Key Points

-

A surgical approach to a failed root canal treatment should only be considered when an orthograde approach is not possible.

-

The reason for failure should be carefully diagnosed before surgery is prescribed.

-

Modern periradicular surgery involves the use of an operating microscope, microsurgical instruments, and appropriate retrograde sealing materials

-

All surgical treatment should be followed-up, and encompassed in audit procedures.

Key Points

Endodontics

-

1

The modern concept of root canal treatment

-

2

Diagnosis and treatment planning

-

3

Treatment of endodontic emergencies

-

4

Morphology of the root canal system

-

5

Basic instruments and materials for root canal treatment

-

6

Rubber dam and access cavities

-

7

Preparing the root canal

-

8

Filling the root canal system

-

9

Calcium hydroxide, root resorption, endo-perio lesions

-

10

Endodontic treatment for children

-

11

Surgical endodontics

-

12

Endodontic problems

Abstract

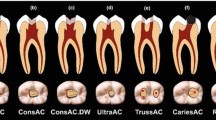

Root canal treatment usually fails because infection remains within the root canal. An orthograde attempt at re-treatment should always be considered first. However, when surgery is indicated, modern microtechniques coupled with surgical magnification will lead to a better prognosis. Careful management of the hard and soft tissues is essential, specially designed ultrasonic tips should be used for root end preparation which should ideally be sealed with MTA. All cases should be followed up until healing is seen, or failure accepted, and should form a part of clinical audit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although conventional orthograde root canal therapy must always be the preferred method of treating the diseased pulp, there are occasions when a surgical approach may be necessary. If orthograde treatment has failed to resolve the situation, the clinician should make every effort to ascertain why this has happened. A surgical approach is only indicated when it is agreed that orthograde retreatment is either not possible or will not solve the problem.

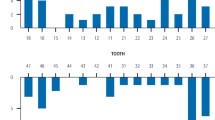

The two cases shown in Figures 1 and 2, both of which were referred for periradicular surgery, illustrate this point well. Figure 1 shows a radiograph of a lower molar that was causing symptoms, having first been obturated with silver points and subsequently suffered surgery when the problem did not resolve. The correct treatment should have been a repeat of the orthograde treatment to remove the infection from within the root canal space that was causing the failure. Figure 2 shows totally inadequate endodontic treatment. The case requires total dismantling and thorough orthograde retreatment.

There have been considerable developments in periradicular surgery, both in technique and materials, in recent years.1,2,3,4,5,6 Specialist practitioners routinely use surgical microscopes in conjunction with specially designed microsurgical instruments and retrograde filling materials. A description of these techniques is included in this chapter, and general practitioners are encouraged to compare this with their current practice, and adopt as many of these new procedures as possible. Alternatively, if these new techniques are not employed, greater consideration should be given to referral for specialist surgical treatment.

Indications for surgical intervention

Although endodontic surgery is carried out primarily in cases of failed orthograde treatment, there are other indications. Surgery may be necessary to establish drainage, (considered in Part 3); to biopsy a lesion; to repair any defects or perforations in the tooth root; to resect a multi-rooted tooth where, for technical reasons, one of the roots cannot be successfully treated.

Biopsy of a periapical lesion

The one specific indication for endodontic surgery is uncertainty about the nature of the apical lesion. The lesion should be excised in its entirety and sent for evaluation.

Root-end resection (apicectomy)

The term apicectomy refers to a stage of the operation only. The principal objective is to seal the canal system at the apical foramen from the periradicular tissues. To do this it is necessary to resect the apical part of the root to gain access to the root canal, hence the term. Root-end resection must be an adjunct measure to orthograde root treatment for two reasons. Firstly, there is very little chance of being able to seal all the lateral communications between the canal and the periodontal ligament with a retrograde root-filling technique. Secondly, the area of root-filling material exposed will be greater and the long-term success affected, because all root-filling materials are, to some extent, irritant to the tissues.

Indications for root-end resection

Improvements in root canal treatment techniques have lessened the need for apical surgery. Cases which at first seem obvious candidates for endodontic surgery may respond to conventional treatment provided careful thought is given to the aetiology. Once the decision has been made to carry out surgery, consideration must be given to the chances of success (see Part 12). Access and control of the operating environment are essential, otherwise the end result will be counterproductive.

Retreatment of a failed root filling

Surgery may be considered if a root filling fails and retreatment cannot be effected by orthograde means. There are a number of reasons why a root filling might fail, but generally this is due to inadequate cleansing and filling of the root canal. Some root fillings can prove very difficult to remove, for example hard setting pastes. Occasionally there may be an anatomical reason for the failure, such as an unfilled apical delta. Attempts at retreatment by a conventional orthograde route may be unsuccessful because the original canal cannot be negotiated. Periradicular surgery and root-end filling is therefore justified to ensure that the apical foramen has been sealed.

Root-filling material which has been extruded through the apical foramen may be a contributory cause of failure, since it could be an indication that the apical seal is deficient; necrotic material may be present at the apex and between the interface of the root filling and the canal wall; the root-filling material itself may be highly irritant (Fig. 3).

Procedural difficulties

During conventional orthograde root canal treatment, problems may arise as a result of one of the following:

-

Unusual root canal configurations (Fig. 4).

-

Extensive secondary dentine deposition (Fig. 5).

-

Fractured instruments within the root canal (Fig. 6).

-

Open apex (Fig. 7).

-

Existing post in the root canal unfavourable for dismantling (Fig. 8).

-

Lateral or accessory canal (Fig. 9).

Unusual root canal configurations

Instrumentation of canals in roots which exhibit bizarre morphology or severe dilaceration may prove impossible. Similarly, where there is an apical delta, thorough cleansing, shaping and obturation of the canal may prove impossible and surgery will be required to complement the orthograde approach.

Extensive secondary dentine deposition

The ageing process results in the deposition of secondary dentine, with a consequent reduction in size of the pulp chamber and the root canal. Even more profound sclerosis may result in a tooth which has been subjected to trauma. An asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis may result, bringing about sclerosis of the root canal system. The canals may then be almost completely obliterated and it may prove impossible to identify the canals with even the smallest instruments. Under these circumstances, continued searching deep in the root may result in excessive damage, weakening of the root, or even perforation. Periradicular surgery is then the only alternative to extraction.

Fractured instruments within the root canal

Instruments which have fractured in a root canal do not necessarily result in failure of the root treatment. They should be removed if possible, but if this is impossible, then an attempt should be made to seal the rest of the canal with the instrument in place. Surgery is only necessary if the tooth develops symptoms, or radiographic review shows a failure of healing. The incident should, of course, be recorded in the records, and the patient informed.

Open apex

Teeth that have been injured before root development is complete should be treated conventionally in the first instance. If the pulp is vital, then the coronal pulp is removed and the remaining vital radicular pulp is covered with calcium hydroxide to allow continued root development; this is termed 'apexogenesis'. If the pulp is irreversibly inflamed, then the radicular pulp is removed and the canal filled with calcium hydroxide to encourage root formation and closure of the apex; this is termed 'apexification'.7

However, should the treatment fail, then apical surgery may be necessary, to provide an apical seal after completion of the orthograde root filling. Care must be exercised when carrying out this operation as the root structure is often very delicate.

Existing post in the root canal

Periradicular surgery may be indicated for teeth with symptomatic periapical lesions which have satisfactory post crowns in place, provided the root filling in the main body of the canal is satisfactory. However, it has to be remembered that success depends on the canal system being completely sealed. If there is any doubt about this, it is better to remove the crown and post and carry out orthograde root treatment, avoid surgery, and thus provide a sound foundation for any subsequent restoration. Dismantling of post crowns is, however, not always straightforward. An assessment must be made of the length and shape of the post, the strength of the remaining root structure and, if possible, the cement used. Injudicious force during post removal may lead to root fracture and the loss of the tooth. The situation should be discussed in detail with the patient in order that informed consent to the chosen procedure is obtained.8

Lateral or accessory canal

Modern endodontic techniques should enable the root canal to be shaped adequately to permit flushing of sodium hypochlorite irrigation throughout the entire root canal system. Unfortunately, infected debris may occasionally persist in lateral or accessory canals. Whilst orthograde retreatment may be attempted, a surgical approach may be the only solution, particularly if these canals form part of the apical delta which may be eliminated by adequate surgical resection.

Surgical repair of roots

Surgery may be necessary to repair defects in a root surface due to either iatrogenic or pathological causes. The two main indications are as follows.

Perforations

Where possible, an orthograde approach should first be used to seal the perforation, ideally using mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA). If this is not practical, the canal must be thoroughly cleaned and filled with calcium hydroxide paste to dry it out and to allow the tissues time to heal. The prepared canal space should then be obturated using conventional root canal filling techniques. Perforations caused by instrumentation errors can usually be treated by an orthograde approach as the access is generally good. However, if clinical symptoms persist or there is bone resorption, or in the case of a large perforation as shown in Figure 10, a surgical approach will be necessary.

Internal and external root resorption

Internal resorption should always be treated by an orthograde route first. If the resorptive process has perforated through to the periodontal ligament, then surgery may be necessary to repair the root and provide an effective seal. Certain types of external root resorption in the early stages can be dealt with by surgery, provided access can be gained to the area (see root resorption).

Root amputation and hemisection

Periradicular surgery on a posterior tooth is a more difficult procedure to carry out than on an anterior tooth. For this reason, the relatively simpler techniques of root amputation or hemisection may be considered. The changes in endodontic and periodontal treatment techniques in recent years have greatly improved the prognosis for this form of treatment. The principal indications are endodontic, restorative or periodontal. Root amputation is an operation where one entire root of a multirooted tooth is removed, leaving the crown intact. Hemisection is the division of a tooth, usually in a buccolingual plane. Normally, one half of the tooth is removed, but both sections may be retained if there is disease in the furcation area only. However, the restorative problems this type of treatment poses are considerable and for this reason the prognosis is generally poor. Pre-operative assessment of both the periodontal and restorative aspects is crucial if these methods of treatment are contemplated.

Medical and dental considerations

Although there are few absolute contra-indications to endodontic surgery, a well-documented medical history is essential (see Part 2). In general, heart disease, diabetes, blood dyscrasias, debilitating illnesses and steroid therapy may contra-indicate surgery and special measures are necessary if surgery is contemplated. Consideration must also be given to psychological factors. As a rule, local analgesia is preferable, but patients who are particularly apprehensive may wish to have any surgery carried out under sedation. The choice of anaesthetic may also be governed by the nature of the operation, the site of the tooth and ease of access. A history of rheumatic fever is not a contra-indication for endodontic surgery, provided appropriate antibiotic cover is given. If there is any doubt about a patient's fitness to undergo any surgical endodontic procedure, then the patient's physician should always be consulted.

The first considerations are whether the tooth is worth saving and how important it is in the overall treatment plan. The general state of the mouth should be considered, both hard and soft tissues. The quality of restorative work in the tooth concerned should be particularly noted, and an assessment must also be made of the effects of any proposed surgery on the periodontal condition. The presence of any detectable dehiscence or bony fenestration will influence the design and extent of the flap.

A periapical radiograph should provide all the information required for assessment of the tooth, although it may be necessary to expose more than one film, from different angles. At least 3 mm of the periradicular tissues should be clearly visible. Assessment should be made of the root shape, taking into account any unusual curvature and the number of foramina that may be exposed at the apex as a consequence of the operation. If a sinus is present in the soft tissues, the sinus tract should be visualised by taking a radiograph with a gutta-percha point threaded into the tract, as shown in Part 2, Figure 5.

Good visual access is extremely important, and the anatomy of the area must be thoroughly understood. The position of any major structures such as neurovascular bundles and the maxillary sinus must be noted. A buccal or labial approach is always preferred, as a palatal approach is difficult and should only be undertaken in exceptional circumstances by experienced practitioners.

One of the key factors influencing the success or failure or periradicular surgery is the experience and expertise of the operator. Consideration should always be given to referral to an appropriate specialist, especially in difficult cases. A letter of referral should include a full clinical and medical history, and all relevant radiographs. Both the referring dentist and the specialist providing treatment have a responsibility to obtain informed consent to the procedure.

Periradicular surgery technique

The steps for carrying out this procedure are:

-

Pre-operative care.

-

Anaesthesia and haemostasis.

-

Soft-tissue management.

-

Hard-tissue management.

-

Curettage of area.

-

Resection of root.

-

Retrograde cavity preparation.

-

Retrograde filling.

-

Replacement of flap and suturing.

-

Post-operative care.

Pre-operative care

Although prophylactic antibiotic therapy is not usually required for routine periradicular surgery, systemic antibiotics may be required for any flare-ups prior to surgery. Chlorhexidine mouthwashes may also be beneficial, and these, together with systemic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, should be considered from the day prior to surgery.9

Anaesthesia and haemostasis

Wherever possible, local anaesthesia is the method of choice, although anxious patients who cannot be controlled with tranquillizers may also require intravenous sedation. The local anaesthesia injection also provides haemostasis, essential for good endodontic surgery. Following topical anaesthetic application, an anaesthetic solution with at least 1:80,000 adrenaline is injected slowly into several sites surrounding the surgical field. Local anaesthetic solutions containing Octapressin do not give adequate haemostasis and should be avoided if possible.

In the mandible, block injections should be given, in addition to infiltration of the tissues in the operating area. In the maxilla, the palate must be well infiltrated to anaesthetise the greater palatine nerve. The incisive papilla and canal must also receive sufficient anaesthetic solution to block the long sphenopalatine nerve. The local anaesthetic should be applied at least 10 minutes prior to surgery, to allow profound anaesthesia and maximum haemostasis.

Soft-tissue management

The design of the surgical flap should permit an unobstructed view of the operating area and permit easy access for instrumentation. The following points need to be considered:

-

The blood supply to the flap and adjacent tissues must be sufficient to prevent tissue necrosis when it is repositioned.

-

The edges of the flap should lie over sound bone and not cross any void; otherwise breakdown may occur and defective healing will result.

-

Relieving incisions should be vertical, and should not cross any bony eminence, for example the canine eminence, as healing will be poor, particularly if there is a dehiscence or fenestration present.

-

The incision must be clean, so that the flap can be reflected without any tearing of the margins.

-

The flap should always be full thickness and extend to the gingival sulcus. The periodontal tissues should be healthy, as healing will be affected by any overt disease.

There are several designs of flaps, and, whilst the choice may depend upon the size of the lesion, the periodontal status and the state of the coronal tooth structure, it usually depends upon the operator's preference.

Full mucoperiosteal flap

This design of flap provides the best possible access to all surgical sites, and can be either a rectangular flap with mesial and distal vertical relieving incisions, or triangular with just one. The former usually provides better access to the root apex in the anterior part of the mouth, though when operating on posterior teeth the distal relieving incision is not usually necessary, and may prove difficult to suture in the limited space available. The vertical relieving incisions are made firmly down the line angle of the teeth into the gingival crevice, taking in the papilla. The horizontal incision is made along the gingival crevice. The flap is then carefully reflected with a periosteal elevator lifting the periosteum with it from the bone. (Fig. 11a).

Semilunar flap

This flap, where an incision was made in a semicircle from near the apex of the adjacent tooth, onto the attached gingival, and finishing near the apex of the tooth on the other side, is mentioned purely for historical purposes, and is no longer recommended. Its main disadvantage is the scarring which invariably accompanies this design. However, problems also frequently occurred if the margins of the bony cavity extended across the incision line because the lesion proved to be much larger than was originally apparent (Fig. 11b).

Luebke–Oschenbein flap

The Luebke-Oschenbein flap was designed to overcome some of the disadvantages of the semilunar flap. A vertical incision is made down the distal aspect of the adjacent tooth to a point about 4.0 mm short of the gingival margin. The horizontal incision is scalloped following the contour of the gingival margin through the attached gingivae to the distal aspect of the tooth on the other side. The incision must always be extended to the other side of the fraenum and the distal aspect of the adjacent maxillary central or lateral incisor to avoid a vertical incision next to the fraenum (Fig. 11c).

The flap affords an excellent view of the operating area. However, it still has the disadvantage that the margins of the bony cavity might extend across the incision line, as can happen with the semilunar flap. It is essential to check if there is any periodontal pocketing, as breakdown will then be inevitable. The aim of this flap design is to preserve the integrity of the gingival margins if there are crowns on the teeth. Scarring may again be a problem with this type of flap.

Whatever design is used, the raised flap should be protected from damage during the operation, and should not be allowed to become desiccated.

Hard-tissue management

If the lesion has perforated the cortical plate, then location is a fairly simple matter. However, if this is not the case, then measurement of the tooth from the radiograph taken with a long-cone paralleling technique must be made. Initially, a large size round bur, cooled by copious water or sterile saline, may be used to provide small, shallow exploratory holes to locate the site of the apex and the lesion. This must be done very carefully, to avoid damaging the root surfaces of the teeth in the immediate area. Alternatively, a round bur, again carefully cooled, may be used to locate the apex by paring away the cortical bone over the apex. The bone is shaved away with a very light motion to reduce the heat generated and improve visibility. Sufficient bone should be removed using the bur and curettes until good visual access to the root end is obtained.

Periradicular curettage

The object of this procedure is to remove any soft-tissue lesion with curettes from around the root apex. It may not be possible to remove all the soft tissue until the root end has been resected.

Periradicular curettage used to be a routine operation carried out by many practitioners after completion of a root canal filling. The rationale for this is no longer accepted, because if the root filling has been carried out successfully and the canal system has been sealed, then healing of the lesion will take place without surgical intervention.

When undertaking periradicular surgery, as much as possible of the periapical lesion should be removed. However, the soft tissues in a periapical lesion are essentially reparative and defensive in nature and if other anatomical structures are liable to be damaged some tissue may be left. This is fortunate as, technically, it is difficult to remove every trace of the lesion, especially if it is firmly attached to the wall of the bone cavity.

Pathological material removed should be sent for histopathological examination with full clinical details.

Armamentarium

For all surgical procedures, instruments should be set out, preferably in the order in which they will be used. A typical layout is shown in Fig. 12, and includes the modern microsurgical instruments. Magnification, with either optical loupes or a surgical microscope, is preferable.

Resection of the root

The aim of resection is to present the surface of the root so that the apical limit of the canal can be visually examined and to provide access for retrograde cavity preparation. Approximately 3 mm of root is removed which will include almost all lateral canals.10 It is not necessary to resect the apex to the base of the bony cavity. If too much root is removed, then a greater cross- section of the canal will be revealed, exposing a larger area of filling material to the tissues, and thus reducing the chances of successful healing. The amount of available root length has to be considered for any future post crown construction. There is also an inherent disadvantage as the crown—root ratio is reduced, which may affect the adaptive response of the periodontal ligament to excessive occlusal forces.

A straight fissure bur is used with copious water spray at right angles to the long axis of the tooth. Older textbooks may describe bevelling of the cut root surface at approximately 45° to the long axis of the tooth. This is no longer recommended as this form of resection may result in both incomplete removal of the apical delta, and unnecessary enlargement of the exposed root canal.11 Magnification is strongly recommended for this procedure, both for accuracy in visualising the true angulation of the long axis, and also for detailed inspection of the cut root surface and root canal.

Retrograde cavity preparation

Root-end preparation should ideally be performed with a piezo-electric ultrasonic handpiece. If this is not available then a small, round bur should be used in a miniature-headed handpiece, to prepare a single surface cavity to include the entire root canal. Care must be taken to ensure that the canal is penetrated sufficiently far for an effective seal to be placed. Inaccuracy may result in a cavity that is both too large and too shallow. The clinician practising without the aid of magnification must be aware of these difficulties, and the consequent reduction in prognosis of the surgery.

It is now recommended therefore that the retrograde cavity is prepared with specially designed ultrasonic tips used in a piezo-electric handpiece. These were first introduced in the early 1990s and the KiS® tips are illustrated in Figure 13.12 Used with a gentle planing motion along the canal configuration, at a low power setting, a depth of 3 mm may be prepared quickly and cleanly. The cavity should be examined carefully before proceeding to restoration.

Retrograde filling

Before the retrograde filling is inserted, haemostasis must be achieved. Dry epinephrine-impregnated cotton wool balls may be placed into the bony cavity, and will also provide a barrier to prevent accidental loss of excess filling material around the root. Bone wax or ribbon gauze may also be used to isolate the root tip. If gauze is used, it may be wetted with local anaesthetic solution or saline once it is in place, then dabbed dry with a cotton wool pledget. Any excess filling material is more easily retained by the damp gauze.

A biologically compatible material should be used, and amalgam is no longer recommended. A reinforced zinc oxide–eugenol cement such as IRM (modified by the addition of 20% polymethacrylate) or Super EBA (modified with the addition of ethoxybenzoic acid) is recommended. Reinforced glass-ionomer cements or composite resin may be used, although these materials are more technique sensitive.

However, especially when microsurgery is being employed with appropriate magnification, mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) (Fig. 14) is recommended.5 It is the least toxic, the most biocompatible, hydrophilic and gives the best seal. The root end should be dried with paper points or a fine air syringe, and the material may be placed in small increments using a carrier such as the one illustrated in Figure 16a. Alternatively, the MTA may be condensed into a tube shape using the device illustrated in Figure 16b, when it may be carried to the operation site on a probe. Once placed and compacted into the cavity, a damp cotton wool pledget may be used to compress the material and remove excess. Note carefully that the dental surgery assistant must ensure that all instruments, especially the carriers, are thoroughly cleaned of every trace of MTA immediately following surgery, or they may become clogged and rendere useless. Figure 15

Whichever material is selected for the restoration, it should be thoroughly compacted into the cavity with a small plugger to ensure a dense fill, and burnished with a ball-ended instrument to a smooth finish. The bony cavity should be carefully debrided to ensure that all materials and debris are removed.

Replacement of flap and suturing

Once the retrograde filling has been completed, the packing around the root removed and final debridement carried out, the flap may be sutured into place. Where possible, synthetic monofilament sutures should be used as these do not cause wicking of bacteria into the surgical site and lead to better healing than when silk sutures are used. Resorbable sutures are not recommended.

The vertical relieving incisions should be repaired with interrupted sutures. The gingival margin should be carefully repositioned and sutured with sling sutures. Commencing at a buccal papilla, the suture is taken through the embrasure, around the tooth and back through the adjacent embrasure to enter the next papilla. The suture is then taken back round the tooth to the original site and the knot tied over the buccal papilla. The sutures may be removed after 48 hours, and certainly no more than 3–4 days, when the periodontal fibres will have reattached. Sutures left longer than this may actually delay healing by wicking.

Post-operative care

Immediately following suturing, the tissues should be firmly compressed with a damp gauze for 5 minutes. Post-operative swelling can be reduced by the continued application of cold compresses (crushed ice cubes placed in a plastic bag surrounded by a clean soft cloth) for up to 6 hours. Post-operative pain may be controlled by the administration of a long-acting local anaesthetic at the end of the surgery, and by the prescription of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Chlorhexidine mouthwash should be used to keep the surgical site clean until the sutures are removed. The prescription of antibiotics is only necessary if required by the patient's medical history.

Surgical outcomes

A radiograph should be exposed either immediately following treatment or when the sutures are removed for comparison with future films to assess healing. Ideally, cementum and periodontal ligament should regenerate over the resected root apex, although in many cases repair occurs by the formation of a fibrous scar. It is reported that success rates may vary between 30% and 80%.13,14 It should be noted, however, that recent papers have reported treatment using the modern techniques described here to have success rates as high as 92%.15

Should failure occur, the cause must be established before further intervention. Repeat surgery has a low success rate, as can be seen in Figure 16. All surgical treatment should, of course, be encompassed within audit and clinical governance, both for the patient and the clinician (Fig. 17).

References

Kim S . Principles of endodontic surgery. Dent Clin North Am 1997; 41: 481–497.

Peters L, Wesselink P . Soft tissue management in endodontic surgery. Dent Clin North Am 1997; 41: 513–528.

Chindia ML, Valderhaug J . Periodontal status following trapezoidal and semilunar flaps in apicectomy. East African Med J 1995; 72: 564–567.

Morgan LA, Marshall JG . A scanning electron microscopic study of in vivo ultrasonic root-end preparations. J Endod 1999; 25: 567–570.

Torabinejad M, Pitt Ford TR, Abedi HR, Kariyawasam SP, Tang HM . Tissue reaction to implanted root-end filling materials in the tibia and mandible of guinea pigs. J Endod 1998; 24: 468–471.

Kim S . Endodontic Microsurgery. Chapter 19 in Cohen S, Burns R C, Pathways of the Pulp. St Louis: Mosby 2002.

Webber RT . Apexogenesis versus apexification. Dent Clin North Am 1984; 28: 669–697.

Layton S, Korsen J . Informed consent in oral and maxillofacial surgery: a study of the value of written warnings. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1994; 32: 34–36.

Martin MV, Nind D . Use of chlorhexidine gluconate for pre-operative disinfection of apicectomy sites. Br Dent J 1987; 162: 459–461.

Hsu YY, Kim S . The resected root surface. The issue of canal isthmuses. Dent Clin North Am 1997; 41: 529–540.

Gilheany PA, Figdor D, Tyas MJ . Apical dentin permeability and microleakage associated with root end resection and retrograde filling. J Endod 1994; 20: 22–26.

Carr G . Common errors in periradicular surgery. Endod Rep 1993; 8: 12–16.

Jansson L, Sandstedt P, Laftman AC, Skogland A . Relationship between apical and marginal healing in periradicular surgery. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Path, Oral Rad, Endod 1997; 83: 596–601.

Rud J, Andreasen JO, Jensen JE . Radiographic criteria for the assessment of healing after endodontic surgery. Int J Oral Surg 1972; 1: 195–214.

Maddalone M, Gagliani M . Periapical endodontic surgery: a 3-year follow-up study. Int Endod J 2003; 36: 193–198.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carrotte, P. Surgical endodontics. Br Dent J 198, 71–79 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811970

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811970