Abstract

Data sources

Eight electronic databases were searched: Medline (through PubMed), ISI Web of Science, Scopus, The Cochrane Library, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Lilacs and the Brazilian Library of Dentistry, Controlled-trials database of Clinical Trials and Clinical Trials-US National Institute of Health. A grey literature search was also conducted and reference lists of included studies were interrogated.

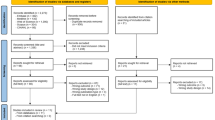

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were studies which examined the relationship between oral health literacy and one of the pre-defined outcomes including oral health behaviours, perception, knowledge and dental treatment outcomes. Epidemiological studies (such a case-control, cohort, cross-sectional and clinical trials) were included but qualitative studies, systematic reviews and those which examined unrelated outcomes were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two independent reviewers carried out screening, risk of bias assessment and data extraction for all studies against pre-agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (a modified version for cross-sectional studies) and the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool were used for quality appraisal. A narrative synthesis was presented, with meta-analysis of a small sub-group of studies relating to one outcome.

Results

Twenty-five studies were included in the final review; 21 cross-sectional, two cohort, one case-control and one clinical trial. Most (17) were considered to be at high risk of bias and there was a high degree of clinical and methodological heterogeneity. No evidence was found of a significant association between oral health literacy and the outcomes considered.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that the current scientific evidence suggests that no association exists between oral health literacy and any of the outcomes investigated. Further prospective studies with high methodological quality are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

NHS Scotland's 2014 health literacy action plan1 defines health literacy as:

‘people having the knowledge, skills, understanding and confidence to use health information, to be active partners in their care and to navigate health and social care systems’

The importance of health literacy has been highlighted more recently in an updated action plan for 2017-252 which describes it as important in improving health and reducing health inequalities and to achieving the WHO Sustainable Development Goals. A report by the Institute for Medicine in 2014 found that those with lower levels of health literacy were more likely to require hospitalisation and use emergency services.3 Further to this a systematic review of how general health literacy affects health outcomes found that low levels of health literacy were associated with reduced uptake of prevention based initiatives such as screening and immunisation programmes.4 Qualitative research has demonstrated an association between low health literacy and a sense of stigma or shame during healthcare consultations leading to reduced benefit to patients.5

The American Dental Association describes oral health literacy as ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate oral health decisions.6 Some models to enhance general health literacy have been developed but oral health literacy is still a relatively new research topic.7 Extrapolating from findings in general health literacy, one might assume that those with higher levels of oral health literacy have better oral health and oral health related outcomes.

The authors of this study aimed to explore whether there was an association between oral health literacy (OHL) and oral health behaviours, perception, knowledge and dental treatment outcomes. The question as defined in the paper was very broad and not focused on a specific population of interest. Despite this broad scope, the papers included in the study looked primarily at patients attending hospital based clinics, and it would have been reasonable to have limited the study to just this population if scoping work had suggested this was the broad base for the literature. Both adult and child patients were considered in this review which is an inherent problem as studies of children used the parent's OHL when considering the behaviours and outcomes associated with the children studied.

The search used to identify studies was comprehensive, including multiple search methods such as electronic database searches, grey literature searches and identification of papers from the reference list of the included studies. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were generally reasonable and easily justified, however the authors might have missed important studies by excluding qualitative studies and evaluative reports. Risk of bias assessments were carried out using previously validated instruments and appropriate stages of the review, including the screening of eligible studies, were undertaken independently by two reviewers.

In total 25 studies were included in the narrative synthesis and a meta-analysis was carried out on a small sub set of studies (n=3). Both the quality of the studies and the results were very mixed. Some included studies showed positive associations while others showed no evidence of association. This was across all outcomes and in all populations considered. The only outcome which showed consistently positive associations with OHL was oral health knowledge which is not overly surprising when OHL is defined as ‘the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate oral health decisions’.

The paper reports a meta-analysis for one single outcome based on three papers which were deemed homogeneous enough to be synthesised in this way. The results of the meta-analysis were inconclusive and provided no further weight of evidence to the paper than the narrative synthesis already conducted.

Despite a comprehensive literature search, variation in findings of studies included in this review highlighted inconsistencies in the evidence base. Although 25 studies were included only a few reported on each of the outcomes investigated by the review, with methodological issues, heterogeneity between studies and high risk of bias preventing definitive conclusions being reached. This review was therefore unable to clarify how oral health literacy may affect oral health behaviours, perception, knowledge or treatment related outcomes.

Overall, the results of this review were inconclusive and provided no concrete insight into the effect of oral health literacy on the outcomes described. The authors recognised the limitations of this study, including a number of the papers arising from the same research group. It does however have some value in highlighting the limitations in current research into oral health literacy and the need for more high quality studies in this field.

Practice point

-

It is important for clinicians to understand oral health literacy with respect to tailoring of oral health interventions and messages or improving oral health literacy amongst certain groups. For those designing health promotion interventions, it will also be useful to understand how oral health literacy affects the health of those targeted.

References

Scottish Government. Making it easy. A Health Literacy Action Plan for Scotland. 2014. Available at https://www.gov.scot/Resource/0045/00451263.pdf (accessed August 2018)

Scottish Government. Making it easier. A Health Literacy Action Plan for Scotland 2017-2025. 2017. Available at https://www.gov.scot/Resource/0052/00528139.pdf (accessed August 2018)

US Institute of Medicine, Committee on Health Literacy. Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA (eds). Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington DC: US Institute of Medicine; 2004

Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K . Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005

Easton P, Entwistle VA, Williams B . How the stigma of low literacy can impair patient-professional spoken interactions and affect health: insights from a qualitative investigation. BMC Health Serv Res 2013; 13: 319 doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-319

American Dental Association. Health literacy in dentistry. Public Programs 2018. Available at https://www.ada.org/en/public-programs/health-literacy-in-dentistry (accessed August 2018)

Sørensen K, Van den Broucke S . Fullam J et al. (HLS-EU) Consortium Health Literacy Project European. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Ramon Targino Firmino, Av Presidente Antonio Carlos, 6627- Pampulha, Belo Horizonte- MG 31270-901, Brazil. E-mail: ramontargino@gmail.com

Firmino RT, Martins CC, Faria LDS et al. Association of oral health literacy with oral health behaviours, perception, knowledge and dental treatment related outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Public Health Dent 2018; Mar 2. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12266. [Epub ahead of print]

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burns, J., McGoldrick, N. & Muir, M. Oral health literacy, oral health behaviours and dental outcomes. Evid Based Dent 19, 69–70 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401318

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401318