Key Points

-

Dental implants are a more conservative long term option than long span bridges.

-

Placement of dental implants serves to preserve bone.

-

Dental implants can provide posterior support. Removable partials dentures do not provide posterior support long term.

-

Dental implants are resistant to disease.

Key Points

Implants

-

1

Rationale for dental implants

-

2

Treatment planning of implants in posterior quadrants

-

3

Treatment planning of implants in the aesthetic zone

-

4

Surgical guidelines for dental implant placement

-

5

Immediate implant placement: treatment planning and surgical steps for successful outcomes

-

6

Treatment planning of the edentulous maxilla

-

7

Treatment planning of the edentulous mandible

-

8

Impressions techniques for implant dentistry

-

9

Screw versus cemented implant supported restorations

-

10

Designing abutments for cement retained implant supported restorations

-

11

Connecting implants to teeth

-

12

Transitioning a patient from teeth to implants

-

13

The role of orthodontics in implant dentistry

-

14

Interdisciplinary approach to implant dentistry

-

15

Factors that affect individual tooth prognosis and choices in contemporary treatment planning

-

16

Maintenance and failures

Abstract

The clinical replacement of lost natural teeth by osseointegrated implants has represented one of the most significant advances in restorative dentistry. Two decades ago, a majority of dentists were sceptical about implants and rejected them entirely. Today it is rare to find a practitioner who does not work with dental implants or who is not actively participating in one of the many seminars or courses offered by universities, professional societies and implant manufacturers.1

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Compared to all other dental disciplines, implant dentistry has enjoyed far more innovation and progressive development in recent years. Indeed in this regard are the developments of new implant systems, the propagation of new and improved diagnostic procedures and the introduction of novel surgical techniques. Technical procedures have also advanced from the introduction of state of the art CADCAM technology to improve prosthodontic precision of fit and allow restoration of implants in non-ideal positions.

The goal of modern implant dentistry is no longer represented solely by successful osseointegration. Today clinicians can prescribe the use of implants with the knowledge and confidence that they will predictably integrate into the jaw bone. In order to claim success the definitive restorations must restore the patient to normal contour, function, aesthetics, speech and health.

The clinical success of implant therapy in edentulous and partially edentulous patients is well documented2,3 and many clinicians realise the benefits of adopting implant therapy in their practices. Implant therapy offers many advantages over conventional fixed or removable treatment options and in many cases is the treatment of choice. However, many clinicians still do not use implant therapy and choose instead to prepare teeth for fixed partial dentures. To obtain optimal aesthetic results with fixed partial dentures, a significant reduction in the amount of tooth structure is necessary, occasionally predisposing to endodontic, periodontal and structural sequelae.

The increased need and advantages of implant supported and retained restorations are a result of many factors which can be divided into four categories:

-

1

Preservation of tooth structure

-

2

Preservation of bone

-

3

Provision of additional support

-

4

Resistance to disease.

Each of the above points will be addressed in this article.

Preservation of tooth structure

Fixed partial dentures have been considered the standard of care prior to the advent of implant therapy. As mentioned previously, a significant amount of tooth structure needs to be removed for an aesthetic outcome (Figs 1 and 2). This removal of tooth structure compromises the longevity of the tooth and can in some instances result in endodontic, periodontal and mechanical complications. The long term survival of fixed partial dentures has been reported to be 87% at 10 years and 69% at 15 years.4 Factors that predisposed to failure included non-vital anterior abutments and pier abutments. Likewise, teeth that are pulp capped are at high risk for requiring endodontic therapy and make poor choices for abutment teeth, as any subsequent endodontic treatment would remove additional tooth structure necessary for long term stability of an FPD. Studies surveying survival of single tooth implant supported restorations are not so abundant. One study5 compiled all available studies from 1981 to 1997 published in English. It reported types of complications related to types of prosthesis, arch, time, implant length and bone quality. In comparison to other prosthetic designs implant single crowns had the lowest failure rate at 2.7%. They also reported that most failures occurred within the first year and implant loss was significantly lower in the subsequent second and third years. This tells the clinician that once the restoration has passed the first year in service it is likely to survive a considerable length of time. Naert et al.6 also reported a cumulative success rate of 96.5% over an 11 year period and there are numerous other studies alluding to the longevity of single unit implant restorations.7,8,9 Single tooth implant survival has been demonstrated to be the most predictable method of tooth replacement. There have also been no reports of loss of adjacent teeth when single tooth implant restorations have been undertaken; this is vastly different to when treatment is rendered with a FPD which may require the span to be extended further, additional endodontic and periodontal treatment thus further compromising the long term stability of the prosthesis.

Post operative situation following delivery of prostheses in Fig. 1

The multiple advantages of single tooth implant therapy over fixed partial dentures for replacing missing teeth should indicate to the practitioner that it is the treatment of choice. This is particularly relevant when the adjacent teeth are unprepared and exhibit large pulp chambers which may be compromised with more conventional treatments. If the adjacent teeth are extensively restored the practitioner must undertake a risk assessment analysis anticipating potential failure and what the cost of the failure would be both biologically and financially.

Preservation of bone

There is a close relationship between the tooth and the alveolar process throughout life. Every time the function of bone is modified a change occurs in the internal architecture and external configuration.10 Bone requires stimulation to maintain its form and density. When a tooth is lost, the lack of stimulation to the residual bone causes a decrease in trabeculae and bone density in the area, with loss in height and width of bone11 (Figs 3,4,5). A 25 year study of edentulous patients demonstrated continued bone loss during this time span. A four fold greater loss was demonstrated in the maxilla than in the mandible.12 In the edentulous patient bone tends to resorb upwards and medially in the maxilla and downwards and laterally in the mandible. This often results in a jaw size discrepancy which tends more toward a class 3 skeletal relationship. To respect this natural disproportion, teeth must be aligned differently with the maxillary molars being more facially positioned and the mandibular molars being more lingually positioned (Figs 6,7). The literature concludes that teeth are required to maintain bone and with loss of teeth, bone is no longer stimulated. The question now becomes do complete or partial dentures provide sufficient stimulation of the ridges to maintain the bone levels? Based on the results of the above study this cannot be confirmed. A partial or complete denture does not maintain the bone and in fact may accelerate bone loss if the prosthesis is ill-fitting. These types of patients are often not told about the anatomical consequences of bone loss when their teeth are extracted, they are not informed that bone loss will continue to occur over a period of time and this continual resorptive process has many consequences. Continued bone loss decreases the surface area available for prosthesis support, eliminates favourable anatomy for retention and results in unfavourable denture bearing areas. Loss of lateral stability and retention increases prosthesis movement resulting in increased friction and mucosal irritation. The bone loss can be so severe that even if the patient desires implant therapy there may not be sufficient bone for implant placement and aggressive adjunctive surgical procedures would be required such as grafting from the iliac crest (Figs 8-9). Together with the bone loss are associated soft tissue changes which can significantly affect the overall aesthetics. Facial changes that occur as a result of ageing are accelerated with the loss of teeth. The loss of facial support and reduction in vertical dimension gives us the classic appearance of the denture patient who presents with a decreased nose to chin distance, deepening of the labiomental fold and thinning of the vermillion border of the lips. These changes have serious aesthetic repercussions for the patient. These biological changes can be avoided by placement of implants which will stimulate the bone and avoid subsequent resorption (Figs 10-11).

Clinical situation of Fig. 4, illustrating bone resorption

Edentulous patients are unaware of the consequences of tooth loss; many of them wear the same prosthesis for many years and do not return for evaluation. Patients should be made aware and informed of the preventive nature of dental implants. Dental implants can prevent bone loss and maintain the hard and soft tissue so compromises in function and aesthetics need not occur.12,13,14

Provision of additional support

Additional support can be provided with the use of dental implants. This additional support translates to improved masticatory performance. A patient who grinds or clenches can exert up to 1000 psi of force. The maximum occlusal force in an edentulous patient can be reduced to 50 psi. The literature also states that the longer a patient is edentulous the less force they are able to generate.13 There are many studies that point towards complete denture patients having impaired masticatory efficiency.14,15 This compromised state can affect a patient's overall health and indeed may result in patients suffering from gastro-intestinal and other systemic disturbances. Restoring a patient's stomatognathic system to a more normal function may enhance their masticatory performance and improve the quality of their lives.

Transitioning a patient from a complete denture to an implant supported fixed prosthesis results in a dramatic increase in maximal bite force. Complete denture patients are unable to exert equivalent forces due to the limitation of pain in the soft tissue arising as a result of increased pressure on the denture bearing areas. The patient with an implant supported fixed prosthesis can exert a similar force to that of a patient with fixed restorations on teeth. The improved stability and retention of an implant supported prosthesis is a vast improvement on soft tissue supported dentures.

Patients also present clinically with one or more signs of lack of posterior support. These signs may include but are not limited to wear, splaying and fremitus of the anterior teeth. Traditionally these restorative problems were addressed by splinting the anterior teeth and provision of a tooth and mucosa supported Kennedy Class 1, removable partial denture. The function of the partial denture was to provide increased chewing surface and re-establish posterior support. Monteith16 reported that there is a marked difference in the viscoelastic response to loading of teeth and mucosa. The marked disparity between the 500 micron resilience of the residual ridge tissues and the 20 microns of teeth brings to light the questionable nature of providing posterior support with removable partial dentures. It is the authors' opinion that tooth and mucosa supported partial dentures cannot re-establish posterior support in the long term due to the resilient and like effect of the mucosa.

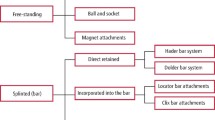

One additional advantage of implant supported restorations is retrievability. Implant restorations can be screw retained, cement retained or a combination of the two. Screw retained prostheses have a well documented history of application,17 and it is the authors' preference wherever possible. Retrievability is advantageous for reservicing, replacement, or salvaging of the restoration. There are often times when the restorative dentist may run into such problems as:

-

1

Loosening of the retaining screw,

- 2

-

3

Fracture of an abutment and

-

4

Modification of the prosthesis through loss of an implant.18

,,

Retrievability can be a significant safety factor. Screw retained prostheses have the advantage that they are more easily retrieved than those which are cemented.

Resistance to disease

Recurrent caries can occur beneath restorations, at the margins of restorations or on the root surfaces. Schwartz et al.19 reported caries to be the most frequent cause of failure of existing restorations. An assessment of disease susceptibility and control is essential prior to formulating a definitive treatment plan. Root surface caries is very prevalent amongst the elderly population and it is probable that this is associated with the reduced salivary flow resulting from the many drugs prescribed for patients in this age group. In patients who are disease susceptible, often decisions need to be made with regards to preserving teeth or choosing a more predictable long term option by the placement of dental implants. The patient in Figure 11 suffered from Alzheimer's disease and was unable to practice oral hygiene effectively. Note survival of implant supported restorations and deterioration of natural tooth abutments (Figs 17,18).

Reports of patients wearing removable partial dentures indicate that the health of the remaining dentition and surrounding soft tissue often deteriorates.20 Patients wearing removable partial dentures often exhibit greater mobility of the abutment teeth, greater plaque retention, increased bleeding on probing, more incidence of caries and accelerated bone loss in the edentulous regions.21 Aqulino et al.22 reported a 44% loss of abutment in patients wearing removable partial dentures over a 10 year period (Fig 18).

Implants have an added advantage in that they are not susceptible to dental caries and can preserve adjacent teeth. Often decisions need to be made as to when extraction and implant placement is a feasible option. A thorough risk analysis must be performed. Traditional wisdom was based upon the concept of trying to save the tooth by all means necessary. Even when patients presented with a significant amount of caries, clinicians favoured elective endodontics, crown lengthening and extra-coronal restorations. With the inception of dental implants a completely new avenue has been opened in the treatment planning process. There appear to be two schools of thought. One advocates the traditional approach while the other has adopted a more aggressive approach with treatment planning, and prefers to extract and replace a compromised tooth in a patient susceptible to caries with a dental implant and restoration.

Summary

Loss of teeth, eventual edentulism and the wearing of complete or partial dentures have been part of the expected course of ageing of the general population. Although patients may adapt well to both a complete and partial denture the decrease in masticatory function in comparison to a patient with a natural dentition has been well documented. Use of a removable prosthesis results in progressive bone resorption which compromises the denture bearing area compounding problems of retention and stability.

The goal of implant dentistry is to return a patient to oral health in a predictable fashion. Use of partial or complete dentures will not allow a patient to recover normal function, aesthetics, speech and comfort.

Implant supported prostheses offer a more predictable solution than traditional removable restorations. The many advantages passed on to the patient by use of implant supported restorations allow a patient to function with confidence and enjoy a better quality of life.

The next article in this series will focus on treatment planning for implants in the posterior quadrants.

References

Spiekerman H . Color atlas of dental medicine. Implantology. pp V–VI. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc, 1995.

Adell R, Eriksson B, Lekholm U et al. A long term follow up study of osseointegrated implants in the treatment of totally edentulous jaws. Int J Oral Maxillofac Impl 1990; 5: 347–359.

Lindhe T, Gunne J, Tillberg A et al. A meta analysis of implants in partial edentulism. Clin Oral Implants Res 1998; 9: 80.

Walton TR . An up to 15 year longitudinal study of 515 metal ceramic FPDs Part 1. Outcome. Int J Prosthodont 2002; 15: 439.

Goodacre CJ, Kan JY, Rungcharassaeng K et al. Clinical complications of osseointegrated implants. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 81: 537.

Naert I, Koutsikakis G, Duyck J et al. Biologic outcome of single implant restorations as tooth replacements. A long term follow up study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2000; 2: 209.

Schmitt A, Zarb G A . The longitudinal clinical effectiveness of osseointegrated dental implants for single tooth replacement. Int J Prosthodont 1993; 6: 187–202.

Haas R, Mensdorff-Pouilly N, Mailath G et al. Branemark single tooth implants, a preliminary report of 76 implants. J Prosthet Dent 1995; 73: 274–279.

Henry P H, Laney W R, Jemt T et al. Osseointegrated implants for single tooth replacement: a prospective 5 year multicenter study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1996: 450–455.

Roberts WE, Turley PK, Brezniak N et al. Bone physiology and metabolism. Calif Dent Assoc J 1987; 15: 54–61.

Pietrokovski J . The bony residual ridge in man. J Prosthet Dent 1975; 34: 456–462.

Tallgren A . The reduction in face height of edentulous and partially edentulous subjects during long term denture wear: a long term roentgenographic cephalometric study. Acta Odontol Scand 1966; 24: 195–239.

Carr A, Laney W B . Maximum occlusal force levels in patients with osseointegrated oral implant prostheses and patients with complete dentures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1987; 2: 101–110.

Rissin L, House J E, Manly R S et al. Clinical comparison of masticatory performance and electromyographic activity of patients with complete dentures, overdentures and natural teeth. J Prosthet Dent 1978; 39: 508–511.

Heath MR . The effect of maximum biting force and bone loss upon mastication function and dietary selection in the elderly. Int Dent J 1982; 32: 345–356.

Monteith BD . Management of loading forces on mandibular distal extension prostheses. Part 1: Evaluation of concepts for design. J Prosthet Dent. 1984 Nov; 52(5): 673–681.

Branemark P-I, Svensson B, Van Steenberghe D . Ten year survival rates of fixed prostheses on four or six implants ad modum Branemark in full edentulism. Clin Oral Impl Res 1995; 6: 227–231.

Konstantinos MX, Hiroyama H, Garefis PD . Cement retained vs screw retained implant restorations: A critical review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2003; 18: 5:719–728.

Schwartz N, Whitsett L, Berry R, Stewart J . Unserviceable crowns and fixed partial dentures: life span and causes of loss of serviceability. J Amer Dent Assoc 1970; 81: 1395–1401.

Waerhaug J . Periodontology and partial prostheses. Int Dent J 1968; 18: 101–107.

Wilding R, Reddy J . Periodontal disease in partial denture wearers: a biologic index. J Oral Rehabil 1987; 14 111–124.

Aquilino S A, Shugars D A, Bader J D et al. Ten year survival rates of teeth adjacent to treated and untreated posterior bounded edentulous spaces. J Prosthet Dent 2001; 85 455–460.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jivraj, S., Chee, W. Rationale for dental implants. Br Dent J 200, 661–665 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813718

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4813718

This article is cited by

-

Knowledge and perception about dental implants among undergraduate dental students

BDJ Open (2019)

-

Is the shortened dental arch still a satisfactory option?

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

A financial vacuum

British Dental Journal (2006)