Abstract

Advanced ovarian carcinoma in early progression (<6 months) (AOCEP) is considered resistant to most cytotoxic drugs. Gemcitabine (GE) and oxaliplatin (OXA) have shown single-agent activity in relapsed ovarian cancer. Their combination was tested in patients with AOCEP in phase II study. Fifty patients pre-treated with platinum–taxane received q3w administration of OXA (100 mg m–2, d1) and GE (1000 mg m–2, d1, d8, 100-min infusion). Patient characteristics were a : median age 64 years (range 46–79),and 1 (84%) or 2 (16%) earlier lines of treatment. Haematological toxicity included grade 3–4 neutropaenia (33%), anaemia (8%), and thrombocytopaenia (19%). Febrile neutropaenia occurred in 3%. Non-haematological toxicity included grade 2–3 nausea or vomiting (34%), grade 3 fatigue (25%),and grade 2 alopecia (24%). Eighteen (37%) patients experienced response. Median progression-free (PF) and overall survivals (OS) were 4.6 and 11.4 months, respectively. The OXA–GE combination has high activity and acceptable toxicity in AOCEP patients. A comparison of the doublet OXA–GE with single-agent treatment is warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

With platinum taxane-based chemotherapy and debulking surgery, 70–80% of patients with advanced ovarian cancer are free of clinical disease (Kerbrat et al, 2001). Although primary chemotherapy achieves high response rates, about 75% of patients will subsequently relapse with incurable disease (Lhomme et al, 2004). Relapsed patients can be classified into one of three categories, according to the therapy-free interval (TFI) between the end of platinum-based chemotherapy and relapse. Those with TFI >6 months generally have relatively chemo-sensitive tumours that may respond to platinum therapy (platinum-sensitive disease) (Markman and Hoskins, 1992). In contrast, patients with TFI <6 months or no response to initial therapy (chemo-resistant or -refractory disease) have an extremely poor outcome (Eisenhauer et al, 1997). The prognosis of patients who progress during first-line chemotherapy or who experience an early relapse (treatment-free interval <6 months) is extremely poor, with <5% long-term disease-free survival (Eisenhauer et al, 1997; Gordon et al, 2001). In these cases, standard treatment consists of single-agent regimens for palliation and disease control.

Oxaliplatin (OXA) is a diaminocyclohexane platinum derivative non-cross resistant to cisplatin. Oxaliplatin–DNA adducts are not recognised by the proteins of the mismatch repair system (Fink et al, 1997). This may explain the activity of OXA in platinum-resistant ovarian cancers (Fink et al, 1996; Raymond et al, 2002). In a randomised study of 86 relapsed ovarian cancer patients, OXA at a dose of 130 mg m–2 q3w has yielded median response rates and time to progression similar to those of paclitaxel (Piccart et al, 2000). Gemcitabine (GE) is an antimetabolite that inhibits DNA synthesis and blocks DNA repair pathways, a modulation that may be useful in overcoming platinum resistance.

The combination of OXA and GE is synergistic in vitro (Raymond et al, 2002). We hypothesised that this combination might provide more effective therapy for patients with relapsed ovarian cancer. The present multicentre phase II trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity profile of OXA 100 mg m–2, d1, combined with GE 1000 mg m–2, d1 and d8, every 3 weeks in patience with advanced ovarian carcinoma in early progression (AOCEP).

Patients and methods

Objectives

The primary objective of the present study was to assess the anti-tumour activity of the OXA–GE combination in AOCEP patients. The main criterion for efficacy was objective response rate; secondary criteria were time to progression, response duration, and overall survival (OS). Our secondary objective was to determine the type, severity, and frequency of adverse events associated with OXA–GE treatment in these patients. The study design was an open, non-comparative, prospective phase II study.

The study was carried out according to good clinical practice guidelines, in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by local ethics committees. Approval was gained from local review boards, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant before inclusion. An independent monitoring institute was responsible for data control.

Patients' eligibility

Eligibility criteria were: age >18 years; histologically confirmed diagnosis of advanced ovarian cancer; recurrent ovarian cancer treated with one or two earlier lines of platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, the last one consisting of a carboplatin–paclitaxel combination; measurable or evaluable disease documented by imaging according to the response evaluation criteria for solid tumours (RECIST), and blood CA 125 level >40 UI; progression of disease during first-line treatment, or treatment-free interval before inclusion <6 months; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score <2; adequate haematological and organ functions; and written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria were: previous treatment with >2 lines of chemotherapy, previous total abdominal radiotherapy; brain or meningeal metastasis; grade >1 peripheral neuropathy according to the National Cancer Institute—Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI—CTC) version 2.0; severe cardiac dysfunction or uncontrolled hypertension; previous or concurrent malignancy other than ovarian cancer (with the exception of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia); concurrent serious, uncontrolled medical (including bowel occlusion or subocclusion) or psychiatric disease; previous treatment with either OXA or GE; glomerular filtration rate calculated according to the Cockroft–Gault formula <60 ml min–1, total bilirubin concentration >1.25 × upper normal limit, liver transaminases >2.5 × upper normal limit, absolute neutrophil count <2.0 × 109 l–l, and platelet count <100 × 109 l–l.

Treatment plan and drug administration

In all eligible patients treatment was administered through a central venous catheter: GE 1000 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8, administered over 100 min (10 mg m–2 min–1) after dilution in 250 ml normal saline, and OXA 100 mg m–2 on day 1, administered over 2 h 30 min after GE infusion after dilution in 250 ml of 5% glucose. All patients received standard antiemetic prophylaxis. Treatment was repeated every 21 days if blood counts returned to normal levels (neutrophil >1.5 × 109 l–l and platelets >100 × 109 l–l) and non haematological toxicity resolved to grade <1.

This regimen was given for a minimum of two cycles in the absence of disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or patient refusal. An evaluation of response was performed after two courses to determine whether the treatment should be continued, then repeated every two cycles. After six courses, the patients could continue therapy for three further cycles if, in the opinion of the attending physician, further clinical benefit could be expected.

Dose modifications

Treatment delays or dose modifications were decided based on NCI—CTC toxicity grading performed on each treatment day.

Haematological toxicity

Patients with neutropenic fever, grade 4 neutropaenia lasting >7 days or grade 4 thrombocytopaenia could continue treatment with a reduction of one dose level for each drug (OXA 85 mg m–2 on day 1 and GE 800 mg m–2 day–1 on days 1 and 8). The use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was then authorised, at the physician's discretion.

In case of recovery to an absolute neutrophil count of ⩾1.5 × 109 l–l or more and a platelet count >100 × 109 l–lin ⩽ 7 days, OXA and GE doses were reduced by one dose level. Any delay of >14 days in any course of treatment necessitated patient withdrawal from the study.

Day 8 of GE administration was suppressed if blood counts on that day showed an absolute neutrophil count of <0.5 × 109 l–l and a platelet count of <50 × 109 l–l. Day 8 dose of GE was reduced to 600 mg m–2 if blood counts on that day showed an absolute neutrophil count between 0.5 × 109 l–l and 1.5 × 109 l–l, and or a platelet count between 50 × 109 l–l and 100 × 109 l–l.

Non-haematological toxicity

Oxaliplatin was reduced to 85 mg m–2 in case of grade 1 peripheral neurotoxicity, to 65 mg m-2 in case of grade 2, and stopped in case of grade 3. It was discontinued in patients with grade 3 hypersensitivity reaction. Gemcitabine was reduced to 800 mg m–2 in case of grade >2 mucositis.

Patients who required more than two dose reductions of the same drug were withdrawn from the study treatment. When dose reduction was required, no subsequent dose escalation was allowed.

Evaluation of response and survival

Procedures for disease evaluation included standard physical examination and CA 125 level determination at each cycle, as well as computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis and two-view chest X-ray every two courses. Objective responses were evaluated using the RECIST (Therasse et al, 2000). In the absence of measurable disease, serologic response was determined according to CA 125 level kinetics using GCIG criteria (Vergote et al, 2000).

Duration of response was measured from the time of initial documented response to the first sign of disease progression. Overall survival was evaluated by measuring the interval from the beginning of treatment to the date of last follow-up or date of death, whichever occurred first. Time to progression was defined as the time from the date of treatment to documentation of tumour progression.

Determination of toxicity

Toxicity was evaluated using the NCI—CTC scale, version 2.0. All documented side effects were included, regardless of their relationship to study treatment. Haematological toxicity was evaluated weekly by complete blood count, whereas non-haematological toxicity was assessed before each treatment cycle. Chemotherapy was administered when the patient's neutrophil count was >1.5 × 109 l–l, and the platelet count >100 × 109 l–l.

Criteria for withdrawal from the study

Patients were removed from the study for any of the following reasons: (i) evidence of progressive disease after a minimum of two cycles of therapy; (ii) development of unacceptable toxicity; (iii) patient's refusal or inability to comply with protocol requirements.

Statistical analysis

A multi-stage phase II Fleming design was used to test whether the efficacy rate (response rate) was at least 20%, which we viewed as clinically promising, or at most 5%, which we viewed as not clinically promising (Fleming, 1982). With 45 evaluable patients, this trial had 90% power to detect an efficacy of 20% with a 0.05 level of significance. Interim analysis was performed after the first 15 and 30 patients. As we expected a 10% rate of ineligibility, the total number of patients planned for inclusion in the study was 50. The primary end-point of our study was objective response (CR plus PR). The response rate was calculated from all included patients based on the intention-to-treat principle, with determination of the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Survival rates and time to progression were analysed by the Kaplan–Meier method using SPSS® version 10.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

From May 2001 to May 2002, 50 patients were enrolled into the study. Patient characteristics are described in detail in Table 1. The median age was 64 years (range 46–79). All patients received a platinum–taxane regimen as first-line treatment. A majority of them had received only one earlier line of chemotherapy. Of the eight patients treated in the third line, five had received earlier treatment with carboplatin alone, one with topotecan, one with carboplatin followed by anti-aromatases, and one with a combination of anthracyclins, paclitaxel and carboplatin. Overall, half of the patients had measurable disease, whereas 46% had no measurable disease but elevated levels of CA 125.

One patient, who did not receive any study treatment owing to rapid clinical deterioration due to bowel obstruction, was excluded from all statistical evaluations.

Treatment

A median of six cycles (range, 1–9) was administered. Twenty-six (52%) of the 50 patients received the planned six cycles. The major cause for early discontinuation was disease progression in 17 patients, whereas seven patients did not complete the study because of adverse events (three patients), death without disease progression (two patients: one pulmonary embolism, one myocardial infarction), patient or physician decision (two patients).

The median dose of GE on day 1 remained close to 1000 mg m–2 for all 211 cycles administered. Of the 422 doses of GE planned, 37 (8.8%) were omitted (D8) and 57 (13.5%) were reduced, mainly because of neutropaenia, with a relative mean dose intensity of 85%. Of the 211 doses of OXA, none (0%) was omitted and 19 (9%) were reduced, mainly because of neurotoxicity. The median dose of OXA gradually decreased from 100 mg m–2 at cycle one to 96.8 mg m–2 at cycle six, with a relative mean dose intensity of 93%.

Clinical response

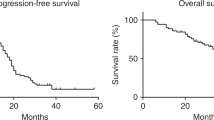

The overall response rate at the end of treatment (six cycles) was 37% (95% CI, 24–52%) (Table 2). With a median follow-up of 16 months, the median progression-free survival (PFS) for the whole group was 4.6 months (range 0.3–10.4), and the median OS was 11.4 months (range 0.9–27) (Figure 1). The objective response rate in patients with measurable disease was 31% (n=26). In patients with only CA 125 assessable disease (n=23), the response rate evaluated according to CA 125 GCIG criteria was 43%. Interestingly, no PFS differences were seen according to the method of response evaluation: patients with partial or complete response evaluated with the clinical RECIST criteria had a PFS of 6.8 months vs 6.5 months for those who were evaluated with GCIG serological criteria. Patients with stable disease had a PFS of 4.9 and 4.2 months according to clinical and serological evaluation, respectively. Finally, progressive patients had a very poor median PFS of 1.4 months.

Although the trial was not designed to evaluate treatment activity in the different subsets of patients, we analysed response rates according to the treatment-free interval. For the five patients who had undergone progression under prevoius chemotherapy, no response to the GE–OXA combination was observed. The response rate was 44% (4/9 patients) for patients who relapsed between 0 and 3 months after previous therapy, and 42% (14/33 patients) for those who relapsed in the 3–6-month interval.

Toxicity

A total of 211 chemotherapy cycles were administered to the 50 enrolled patients (median 6; range 1–8). Haematological side effects represented the main toxicity of the GE–OXA combination (Table 3). Blood transfusions were required in seven patients (12%) and platelet transfusions in two. Nine patients (18%) were treated with epoetin. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor administration, which was given only in case of G4 neutropaenia accompanied with fever or persisting >7 days, was necessary for eight patients (16%), and two of them were hospitalised.

The main non-haematological toxicities are summarised in Table 4. No grade 4 non-haematological toxicity was observed. Neuropathy occurred in 14 patients, but in only four of them (7%) symptoms were severe enough to compromise the activities of daily living and only one patient required discontinuation of treatment. Alopecia was not evaluated as most of the patients presented with pre-existing alopecia at enrolment because of earlier treatments. There were no unexpected non-haematological toxicities.

Discussion

The identification of new drug combinations is a major challenge to improve the anti-tumour activity and toxicity profile of chemotherapy in patients with advanced tumours. This phase II study shows that the combination of GE and OXA is active in earlier treated patients with advanced ovarian cancer refractory to platinum–taxane administration, and achieves an overall response rate of 37% (95% CI, 24–52%). These results are encouraging when compared with other chemotherapeutic agents, that is, liposomal pegylated doxorubicin or topotecan and weekly paclitaxel, or GE used alone, which achieve objective overall response rates of only 10–20% in clinical trials conducted in the same setting (Gordon et al, 2001; Markman et al, 2006; Ferrandina et al, 2008).

The regimen used in the present trial is derived from the phase I study conducted by Mavroudis et al in patients with advanced solid tumours with increasing doses of GE 1000–1600 mg m–2 on days 1 and 8, combined with OXA 60–120 mg m–2 on day 8, repeated every 21 days. The dose-limiting toxicities were grade 3–4 neutropaenia, thrombocytopaenia and asthaenia (Mavroudis et al, 2000). The doses of GE and OXA used in our study were 25% lower than those recommended in the phase I study by Mavroudis et al to account for the increased toxicity of chemotherapy in the subset of refractory or resistant ovarian cancer patients. The regimen was remarkably well tolerated by our patients regarding haematological, digestive, and renal toxicities, the major toxic reactions being neutropaenia and peripheral neuropathy. The once every 3 weeks schedule of administration allowed to maintain treatment dose intensity, with 93% of planned cycles effectively administered at the planned dose. The main cause of treatment delay was haematological toxicity. Cumulative non-haematological toxicities were asthaenia and paraesthesia, as earlier reported with GE and OXA, respectively (Mavroudis et al, 2000; Faivre et al, 2002). No bleeding and rare sepsis episodes (3%) were observed, and only two patients required platelet transfusion. Digestive toxicity was easily manageable with classical anti-emetics. As OXA has no renal toxicity, treatment could be given on an out-patient basis.

Other schedules of the GE–OXA combination have been tested in phase I (Mavroudis et al, 2000; Gandara et al, 2001; Faivre et al, 2002) and phase II trials in different diseases and lines of treatment (Table 5). Two main schedules have been reported: concurrent administration of GE and OXA once every 2 weeks or once every 3 weeks (with GE given at days 1 and 8). If grade 3–4 haematological toxicity seems slightly more frequent with the 3-weekly regimen (>40% vs <20%), grade 2–3 peripheral neuropathy is clearly more frequent with the every 2-week schedule (>20% vs <10%), giving the opportunity to the physician and the patient to choose the more appropriate schedule as a function of earlier toxicity and late adverse effects of earlier treatments.

The combination of GE and OXA has been reported to show activity in ovarian cancer both in earlier treated (Faivre et al, 2002; Raspagliesi et al, 2004; Germano et al, 2007; Harnett et al, 2007) and in first-line treated (Steer et al, 2006) patients. Platinum-resistant or platinum-refractory patients treated with the OXA–GE combination have been reported to experience response rates between 20 and 26% (Raspagliesi et al, 2004; Harnett et al, 2007) with median PFS and OS of 5.0 and 9.2 months, respectively. (Raspagliesi et al, 2004; Harnett et al, 2007). The results reported in the present study fall in the same range as those of earlier reports.

The last, but not least, question to be discussed is the benefit of the combination over single-agent therapy for this subset of very poor prognosis patients. Our non-randomised study cannot provide a clear-cut answer to this fundamental question. Several studies in resistant ovarian cancer patients have failed to find a median PFS or OS advantage of combinations of doxorubicin or epirubicin with paclitaxel over paclitaxel alone, or of doublets including topotecan over topotecan alone, suggesting that non-platinum single-agent therapy might be the most appropriate treatment in this setting (Bolis et al, 1999; Buda et al, 2004; Sehouli et al, 2008). The median time to progression of 4.6 months and the median OS of 11.4 months in resistant or refractory patients treated with OXA and GE in our study also appear comparable to survival durations reported in earlier trials of liposomal pegylated doxorubicin, topotecan or weekly paclitaxel used as single agents (Gordon et al, 2001; Markman et al, 2006). However, median PFS and OS, in contrast to disease control and quality of life, may not be the most relevant end-points for trials conducted in patients with refractory or resistant ovarian cancer. If we consider the entire study population, the GE–OXA combination induced response or stable disease in 63% of the cases, allowing prolonged disease control with acceptable side effects in a majority of patients. The high response rate reported with the GE–OXA regimen in our patients as well as in other studies might be of value in a selected population of treatment-resistant patients who complain of symptoms and need rapid relief. This should be confirmed in more adapted trials in which long-term improvement of symptoms could be a relevant end-point to compare the benefits of combination with those of single-agent therapy. The GE–OXA combination has shown significant response rates, both in the nine patients with TFI between 0 and 3 months (44% overall response rate) and in the 33 patients who relapsed between 3 and 6 months after treatement (42% response rate), thus encouraging its use in patients with symptomatic disease. This high activity of OXA–GE should, however, be balanced against the increased toxicity of the combination compared with single-drug regimens. A comparison of the duration of disease control and patient quality of life achieved with OXA–GE or non-platinum agents used as single agents is warranted.

Finally, our multicentre experience of the OXA–GE combination in patients with resistant ovarian cancer is close to that reported in other types of platinum-refractory tumours (Faivre et al, 2002; Franciosi et al, 2003; Pectasides et al, 2004). Despite experimental (Bergman et al, 1996) and clinical evidence of synergism between these two drugs, their optimal administration, either sequential or concurrent, remains to be determined in resistant ovarian cancer patients.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Bergman AM, Ruiz van Haperen VW, Veerman G, Kuiper CM, Peters GJ (1996) Synergistic interaction between cisplatin and gemcitabine in vitro. Clin Cancer Res 2: 521–530

Bolis G, Parazzini F, Scarfone G, Villa A, Amoroso M, Rabaiotti E, Polatti A, Reina S, Pirletti E (1999) Paclitaxel vs epidoxorubicin plus paclitaxel as second-line therapy for platinum-refractory and -resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 72: 60–64

Buda A, Floriani I, Rossi R, Colombo N, Torri V, Conte PF, Fossati R, Ravaioli A, Mangioni C (2004) Randomised controlled trial comparing single agent paclitaxel vs epidoxorubicin plus paclitaxel in patients with advanced ovarian cancer in early progression after platinum-based chemotherapy: an Italian Collaborative Study from the Mario Negri Institute, Milan, G.O.N.O. (Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest) group and I.O.R. (Istituto Oncologico Romagnolo) group. Br J Cancer 90: 2112–2117

Eisenhauer EA, Vermorken JB, Van Glabbeke M (1997) Predictors of response to subsequent chemotherapy in platinum pretreated ovarian cancer: a multivariate analysis of 704 patients [see comments]. Ann Oncol 8: 963–968

Faivre S, Le CT, Monnerat C, Lokiec F, Novello S, Taieb J, Pautier P, Lhomme C, Ruffie P, Kayitalire L, Armand JP, Raymond E (2002) Phase I–II and pharmacokinetic study of gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and ovarian carcinoma. Ann Oncol 13: 1479–1489

Ferrandina G, Ludovisi M, Lorusso D, Pignata S, Breda E, Savarese A, Del Medico P, Scaltriti L, Katsaros D, Priolo D, Scambia G (2008) Phase III trial of gemcitabine compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in progressive or recurrent ovarian cancer. JClin Oncol 26: 890–896

Fink D, Nebel S, Aebi S, Zheng H, Cenni B, Nehme A, Christen RD, Howell SB (1996) The role of DNA mismatch repair in platinum drug resistance. Cancer Res 56: 4881–4886

Fink D, Zheng H, Nebel S, Norris PS, Aebi S, Lin TP, Nehme A, Christen RD, Haas M, MacLeod CL, Howell SB (1997) In vitro and in vivo resistance to cisplatin in cells that have lost DNA mismatch repair. Cancer Res 57: 1841–1845

Fleming TR (1982) One-sample multiple testing procedure for phase II clinical trials. Biometrics 38: 143–151

Franciosi V, Barbieri R, Aitini E, Vasini G, Cacciani GC, Capra R, Camisa R, Cascinu S (2003) Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin: a safe and active regimen in poor prognosis advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer 41: 101–106

Gandara DR, Edelman MJ, Lara PN, Lau DH (2001) Gemcitabine in combination with new platinum compounds: an update. Oncology (Williston Park) 15: 13–17

Germano D, Rosati G, Manzione L (2007) Gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin (GEMOX) as salvage treatment in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer refractory or resistant to platinum: a single institution experience. J Chemother 19: 577–581

Gordon AN, Fleagle JT, Guthrie D, Parkin DE, Gore ME, Lacave AJ (2001) Recurrent epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin vs topotecan. J Clin Oncol 19: 3312–3322

Harnett P, Buck M, Beale P, Goldrick A, Allan S, Fitzharris B, De SP, Links M, Kalimi G, Davies T, Stuart-Harris R (2007) Phase II study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer: an Australian and New Zealand Gynaecological Oncology Group study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 17: 359–366

Kerbrat P, Lhomme C, Fervers B, Guastalla JP, Thomas L, Basuyau JP, Duvillard P, Cohen-Solal C, Dauplat J, Tournemaine N, Bachelot T, Ray I, Voog E (2001) Standards, options and recommendations for the initial management of patients with malignant ovarian epithelial tumors (abridged version). Gynecol Obstet Fertil 29: 733–742

Lhomme C, Ray-Coquard I, Guastalla JP, Bataillard A, Thomas L, Bonnier P, Dargent D, Dohollou N, Ganem G, Lefranc JP, Misset JL, Rixe O, Tchiknavorian X, Tournigand C, Villet R, Bachelot T, Kerbrat P, Fervers B, Basuyau JP, Cohen-Solal-Le Nir C, Morice P, Duvillard P, Voog E (2004) Clinical practice guidelines: standards, options and recommendations for first line medical treatment of patients with ovarian neoplasms (summary report). Bull Cancer 91: 609–620

Louvet C, Andre T, Lledo G, Hammel P, Bleiberg H, Bouleuc C, Gamelin E, Flesch M, Cvitkovic E, de GA (2002) Gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: final results of a GERCOR multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol 20: 1512–1518

Markman M, Blessing J, Rubin SC, Connor J, Hanjani P, Waggoner S (2006) Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) in platinum and paclitaxel-resistant ovarian and primary peritoneal cancers: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 101: 436–440

Markman M, Hoskins W (1992) Responses to salvage chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: a critical need for precise definitions of the treated population. J Clin Oncol 10: 513–514

Mavroudis D, Kourousis C, Kakolyris S, Agelaki S, Kalbakis K, Androulakis N, Souglakos J, Vardakis N, Samonis G, Georgoulias V (2000) Phase I study of the gemcitabine/oxaliplatin combination in patients with advanced solid tumors: a preliminary report. Semin Oncol 27: 25–30

Pectasides D, Pectasides M, Farmakis D, Aravantinos G, Nikolaou M, Koumpou M, Gaglia A, Kostopoulou V, Mylonakis N, Skarlos D (2004) Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in patients with cisplatin-refractory germ cell tumors: a phase II study. Ann Oncol 15: 493–497

Piccart MJ, Green JA, Lacave AJ, Reed N, Vergote I, Bedetti-Panici P, Bonetti A, Kristeller-Tome V, Fernandez CM, Curran D, van GM, Lacombe D, Pinel MC, Pecorelli S (2000) Oxaliplatin or paclitaxel in patients with platinum-pretreated advanced ovarian cancer: a randomized phase II study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gynecology Group. J Clin Oncol 18: 1193–1202

Raspagliesi F, Zanaboni F, Vecchione F, Hanozet F, Scollo P, Ditto A, Grijuela B, Fontanelli R, Solima E, Spatti G, Scibilia G, Kusamura S (2004) Gemcitabine combined with oxaliplatin (GEMOX) as second-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer refractory or resistant to platinum and taxane. Oncology 67: 376–381

Raymond E, Faivre S, Chaney S, Woynarowski J, Cvitkovic E (2002) Cellular and molecular pharmacology of oxaliplatin. Mol Cancer Ther 1: 227–235

Sehouli J, Stengel D, Oskay-Oezcelik G, Zeimet AG, Sommer H, Klare P, Stauch M, Paulenz A, Camara O, Keil E, Lichtenegger W (2008) Nonplatinum topotecan combinations vs topotecan alone for recurrent ovarian cancer: results of a phase III study of the North-Eastern German Society of Gynecological Oncology Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 26: 3176–3182

Steer CB, Chrystal K, Cheong KA, Galani E, Marx GM, Strickland AH, Yip D, Lofts F, Gallagher C, Thomas H, Harper PG (2006) Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin followed by paclitaxel and carboplatin as first line therapy for patients with suboptimally debulked, advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. A phase II trial of sequential doublets. The GO-First Study. Gynecol Oncol 103: 439–445

Theodore C, Bidault F, Bouvet-Forteau N, Abdelatif M, Fizazi K, di Palma M, Wibault P, de Crevoisier R, Laplanche A (2006) A phase II monocentric study of oxaliplatin in combination with gemcitabine (GEMOX) in patients with advanced/metastatic transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urothelial tract. Ann Oncol 17: 990–994

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, Van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada [see comments]. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 205–216

Vergote I, Rustin GJ, Eisenhauer EA, Kristensen GB, Pujade-Lauraine E, Parmar MK, Friedlander M, Jakobsen A, Vermorken JB (2000) Re: new guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors [ovarian cancer]. Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1534–1535

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Nathalie Le Fur for data management, M-Dominique Reynaud for editing assistance, and all investigators for inclusion of patients: C Alleaume, Saint–Brieuc; D Assouline, Grenoble; JC Barats, Colmar; B Chauffert, Dijon; G De Rauglaudre, Avignon; JP Désir, Clermont-Ferrand; PL Etienne, Saint-Brieuc; MH Filippi, Pontoise; G Freyer, Pierre-Bénite; F Guichard, Bordeaux; D Jaubert, Bordeaux; S Lavau-Denes, Limoges; D Lebrun-Jezekova, Reims; M Maigre, Saumur; E Malaurie, Créteil; MC Perrin, Bourg-en-Bresse; F Peyrade, Nice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented in part at the annual meeting of ASCO, Chicago, May 2003.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ray-Coquard, I., Weber, B., Cretin, J. et al. Gemcitabine-oxaliplatin combination for ovarian cancer resistant to taxane-platinum treatment: a phase II study from the GINECO group. Br J Cancer 100, 601–607 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604878

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604878

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hypersensitivity to oxaliplatin: clinical features and risk factors

BMC Pharmacology and Toxicology (2014)

-

Gemcitabine-oxaliplatin (GEMOX) as salvage treatment in pretreated epithelial ovarian cancer patients

Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2013)

-

Carboplatin and oxaliplatin in sequenced combination with bortezomib in ovarian tumour models

Journal of Ovarian Research (2013)

-

New emerging drugs targeting the genomic integrity and replication machinery in ovarian cancer

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2011)