Abstract

Data sources

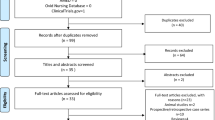

Medline, Cochrane, Web of Science, SciELO and Embase databases from 1993-2014.

Study selection

Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) comparing a manual therapy physical therapy intervention to a reference group (placebo intervention, controlled comparison intervention, standard treatment or other treatment).

Data extraction and synthesis

Two independent reviewers abstracted data and assessed quality and clinical relevance of each paper. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted. The PEDro (Physiotherapy Evidence-Based Database) scale was used to assess the methodological quality of the studies.

Results

Eight studies were included. The number of patients in the studies ranged from 30-93. Seven out of the eight studies presented high methodological quality. Treatment effect size was calculated for pain, maximum mouth opening (MMO) and pressure pain threshold (PPT). There was moderate and low evidence that myofascial release and massage techniques are more effective than placebo or no intervention for MMO and pain outcomes respectively. There was also moderate evidence that no significant difference exists between myofascial release and toxin botulinum for improvement on the same outcomes. There was low to high quality evidence that upper cervical spine thrust manipulation or mobilisation techniques are more effective than control, while thoracic manipulations are not. Overall there was moderate-to-high evidence that MT techniques protocols are effective. Methodological heterogeneity of the trial protocols frequently contributed to a decrease in the quality of evidence.

Conclusions

There is widely varying evidence that MT improves pain, MMO and PPT in subjects with TMD signs and symptoms, depending on the technique. Further studies should consider using standardised evaluations and better study designs to strengthen clinical relevance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

This appears to be a well-conducted systematic review. Its aim is to analyse the evidence regarding the isolated effect of Manual Therapy (MT) on improving signs and symptoms in TMD patients. Despite the overall high quality of the studies included, the heterogeneity of several aspects of them makes analysis difficult and meta-analysis impossible. Nevertheless, we can conclude that the clinical dentist may benefit from the assistance of a manual therapist in treating patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD).

Various factors point to this being an example of a good systematic review. First of all, the inclusion criteria stipulated that only randomised controlled trials studies should be included. Randomised controlled trials are the gold standard for testing treatments. Moreover, only studies where at least one of the intervention groups had exclusively received some modality of MT were included, thus allowing the assessment of MT independently of other treatments. Also, the outcome measures selected (maximum mouth opening and pressure pain threshold) are of a high clinical relevance because they represent the main complaints of subjects with TMD.

It is unfortunate that grey literature was not included in the review, as this may have provided more studies for analysis. In addition, Manual Therapy may be too broad a subject area for such a review. For instance, some studies evaluated thrust joint manipulation techniques whilst others evaluated massages of the masticatory muscles. These techniques come from disciplines as different as physiotherapy and osteopathy, and consequently they are not easily comparable. As a result of this difference, and of others inherent to the eight studies, a significant heterogeneity arises. Other factors contributing to this heterogeneity are: variation in the applied protocols regarding the number of sessions, the frequency of therapy application and the follow-up. In addition, and perhaps more concerning with respect to clinical practice, a variation in the method of diagnosis of TMD was detected among the studies. With regard to this variation, the authors suggest that the use of a standardised evaluation protocol, which has been available since 1992, could act as a point of reference for researchers, faculties and clinicians.

The heterogeneity mentioned above influenced the way in which the systematic review was conducted: the authors were initially obliged to divide the studies into groups according to the body structure that received MT. There was also an influence on the results in that the methodological heterogeneity across trials protocols frequently contributed to a decrease in the quality of evidence.

An interesting point to observe among the characteristics of subjects included in the primary studies is that females predominated (62.6%) and in one particular study the sample was composed exclusively of women. Given that presenting TMD signs and symptoms was an inclusion criteria, this may be another indication that women are more predisposed to suffer from TMD than men or, alternatively, that women report more this kind of problem than men. This difference between genders has been noted previously.1

Most of the studies in this review were high methodological quality studies and presented positive effects on pain and maximum mouth opening in response to MT techniques. Taking this finding and all of the previous analysis into account, we could conclude that because of the high frequency of TMD problems in general populations general dentists would benefit from the assistance of manual therapists who are familiar with TMD.

But why should MT be given priority over other therapies? Because, as no definitive treatment for TMD has yet been established, and in the absence of better evidence, it makes sense to begin with a non-invasive and reversible therapy rather than using irreversible techniques. Some schools of occlusion such as the one in Lille, France, have been including MT in their protocols to treat TMD for decades. Moreover, in Belgium, dentists have recently been allowed to prescribe physical therapy sessions only in cases of TMD.

In conclusion, it appears that this review intended to assess the isolated effect of manual therapies in treating temporomandibular disorders. Despite the fact that different techniques were included in what the review terms manual therapies, and despite the various other causes of heterogeneity among the studies, there appears to be evidence that manual therapies may alleviate patients suffering from temporomandibular disorders. However to improve the evaluation of treatments for TMD there is a need for standardised protocols for the diagnosis and reporting of TMD studies and for more studies to follow SPIRIT (http://www.spirit-statement.org/) and CONSORT (http://www.consort-statement.org/) guidelines.

Practice point

-

Working with a manual therapist who is familiar with TMD would appear to be a logical, conservative and evidence-based approach to the treatment of this very frequent cause of pain among patients.

References

LeResche L . Epidemiology of disorders: implications for the investigation of etiologic factors. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 1997; 8: 291–305.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Ana Beatriz Oliveira, Departamento de Fisioterapia, Universidade Federal de Sao Carlos, Via Washington Luis, KM 235, CP 676, CEP 13565-905 Sao Carlos, Brazil. E-mail: biaoliveira@ufscar.br; biaoliveira@gmail.com

Calixtre LB, Moreira RF, Franchini GH, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Oliveira AB. Manual therapy for the management of pain and limited range of motion in subjects with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. J Oral Rehabil 2015; 42: 847–861

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morell, G. Manual therapy improved signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. Evid Based Dent 17, 25–26 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401155

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401155