Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the psychometric properties of a subset of International Spinal Cord Injury Basic Pain Data Set (ISCIBPDS) items that could be used as self-report measures in surveys, longitudinal studies and clinical trials.

Setting:

Community.

Methods:

A subset of the ISCIBPDS items and measures of two validity criteria were administered in a postal survey to 184 individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) and pain. The responses of the participants were evaluated to determine: (1) item response rates (as an estimate of ease of item completion); (2) internal consistency (as an estimate of the reliability of the multiple-item measures); and (3) concurrent validity.

Results:

The results support the utility and validity of the ISCIBPDS items and scales that measure pain interference, intensity, site(s), frequency, duration and timing (time of day of worst pain) in individuals with SCI and chronic pain. The results also provide psychometric information that can be used to select from among the ISCIBPDS items in settings that require even fewer items than are in the basic data set.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain is a significant problem in many individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI).1, 2

To better understand the nature of pain in individuals with SCI and the efficacy of treatment, valid and reliable pain measures are needed. There is also a need to standardize pain assessment in SCI research to allow for more direct comparisons between studies.

The International Spinal Cord Injury Basic Pain Data Set (ISCIBPDS) was developed to provide a standardized way of collecting a minimal yet clinically relevant set of measures of up to three pain problems in individuals with SCI across settings and countries.3 The ISCIBPDS is intended to be used by health-care professionals with expertise in SCI and should be used in conjunction with the International SCI Core Data Set,4 which includes demographic information and neurological status.

Although designed to be administered by a health-care professional, self-report versions of the ISCIBDIPS items may be useful in clinical practice, surveys and longitudinal studies, or in treatment outcome studies. To support their use, however, their psychometric properties need to be evaluated. The purpose of this study was, therefore, to evaluate the utility, reliability and validity of a subset of the ISCIBPDS items that can be used when (1) self-report measures are needed and (2) the clinician or researcher wishes to use standardized measures that can be compared with published findings.

Materials and methods

Participants

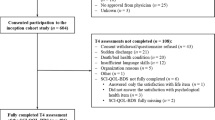

Participants were 184 adults with SCI and pain who completed a postal survey. Participants were paid $25 for returning a completed questionnaire. Study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from each participant. Potential participants came from a pool of individuals from earlier studies who had expressed a willingness to be contacted for additional studies. Of 308 consent forms and surveys that were mailed, 203 (66%) were completed and returned. Of these, 184 (91%) were from participants who reported that they experienced persistent pain in the past 3 months.

The 184 participants were primarily white (90.8%) men (74.5%) who had an average SCI duration of 19.2 years (range, 2–63 years). Average age was 54.4 years (range, 21–87 years) and most reported completing at least a high school education (95.2%). Only 25.6% reported that they were working full or part time. In all, 38% reported complete SCI, and the most common levels of injury were at C5–C7 and T10–L1 (35.9% each).

Measures

International Spinal Cord Injury Basic Pain Data Set items

Some of the ISCIBPDS items (for example, classification of neuropathic versus nociceptive pain) are not appropriate as self-report items. However, the majority of the ISCIBPDS items can be used as self-report measures. Those that required no modification included an item about number of pain problems, a 0–10 Numerical Rating Scale of pain intensity, and two items regarding pain frequency and pain duration for each of up to three pain problems.

Two of the ISCIBPDS items did require modification to make them easier for patients providing information without the supervision of a health-care provider. First, to simplify the assessment, each of the six pain interference items was asked only once, regarding pain in general (as opposed to about each of up to three pain problems). Second, the response options for the item asking about pain location(s) were reduced from 50 to 8 options (see Appendix).

Validity criteria

Two validity criterion measures were included in the survey, one assessing psychological functioning and one assessing sleep problems. Psychological functioning was assessed using the five-item Mental Health scale of the SF-365 which has shown validity and high levels of reliability in numerous samples of healthy and chronically ill populations.5 Sleep problems were assessed using the six-item Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Problem Index, which has shown validity and good reliability in a large normative sample.6

Data analysis

Four sets of analyses were performed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the ISCIBPDS items and scales. First, we computed the frequency of missing responses to each item. Second, we computed internal consistency coefficients using Cronbach's for the six ISCIBPDS interference items, and for two different subsets of these items (the alphas for the item subsets were computed to examine the possibility that reliable scales may be created by fewer items). Coefficients ranging from 0.61 to 0.80 may be considered to be ‘moderate’, and from 0.81 to 1.0 ‘substantial’.7 We considered coefficients in the moderate-to-substantial range to be acceptable.

Next, we computed Pearson correlation coefficients among the ISCIBPDS interference items and scales and pain intensity ratings, and between all of the ISCIBPDS items and scales and the two validity criterion measures. We hypothesized that if the ISCIBPDS items and scales were valid: (1) the interference measures would be at least moderately (r=0.30 or greater) and significantly associated with pain intensity; (2) items assessing pain frequency and pain duration would be significantly associated with both pain interference and average pain intensity; and (3) ISCIBPDS measures of pain interference, pain intensity, pain duration and pain frequency would have negative associations with psychological functioning and positive associations with the severity of sleep problems. An alpha level of 0.01 was set for these analyses to control for the risk of type I errors because of multiple comparisons.

Finally, we evaluated the extent to which information regarding pain intensity from the worst, second worst and third worst pain problem would predict pain interference and the validity criterion measures using three regression analyses. In these analyses, we entered the average pain intensity ratings for the worst, second worst and third worst pain problem in steps 1, 2 and 3, respectively. We determined a priori that the importance of obtaining intensity ratings for two pain problems would be supported if the second worst pain intensity rating made a significant contribution to the prediction of the criterion variables when the worst pain intensity rating was controlled, and that the importance of obtaining ratings for three pain problems would be supported if the third worst pain intensity rating made a significant contribution to the prediction of the criterion variables when the worst and second worst pain problem intensity ratings were controlled. P⩽0.05 was considered statistically significant for the regression analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The means and s.d.s of the continuous ISCIBPDS self-report items and scales are presented in Table 1, and the rates of responding to each response category for the ISCIBPDS items are listed in Table 2. Table 2 also indicates how the responses to each item were coded. As can be seen, the means of most of the interference items and scales tended to be near 2.5 (range, 1.97–2.60) on the 0–6 scales, indicating a moderate amount of average pain interference for the sample. Consistent with an earlier research, most (79.3%) of the participants reported that they had more than one pain problem. The frequency of missing responses was <2% for all of the items, and the response category with the highest response rate was the ‘unpredictable’ response associated with the question regarding the time of day that pain is most severe (56.0–66.2%).

Internal consistency

We computed three pain interference scales from the six ISCIBPDS interference items: (1) a six-item total inference scale (Total Interference); (2) a three-item composite made up by a subset of the MPI-SCI items8 asking about limits in general activity, changes in recreational and social activity, and changes in satisfaction with family activities (LSF Interference; for Limits in activity and changes in Social and recreational activity and Family related activity); and (3) a three-item composite made up of items (original to the ISCIBPDS) asking about interference with day-to-day activities, mood and sleep (AMS Interference; for interference with Activities, Mood and Sleep). The internal consistency coefficients associated with these three scales were 0.94, 0.91 and 0.89, respectively.

Concurrent validity

Associations between interference and intensity ratings

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the three 0–10 Numerical Rating Scale pain intensity ratings; and the three interference scales and six interference items are presented in Table 3. As can be seen, all of the coefficients were positive, all but one of the coefficients were statistically significant at P>0.01, and all but one of the coefficients were >0.30.

Associations between reported pain frequency and duration and interference

The correlation coefficients between (1) the frequency of the worst and second worst pain problem and the duration of the worst and second worst pain problem and (2) the Total Interference score were all positive. However, these coefficients were weak (rs range=0.13–0.24), and only two of the four were statistically significant (P<0.01). The correlation coefficients between (1) reported pain frequency and pain duration of the third worst pain problem and (2) the Total Interference score were very weak and negative (rs=−0.07 and −0.01, respectively).

Associations between interference, intensity, frequency, duration and the validity criteria measures

The correlation coefficients between (1) the ISCIBPDS interference scales, pain intensity ratings, pain frequency items and pain duration items and (2) the two validity criterion measures are presented in Table 4. All three interference scales showed strong associations with both validity criteria in the expected directions. However, the three-item AMS Interference scale was more strongly associated with the criterion measures than was the three-item LSF Interference scale. Responses to the intensity, days of pain and pain duration items for the worst and second worst pain problems showed the hypothesized patterns of associations with the validity criterion; all four coefficients associated with these intensity items and two of the four coefficients associated with the days of pain items were statistically significant (P<0.01). However, although the pattern of associations for third worst pain problem and the criteria variables were in the expected directions, only one was statistically significant (P<0.01). Moreover, neither the days of pain nor duration of pain items for the third worst pain showed the expected pattern of associations with the criteria variables.

Regression analyses predicting interference and criterion variables from worst, second worst and third worst intensity ratings

The results of the three regression analyses predicting the Total Interference score and the two validity criterion measures are presented in Table 5. As a group, the pain intensity ratings of the worst, second worst and third worst pain problems were significantly associated with pain interference (F(3,85)=11.35 and P<0.001), and the worst and second worst pain intensity ratings both made significant contributions to this criterion. The three pain intensity ratings were also significantly associated with sleep problems as a group (F(3,85)=4.02 and P=0.01), with the worst and second worst intensity ratings showing a significant association with sleep problems. As a group, the three pain intensity ratings were not significantly associated with psychological functioning. Interestingly, however, the intensity rating of the third worst pain problem was a significant, and unique, predictor of psychological functioning after the worst and second worst pain intensity ratings were entered into the equation.

Discussion

The current findings support the concurrent validity of the self-report items and scales of the ISCIBPDS. There were very few missing responses to any of the items, suggesting that the items were understandable enough to elicit a response. Thus, the ISCIBPDS items and scales may prove very useful as self-report measures of key pain-related domains in clinical practice and research.

The Total Interference scale showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α=0.94) suggesting the possibility that all six items may not be required to assess the pain interference domain. Moreover, the validity of the interference items and scales was supported by their strong associations with the pain intensity ratings and with the validity criterion. Some differences in the validity coefficients were found, however, with the AMS Interference scale showing stronger associations with the validity criteria than the LSF Interference scale. This finding may be related to the wording of the items, given that the AMS items ask specifically about interference with activity, mood and sleep, whereas the LSF items do not specifically ask about interference, per se. These results suggest that, if a shorter interference scale is ultimately adopted for standard use, the three-item AMS Interference scale may prove most useful. However, more research in additional samples would be useful before any revisions of the ISCIBPDS items are performed.

The validity of the worst, second worst and third worst pain intensity ratings was strongly supported, with moderate-to-strong associations found between these items and the pain interference items and scales and validity criteria. This finding is consistent with the strong support for the validity of numerical scales of pain intensity in many studies and populations.9 Strong support was also found for asking patients to report on the intensity of at least their worst and second worst pain problems, as each of these made statistically significant and independent contributions to the prediction of the validity criteria. Limited support was also found for assessing the intensity of the third pain problem given the trend for this rating to contribute to the prediction of sleep problems, and its significant and independent contribution to the prediction of psychological functioning.

There was somewhat less support for the validity of the two pain duration items (days of pain and duration of pain incidents). Given our clinical observation that the nature and amount of pain duration differs between musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain, it is possible that the associations between the duration and criterion variables may have been attenuated because that our sample contained individuals with both neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that in survey studies of heterogeneous patients, the duration items may not be as important (at least as predictors of patient functioning) as the intensity items, although they clearly are necessary for diagnostic purposes.

The limitations of this study include the fact that it is based on a single sample that was self-selected (that is, were willing to complete surveys). In addition, some of the original ISCIBPDS items were modified (simplified), and the sequence of items was altered (the interference items were administered first in this self-report version). Although we do not anticipate that these changes altered the psychometric properties of the items to a large extent, their effect on the reliability and validity of the items is not known. For these reasons, replication of the findings in additional samples is needed to determine their generalizability. Additional limitations include the lack of diagnostic information regarding type of pain (for example, neuropathic versus nociceptive) problems in the sample, as well as the fact that the validity criteria used were limited to measures of psychological functioning and sleep problems. It would be useful to determine the extent to which the ISCIBPDS items are associated with other validity criteria, as well as to determine the moderating effects, if any, that pain type has on the validity of the ISCIBPDS items and scales.

Despite the study's limitations, the findings support the utility and validity of the self-report version of the ISCIBPDS items for assessing pain in individuals with SCI in clinical practice and research settings. The items assess domains that are important to assess in clinical practice, such as pain interference, location, intensity, frequency and duration. Interference and intensity must be measured if clinicians wish to monitor the effects of treatments over time. Pain location, frequency and duration information is necessary for diagnosis. Although the self-report version of ISCIBPDS is quite brief, clinicians could make it even more practical by assessing the treatment outcome domains (interference and intensity) at each assessment, and the other domains useful for diagnosis less often.

The brevity of the self-report version of the ISCIPBPDS also indicates that it may be particularly useful in research settings in which assessment burden is an issue. This includes survey studies that might include additional questionnaires or measures, or longitudinal studies in which a minimal number of items are needed to help minimize subject attrition. Researchers may choose to administer the location, frequency and duration domains only once (for descriptive purposes), but administer the interference and intensity items over time in clinical trials and longitudinal survey studies. Of particular importance, the adoption and use of the ISCIPBDS items by researchers would also enhance the ability to compare findings across studies and populations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Finnerup NB, Jensen TS . Spinal cord injury pain—mechanisms and treatment. Eur J Neurol 2004; 11: 73–82.

Ullrich PM . Pain following spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2007; 18: 217–233.

Widerström-Noga E, Biering-Sørensen F, Bryce T, Cardenas DD, Finnerup NB, Jensen MP et al. The international spinal cord injury pain basic dataset. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 818–823.

DeVivo M, Biering-Sørensen F, Charlifue S, Noonan V, Post M, Stripling T et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 535–540.

Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B . SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation guide. Quality Metric Incorporated: Lincoln, RI, 2000.

Hays R, Stewart A . Sleep measures. In: A Stewart, J Ware (eds). Measuring Functioning and Well Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Duke University Press: Durham, NC, 1992, pp 235–259.

Shrout PE . Measurement reliability and agreement in psychiatry. Stat Methods Med Res 1998; 7: 301–317.

Widerström-Noga EG, Cruz-Almeida Y, Martinez-Arizala A, Turk DC . Internal consistency, stability, and validity of the spinal cord injury version of the multidimensional pain inventory. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006; 87: 516–523.

Jensen MP . Pain assessment in clinical trials. In: H Wittink and D Carr (eds). Pain Management: Evidence, Outcomes, and Quality of Life in Pain Treatment. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2008, pp 57–88.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Center for Rehabilitation Research (grant no. P01 HD33988) and the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, US Department of Education (grant no. H133N00003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

International Spinal Cord Injury Basic Pain Data Set items modified for self-report use.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jensen, M., Widerström-Noga, E., Richards, J. et al. Reliability and validity of the International Spinal Cord Injury Basic Pain Data Set items as self-report measures. Spinal Cord 48, 230–238 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.112

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.112

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessment of pain symptoms and quality of life using the International Spinal Cord Injury Data Sets in persons with chronic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)

-

Treatment of at-level spinal cord injury pain with botulinum toxin A

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2019)

-

International spinal cord injury bowel function basic data set (Version 2.0)

Spinal Cord (2017)

-

The CanPain SCI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Rehabilitation Management of Neuropathic Pain after Spinal Cord: screening and diagnosis recommendations

Spinal Cord (2016)

-

Common data elements for spinal cord injury clinical research: a National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke project

Spinal Cord (2015)