Key Points

-

The findings from this paper may be used for comparative purposes with other studies and against the national picture.

-

The findings complement the national review.

-

This study provides a valuable evidence base in response to a range of key issues in order to inform local workforce development.

-

The outcomes contribute to both local and wider strategies for ways forward in developing the dental workforce.

Abstract

Objective To explore opportunities for workforce development in NHS general dental services (GDS) in Shropshire and Staffordshire.

Method Secondary data sources were supplemented with a primary survey of GDS practices to build up a profile of the existing GDS workforce and its current capacity. Attitudes and perceptions on current workforce issues and potential solutions were gathered using a second survey and explored further through other qualitative techniques including interviews and a focus group discussion.

Results The results confirm that there is a shortage of dentists in the area, fuelled by multiple factors including the move from NHS to private work, the decision to retire early and a growing disillusionment with NHS policies and remuneration. Modelling of alternate approaches to future dental clinical needs highlighted the opportunity for meeting the consequent workforce demands through increased involvement of hygienists and therapists.

Conclusions This study has provided local evidence to inform dental service development in Shropshire and Staffordshire. It has provided a starting point for exploring new ways of working and will contribute towards a more effective implementation of new and evolving service strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper describes a project commissioned by the Shropshire and Staffordshire Workforce Development Confederation (WDC) in collaboration with local Primary Care Trusts (PCTs). The aim of the study was to provide a basis for addressing perceived local dental workforce problems. Fundamental to these perceptions were longstanding problems with access to routine NHS dental care, as evidenced by high call rates to NHS Direct, falling registration levels, a lack of practices taking on new NHS patients and complaints from residents. In addition PCTs were aware that the Options for change1 policy development would lead to them taking on commissioning responsibility for General Dental Services (GDS) and that they would need more information to support this.

Despite actions to improve the situation, adult registration rates within the area remain low; the Strategic Health Authority (SHA) ranked 22nd out of the 28 English SHAs in March 2004 with a take-up rate per 100 population of 38.0 compared with 46.5 for Midlands and The East NHS Area and 44.1 for England.2 Attempts by local NHS organisations to improve access had been reportedly frustrated by difficulties in recruiting new dentists to the area. The area has low numbers of dentists for the size of the population; a study in 2001 put the three then health authorities in the lowest quartile for numbers of dentists in England and Wales.3 A more recent analysis4 has confirmed this; dentists tending to be concentrated in affluent urban areas. Dental Access Centres (DACs) were established in all three areas under Personal Dental Service (PDS) arrangements after 1998. Three of the 10 PCTs within the area have subsequently been recognised as amongst the 16 PCTs with the greatest problems of access to NHS dentistry: they are currently working with the NHS Dentistry Support Team to address the issue.5,6,7 A fourth PCT was due to be visited by the team in November 2004.

A survey mounted in December 1999, focusing on the West Midlands, identified that a clear differentiation exists between Shire counties (generally less well-served) and urban areas.8 The evidence further suggested that while there was no sign of large scale de-registrations, major problems existed in the provision for patients not registered with a dentist, including emergency care. A 2001 survey of general dental practitioners (GDPs) in South Staffordshire9 also suggested that a significant number of dentists intended to retire early. While the service problems were clear, it was less clear what practical steps could be taken to address the workforce issues at the core of the access problems, particularly in the Shire counties.

As a consequence the purpose of the project developed into a broad exploration of issues and opportunities for workforce development in local NHS dentistry. It provided an opportunity to link local issues and opportunities to national proposals for revitalising NHS dentistry.1 Within the national proposals come recommendations for change in remuneration, practice size and roles for hygienists and therapists, all of which are directed towards a more effective development and mobilisation of the dental workforce.

The aims of the project were therefore to:

-

1

Profile the existing composition of the dental workforce and assess its capacity to meet local needs now and in the future

-

2

Explore perceptions about staffing shortfalls and the capacity to close this gap through general recruitment and local training, new ways of working and barriers to progress

-

3

Develop a picture of future requirements and how they could be met, taking into account the new strategic policies for NHS dentistry, workforce re-design and innovation in dental health care.

This was a timely study given the paucity of evidence surrounding the dental workforce in Shropshire and Staffordshire. It allowed both a depth and breadth of information to be gathered using primary and secondary sources of data, and a variety of methodological techniques. This work enabled issues outlined by previous dental workforce studies to be fully explored in this local context.

This paper presents an overview of the study, its key findings and their implications. Complementary findings emergent from specific methodological components will be reported in detail elsewhere.

Methods

A multi-method approach was required in order to meet the aims and objectives of the study. Quantitative information on dental practices, their characteristics and those of their staff were taken from secondary data sources and supplemented with a survey sent to all GDS practices. This provided information for workforce modelling. Some of this information was also mapped using a geographical information system (GIS) in order to provide a visual and spatial representation of the information. A range of qualitative techniques (a survey, semi-structured interviews and a focus group discussion) was used to capture attitudes and opinions on current workforce issues, and potential solutions. Open evening workshops were held to test conclusions arising from the quantitative modelling. The study was conducted between May 2002 and May 2003.

Information was collected for Shropshire and Staffordshire. The SHA is made up of the three former health authorities of North Staffordshire, South Staffordshire and Shropshire, and much of the information can still be disaggregated into the three areas. Results are presented separately for the three former health authority areas where there appear to be differences between them, and in total where patterns are similar.

In order to obtain a profile of the existing workforce, information was gathered initially from two secondary data sources. These were databases on dentists working in the GDS from the PCTs, and General Dental Council (GDC) electronic professional registers for dentists, hygienists and therapists. For each dentist in the area, the PCT databases provided information including gender, date of birth, position (owner/ associate) and practice postcode. All dentists/ hygienists/ therapists on the GDC registers with a postcode (practice/home) in Shropshire or Staffordshire were identified. The registers provided their name, registration address and qualifications. Neither source provided information about the number of hours worked.

This information was then supplemented by a quantitative survey of GDS practices. A self-administered questionnaire was sent to a senior dentist in each of the 59 GDS practices in North Staffordshire, 85 in South Staffordshire and 73 in Shropshire. The survey gathered data on staff who are not recorded on existing databases, in particular dental nurses and administrative staff. Data were also collected on the number of sessions worked per week by each staff sub-group providing an indicative measure of the whole-time equivalence (WTE) of the staff employed. It also included a range of other information, such as vacancy factors and turnover, needed to draw a comprehensive profile of the workforce.

The GIS methodology (ArcView) was used to illustrate information such as the number of dentists at each practice, and whether practices had a practice manager, vocational training position or vacancy for an associate. It was also possible to plot the number of dentists per population with measures of population density and deprivation.

To provide a framework for the collection and analysis of data, two separate models were designed. The first was a 'stock and flow' model to capture the characteristics of dental movement into, through and out of the dental services in Shropshire and Staffordshire. The second provided a vehicle for using existing demands for the service to forecast future workforce requirements under different conditions of skill-mixing between dentists, hygienists and therapists and comparing this with projections of future supply.

The profiling of the dental workforce was essentially a quantitative exercise. To provide a more comprehensive underlying picture required the collection and analysis of 'soft' information based on individual opinions, values and judgments.

The qualitative research activities provided a descriptive account of the attitudes and perceptions of the dental workforce. A self-administered postal survey was sent to all 481 dentists working in the GDS to obtain their views on workforce issues. The content of this survey was informed by earlier studies.8,10

The issues covered related to recruitment and retention, and perceptions were gathered using Likert scales of agreement to a series of themed attitudinal statements and a few open questions. The issues identified in the survey were explored in greater detail through 40 individual semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of 25 dentists in the GDS, three vocational trainees (VTs), three therapists, three hygienists, three nurses and three practice managers. The sampling criteria included age, gender, professional status, and geographical location. Finally the views of local PCT representatives were sought in the light of all the other information at a focus group discussion. Nine individuals were invited; their operational roles included primary care administrators and managers, dental practice advisors and those with responsibility for Personal Dental Services and Community Dental Services.

Qualitative survey data recorded using Likert scales were analysed using summary statistics. A content analysis approach was used for the open questions on the survey and for the semi-structured interviews and focus group discussion.

Results were shared at two open evening workshops at both Telford and Stafford, to which staff from all GDS practices in Shropshire and Staffordshire were invited to attend. The workshops were part presentation and part working groups of participants. They were used to test the conclusions arising from analysis of the quantitative data, to provide a practical context to the issues facing local dentistry and to explore the potential of different solutions to present and likely future problems.

In order to inform future strategy, the quantitative and qualitative findings were drawn together, and are presented by workforce issue in the results.

Results

Response rates

The quantitative survey of GDS practices returned a response rate of 70% (n = 151). For the attitudes and perceptions questionnaire, there was a response rate of 38% (n = 185). Interviews were conducted with 40 respondents split between the staff groups as planned. There were very few refusals to participate, but in the instances when a respondent declined, another respondent was identified with matching characteristics. Five PCT representatives attended the focus group discussion. The four open evening workshops were attended by 20-30 participants, who were primarily dentists, but also included hygienists, therapists and other staff.

Workforce profile

According to PCT records, there were 469 dentists working in the GDS across Shropshire and Staffordshire at the start of the study. Slightly greater numbers of dentists were recorded on the GDC register in or within 10km of the two counties (Table 1).

The distribution of the workforce as a whole (based on the GDS practice survey) is shown in Table 2. The unregistered support staff (dental nurses and administrative staff) made up 65% of the dental workforce.

Dentists

The proportion of women in the dentist workforce was 29% with greater numbers of women in the younger age groups (Table 3). The age distribution of dentists gives clear cause for concern. There are significant numbers in the area that may opt to retire early over the next five to 10 years. Overall nearly 30% of dentists were aged 50 or over, with 13% over 55 years old. Evidence from our qualitative work suggested that there was a likelihood that many of these dentists over 55 would retire early in the absence of any policy to retain them. It also indicated that the decision to retire early was influenced by the views that working in NHS dentistry was extremely stressful and that the levels of bureaucracy were too demanding. The most frequently cited main reason for early retirement was 'reached “burn-out”/worries about health'. The NHS was often described as a 'treadmill', with too much red tape and paperwork.

Hygienists and therapists

According to the GDC registers, there were 236 hygienists and 36 therapists in or within 10km of Shropshire and Staffordshire, although apart from the research team's survey, no data were available on whether or where they were currently working. There were 30-40% of practices not using the service provided by hygienists. At the time of the study, legislation had only just changed allowing therapists to work in GDS.

Nurses

Taking the wider workforce as a whole there was a substantial support workforce with dental nurses comprising just under 40% of the WTE clinical workforce. Nurses were available in all local practices although their level of formal training varied substantially. There was serious concern among dentists however over a shortage of qualified dental nurses.

Administrative staff

There was a relatively low ratio of one administrative worker to every dentist. The comparative figure for GPs is closer to a ratio of 2:1. Moreover, the distribution of practice managers was patchy, with up to 50% of practices reporting no designated practice manager. Subsequent workshop discussions with dentists suggested that the under-use of practice managers was due to a combination of a shortage of trained practice managers; limited understanding of the quantifiable benefits to be realised from using practice managers and a lack of accessible processes for sharing practice managers between small practices.

Service capacity

Approximately half the dental practitioners worked in small practices with only one or two dentists, and 21% were in single-handed practices. This is of particular significance since the smaller practices are felt to be most at risk of permanent closure when the practice owner decides either to move elsewhere or retire.

The registration rates, the proportion of the population registered with an NHS dentist, are shown in Table 4. The rates were all lower than the England and Wales average of 49%.2 Average NHS list sizes were higher in Staffordshire than Shropshire (Table 4). These can be compared to an average NHS list size for England and Wales of 1475.2 The findings from the practice survey on the reported proportion of time spent on NHS work, also shown in Table 4, were broadly consistent with these registration rates and list sizes.

The qualitative findings clearly confirmed that there was a deep dissatisfaction regarding the current remuneration system for NHS dentists, but also demonstrated that the move to private dentistry was influenced largely by the potential for greater financial benefits and the opportunity to provide a better quality service. As with reasons for early retirement, there were frequent references to the NHS treadmill, red tape and too much paperwork. There was also a strong belief that newly qualified dentists are driven to seek positions that offer good potential for career advancement and the scope for a substantial proportion of private work.

Current participation rates, ie the proportion of available time spent in surgery, amongst full time dental practitioners in the two counties were high (70-80%). Nevertheless, 29% of practices surveyed reported that a surgery room was only in use for up to two days per week, suggesting that there was at least some physical capacity for expansion.

The GIS work showed that there were approximately 3.0 registered dentists per 10,000 resident population across the two counties. Nationally, for England and Wales, average provision was significantly higher at 3.6. Areas of above average deprivation and population density in the two counties have generally still lower levels of provision.

Service development issues

Recruiting and retaining staff

The practice survey found significant turnover amongst several staff groups. Results showed that 25% of associate dentists and 31% of dental nurses left in the last year. Many clearly move between local practices, with 41% of associates that left and 52% of nurses staying within the same county.

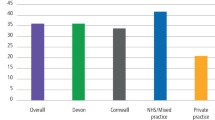

The practice survey sought data on the number of vacant posts subject to genuine attempts to recruit staff in the last year. The current vacancy factors for associates were 38%, 30% and 26% in North Staffordshire, South Staffordshire and Shropshire respectively. For hygienists, the current vacancy factors were 34% in North and South Staffordshire and 21% in Shropshire. The evidence of pressure of work on dental practitioners is demonstrated in the desire to recruit associate dentists and hygienists.

There was a clear perception amongst all participant groups from the qualitative work that there was a substantial shortage of NHS dentists in the local area. Dentists believed that there was a sufficiently poor socio-economic image of both counties that made it extremely difficult to recruit newly qualified dentists. They also believed that it was difficult to retain VTs once their training ended. However there were mixed views amongst dentists with respect to the advantages and disadvantages that vocational training positions can bring to a practice. Key factors which were perceived to be the causes of NHS dentist shortages included the growing move towards private dentistry and the intention amongst dentists to retire early.

Future requirements based on workforce modelling and new ways of working

Opportunities for the reallocation of workload were modelled and explored, once future service requirements had been estimated. Using North Staffordshire as an example, the population served by NHS dentistry was assumed to be the proportion of the resident population registered with an NHS dentist: 45% of 451,000 in North Staffordshire, giving a population served by NHS dentistry of 202,900. The expected number of visits per patient per annum was four, based on casemix data from the Dental Practice Board (DPB), giving a total of 812,000 visits per annum in North Staffordshire.

It was estimated that the North Staffordshire NHS dentistry population required 153 WTE dental clinicians to cover NHS work alone. This assumed that a reasonable workload per WTE is four patients an hour, for nine 3.5 hour sessions per week, and 42 weeks per year; ie 126 patients per week, or 5,292 NHS patient visits per year. Where modelling assumptions were required, judgements were made by the dental advisors to the project, and were supported when shared with participants at the workshops.

Not all of these clinicians need be dentists. Information on casemix, ie the percentage distribution of interventions in the seven treatment categories, as defined by the DPB and shown in Table 5, was apportioned to different clinical providers on the basis of competency to practise. Applying these figures to North Staffordshire suggested that 54% of visits should be to dentists, 31% to hygienists and 15% to therapists. This corresponded to a WTE requirement for 82 dentists, 24 therapists and 48 hygienists. The results for all three areas are shown in Table 6. A note of caution however; dentists expressed concerns over the change in legislation allowing therapists to work in the GDS. The concerns focused particularly on a lack of clarity of roles and that responsibility for treatment provided by a therapist would remain with dentists.

Discussion

This study has assessed the existing composition of the dental workforce, and the current GDS capacity in Shropshire and Staffordshire. It has addressed workforce development issues around recruiting and retaining staff, and future requirements, including alternative scenarios for service delivery using new ways of working.

The study has clearly confirmed that there is a shortage of dental staff in Shropshire and Staffordshire. However the modelling has shown that, under certain conditions, these additional staff need not be dentists, but could be hygienists and/ or therapists. Key factors contributing to shortages of dentists are the shift from NHS to private work and the decision to retire early; issues which are underpinned by a growing sense of disillusionment with the policy framework around dental service delivery and remuneration.

The multi-method approach used in the study enabled breadth and depth of information to be obtained. The surveys gathered valuable facts and opinions from a credible sample of dentists, while the interviews and the focus group discussion were able to provide a greater level of understanding of issues from a smaller response group, with the latter specifically involved in service planning. The triangulation of results from all aspects of the study has enabled greater reinforcement of findings. It is therefore possible to suggest more realistic, contextually relevant, ways forward for Shropshire and Staffordshire.

This was a local study, and while other areas of the UK that experience difficulty with access to NHS dental care may have similar problems, it is not possible to generalise widely the results of this study. In addition there may be issues of non-response bias. However the approach used is certainly transferable. The methodological framework described here could be appropriate for other researchers who wished to explore workforce profile and development issues in another geographical area. Given the current national concern regarding the provision of dental care, it is quite possible that others may wish to replicate elements of this study in their local setting.

The information obtained from the workforce profiling is in keeping with other studies. The national study by Seward10 reported that women make up 32% of the Dentists Register, with greater proportions of them in the younger age groups, which is consistent with findings here. A survey on the availability of primary dental care conducted in the West Midlands8 reported an overall response rate of 77%, which is similar to the practice survey response rate here. It also reported that an average of 29 hours was worked per contract, which is 8.3 sessions per week, and again consistent with our findings.

The NHS dental service is overstretched at present, and this local study showed no demonstrable spare capacity. There are high participation rates among dentists, and a below average dentist to population ratio. High vacancy factors and wastage rates were reported. Strategies to consider in order to maintain current workforce numbers need to focus on recruitment, retention and the possibilities for increasing the scope of vocational training. It is necessary to understand the reasons for the current behaviour of the workforce to address these issues. It is particularly important to consider the high proportion of small practices that are most at risk of permanent closure, given the current age structure. Not surprisingly, small practices tend to experience a greater negative impact from many of the problems presented in this paper.

There is a belief that the local area has a poor reputation and this deters potential dentists (including VTs) from working in the area. Factors potentially driving this situation include distance from dental schools and the relatively long distance that VTs have to travel to attend day release. Retention of dentists is certainly a problem, with several drains on the existing workforce: the shift from NHS to private work and early retirement. The shift from NHS to private work is not only due to dissatisfaction with the NHS remuneration system, and the potential for greater financial benefits in the private sector, but also so that dentists can spend more time with patients and provide a better quality service. Therefore increases in the fees-for-service would not solve all the problems. Exhaustion, stress and too much bureaucracy fuel the decision to retire early. These findings are consistent with the national picture: the shift away from NHS to private practice is well documented,11 as is the dissatisfaction regarding the current NHS remuneration system,1 which deters dentists from NHS practice. The move to new pay arrangements for GDPs which are not directly linked to individual items of treatment, has the promise, if successful, to improve retention of dentists within the GDS including deferred retirement. Many of the practitioners referred to 'burnout' under existing arrangements and hopefully the new arrangements will allow more varied working and thus reduce stress on dentists. The move to new contractual models is also likely to bring with it the potential for improving practice management capacity, such as was seen with medical practitioners in the past.

The nearest university training is in Birmingham and Manchester, producing about 125 registered dentists, and 28 hygienists and therapists per year. We believe this is inadequate to meet the current shortfall in Shropshire and Staffordshire. The picture is also bleak with regard to VT places with fewer than 20 local practices with VTs in-post. Hygienist and therapist capacity is planned to grown in line with the national programme but is unlikely to support a major expansion in this element of the workforce over the next five years. The lack of qualified dental nurses is equally problematic. Access to nurse training is difficult, with little support provided to enable existing staff to participate in distance learning programmes. There is a real need to enhance training capacity in the local area for all dental staff groups.

The scenarios modelled have provided estimates of the minimum number of dentists required, with the additional workload being met by hygienists and therapists. While the change in legislation allowing therapists to work in the GDS allows greater flexibility in the way the service is provided, it is important to be mindful of concerns that exist over this change. A key area of concern is the issue of who takes responsibility for the work done by therapists. In practical terms, there is a large shortfall in the number of therapists in the area compared to the number required if there were shifts in clinical service patterns, which blocks any significant shift in this direction in the short term. While there appears to be a surplus of hygienists, the hours worked and locations of work for the hygienists identified on the GDC register are unclear. These concerns also apply to therapists. In addition there are concerns over the cost effectiveness of dental therapists compared to dentists.12

Since this study was undertaken, the national dental workforce review has been published13 and it has been announced that 170 additional dental training places will be provided from 2005.14 Furthermore 1,000 dentists will be recruited, both internally and overseas, as an interim measure pending the impact of the additional trainees from 2010 onwards. These numbers seem minimal given the local analysis and will not address the regional imbalance unless some targeting of vacancies takes place. At the time of writing PCTs in the three areas were seeking to engage with Department of Health overseas recruiting initiatives. While the Office of Fair Trading15 called for further deregulation of dentistry, this is unlikely in the near future and the impact on access would be uncertain. PCTs are expected to take on full responsibility for commissioning all dental services from April 2006. Four of the PCTs in this study went on to work with the NHS dental support team as they continued to experience significant difficulties in ensuring access to NHS dentistry for their residents.

Conclusion

This study has provided substantial depth and breadth of information to inform dental service development in Shropshire and Staffordshire, and a methodology that is transferable to other localities. The study provides local evidence of the scale of problems that had previously only been reported anecdotally. The modelling of new ways of working gives a starting point for the future, while the opinions gathered will contribute towards a more effective implementation of evolving strategies. The evidence can also assist decision-makers as they address the feasibility of government proposals and policy and develop dental services.

References

Department of Health. NHS dentistry: Options for change. London: Department of Health, 2002.

Dental Practice Board. http://www.dpb.nhs.uk/

Moles DR, Frost C, Grundy C . Inequalities in availability of National Health Service general dental practitioners in England and Wales. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 548– 553.

Boulos MN, Phillips GP . Is NHS dentistry in crisis? 'Traffic light' maps of dentists distribution in England and Wales. Int J Health Geogr 2004; 3: 10. www.ij-healthgeographics.com/content/3/1/10. Accessed 10/6/04.

Department of Health. Further funding announced to tackle access to NHS dentists. Press release 2003/0476 25/11/03. London: DoH, 2003.

Department of Health. Streatham practice shows the way forward for NHS dentistry. Press release 2003/0476 12/8/03. London: DoH, 2003.

NHS Dentistry Support Team: Report February 2004. www.dpb.nhs.uk/mod_dentistry/documents/february_2004_report.pdf. Accessed 10/6/04.

West Midlands Regional Dental Public Health Group. Second survey on the availability of primary dental care - December 1999.

Morris J, Harrison R, Caswell M, Lunn H . The working patterns and retirement plans of general dental practitioners in a Midlands health authority. Prim Dent Care 2002; 9: 153– 156.

Seward M . Better opportunities for women dentists - a review of the contribution of women dentists to the workforce. London: Department of Health, 2001.

Buck D, Newton JT . The privatisation of NHS dentistry? A national snapshot of general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 115– 118.

Harris R, Burnside G . The role of dental therapists working in four personal dental service pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost-effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 491– 496.

Department of Health. Report of the Primary Care Dental Workforce Review. London: Crown Copyright, 2004. www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/60/76/04086076.pdf. Accessed 31/8/04.

Department of Health. The Secretary of State for Health: Written Ministerial Statement on NHS dentistry. 16/07/04.

Office of Fair Trading. The private dentistry market in the UK. www.oft.gov.uk/Market+investigations/Investigations/dentistry.htm. Accessed 31/8/04.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the other Consultants in Public Health in the project area, namely Dr Kate Taylor-Weetman and Mr Mike Prendergast for their assistance. We are very grateful to Mr Keith Mason (School of Physical and Geographical Sciences, Keele University) for his advice and contribution with respect to the GIS mapping components of this work. We also recognise the assistance of the stakeholder group. We thank all dental staff that participated in the study. Funding was received from the Shropshire and Staffordshire Workforce Development Confederation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hornby, P., Stokes, E., Russell, W. et al. A dental workforce review for a Midlands Strategic Health Authority. Br Dent J 200, 575–579 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813588

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813588

This article is cited by

-

Modelling workforce skill-mix: how can dental professionals meet the needs and demands of older people in England?

British Dental Journal (2010)

-

Fear of litigation

British Dental Journal (2006)