Abstract

Design

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in a university's oral and maxillofacial unit.

Intervention

Patients who had dentofacial deformities but who had completed their presurgical orthodontic treatment were randomly assigned into the titanium and resorbable fixation groups.

Outcome measure

Intraoperative data, such as the surgical procedures, time for fixing each plate, and number of broken plates and screws, were recorded. Participants were followed up at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively. Subjective and objective parameters related to clinical morbidities were assessed.

Results

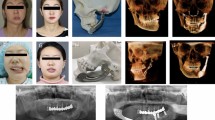

A total of 60 patients with 177 osteotomies were included in this study. Eighty-seven osteotomies fixed with 196 titanium plates and 784 titanium screws were performed in 30 individuals, whereas 90 osteotomies were fixed with 165 resorbable plates and 658 resorbable screws in a second group of 30 participants. The postoperative infection rate was 1.53% (three out of 196) and 1.82% (three out of 165) in the titanium and resorbable fixation groups, respectively. These infections were mainly due to loose screws and wound dehiscence. The plate exposure rate was 1.02% (two out of 196) for the titanium group and 1.21% (two out of 165) for the resorbable group. The plate removal rate in the titanium and resorbable groups was 1.53% (three out of 196) and 3.63% (six out of 165), respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the plating time of step (mandibular body) and Hofer (mandibular subapical) osteotomies. There was no significant difference in the subjective clinical parameters such as wound discomfort, clinical stability of the osteotomy segments, palpability of plate and overall satisfaction with the result between the two fixation groups. Similarly, objective parameters, including wound dehiscence, rate of infection, plate exposure, occurrence of sinus tract and palpability assessed by surgeons, showed no significant difference between the groups.

Conclusions

Bioresorbable fixation devices are functionally equivalent to titanium for fixation in orthognathic surgery and do not increase clinical morbidities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Clinical morbidity following use of resorbable osteofixation in orthognathic surgery was compared with titanium osteofixation in an RCT, in respect of infection rates, plate exposure, operation time, postoperative wound discomfort, segment stability, plate palpability and patient satisfaction. This was performed in an Asian population of typical deformity, age, sex and smoking distribution. Full patient randomisation within a controlled time period is the main advantage of this study. This has become difficult today because, at least in Europe, informed patients demand resorbables and full preoperative information as to the type of fixation that will be used in their case.

First, with regard to handling, the resorbable fixatation required a significantly longer plating time, although this levelled out with experience. Screw breakage (reported in 5% of uses) is a frequent problem when a surgeon accustomed to titanium osteofixation attempts to use similar insertion torque with resorbable screws. Increasing experience of the surgeon decreases the rate of intraoperative osteofixation failure, with the reduction in screw breakage even reported to be significant over time.

Plate fracture (seen in 2% of plates) repeatedly occurs when complicated shapes, such as in a Le-Fort I advancement , need to be adapted. Cold bending of self-reinforced plates may be more likely to cause plate fracture than plate bending after molecular activation within a heating saline basin, as performed with alternative plates.1, 2, 3 Mandibular plating was performed in a wide range of osteotomies with different local postoperative loadings. Postoperative plate fractures occur when osteofixation is too weak for retention of bone segments, as occurred in one of our studies.2

In my opinion, the follow-up included too many radiographs, the authors stating that a set of radiographs (a minimum of two?) was taken at each follow-up visit, at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 and 6 months, and 1 and 2 years, equalling 12 postoperative radiographies per patient.

Looking at biocompatibility, literature estimates of symptomatic titanium plate removal vary slightly, around the 10% level. Similar complication rates in the control group are reported by the authors here: the rate is lower when given per single osteofixation, but equals 10% if given per patient. In terms of infection, I am surprised by the infection rates in the study: our experience with similar osteofixation (non-self-reinforced poly70L-lactide-co-30DL-lactide [P(L/DL)LA] resorbable plates) resulted in no cases of acute infection. In my experience, in fact, an advantage of resorbable osteofixation is that these plates do not seem to increase the likelihood of acute infection of the soft tissues as occurs with titanium osteofixation. Only slight granulocytic infiltration occurs when sterile fistulation to the oral cavity permits local contamination with oral flora.2, 3 Fistulae, pain, discharge and osteolyses, according to our immunohistological workup, came from foreign-body reactions triggered by material crystallinity. This could likewise have been stimulated by self-reinforcement of the plates used in the present study. The occurrence of a late infection (6 weeks–6 months postoperatively, as in the sinus development) is another indication of foreign body reaction: it seems likely to me that infections in the study group here should be considered medium–severe foreign body reactions.

It would be interesting to re-evaluate the palpability of the plates today, after 3 more years, ie, whether, after 5 years in total, the self-reinforced plates are still palpable in any patient except the 10% given at the end of the 2-year follow-up. Direct postoperative minor segment instability up to 6 weeks is regularly reported in the literature. We have also initially judged ‘clinical’ stability,2 although a more differentiated workup of segment stability according to direction and extent of segmental movement is prospectively needed and anticipated as a future project.3 For this evaluation it is important to separate cleft-lip and palate-associated and syndromic dysgnathia from nonsyndromic dentofacial deformities, because the previous operations and their resulting scars have considerable influence upon segmental stability. The type of resorbable osteofixation requires separate attention because, for example, titanium microplates do not have identical retention capacity to midiplates, and the same goes for resorbable osteofixation. More and more manufacturers meanwhile construct osteofixations differentiated by indication, with tailored polymer composition and osteoconductive incorporation as hydroxyl-apatite.

The authors monitored patient satisfaction using a visual analogue scale. This information could have been refined, however, by using more specific questionnaires, especially to filter out subsequent lower pain levels in resorbable fixation, suggested by the authors without statistically significant data. In summary, however, the authors here have significantly contributed to our knowledge of resorbable osteofixation in orthognathic surgery with their fine work. Further research will include fixation-type-dependent evaluation of segment stability and biocompatibility assessment for new polymers, focusing upon in situ recrystallisation. Patient demand and satisfaction assessment will continue to make patient comfort an aim, perhaps fuelling future debate with health insurance providers. From a public health standpoint examination of the cost-effectiveness of advanced osteofixation technique is mandatory in the light of the benefits of avoiding metal plate removal.

Practice point

Resorbable osteofixation in orthognathic surgery reliably avoids implant removal, with comparable clinical morbidity to titanium fixation.

References

Landes CA, Ballon A, Roth C . In-patient versus in vitro degradation of P(L/DL)LA and PLGA. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2006; 76: 403–411.

Landes CA, Kriener S . Resorbable plate-osteosynthesis of sagittal split osteotomies with major bone movement. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2003; 111: 1828–1840.

Landes CA, Ballon A . Cleft lip and palate orthognathic surgery 5-year outcome, comparing resorbable miniplate to titanium osteosynthesis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2006; 43: 67–74.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Professor Lim K Cheung, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Prince Philip Dental Hospital, 34 Hospital Road, Hong Kong. E-mail: lkcheung@hkucc.hku.hk

Cheung LK, Chow LK, Chiu WK. A randomized controlled trial of resorbable versus titanium fixation for orthognathic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004; 98:386–397

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Landes, C. Bioresorbable fixation devices function similarly to titanium in fixation for orthognathic surgery. Evid Based Dent 7, 48–49 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400394

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400394