Key Points

-

Highlights the use of checklists in dental hospitals to prevent wrong tooth extraction.

-

Describes other strategies used in dental hospitals to reduce the risk of wrong tooth extraction.

-

Examines the understanding of dental hospitals in England regarding 'Never Events'.

Abstract

Aim To identify the procedures in dental hospitals where a surgical safety checklist is used and in addition, in England, to identify the understanding of hospitals regarding patient safety incidents requiring reporting as Never Events to NHS England.

Method A self-completed questionnaire survey asking about the use of checklists was distributed to 16 dental hospitals associated with undergraduate dental schools in the UK and Ireland in the summer of 2015. For hospitals in England (10), additional questions regarding their understanding of incidents to be reported as Never Events were asked.

Results Thirteen hospitals replied (8 in England). All use a surgical safety checklist in an operating theatre setting. Ten use a surgical safety checklist in an outpatient setting for the extraction of teeth. There is variable use of checklists for other procedures. The majority of English hospitals thought that the reporting of a 'Never Event' was required following wrong tooth extraction in whatever setting it occurred, including general dental practice.

Conclusion Surgical safety checklists are increasingly used in dental hospitals, especially for oral surgery procedures. Beyond 'wrong tooth extraction', English dental hospitals have different understandings of what other oral and dental procedures require reporting as Never Events to NHS England.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2009, a landmark study reported on the effectiveness of using a surgical safety checklist in hospital theatres to reduce patient mortality and morbidity.1 The checklist was modelled on the airline industry's in-flight safety checklist. Shortly afterwards, the NHS requested the use of the WHO surgical safety checklist in hospital theatres throughout the country.2 Since then surgical safety checklists have been developed, introduced and studied for interventional procedures outside the theatre environment in many areas of healthcare. In dentistry this includes the use of a checklist to help prevent wrong tooth extraction.3 There is no information on the uptake of using checklists in dentistry in hospital environments, and for which procedures they are used. There is also little information on what other measures are used to reduce the risk of wrong tooth extraction.

In 2009, the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) in England identified a list of Never Events. These were defined as 'serious, largely preventable patient safety incidents that should not occur if the available preventive measures have been implemented by healthcare providers.'4 Should a Never Event occur then there was a requirement to report both locally and nationally to NHS organisations, with the proposal for subsequent publishing of summary data on events occurring. The aim was to encourage patient safety innovation and implementation by greater transparency and accountability when serious patient safety incidents occurred. NHS England has subsequently published modified guidance as to what patient safety incidents constitutes a 'Never Event', the most recent policy and framework being published in March 2015 for implementation on 1 April 2015.5,6,7,8,9,10,11

The aim of this survey was to identify for which dental procedures, checklists are currently in use in Dental Hospitals in the UK and Ireland, and what other measures are used to improve patient safety. It also aimed to identify the opinions of English dental hospitals as to which wrong site oral procedures they think requires reporting to NHS England as a Never Event.

Method

In the summer of 2015, a self-completed structured questionnaire (Appendix 1) was distributed to the clinical director (or equivalent) of 16 dental hospitals associated with undergraduate dental schools in the UK and Ireland asking about the use of checklists, and for the subset of ten dental hospitals in England additional questions were asked regarding Never Events. The closed sections of the questionnaire sought specific information on the use of checklists to prevent wrong site surgery in various clinical situations in their dental hospital. English dental hospitals were also asked about their understanding of what adverse incidents they felt met the criteria of reporting as Never Events to NHS England. The questionnaire also included an open section on what other approaches the hospitals used to reduce the risk of wrong tooth extraction. The outcomes of the questionnaire survey were presented to, and discussed by, attendees at the Association of Dental Hospitals Clinical Effectiveness meeting in Manchester in October 2015.

Results

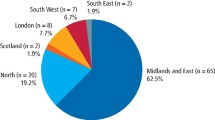

The questionnaire was completed and returned by 13 dental hospitals, eight of them in England. Three hospitals did not reply. Tables 1, 2 and 3 show the summated answers to the closed questions concerning the use of checklists. The open question 'please state any other approaches your hospital uses to reduce the risk of wrong tooth extraction' produced a variety of responses that can be grouped together in themes.

-

Notation and identification. One reply stated 'LL6 not FDI'. Three hospitals advised using words as well as dental nomenclature to make it unambiguous where necessary 'eg last standing molar tooth'. One hospital replied 'teeth to be extracted by students are also marked before extraction with a red wax marker'

-

Additional identification by patient. Two hospitals stated that as an additional check, the patient pointed to the tooth they thought would be extracted

-

Clarity during extraction procedure. One hospital stated they wrote the tooth details on a white board in the surgery. One hospital stated they wrote the tooth details on the patient's disposable bib

-

Training and human factors. Hospitals stated 'Induction training and peer review', 'Empowerment of all staff and students to speak up if they think an error may be made', 'Direct supervision of undergraduates', and 'Raised awareness of staff and students through communication'

-

Audit. One hospitals stated 'monthly audit of correct site surgery checklist in oral surgery'

-

Universal rule. One hospital stated 'We use a pre-needle time-out process for any procedure under LA or conscious sedation. We have a best practice storyboard for any extraction in a conscious or unconscious patient. We have posters demonstrating STOP before you block'.

Table 4 shows the summarised answers to the closed questions concerning understanding regarding the reporting of Never Events to NHS England.

Discussion

Wrong tooth extraction

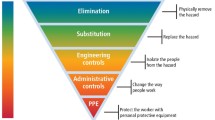

Wrong tooth extraction is an easily identifiable patient safety incident which results in a long term irrevocable change in the mouth. It has long been a source of distress for the affected patient, a source of anxiety for the presiding dentist and a source of clinical negligence payments for medical defence unions, insurance bodies and the NHS. We know that it continues to occur in dentistry but do not have accurate figures as to its frequency and volume.3,12,13 Studies have indicated risk factors that contribute to its occurrence including miscommunication between clinicians within and between clinics, having multiple teeth for extraction, partially erupted teeth mimicking third molars, teeth with gross decay and time pressures.14,15 In an attempt to reduce the risk of wrong tooth extraction occurring, strategies have been tried including educational programmes with various degrees of success.15,16 More recently checklists have been proposed and used in both a theatre and outpatient setting with some evidence of success in reducing the risk of wrong tooth extraction.3,17

Checklists

In 2009, the NPSA released a patient safety alert update following publication of a paper showing a reduction in morbidity and mortality when a surgical safety checklist was used in hospital operating theatres.2 The safety alert required NHS organisations to implement an adapted WHO Surgical Safety checklist for surgical procedures occurring in a 'sterile' environment, for example an operating theatre or procedure room. Hence, the finding that all hospitals surveyed are using a surgical safety checklist in a theatre environment might be expected.

Since 2009 there has been much interest in developing and using checklists in all areas of healthcare in an attempt to improve patient safety. In dentistry, experiences in the use of a surgical safety checklist to prevent wrong tooth extractions in dental hospital settings have been published.3 In addition, checklists have been proposed more recently for use in endodontic treatment, for dental implant placement and in the early identification of malignancy presenting as a temporomandibular disorder.18,19,20 This survey confirms the widespread use of checklists for oral surgical procedures in an out-patient setting in dental hospitals.

Checklists offer an important mechanism to improve patient safety however it is clear that on their own they may have no effect on reducing error if not used effectively. It is the culture of the environment into which they are introduced and used that can make the significant difference. When surgical safety checklists were mandated in hospitals in Ontario, Canada without cultural engagement, the effects were to result in no change in surgical mortality or complications.21 In a surgical environment, the checklist is an important mechanism for ensuring team communication occurs but it requires ownership and cultural acceptance by the team members to be most effective.22 The outcomes of the use of checklists or other patient safety initiatives were not measured in this survey, but it is heartening that so many hospitals are actively engaged in considering how patient safety can be improved.

Never Events

The first suggestion of identifying Never Events was made in the 2008 report 'High Quality Care for All'.23 The document reported that in some parts of the United States, clinical incidents that were serious and largely preventable had been designated Never Events and proposed that the NHS in England should do the same. In 2009, the NPSA published their first guidance on 'Never Events' and included wrong site surgery as one of the categories identified.4 The guidance explicitly stated that dentistry was excluded from the first phase of implementation and this was repeated in the subsequent guidance published in 2010.5 In 2011 and January 2012, further guidance was issued and dentistry or teeth were not mentioned.6,7

In October 2012, an updated Never Events policy framework was published.8 The framework clarified the 25 Never Events previously identified and in the section on 'specific never events definitions', gave guidance to the question of 'does wrong tooth extraction count as wrong site surgery?' It stated:

'The definition of the wrong site surgery never event relies on the procedure being undertaken being considered “surgical” by those involved. There is no easy definition of what is and what is not surgical, but there are some factors that providers and commissioners may wish to consider when looking at the incident:

-

Does the procedure involve sedation and/or general anaesthesia?

-

Does the procedure involve permanent alteration of the patient's physiology?

-

Does the patient consider the procedure surgical?

-

Will scarring result from the procedure (no matter how minor) or the procedure take time to heal?

If the answer to all or most of the above is yes, then it is likely the procedure is surgical and therefore could involve a wrong site surgery Never Event.

Therefore there are likely to be some tooth extraction procedures that are surgical and others that are not.'

In March 2015, a further updated Never Events policy and framework was published, applicable to all incidents that would occur on or after 1 April 2015.10 The full Never Events list 2015/16 is given in Fig. 1. The wrong site surgery definition was changed and for the first time the term 'wrong tooth' was explicitly included within the definition. In addition, the definition states that it includes 'interventions that are considered surgical but may be done outside of a surgical environment' as well as being applicable to 'all patients receiving NHS funded care'. The full definition of wrong site surgery is given in Fig. 2.

Never Events Policy and Framework, March 2015 – Never Events List 2015/1610

Never Events Policy and Framework, March 2015 – Wrong Site Surgery definition and settings10

At the same time, the 'Revised Never Events policy and framework – Frequently Asked Questions' was published which gave further specific guidance regarding wrong tooth extraction.11 It provided clarity in three specific circumstances:

-

It stated that a Never Event wrong tooth extraction did not apply to milk teeth

-

It confirmed that a wrong tooth extraction applied to the inadvertent removal of teeth (with dental caries) which would have been removed at a future appointment was a Never Event

-

It confirmed that even if the immediate re-implantation of a tooth removed in error was undertaken then it should still be reported as a Never Event.

One interpretation of the NHS England guidance in place since April 1 2015 indicates that wrong tooth extraction in all settings in patients receiving NHS funded care is applicable to all branches of dentistry. This is the interpretation that the majority of dental hospitals in England appear to have concluded. This interpretation includes wrong tooth extraction on NHS patients in general dental practice. Wrong site oral surgery, such as an apicectomy, is also interpreted as requiring reporting as a Never Event while there is no clear consensus view on whether wrong tooth root canal therapy or an inferior alveolar nerve block given to the wrong side would need reporting.

Wrong site surgery, including wrong tooth extraction, is clearly wrong and should be preventable. The concept of encouraging the implementation of patient safety mechanisms, such as use of a checklist, by reporting and publishing data when wrong site surgery occurs is understandable. Such transparency however is best suited to situations where clarity regarding what requires reporting is understood by all involved. The occurrences of Never Events may be reported by the media and it would seem unfair if an organisation which is attuned to the reporting requirements is penalised by bad publicity while other similar events elsewhere go unidentified. Currently, the requirement for dentists working in a primary care setting in England to report Never Events on patients treated under NHS funded care is unclear, but would seem to be covered by the guidance given in the current Never Events Policy and Framework.10,11 Understanding of what exactly constitutes a 'Never Event', however, also appears to show variations in interpretation in primary care dentistry.24

A recent paper exploring the risk of surgical Never Events in England put forward the conclusion that such events could be viewed as rare, random events in their distribution.25 It further noted that their most significant benefit is to provide a focus to review safety culture, policies and practice in the setting where they occur. With this in mind, dental hospitals appear to be embracing this function judging by their engagement and usage of checklists. How widely such aids to safety are used in dentistry outside of dental hospitals is unclear.

Dentistry has been slower than medicine in considering how patient safety can be improved.26 Further research, reflection and action is warranted. As part of that process, there would be benefit in further consideration by dentists, commissioners and system regulators about which wrong site surgery events in the oral cavity require reporting, by whom and by what mechanism, and how the resultant 'lessons learnt' can best be harnessed to maximise future patient benefit.

Conclusion

This survey shows that strategies to reduce the risk of wrong site surgery are increasingly being used in UK and Irish dental hospitals. Safer surgical checklists are used in all operating theatres for tooth extraction, and in the majority of hospitals in the out-patient setting for this purpose. Checklists are also widely used for oral surgery procedures, together with a range of other approaches to try and improve patient safety. The survey shows that the majority of English dental hospitals are of the understanding that a wrong tooth extraction on an NHS patient in whatever setting it occurs requires reporting as a Never Event to NHS England. There are fewer consensuses around what other oral procedures may require reporting as Never Events.

References

Haynes A B, Weiser T G, Berry W R et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 491–499.

National Patient Safety Agency. Patient Safety Alert update: WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. London: National Patient Safety Agency. 2009. Available online at https://doi.org/www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?EntryId45=59860 (accessed May 2016).

Saksena A, Pemberton M N, Shaw A, Dickson S, Ashley M P . Preventing wrong tooth extraction: experience in development and implementation of an outpatient safety checklist. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 357–62.

National Patient Safety Agency. Never Events framework 2009/10. London: National Patient Safety Agency, 2009.

National Patient Safety Agency. Never Events framework 2010/11. London: National Patient Safety Agency, 2010.

Department of Health. The Never Events list 2011/12. London: Department of Health, 2011.

Department of Health. The Never Events list 2012/13. London: Department of Health, 2012.

Department of Health. The Never Events policy framework: an update to the never events policy. London: Department of Health, 2012.

NHS. The Never Events list; 2013/14 update, London: NHS England, 2013.

NHS. Revised Never Events policy and framework. London: NHS England, 2015.

NHS. Revised Never Events policy and frameworkFrequently asked Questions. London: NHS England, 2015.

DDU. Rise in extraction error claims reports DDU. London: DDU, 2013. https://doi.org/www.theddu.com/press-centre/press-releases/rise-in-extraction-error-claims-reports-ddu (accessed September 2015).

Thusu S, Panesar S, Bedi R . Patient safety in dentistry – state of play as revealed by a national database of errors. Br Dent J 2012; 213: E3.

Peleg O, Givot N, Halamish-Shani T, Taicher S . Wrong tooth extraction: root cause analysis. Quintessence Int 2010; 41: 869–872.

Chang H H, Lee J J, Cheng S J et al. Effectiveness of an educational programme in reducing the incidence of wrong-site tooth extraction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004; 98: 288–294.

Lee J S, Curley A W . Prevention of wrong site tooth extraction: clinical guidelines. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 65: 1793–1799.

Perea-Perez B, Santiago-Saez A, Garcia-Marin F, Labajo Gonzalez E . Proposal for a 'surgical checklist' for ambulatory oral surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 40: 949–954.

DiazFloresGarcia V, Perea-Perez B, Labajo-Gonzales E, Santiago-Saez A, Cisneros-Cabello R. Proposal of a 'Checklist' for endodontic treatment. J Clin Exp Dent 2014; 6: e104–e109.

Christman A, Schrader S, John V et al. Designing a safety checklist for dental implant placement. A Delphi study. JADA; 145: 131–140.

Beddis H P, Davies S J, Budenburg A, Horner K, Pemberton M N . Temporomandibular disorders, trismus and malignancy: development of a checklist to improve patient safety. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 351–355.

Urbach D R, Govindarajan A, Saskin R, Wilton A S, Baxter N N . Introduction of surgical safety checklists in Ontario, Canada. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1029–1038.

Leape L L . The checklist conundrum. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1063–1064.

High Quality Care For All-NHS Next Stage Final Review Report. London: Department of Health, June 2008.

Bailey E . Contemporary views of dental practitioners on patient safety. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 535–540.

Moppett I K, Moppett S H . Surgical caseload and the risk of surgical never events in England. Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 17–30.

Pemberton MN . Developing patient safety in dentistry. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 335–337.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges the time taken by colleagues in the Association of Dental Hospitals in completing and returning the questionnaires.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pemberton, M. Surgical safety checklists and understanding of Never Events, in UK and Irish dental hospitals. Br Dent J 220, 585–589 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.414

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.414

This article is cited by

-

Surgical safety checklists for dental implant surgeries—a scoping review

Clinical Oral Investigations (2022)

-

Patient safety: Never say never

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Patient safety: reducing the risk of wrong tooth extraction

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

The use and understanding of dental notation systems in UK and Irish dental hospitals

British Dental Journal (2017)