle. Gene Therapy 2003; 10: 504–512.

Tinsley JM, Davies KE . Utrophin: a potential replacement for dystrophin? Neuromuscul Disord 1993; 3: 537–539.

Karpati G et al. Myoblast transfer in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol 1993; 34: 8–17.

Acsadi G et al. Dystrophin expression in muscles of mdx mice after adenovirus-mediated in vivo gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther 1996; 7: 129–140.

Lochmuller H et al. Transient immunosuppression by FK506 permits a sustained high-level dystrophin expression after adenovirus-mediated dystrophin minigene transfer to skeletal muscles of adult dystrophic (mdx) mice. Gene Therapy 1996; 3: 706–716.

McMahon JM et al. Optimisation of electrotransfer of plasmid into skeletal muscle by pretreatment with hyaluronidase – increased expression with reduced muscle damage. Gene Therapy 2001; 8: 1264–1270.

Cox GA, Phelps SF, Chapman VM, Chamberlain JS . New mdx mutation disrupts expression of muscle and nonmuscle isoforms of dystrophin. Nat Genet 1993; 4: 87–93.

Wells DJ et al. Expression of human full-length and minidystrophin in transgenic mdx mice: implications for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet 1995; 4: 1245–1250.

Wells KE et al. Enhanced in vivo delivery of antisense oligonucleotides to restore dystrophin expression in adult mdx mouse muscle. FEBS Lett 2003; 552: 145–149.

Phelps SF et al. Expression of full-length and truncated dystrophin mini-genes in transgenic mdx mice. Hum Mol Genet 1995; 4: 1251–1258.

Chao DS et al. Selective loss of sarcolemmal nitric oxide synthase in Becker muscular dystrophy. J Exp Med 1996; 184: 609–618.

Wells KE et al. Relocalization of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) as a marker for complete restoration of the dystrophin associated protein complex in skeletal muscle. Neuromuscul Disord 2003; 13: 21–31.

Danko I et al. Dystrophin expression improves myofiber survival in mdx muscle following intramuscular plasmid DNA injection. Hum Mol Genet 1993; 2: 2055–2061.

Acsadi G et al. Human dystrophin expression in mdx mice after intramuscular injection of DNA constructs. Nature 1991; 352: 815–818.

Vilquin JT et al. Electrotransfer of naked DNA in the skeletal muscles of animal models of muscular dystrophies. Gene Therapy 2001; 8: 1097–1107.

Murakami T et al. Full-length dystrophin cDNA transfer into skeletal muscle of adult mdx mice by electroporation. Muscle Nerve 2003; 27: 237–241.

Weeratna RD et al. Designing gene therapy vectors: avoiding immune responses by using tissue-specific promoters. Gene Therapy 2001; 8: 1872–1878.

Corr M, von Damm A, Lee DJ, Tighe H . In vivo priming by DNA injection occurs predominantly by antigen transfer. J Immunol 1999; 163: 4721–4727.

Ohtsuka Y et al. Dystrophin acts as a transplantation rejection antigen in dystrophin- deficient mice: implication for gene therapy. J Immunol 1998; 160: 4635–4640.

Gilchrist SC, Ontell MP, Kochanek S, Clemens PR . Immune response to full-length dystrophin delivered to Dmd muscle by a high-capacity adenoviral vector. Mol Ther 2002; 6: 359–368.

Voit T, Stuettgen P, Cremer M, Goebel HH . Dystrophin as a diagnostic marker in Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Correlation of immunofluorescence and western blot. Neuropediatrics 1991; 22: 152–162.

Burrow KL et al. Dystrophin expression and somatic reversion in prednisone-treated and untreated Duchenne dystrophy. CIDD Study Group. Neurology 1991; 41: 661–666.

Klein CJ et al. Somatic reversion/suppression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD): evidence supporting a frame-restoring mechanism in rare dystrophin-positive fibers. Am J Hum Genet 1992; 50: 950–959.

Uchino M et al. PCR and immunocytochemical analyses of dystrophin-positive fibers in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol Sci 1995; 129: 44–50.

Ginhoux F et al. Identification of an HLA-A*0201-restricted epitopic peptide from human dystrophin: application in Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene therapy. Mol Ther 2003; 8: 274–283.

Romero NB et al. Current protocol of a research phase I clinical trial of full-length dystrophin plasmid DNA in Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophies. Part II: clinical protocol. Neuromuscul Disord 2002; 12 (Suppl 1): S45–S48.

Roberts RG, Gardner RJ, Bobrow M . Searching for the 1 in 2,400,000: a review of dystrophin gene point mutations. Hum Mutat 1994; 4: 1–11.

Wells KE . Optimisation of constructs for gene therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PhD Thesis, University of London, 2000.

Caldwell CJ, Mattey DL, Weller RO . Role of the basement membrane in the regeneration of skeletal muscle. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 1990; 16: 225–238.

Wells DJ . Improved gene transfer by direct plasmid injection associated with regeneration in mouse skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett 1993; 332: 179–182.

Spencer MJ, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Dorshkind K, Tidball JG . Helper (CD4(+)) and cytotoxic (CD8(+)) T cells promote the pathology of dystrophin-deficient muscle. Clin Immunol 2001; 98: 235–243.

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by grants from the Muscular Dystrophy Campaign of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Muscular Dystrophy Association of America, the Association Francaise contre les Myopathies and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrer, A., Foster, H., Wells, K. et al. Long-term expression of full-length human dystrophin in transgenic mdx mice expressing internally deleted human dystrophins. Gene Ther 11, 884–893 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3302242

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3302242

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Molecular-Targeted Therapy for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy (2008)

-

Multiplicity of experimental approaches to therapy for genetic muscle diseases and necessity for population screening

Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility (2008)

-

Gene therapy progress and prospects: Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Gene Therapy (2006)

-

Therapeutic restoration of dystrophin expression in Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility (2006)

-

DNA electrotransfer: its principles and an updated review of its therapeutic applications

Gene Therapy (2004)