Key Points

-

Highlights the anatomical link between the dental pulp and the periodontal ligament.

-

Presents an update on the classification of periodontal-endodontic lesions.

-

Discusses the treatment options for periodontal-endodontic lesions.

Abstract

This paper reviews the classification of periodontal-endodontic lesions and considers the pathways through which inflammatory lesions or bacteria may communicate between the pulp and the periodontium. Such communications have previously underpinned the classification of periodontal-endodontic lesions but a more up-to-date approach is to focus specifically on those lesions that originate concurrently as pulpal infection (and necrosis) and periodontal disease on the affected teeth. In doing so, both conventional periodontal and endodontic treatments are indicated for the affected teeth, although more complex management strategies may occasionally be indicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The periodontal-endodontic interface has provided significant challenges for clinicians over several decades. The diagnosis and management of the so-called 'periodontal-endodontic' group of lesions is based upon the known continuum between the otherwise anatomically distinct environments of the dental pulp and the periodontal ligament. This continuum, which is dependent upon a series of anatomical communications, has of course, not changed over time although our knowledge and understanding of the impacts of pulpal disease on the periodontium and chronic periodontitis on the pulp most certainly have. It is important to have a thorough understanding of the basic anatomy, the aetiology and the development of periodontal-endodontic lesions (PEL) if they are to be managed successfully and for both clinicians and patients to be able to confidently base decisions regarding appropriate treatment options and long-term prognoses for affected teeth.

Classification

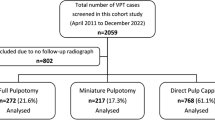

While there have been a number of attempts to classify PEL1,2,3,4 the most quoted classification remains that of Simon et al.5 which was first published in 1972. This classification is based on the observation that most PELs will have originated in either the pulp or the periodontium and classifies the initial lesions as being primary periodontal or primary endodontic lesions respectively. As the inflammation spreads from the original site the lesions develop to effect secondary involvement of the adjoining anatomical site, for example, into a primary endodontic and secondary periodontal lesion. When a PEL develops simultaneously as periapical pathology and chronic (or aggressive) periodontitis then it is classified as a 'true', combined periodontal-endodontic lesion. While this classification has certainly stood the test of time it is often difficult to confidently compartmentalise PELs into one of the five categories (Fig. 1). This classification identifies pulpal/periapical infection and periodontal infections as primary, separate entities that may spread to cause secondary infections. Where does a primary endodontic lesion end and a primary endodontic with secondary periodontal involvement begin? It might also be considered unnecessary and confusing to include the singular, primary lesions in such a classification. This classification was challenged as being primarily 'academic' and of little help to the clinician who needs to know the precise clinical need of a tooth (teeth or patient) before making an informed decision as to the appropriate treatment(s) to offer.6

The 'True', combined lesion is the only lesion that is considered in the more recent classification of Abbott and Castro Salgado9 who then make the distinction between endodontic and periodontal lesions that do, or do not communicate

Interestingly, the American Academy of Periodontology's (AAP) 1989 classification of gingival and periodontal diseases did not recognise the association between periodontal and endodontic disease and it was only in 1999 that the AAP workshop included the simple term 'periodontitis associated with endodontic lesions – a combined periodontal-endodontic lesion'.7,8 The consensus opinion was to propose a classification that was not based on such extensive 'compartmentalisation' of the infections and a more recent classification has also adopted this approach.9 The classification of Abbott and Salgado focuses specifically on only those lesions that are associated with both periodontal and endodontic diseases that affect a tooth or teeth simultaneously with the principal distinction being whether or not the lesions communicate with each other (Figs 2 and 3). Thus there are only two possible categories which, following clinical and radiographic examinations facilitate the diagnosis and therefore the management of the lesion:

-

Concurrent endodontic and periodontal disease without communication (Fig. 2)

-

Concurrent endodontic and periodontal disease with communication (Fig. 3).9

47 is also non-vital and has extensive apical pathology although the apical and periodontal lesions remain separate and do not communicate9

43, 31, 32, 37 and 38 are all non-vital and demonstrate apical pathology as well as periodontal involvement. The lesions are communicating9 and as such, will compromise the prognosis for the involved teeth

The former suggests a tooth that happens to be affected by both pulpal and periodontal disease at the same time and which requires treatments targeting both causes; the latter can be considered a lesion of singular aetiology (a 'true' periodontal-endodontic lesion) and for which a considered judgement of prognosis should be made before embarking on a more intensive treatment regimen.

Anatomical considerations

Many of the classifications and the management strategies for PELs have been based upon the well-established anatomical communications between the pulp and the periodontium. It is pertinent to briefly review these although the role of many of these communicating pathways may not be as crucial as once was believed.

Around 27% of teeth demonstrate lateral or accessory canals. These can be found along most parts of the root structure with the majority (17%) being found in the apical third, around 9% in the middle third and 2% in the gingival third of the root.10 The furcation region of molars has the highest prevalence of accessory canals with approximately 25% of molars showing such features.11 It would appear, however, that only around 10% of molars have furcation canals that communicate directly with the pulp chamber12 whereas up to 60% have furcation canals that communicate with the most coronal aspect of the root canal.13 The potential relevance of these canals is that they effect anastomoses between the vast networks of capillary beds in the pulp with the vascular supply to the periodontal ligament, and in doing so provide the opportunity for the spread of an inflammatory lesion between the structures.

Another communication channel between the pulp and the periodontium is through patent dentinal tubules that may be exposed at the cement-enamel junction due to absence of cementum, or on a root surface of a periodontally-involved tooth that has been subjected to root surface instrumentation. Unlike the accessory canals that transmit blood vessels, however, the dentinal tubules are occupied by the processes of the odontoblasts and dentinal fluid, which may underpin the symptoms of dentine sensitivity.14 The role of dentinal tubules in the aetiology of PELs is not necessarily associated with spread of inflammation but with the bacterial invasion and spread of the microflora either from the root canal to the periodontal ligament or from a periodontal pocket in the opposite direction.15

The classification given in the previous section9 is based on an inflammatory continuum that occurs only when a progressing periodontal lesion and pulpal infection extend to, and beyond the apex of the tooth. This concurs with previous histological evidence that suggests that pulpal involvement from a PEL will only develop once the periodontal lesion extends to, and beyond the apex of the tooth.16

Consequences of bacterial invasion

Both endodontic and periodontal infections derive their microflora from the multitude of organisms that reside in the oral cavity and similar anaerobic conditions favour growth of anaerobes both in the infected pulp and periodontal pockets.17 This, together with the numerous anatomical communications between the pulp and the periodontium may at least partly explain why these distinct environments have similar microbiological profiles.18,19,20,21 The dentinal tubules adjacent to both the pulp and the diseased periodontium may also be subject to bacterial invasion from an adherent biofilm and even if the contained organisms are unable to facilitate free passage from one surface to the other, they may still provide a potent reservoir of persistent infection in a necrotic pulp or an infected periodontal pocket.22,23,24 The invasion of root dentine by bacteria, however, does not necessarily imply that an inflammatory periodontal lesion will initiate irreversible pathological change in the pulp. Whether or not the odontoblastic processes form a protective barrier to bacterial exchange is debatable25 and although there is histopathological evidence of pulpal change in caries-free, periodontally-affected teeth, these are likely to be limited to fibrosis, dystrophic calcifications and reduced vascularity.14 Indeed, it has been suggested that irreversible inflammatory change of the pulp only occurs once the apical vessels have become involved16 and this latter observation would further corroborate the adoption of a classification that distinguishes simply between PELs that do or don't communicate in the vicinity of the apex of a tooth.9 These observations have further been corroborated by the findings of a classic animal study that exposed root surfaces to experimental periodontitis and found that while there were concurrent pathological changes in the pulp, these were mainly limited to mild inflammation and secondary dentine formation, again suggesting the pulp has an inherent capacity to protect itself. Failure to detect any accessory root canals implied that the bacterial challenge would, most likely, have occurred through patent dentinal tubules.26 Furthermore, when extensive root instrumentation that removed most of the cementum was undertaken and followed by further plaque accumulation there appeared to be little, if any, additional pulpal pathology.26

Although the communication and passage of inflammation between the pulp and the periodontal ligament is possible, it is when the pulp has necrosed and an apical infection has developed that the periodontium may be further compromised. This relationship between established periapical pathology and periodontal disease has been evaluated in several studies that have suggested that teeth with necrotic pulps and apical pathology can both exacerbate periodontal disease and compromise healing following non-surgical periodontal treatment.27,28,29 For example, a cohort study of patients with endodontically-involved, single rooted teeth demonstrated an association between periapical pathology and vertical periodontal bone lesions. It was concluded that intrapulpal infection, evident as periapical radiolucency, may promote bone loss and be considered a risk factor for periodontal progression.29

The diagnosis of periodontal-endodontic lesions

The diagnosis of pulpal/periapical or periodontal disease as distinct entities is based on a thorough clinical examination utilising pulp sensibility tests, percussion, transillumination, test cavities, probing pocket depths, an assessment of mobility, and identification of bleeding and, or suppurating pockets.9,30 Occasionally, a localised problem such as an extensive periapical lesion that tracks coronally through an otherwise healthy periodontal ligament may present as a narrow sinus tract and mimic periodontal disease. This might be classified as a primary endodontic lesion with secondary periodontal involvement5 although this would not be included in the definition of a concurrent PEL suggested earlier in this paper.9 Consequently, the management would simply involve root canal therapy of the affected tooth.

Concurrent PELs will usually affect a single tooth although multiple affected teeth may present in a patient where there has been widespread dental neglect (Fig. 3). The teeth involved may have extensive carious lesions and large restorations and will consequently fail to respond to sensibility tests. There will be increased, wide-based probing depths with bleeding or suppuration from the pockets and the tooth may be tender to percussion in the presence of an acute apical or periodontal abscess (or both).9 Panoramic oral radiographs will reveal the extent, morphology and the severity of the periodontal bone loss and supplementary, conventional or digital periapical films may be exposed for those teeth which, on the basis of clinical findings and the panoramic film, appear to have apical pathology.31 A periapical film will provide the required definition to ascertain the apical extent of the periodontal lesion (the point at which the periodontal membrane space assumes normal width) and the coronal margin of a periapical lesion and thus help in identifying whether or not the separate periodontal and pulpal inflammatory lesions communicate. Periodontal-endodontic lesions may be associated with teeth having previously been root filled and the limitations of conventional (two-dimensional) periapical radiographs must be recognised as they may not correlate with the three-dimensional quality of a root filling.32 An apparently well-condensed and well-adapted root filling associated with a PEL may need to be retreated if the long-term outcome for the tooth is to be assured (Fig. 4). Furthermore, when conventional, plain films fail to provide sufficient diagnostic information limited-volume, high-resolution cone beam computed tomography may be justifiable for assessing and treatment planning periodontal-endodontic lesions.33

The radiograph taken along the buccal-palatal axis suggests that the root fillings in both roots appear to be adequate

4b When the tube and film are positioned so that the primary beam is in the mesial-distal axis it becomes clear that the root fillings are inadequately condensed and not achieving apical seal

The treatment of concurrent periodontal-endodontic lesions

While this section will consider the management of the concurrent PEL, it is important to recall that infected or necrotic pulps (or indeed lesions associated with root perforations or failing root canal therapy) may lead to a narrow sinus tract that mimics a periodontal pocket. Because the aetiology of such lesions is pulpal in origin, the indicated treatment is root canal therapy (or replacement of a root filling(s) where a previous treatment appears to have failed and the infection has persisted) or, where indicated, an attempted repair of a perforated root. Long-term follow-up and monitoring is required to assess healing and to assess whether apical surgery or perhaps extraction may be indicated should the infection persist.

Similarly, if a vital tooth affected by periodontal disease develops pulpal symptoms then periodontal treatment is the priority intervention, again with long-term follow-up to ensure that what is likely to be only a mild inflammatory reaction of the pulp (which may exacerbate after root instrumentation) resolves as the vital pulp resists the spread of inflammation from the periodontal lesion.

Thus concurrent periodontal-endodontic infections that don't communicate should be managed by root canal therapy to eliminate the source of pulpal infection and instrumentation of root surfaces that are then less likely to communicate residual infection through dentinal tubules or accessory canals.9

Before embarking on treatment of lesions that communicate, however, it would be pragmatic to ascertain the patient's perspective and views on treatment of the tooth, which may carry no guarantee of long-term success; and particularly so where multiple teeth may be affected and considered to be unrestorable, and where extraction would be the preferred option. While there is evidence that root canal treatment alone is a cost-effective approach compared to extraction and restoration of the space,34 there are no data available that establish the cost-effectiveness of an approach that may be expensive in terms of both time and money and particularly so when advanced management strategies may be indicated.

The initial objective for those PELs that communicate should be to disinfect the entirety of the affected site as quickly and effectively as possible and by engaging a strategy of shared care between dentist and hygienist. The best approach would be to manage the endodontic and periodontal infections 'aggressively' and simultaneously: initially thorough root instrumentation of the periodontal site and application of local delivery antimicrobials; together with removal of the necrotic pulp, initial cleaning and shaping of the root canal with liberal irrigation and application of endodontic medicaments such as non-setting calcium hydroxide, Ledermix or TreVitaMix. Placement of the definitive root filling should be delayed until the healing response to periodontal management can be assessed after three to six months (Fig. 5).

The initial phase of periodontal treatment and root canal therapy has stabilised the tooth, which is symptom free. Further treatment options include periodontal surgery with guided tissue regeneration or root resection. Note the sealant extruded from the mesiobuccal canal has migrated along the communication between the periodontal and endodontic lesions.

At this point it is worth noting that the channels of communication between the pulp and the periodontium, the accessory canals, dentinal tubules and the apical foramen, which have thus far been a hindrance, may now work in favour of the clinician. Although there is as yet no evidence to suggest that antimicrobials delivered locally to periodontal pockets can influence bacteria that may have invaded root dentine there is some evidence to suggest that bacterial inhibition can occur after penetration through dentine of antimicrobials that have been placed in the pulp. This effect also seems to occur irrespective of whether or not the cementum layer has been removed through root instrumentation. It is conceivable, therefore, that medicaments placed in the pulp and then renewed on a regular basis will contribute to disruption of root surface microorganisms and healing of the periodontal site.35

From the periodontal viewpoint, teeth with extensive PELs may require more complex management strategies to improve the likelihood of long-term success. For example, in cases where only one root of a molar appears to be affected then there is an option of root resection of an upper molar or hemi-section of a lower molar following placement of the definitive root filling. In such cases, the remaining root(s) should have sufficient periodontal support to maintain the tooth in function and the procedures are usually limited to cases where the objective is to maintain an intact dental arch, function or a key tooth that may ultimately be helpful as an abutment for a fixed or removable prosthesis.

Similarly, when a definitive root filling has been placed, symptoms and signs of infection have resolved, but a furcation lesion or a deep vertical defect persists, then an exploratory surgical procedure may reveal a periodontal morphology that is conducive to a periodontal regenerative procedure.

Prognosis

The long-term, successful prognosis for teeth with periodontal-endodontic lesions depends on a number of crucial and key factors including the severity and extent of the initial periodontal and periapical infections, correct treatment planning and decision-making, the skill and experience of the clinician(s) and the motivation of the patient, particularly with long-term periodontal care.

It would seem logical to suggest that the prognosis for any tooth affected by lesions that communicate as a single, extensive infection must be guarded at best as the outcome ultimately depends on both successful periodontal and endodontic management. There are, as yet, few data available on the long-term outcomes for teeth affected by PELs. One study, however, identified teeth as having hopeless prognoses as a consequence of PELs with attachment loss to their apices.36 The teeth were treated endodontically and periodontally with the latter including a surgical approach with periodontal regenerative procedures. After five years, 23 out of 25 teeth were maintained in situ in good health and function and 83% were free from any complications during the review period. While one has to be careful not to conclude that all teeth with hopeless prognoses should be managed this way, these data do demonstrate the remarkable healing potential of the perio-pulpal complex.36

The considerable data on the ten-year outcomes of teeth having been root resected are also favourable and show tooth retention rates in the region of 60-100%.37,38,39,40,41 But again, it must be emphasised that such outcomes are usually achieved with extremely motivated patients who have been treated by experienced clinicians and under ideal conditions.

Conclusion

Periodontal-endodontic lesions present on teeth that are affected concurrently by periodontal and pulpal infections, which lead to pulpal necrosis and attachment loss respectively. These lesions may or may not communicate in the vicinity of the apex of the tooth. Both endodontic and periodontal treatments are indicated in the first instance, although where lesions are more advanced, the long-term prognosis may be improved by careful treatment planning and scheduling more complex management strategies such as root resection and periodontal regeneration.

References

Gargiulo A V . Endodontic-periodontic interrelationships. Diagnosis and treatment. Dent Clin North Am 1984; 28: 767–781.

Weine F . Endodontic-periodontic problems. In Weine F (ed) Endodontic therapy. 4th ed. pp 550–581. St Louis: CV Mosby Co, 1989.

Guldener P H . The relationship between periodontal and pulpal disease. Int Endod J 1985; 18: 41–54.

Torabinejad M, Trope M . Endodontic and periodontal interrelationships. In Walton R E, Torabinejad M (eds) Principles and practice of endodontics. 2nd ed. pp 442–456. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 2002.

Simon J H, Glick D.H, Frank A L . The relationship of endodontic-periodontal lesions. J Periodontol 1972; 43: 202–208.

Chapple I L, Lumley P J . The periodontal-endodontic interface. Dent Update 1999; 26: 331–341.

The American Academy of Periodontology. Proceedings of the World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics, 1989, I/23–I/24.

Armitage G C . development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol 1999; 4: 1–6.

Abbott P V, Castro Salgado J . Strategies for the endodontic management of concurrent endodontic and periodontal lesions. Aust Dent J 2009; 54: 70–85.

De Deus Q D . Frequency, location and direction of the lateral, secondary and accessory canal. J Endod 1975; 1: 361–366.

Gutmann J L . Prevalence, location and patency of accessory canals in the furcation region of permanent molars. J Periodontol 1978; 49: 21–26.

Vertucci F J, Williams R G . Furcation canals in the human mandibular first molar. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1974; 38: 308–314.

Lowman J V, Burke R S, Pelleu G B . Patent accessory canals: Incidence in molar furcation region. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1973; 36: 580–584.

Pack A R . Periodontal considerations in endo/perio lesions. Aust Dent J 2001; 27: 39–42.

Love R M, Jenkinson H F . Invasion of dentinal tubules by oral bacteria. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2002; 13: 171–183.

Langeland K, Rodrigues H, Dowden W . Periodontal disease, bacteria, and pulpal histopathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1974; 37: 257–270.

Zender M, Gold S I, Hasselgren G . Pathological interactions in pulpal and periodontal tissues. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29: 663–671.

Kobayashi T, Hayashi A, Yoshikawa R, Okuda A, Hara K . The microbial flora from root canals and periodontal pockets of non-vital teeth with advanced periodontitis. Int Endod J 1990; 23: 100–106.

Sundqvist G . Associations between microbial species in dental root canal infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1992; 7: 257–262.

Kurihara H, Kobayashi Y, Francisco L A, Isoshima O, Nagai A, Murayama Y . A microbiological and immunological study of endodontic-periodontal lesions. J Endod 1995; 21: 617–621.

Kipioti A, Nakou M, Legakis N, Mitsis F . Microbiological findings of infected root canals and adjacent periodontal pockets in teeth with advanced periodontitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1984; 58: 213–220.

Ando N, Hoshino E . Predominant obligate anaerobes invading the deep layers of root canal dentine. Int Endodont J 1990; 23: 20–27.

Adriaens P A, De Boever J A, Loesche W J . bacterial invasion in root cementum and radicular dentine of periodontally diseased teeth in humans. J Periodontol 1987; 59: 222–230.

Giuliana G, Ammatuna P, Pizzo G, Capone F, D'Angelo M . Occurrence of invading bacteria in radicular dentin of periodontally diseased teeth: microbiological findings. J Clin Periodontol 1997; 24: 478–485.

Adriaens P A, De Boever J A, Loesche W J . Bacterial invasion in root cementum and radicular dentine of periodontally diseased teeth in humans. A reservoir of periodontopathic bacteria. J Periodontol 1988; 59: 222–230.

Bergenholtz G, Lindhe J . Effect of experimentally-induced marginal periodontitis and periodontal scaling on the dental pulp. J Clin Periodontol 1978; 5: 59–73.

Ehnevid H, Jansson L, Lindskog S, Blomlöff L . Periodontal healing in teeth with periapical lesions. A clinical retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol 1993; 20: 254–258.

Ehnevid H, Jansson L, Lindskog S, Blomlöff L . Periodontal healing in teeth with periapical lesions. A clinical retrospective study. J Periodontol 1993; 64: 1199–1204.

Jansson L, Ehnevid H, Lindskog S, Blomlöff L . Relationship between periapical and periodontal status. A clinical retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol 1993; 20: 117–1123.

Rotstein I, Simon J H S . Diagnosis, prognosis and decision-making in the treatment of combined periodontal-endodontic lesions. Periodontol 2000 2004; 34: 165–203.

Corbett E F, Ho D K L, Lai S M . Radiographs in periodontal disease diagnosis and management. Aust Dent J 2009; 54: S27–S43.

Kersten H W, Wesselink P R, Thoden van Velzen S K . The diagnostic reliability of the buccal radiograph after root canal filling. Int Endod J 1987; 20: 20–24.

Patel S, Saunders W . Radiographs in endodontics. In Horner K, Eaton K A. (eds) Selection criteria for dental radiography. 3rd ed. pp 83–96. London: FGDP (UK), 2013.

Pennington M W, Vernazza C R, Shackley P, Armstrong N T, Whitworth J M, Steele J G . Evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of root canal treatment using conventional approaches versus replacement with an implant. Int Endod J 2009; 42: 874–883.

Zaruba M, Rechenberg D K, Thurnheer T, Attin T, Schmidlin P R . Endodontic drug delivery for root surface disinfection – a laboratory investigation. (Personal communication).

Cortellini P, Stalpers G, Mollo A, Tonetti M S . Periodontal regeneration versus extraction and prosthetic replacement of teeth severely compromised by attachment loss to the apex: 5-year results of an ongoing randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 2011; 38: 915–924.

Langer B, Stein S D, Wagenberg B E . An evaluation of root resections. A ten-year study. J Periodontol 1981; 52: 719–722.

Bűhler H . Evaluation of root-resected teeth. Results after 10 years. J Periodontol 1988; 59: 805–810.

Carnavale G, Pontoriero R, Di Febo G . Long-term effects of root-resective therapy in furcation-involved molars. A 10-year longitudinal study. J Clin Periodontol 1998; 25: 209–2014.

Blomlöff L, Jansson L, Appelgren R, Lindskog S . Prognosis and mortality of root-resected molars. Int J Periodont Rest Dent 1997; 17: 190–201.

Carnavale G, Di Febo G, Tonelli M P, Marin C, Fuzzi M . A retrospective analysis of the periodontal-prosthetic treatment of molars with interradicular lesions. Int J Periodont Rest Dent 1991; 11: 189–205.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heasman, P. An endodontic conundrum: the association between pulpal infection and periodontal disease. Br Dent J 216, 275–279 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.199

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.199

This article is cited by

-

Relationship between the difference in electric pulp test values and the diagnostic type of pulpitis

BMC Oral Health (2021)

-

What BDJ readers were reading spring 2014

British Dental Journal (2014)