Abstract

Amplification of the 11q13 region is one of the most frequent aberrations in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck region (HNSCC). Amplification of 11q13 has been shown to correlate with the presence of lymph node metastases and decreased survival. The 11q13.3 amplicon carries numerous genes including cyclin D1 and cortactin. Recently, we reported that FADD becomes overexpressed upon amplification and that FADD protein expression predicts for lymph node positivity and disease-specific mortality. However, the gene within the 11q13.3 amplicon responsible for this correlation is yet to be identified. In this paper, we compared, using immunohistochemical analysis for cyclin D1, FADD and cortactin in a series of 106 laryngeal carcinomas which gene correlates best with lymph node metastases and increased disease-specific mortality. Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that high expression of cyclin D1 (P=0.016), FADD (P=0.003) and cortactin (P=0.0006) predict for increased risk to disease-specific mortality. Multivariate Cox analysis revealed that only high cortactin expression correlates with disease-specific mortality independent of cyclin D1 and/or FADD. Of genes located in the 11q13 amplicon, cortactin expression is the best predictor for shorter disease-specific survival in late stage laryngeal carcinomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Current methods to predict the outcome of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients mainly involve clinicopathological parameters such as tumour size, differentiation grade and presence of lymph node metastasis. Patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas (LSCC) have not shown an increase in 5-year survival rates over the last 30 years (Almadori et al, 2005). Therefore, other parameters such as molecular markers that are able to more accurately predict the outcome of disease, are needed.

A frequent molecular event in HNSCC is amplification of the 11q13 region (36%) (Schuuring, 1995; Freier et al, 2006). Amplification of this region in HNSCC has been associated with decreased survival (Akervall et al, 1995; Meredith et al, 1995), increased distant metastasis (Namazie et al, 2002) and lymph node metastasis (Chen et al, 2004; Hermsen et al, 2005; Xia et al, 2007). It is believed that amplification increases gene dosage and expression of genes within the amplified region (amplicon) (Albertson, 2006). Recently, we reported that the commonly amplified region is located at 11q13.3 and contains at least six genes (cyclin D1, TAOS1, FGF19, FADD, PPFIA1 and cortactin) that are overexpressed when amplified (Gibcus et al, 2007b). We concluded that the selection for tumour cells with the 11q13.3 amplicon during tumorigenesis could be based on the increased doses of one or more of these genes. We proposed FADD as a possible candidate for this selection, since FADD showed the best correlation between DNA amplification and increased expression (Gibcus et al, 2007b). Furthermore, FADD protein expression correlated with disease specific mortality (DSM) in a series of late stage laryngeal carcinomas. FADD protein expression was independent of lymph node metastasis and patients with both high FADD protein expression and lymph node metastasis had the worst prognosis for survival (Gibcus et al, 2007b). However, although FADD is a prognostic marker for increased mortality, we can not exclude that other genes within the 11q13 region are (also) involved.

The most frequently studied genes within the 11q13.3 region are cyclin D1 and cortactin (Schuuring, 1995). Overexpression of cyclin D1 at both protein and RNA level have been linked to poor prognosis in numerous studies (Akervall et al, 1997; Yu et al, 2005; Higuchi et al, 2007). Cortactin amplification was related to increased lymph node stage, advanced disease stage and reduced survival (Rodrigo et al, 2000). Cortactin mRNA expression (Luo et al, 2006) and protein expression (Rothschild et al, 2006) have been correlated to increased lymph node metastasis.

In summary, FADD, cyclin D1 and cortactin expression may each be involved in processes resulting in increased lymph node metastasis and in poor prognosis. Because the prognostic value of these genes has not been evaluated within the same group of patients simultaneously, we have performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) on 167 patients with late stage LSCC. Since lymph node metastases have been shown to be an important prognostic factor for DSM, we assessed the additional prognostic value of cyclin D1, FADD and cortactin in late stage LSCC.

Materials and methods

Patient inclusion

For immunohistochemical analysis we selected 167 patients diagnosed with a squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx, previously used for IHC of FADD. Patient material and available clinico-pathological data were obtained from the University Medical Center Groningen (n=56), The Netherlands Cancer Institute–Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek Hospital (n=62), the Instituto Universitario de Oncología del Principado de Asturias (n=22) and the Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands (n=28). Successful staining for all three antibodies was examined on 120 patients. Sufficient follow-up was available for 106 of 120 patients. In the other 61 cases follow-up was short or unavailable, material was lost in the IHC-process or, no or too few tumour cells were present in the tissue block. The remaining patient group (n=106) consisted mainly of larger tumours: T1 (n=8; 8%), T2 (n=22; 21%), T3 (n=31; 29%) and T4 (n=45; 42%) that were either treated with surgery, radiotherapy or a combination of both treatments. Patients who did not die had a median follow-up of 72 months, whereas patients who died had a median follow-up of 16 months. The clinical characteristics of the 106 cases were comparable to the characteristics of the total group of 167 patients (see Table 1).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry for cyclin D1 was performed as previously described (de Boer et al, 1995; Takes et al, 1998). For the immunostaining of cortactin we used a commercially available antibody (clone 30/cortactin from BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) that recognizes all cortactin isoforms and can be applied on archival material. IHC for FADD on the larger series of 167 LSCC was reported earlier (Gibcus et al, 2007b). Ki67 expression was used as a marker for cell proliferation. Paraffin-embedded, formalin-fixed sections of laryngeal carcinoma were deparaffinized and antigen retrieval was performed by overnight incubation at 80°C in Tris–HCL pH=9.0 for Ki-67 and FADD, or heating in a microwave oven for 15 min in EDTA pH=6.0 for cortactin, or heating in a microwave oven in Tris–HCL pH=9.0 for 30 min for cyclin D1. After blocking endogenous peroxidases with 0.3% H2O2, the sections were stained for 1 h with an antibody against cyclin D1 (sp4, 1 : 50, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), FADD (1 : 100, BD Transduction Laboratories), cortactin (clone 30/cortactin; 1 : 1000, BD Transduction Laboratories) and Ki-67 (MIB-1, 1 : 350; DAKO, Heverlee, Belgium). Secondary and tertiary antibodies were diluted 1 : 100 in 1% BSA-PBS complemented with 1% AB-serum or EnVision (DAKO). Antibodies were precipitated using 3, 3′ diaminobenzidine tetrachloride as a substrate and the slides were counterstained using routine haematoxylin treatment. In parallel, a haematoxylin and eosin stained slide was scored by a pathologist (JEvdW) to verify tumour content.

Scoring of the immunohistochemical staining of Cyclin D1 and ki-67 was based on the percentage of positive tumour cells as reported previously. Scoring for cortactin was also based on the percentage of cells with high cytoplasmic expression. Expression levels similar or lower than the intensity in the surrounding normal tissue (used as the internal reference for staining) were considered as low cortactin expressors and those with increased intensity as high expressors. The intermingled lymphocytes served as a negative control. For FADD the intensity of the positively stained tumour cells was scored and divided into two different categories; low expressors (−, +) and high expressors (++, +++) as described previously (Gibcus et al, 2007b).

Antibodies against PPFIA1 (LIP.1) (Serra-Pages et al, 1995) and FGF19 (mab969; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA) appeared to be inappropriate for IHC analysis (data not shown) and antibodies against FLJ42258 and TAOS1 are presently not available.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using version 14.0 of the SPSS software package. Cutoff percentages for dichotomization of the data were determined for cyclin D1 and cortactin using the median percentage of stained cells; 23% for nuclear cyclin D1 and 13% for cytoplasmic cortactin staining (Table 1). Associations between IHC staining patterns were identified by logistic regression. Prognostic value was evaluated per staining using Kaplan–Meier curves and univariate Cox regression for DSM to discern between deaths without evidence of disease and death of disease. A multivariate Cox regression model including cyclin D1, FADD, cortactin and lymph node status and treatment were based on univariate significance. All tests were two-sided and P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

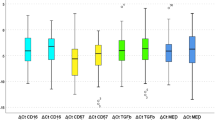

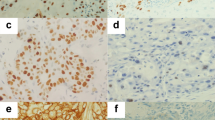

To study which gene within the 11q13. 3 region is responsible for the clinical outcome, we evaluated the expression of cyclin D1, FADD and cortactin using a series of 106 LSSCs previously stained for FADD expression (Table 1 and Figure 1). The other four consistently overexpressed genes in the 11q13 amplicon (Gibcus et al, 2007b) were not investigated further because no antibodies were available (TAOS1 and FLJ42258) or appeared to be inappropriate for immunohistochemistry on archive material (PPFIA1 and FGF19) (data not shown). Firstly, we determined whether there was a link between amplification and protein expression. For this purpose we immunostained a subset of 16 cases in which amplification was determined previously (Gibcus et al, 2007a). Carcinomas with 11q13 amplification showed high protein expression levels in 8/8 cases for cyclin D1, 8/9 cases for FADD and 8/9 for cortactin (Table 2). In addition, the high expression of cyclin D1 and cortactin in 5/8 and 3/7 cases without amplification, respectively, and FADD only in 1/7 suggest that FADD correlates best with amplification (Table 2). The frequencies of high expression without amplification indicate that increased expression of cyclin D1 and cortactin are caused by mechanisms other than amplification.

Immunohistochemical staining for cyclin D1, cortactin and FADD. A case without amplification and low cyclin D1 (A), FADD (B) and cortactin (C) expression and a case with amplification and high expression of cyclin D1 (E), FADD (F) and cortactin (G). Expression of ki-67 was unrelated to expression of the 11q13.3 genes (D, H).

Secondly, we evaluated whether protein expression of FADD, cyclin D1 and cortactin (Figure 1) were related to increased DSM and lymph node metastasis. Logistic regression for expression of FADD, cyclin D1 and cortactin was performed on dichotomized groups. The resulting odds ratios (OR) implicated that cortactin positivity (OR=11.2; 95% CI, 4.6–27.1) and cyclin D1 positivity (OR=3.82; 95% CI, 1.7–8.4) were related to FADD expression (data not shown). The relation between protein expression and increased DSM was determined using univariate Cox regression. High expression of FADD, cyclin D1 and cortactin was related to increased DSM (Table 3). Furthermore, lymph node metastasis, a marker for worse prognosis, was also related to increased DSM, whereas age, gender and tumour size were not. Treatment was also related to increased DSM. However, the choice of treatment is based on the prognosis obtained by classical prognostic factors (such as lymph node metastasis). Cell division rates, determined by immunohistochemical staining for Ki-67 levels (Figure 1D and H), were not correlated to increased DSM in univariate Cox regression. Although lymph node metastasis has been reported as an important clinical prognosticator (Eiband et al, 1989; Gasparotto and Maestro, 2007), cortactin expression (HR=13.14; 95% CI, 3.04–56.87; P=0.0006) correlated stronger to increased DSM than lymph node metastasis (HR=3.16; 95% CI, 1.29–7.75; P=0.012) (Table 3).

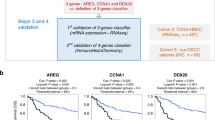

A multivariate Cox regression model including cortactin, cyclin D1, FADD, treatment and lymph node metastasis showed that cortactin expression (HR=8.46; 95% CI, 1.63–43.88; P=0.011) and lymph node metastasis (HR=3.96; 95% CI, 1.30–12.06; P=0.015) were predictors for increased DSM, whereas FADD and cyclin D1 were not (Table 4A). Furthermore, in the multivariate analysis treatment with surgery, radiotherapy or a combination of both was not related to increased DSM (Table 4A). To assess whether cortactin and lymph node metastasis were independent prognostic factors, a multivariate Cox regression, using only cortactin expression and lymph node metastasis, was performed. Both cortactin expression and lymph node metastasis were significantly related to increased DSM (Table 4B), implying they are both prognostic factors. However, Kaplan–Meier analysis for cortactin, within lymph node positive tumours only, revealed a remarkable difference (Log-rank: P=0.00002) in DSM between cortactin-positive and cortactin-negative cases (Figure 2).

Discussion

Cortactin predicts poor survival in late stage laryngeal carcinomas

Amplification of the 11q13.3 region has been related to a worse prognosis (Meredith et al, 1995; Xie et al, 2006). Furthermore, expression of cortactin, cyclin D1 and more recently FADD (Gibcus et al, 2007b), have been described separately as potential predictors for increased disease-related mortality, for lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis. Yet, the effect of overexpression due to amplification in head and neck carcinomas have not been examined for these proteins within the same group of patients.

We show that both cortactin and lymph node metastasis are good predictors for DSM using a multivariate model independent of cyclin D1 and FADD (Table 4A). This implies a correlation between lymph node metastasis and cortactin, as suggested previously (Rothschild et al, 2006). However, also within the lymph node metastasis positive group, high cortactin expression identifies patients with significantly increased DSM, whereas low cortactin expression identifies a group of patients with a good prognosis for survival. These data indicate that cortactin expression is independent of lymph node metastasis (Figure 2).

Cortactin, a regulator of ARP2/3-mediated actin polymerization, is known to contribute to tumour cell growth and cancer progression (Weed and Parsons, 2001). Downregulation of cortactin in cancer cell lines decreases the cellular motility and ability to migrate (Rothschild et al, 2006; van Rossum et al, 2006) whereas overexpression resulted in an increased invasive potential (van Rossum et al, 2003; Rothschild et al, 2006). In addition to the effect on cell migration by mediating actin polymerization and cell adhesion (van Rossum et al, 2006), cortactin might also influence cell migration and metastasis by anoikis resistance and PI3K/Akt signalling (Luo et al, 2006; Luo and Wang, 2007). Because of these biological functions and its overexpression due to DNA amplification, cortactin is the most likely gene within the 11q13.3 amplicon to mediate the worse clinical behaviour of late stage LSCC with 11q13 amplification.

A role for multiple genes in the biology of 11q13.3 amplification

To evaluate the significance of 11q13.3 amplification it is imperative to discern the genes selected upon by amplification based overexpression (‘drivers’) from those whose overexpression is apparent, yet unrelated to tumour progression (‘hitchhikers’). Gene by gene functional analyses have revealed that cyclin D1 (Opitz et al, 2001; Nelsen et al, 2005), FADD (Alappat et al, 2003; Chen et al, 2005) and cortactin (van Rossum et al, 2003; Luo et al, 2006) are potentially able to enhance cancer development. However, these studies do not account for the effect of multiple genes located within the 11q13.3 amplicon. By revealing a relationship to prognosis, we show that cortactin is a potential driver, independent of cyclin D1 and FADD. Cyclin D1 and FADD were not significantly related to short DSM in a multivariate Cox regression model in the present study. However, our present study contains mainly high T-stage tumour and the univariate significance of cyclin D1 and FADD implies a link to amplification. The 11q13.3 amplicon is 1.7 Mb in size and contains 13 genes in almost all HNSCC cases with 11q13.3 amplification (Gibcus et al, 2007b). Therefore, multiple genes are enabled to increase their copy number and expression by 11q13.3 amplification (Freier et al, 2006; Gibcus et al, 2007a). Considering the different functions of cortactin, cyclin D1 and FADD it would be interesting to see whether these genes, coamplified in the same tumour, have a function at specific stages of tumorigenesis. Increased expression of cyclin D1 is detected at early stages of tumorigenesis and found prior to amplification (Izzo et al, 1998). Interestingly, cyclin D1 overexpression enhances cell division and results in genomic instability (Nelsen et al, 2005). On the other hand, cortactin overexpression might induce an increase in the invasive potential affecting later stages of cancer development (this study). Furthermore, cortactin overexpression was reported to inhibit the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of the epidermal growth factor receptor, resulting in a sustained ligand-induced epidermal growth factor receptor activity (van Rossum et al, 2005). Overexpression promoted resistance to the EGFR kinase inhibitor gefitinib (Timpson et al, 2007) indicating that cortactin not only affects invasive but also therapeutic responsive properties of HNSCC cancers. Finally, FADD expression and phosphorylation have been shown to affect cell cycle progression (Alappat et al, 2003) and resistance to chemotherapy (Shimada et al, 2004). Moreover, treatment with combinations of chemotherapy and radiation (Forastiere et al, 2003; Vermorken et al, 2007) might be affected by FADD expression due to 11q13 amplification, as hypothesized previously (Gibcus et al, 2007b). Because amplification was proven an early event in tumorigenesis (Izzo et al, 1998; Burnworth et al, 2006), and amplicons are inherited during tumorigenesis, we hypothesize that the high occurrence of 11q13.3 amplification enables multiple genes to be beneficial to tumour progression at distinct stages of tumour development.

In summary, our data indicate that cortactin is a good predictor for disease-related mortality in late stage LSCC. Furthermore, within lymph node positive tumours, cortactin expression can be used to distinguish between a good and a bad prognosis.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Akervall JA, Jin Y, Wennerberg JP, Zatterstrom UK, Kjellen E, Mertens F, Willen R, Mandahl N, Heim S, Mitelman F (1995) Chromosomal abnormalities involving 11q13 are associated with poor prognosis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer 76: 853–859

Akervall JA, Michalides RJ, Mineta H, Balm A, Borg A, Dictor MR, Jin Y, Loftus B, Mertens F, Wennerberg JP (1997) Amplification of cyclin D1 in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and the prognostic value of chromosomal abnormalities and cyclin D1 overexpression. Cancer 79: 380–389

Alappat EC, Volkland J, Peter ME (2003) Cell cycle effects by C-FADD depend on its C-terminal phosphorylation site. J Biol Chem 278: 41585–41588

Albertson DG (2006) Gene amplification in cancer. Trends Genet 22: 447–455

Almadori G, Bussu F, Cadoni G, Galli J, Paludetti G, Maurizi M (2005) Molecular markers in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: towards an integrated clinicobiological approach. Eur J Cancer 41: 683–693

Burnworth B, Popp S, Stark HJ, Steinkraus V, Brocker EB, Hartschuh W, Birek C, Boukamp P (2006) Gain of 11q/cyclin D1 overexpression is an essential early step in skin cancer development and causes abnormal tissue organization and differentiation. Oncogene 25: 4399–4412

Chen G, Bhojani MS, Heaford AC, Chang DC, Laxman B, Thomas DG, Griffin LB, Yu J, Coppola JM, Giordano TJ, Lin L, Adams D, Orringer MB, Ross BD, Beer DG, Rehemtulla A (2005) Phosphorylated FADD induces NF-kappaB, perturbs cell cycle, and is associated with poor outcome in lung adenocarcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12507–12512

Chen YJ, Lin SC, Kao T, Chang CS, Hong PS, Shieh TM, Chang KW (2004) Genome-wide profiling of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Pathol 204: 326–332

de Boer CJ, Schuuring E, Dreef E, Peters G, Bartek J, Kluin PM, Van Krieken JH (1995) Cyclin D1 protein analysis in the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 86: 2715–2723

Eiband JD, Elias EG, Suter CM, Gray WC, Didolkar MS (1989) Prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Am J Surg 158: 314–317

Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, Pajak TF, Weber R, Morrison W, Glisson B, Trotti A, Ridge JA, Chao C, Peters G, Lee DJ, Leaf A, Ensley J, Cooper J (2003) Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 349: 2091–2098

Freier K, Sticht C, Hofele C, Flechtenmacher C, Stange D, Puccio L, Toedt G, Radlwimmer B, Lichter P, Joos S (2006) Recurrent coamplification of cytoskeleton-associated genes EMS1 and SHANK2 with CCND1 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 45: 118–125

Gasparotto D, Maestro R (2007) Molecular approaches to the staging of head and neck carcinomas (review). Int J Oncol 31: 175–180

Gibcus JH, Kok K, Menkema L, Hermsen MA, Mastik M, Kluin PM, Van Der Wal JE, Schuuring E (2007a) High-resolution mapping identifies a commonly amplified 11q13.3 region containing multiple genes flanked by segmental duplications. Hum Genet 121: 187–201

Gibcus JH, Menkema L, Mastik MF, Hermsen MA, de Bock GH, van Velthuysen ML, Takes RP, Kok K, varez Marcos CA, Van Der Laan BF, van den Brekel MW, Langendijk JA, Kluin PM, Van Der Wal JE, Schuuring E (2007b) Amplicon mapping and expression profiling identify the fas-associated death domain gene as a new driver in the 11q13.3 amplicon in laryngeal/pharyngeal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13: 6257–6266

Hermsen M, Alonso GM, Meijer G, van DP, Suarez NC, Marcos CA, Sampedro A (2005) Chromosomal changes in relation to clinical outcome in larynx and pharynx squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Oncol 27: 191–198

Higuchi E, Oridate N, Homma A, Suzuki F, Atago Y, Nagahashi T, Furuta Y, Fukuda S (2007) Prognostic significance of cyclin D1 and p16 in patients with intermediate-risk head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with docetaxel and concurrent radiotherapy. Head Neck 29 (10): 940–947

Izzo JG, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Li XQ, Ibarguen H, Lee JS, Ro JY, El Naggar A, Hong WK, Hittelman WN (1998) Dysregulated cyclin D1 expression early in head and neck tumorigenesis: in vivo evidence for an association with subsequent gene amplification. Oncogene 17: 2313–2322

Luo ML, Shen XM, Zhang Y, Wei F, Xu X, Cai Y, Zhang X, Sun YT, Zhan QM, Wu M, Wang MR (2006) Amplification and overexpression of CTTN (EMS1) contribute to the metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by promoting cell migration and anoikis resistance. Cancer Res 66: 11690–11699

Luo ML, Wang MR (2007) CTTN (EMS1): an oncogene contributing to the metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Res 17: 298–300

Meredith SD, Levine PA, Burns JA, Gaffey MJ, Boyd JC, Weiss LM, Erickson NL, Williams ME (1995) Chromosome 11q13 amplification in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Association with poor prognosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 121: 790–794

Namazie A, Alavi S, Olopade OI, Pauletti G, Aghamohammadi N, Aghamohammadi M, Gornbein JA, Calcaterra TC, Slamon DJ, Wang MB, Srivatsan ES (2002) Cyclin D1 amplification and p16(MTS1/CDK4I) deletion correlate with poor prognosis in head and neck tumors. Laryngoscope 112: 472–481

Nelsen CJ, Kuriyama R, Hirsch B, Negron VC, Lingle WL, Goggin MM, Stanley MW, Albrecht JH (2005) Short term cyclin D1 overexpression induces centrosome amplification, mitotic spindle abnormalities, and aneuploidy. J Biol Chem 280: 768–776

Opitz OG, Suliman Y, Hahn WC, Harada H, Blum HE, Rustgi AK (2001) Cyclin D1 overexpression and p53 inactivation immortalize primary oral keratinocytes by a telomerase-independent mechanism. J Clin Invest 108: 725–732

Rodrigo JP, Garcia LA, Ramos S, Lazo PS, Suarez C (2000) EMS1 gene amplification correlates with poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res 6: 3177–3182

Rothschild BL, Shim AH, Ammer AG, Kelley LC, Irby KB, Head JA, Chen L, Varella-Garcia M, Sacks PG, Frederick B, Raben D, Weed SA (2006) Cortactin overexpression regulates actin-related protein 2/3 complex activity, motility, and invasion in carcinomas with chromosome 11q13 amplification. Cancer Res 66: 8017–8025

Schuuring E (1995) The involvement of the chromosome 11q13 region in human malignancies: cyclin D1 and EMS1 are two new candidate oncogenes–a review. Gene 159: 83–96

Serra-Pages C, Kedersha NL, Fazikas L, Medley Q, Debant A, Streuli M (1995) The LAR transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase and a coiled-coil LAR-interacting protein co-localize at focal adhesions. EMBO J 14: 2827–2838

Shimada K, Matsuyoshi S, Nakamura M, Ishida E, Kishi M, Konishi N (2004) Phosphorylation of FADD is critical for sensitivity to anticancer drug-induced apoptosis. Carcinogenesis 25: 1089–1097

Takes RP, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Schuuring E, Litvinov SV, Hermans J, Van Krieken JH (1998) Differences in expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes in different sites of head and neck squamous cell. Anticancer Res 18: 4793–4800

Timpson P, Wilson AS, Lehrbach GM, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA, Daly RJ (2007) Aberrant expression of cortactin in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells is associated with enhanced cell proliferation and resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor gefitinib. Cancer Res 67: 9304–9314

van Rossum AG, de Graaf JH, Schuuring-Scholtes E, Kluin PM, Fan YX, Zhan X, Moolenaar WH, Schuuring E (2003) Alternative splicing of the actin binding domain of human cortactin affects cell migration. J Biol Chem 278: 45672–45679

van Rossum AG, Gibcus J, van der WJ, Schuuring E (2005) Cortactin overexpression results in sustained epidermal growth factor receptor signaling by preventing ligand-induced receptor degradation in human carcinoma cells. Breast Cancer Res 7: 235–237

van Rossum AG, Moolenaar WH, Schuuring E (2006) Cortactin affects cell migration by regulating intercellular adhesion and cell spreading. Exp Cell Res 312: 1658–1670

Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van HC, Gorlia T, Mesia R, Degardin M, Stewart JS, Jelic S, Betka J, Preiss JH, van den WD, Awada A, Cupissol D, Kienzer HR, Rey A, Desaunois I, Bernier J, Lefebvre JL (2007) Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med 357: 1695–1704

Weed SA, Parsons JT (2001) Cortactin: coupling membrane dynamics to cortical actin assembly. Oncogene 20: 6418–6434

Xia J, Chen Q, Li B, Zeng X (2007) Amplifications of TAOS1 and EMS1 genes in oral carcinogenesis: association with clinicopathological features. Oral Oncol 43: 508–514

Xie X, Clausen OP, Boysen M (2006) Correlation of numerical aberrations of chromosomes X and 11 and poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 132: 511–515

Yu Z, Weinberger PM, Haffty BG, Sasaki C, Zerillo C, Joe J, Kowalski D, Dziura J, Camp RL, Rimm DL, Psyrri A (2005) Cyclin d1 is a valuable prognostic marker in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 11: 1160–1166

Acknowledgements

We thank BFAM van der Laan and JA Langendijk from the University Medical Center Groningen (Groningen, the Netherlands), MA Hermsen and CA Álvares Marcos from the Instituto Universitario de Oncología del Principado de Asturias (Oviedo, Spain), MLF van Velthuysen and MWM van den Brekel from The Netherlands Cancer Institute–Antoni Van Leeuwenhoek Hospital (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and RP Takes from the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center (Nijmegen, the Netherlands). We thank Dr Q Medley (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA) for providing the LIP.1 antibody. This work is financially supported by the Dutch foundations ‘De Drie Lichten’, the ‘Maurits and Anna de Kock Foundation’, the ‘Jan Kornelis de Cock Stichting’, the Groningen University Institute for Drug Exploration (GUIDE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gibcus, J., Mastik, M., Menkema, L. et al. Cortactin expression predicts poor survival in laryngeal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 98, 950–955 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604246

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604246

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

PRMT5 promotes cancer cell migration and invasion through the E2F pathway

Cell Death & Disease (2020)

-

The chromosome 11q13.3 amplification associated lymph node metastasis is driven by miR-548k through modulating tumor microenvironment

Molecular Cancer (2018)

-

miR-182 suppresses invadopodia formation and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting cortactin gene

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2018)

-

Nucleus Accumbens-Associated 1 Contributes to Cortactin Deacetylation and Augments the Migration of Melanoma Cells

Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2011)

-

Nucleating actin for invasion

Nature Reviews Cancer (2011)