Abstract

Introduction This research investigates framing in online patient information for those newly diagnosed with periodontitis.

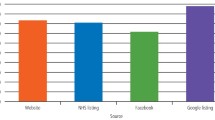

Methods This study is a cross-sectional analysis of websites using corpus linguistic techniques. A Google search was conducted with the term 'gum disease.' Ten pages of search results were reviewed and information available was separated into types of resource: retail, healthcare, and dental practice websites. The dataset was analysed in terms of word frequency, collocation and keyness as compared to the British National Corpus Written Sampler. Differences between sources were assessed.

Results Across combined data sources, there was a tendency for the most advanced symptoms of periodontitis to be given prominence. There was also a negative skew towards avoidance of negative outcomes of treatment rather than achieving positive ones. When comparing types of resource, retail websites tended to be more positive, with a focus on improving 'milder' stages of disease.

Conclusions Negative framing could potentially induce engagement with treatment and self-care by the process of 'fear-appeal'; however, there is a risk that negativity demotivates an already anxious patient. Further research is required to evaluate patient perceptions of the information and to investigate effects this could have on behaviour change.

Key points

-

Investigates online resources available to periodontal patients and the language used.

-

Highlights that resources tend to focus on symptoms of more advanced disease, while treatment is discussed in terms of avoiding negative outcomes rather than achieving positive outcomes.

-

This framing of information may have implications for patient attendance and motivation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 24 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $10.79 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

White D A, Tsakos G, Pitts N B et al. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: common oral health conditions and their impact on the population. Br Dent J 2012; 213: 567-572.

Miranda-Rius J, Brunet-Llobet L, Lahor-Soler E. The Periodontium as a Potential Cause of Orofacial Pain: A Comprehensive Review. Open Dent J 2018; 12: 520-528.

Caton J G, Armitage G, Berglundh T et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions - Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Periodontol 2018; DOI: 10.1002/JPER.18-0157.

Papapanou P N, Susin C. Periodontitis epidemiology: is periodontitis under-recognized, over-diagnosed, or both? Periodontol 2000 2017; 75: 45-51.

Durham J, Fraser H M, McCracken G I, Stone K M, John M T, Preshaw P M. Impact of periodontitis on oral health-related quality of life. J Dent 2013; 41: 370-376.

Ferreira M C, Dias-Pereira A C, Branco-de-Almeida L S, Martins C C, Paiva S M. Impact of periodontal disease on quality of life: a systematic review. J Periodontal Res 2017; 52: 651-665.

Graziani F, Tsakos G. Patient-based outcomes and quality of life. Periodontol 2000 2020; 83: 277-294.

Page R C, Schroeder H E. Pathogenesis of inflammatory periodontal disease. A summary of current work. Lab Invest 1976; 34: 235-249.

Tonetti M S, Jepsen S, Jin L, Otomo-Corgel J. Impact of the global burden of periodontal diseases on health, nutrition and wellbeing of mankind: A call for global action. J Clin Periodontol 2017; 44: 456-462.

Albury C, Hall A, Syed A et al. Communication practices for delivering health behaviour change conversations in primary care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Fam Pract 2019; 20: 111.

Grady C, Cummings S R, Rowbotham M C, McConnell M V, Ashley E A, Kang G. Informed Consent. New Eng J Med 2017; 376: 856-867.

Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 1981; 211: 453-458.

Entman R M. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J Comm 1993; 43: 51-58.

Hajiagha A P, Nourozi S, Yekaninejad M S, Mansouri A, Chaibakhsh S. Effect of message framing on improving oral health behaviours in students in Qazvin, Iran. J Isfahan Dent School 2013; 8: 512.

Pakpour A H, Yekaninejad M S, Sniehotta F F, Updegraff J A, Dombrowski S U. The effectiveness of gain-versus loss-framed health messages in improving oral health in Iranian secondary schools: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med 2014; 47: 376-387.

Brick C, McCully S N, Updegraff J A, Ehret P J, Areguin M A, Sherman D K. Impact of Cultural Exposure and Message Framing on Oral Health Behaviour: Exploring the Role of Message Memory. Med Decis Making 2016; 36: 834-843.

Divdar M, Araban M, Heydarabadi A B, Cheraghian B, Stein L A. Effectiveness of message-framing to improve oral health behaviours and dental plaque among pregnant women. Arch Public Health 2021; 79: 117.

Sherman D K, Updegraff J A, Mann T. Improving oral health behaviour: a social psychological approach. J Am Dent Assoc 2008; 139: 1382-1387.

Uskul A K, Sherman D K, Fitzgibbon J. The cultural congruency effect: Culture, regulatory focus, and the effectiveness of gain-vs. loss-framed health messages. J Experiment Soc Psychol 2009; 45: 535-541.

Arora R. Message framing and credibility: application in dental services. Health Mark Q 2000; 18: 29-44.

Akl E A, Oxman A D, Herrin J et al. Framing of health information messages. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006777.pub2.

Rosenstock I M, Strecher V J, Becker M H. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q 1988; 15: 175-183.

Ajzen I. Attitudes and personality traits. In Attitudes, Personality and Behaviour. pp 2-4. Chicago: Dorsey Press, 1988.

Heideker S, Steul-Fischer M. The Effects of Message Framing and Ad Credibility on Health Risk Perception. Market ZFP J Res Manag 2017; 39: 49-64.

Young M E, Norman G R, Humphreys K R. The role of medical language in changing public perceptions of illness. PLoS One 2008; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003875.

Landrine H, Corral I. Separate and unequal: residential segregation and black health disparities. Ethn Dis 2009; 19: 179-184.

Almashat S, Ayotte B, Edelstein B, Margrett J. Framing effect debiasing in medical decision making. Patient Educ Couns 2008; 71: 102-107.

Hu J, Luo E, Song E et al. Patients' attitudes towards online dental information and a web-based virtual reality programme for clinical dentistry: A pilot investigation in China. Int J Med Inform 2009; 78: 208-215.

Hanna K, Sambrook P, Armfield J M, Brennan D S. Internet use, online information seeking and knowledge among third molar patients attending public dental services. Aust Dent J 2017; 62: 323-330.

Wang X, Shi J, Kong H. Online Health Information Seeking: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Commun 2021; 36: 1163-1175.

Bizzi I, Ghezzi P, Paudyal P. Health information quality of websites on periodontology. J Clin Periodontol 2017; 44: 308-314.

Schwendicke F, Stange J, Stange C, Graetz C. German dentists' websites on periodontitis have low quality of information. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2017; 17: 114.

Kanmaz B, Buduneli N. Evaluation of information quality on the internet for periodontal disease patients. Oral Dis 2021; 27: 348-356.

Booth A. Clear and present questions: formulating questions for evidence based practice. Library Hi Tech 2006; 24: 355-368.

Ćurković M, Košec A. Bubble effect: including internet search engines in systematic reviews introduces selection bias and impedes scientific reproducibility. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18: 130.

Ernst N, Kühne R, Wirth W. Effects of Message Repetition and Negativity on Credibility Judgements and Political Attitudes. Int J Commun 2017; 11: 1-21.

Rayson P. From key words to key semantic domains. Int J Corpus Linguist 2008; 13: 519-549.

Martínez-Hinarejos C-D, Benedí J-M, Granell R. Statistical framework for a Spanish spoken dialogue corpus. Speech Commun 2008; 50: 992-1008.

Mishra S, Gregson M, Lalumiere M L. Framing effects and risk-sensitive decision making. Br J Psychol 2012; 103: 83-97.

Kasebaum N J, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray C J, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systemic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res 2014; 93: 1045-1053.

Nordby H. Medical explanations and lay conceptions of disease and illness in doctor-patient interaction. Theor Med Bioeth 2008; 29: 357-370.

James P, Worthington H V, Parnell C et al. Chlorhexidine mouthrinse as an adjunctive treatment for gingival health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008676.pub2.

Armfield J M, Heaton L J. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Aust Dent J 2013; 58: 390-407.

De Stefano R. Psychological Factors in Dental Patient Care: Odontophobia. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019; 55: 678.

French D P, Cameron E, Benton J S, Deaton C, Harvie M. Can Communicating Personalised Disease Risk Promote Healthy Behaviour Change? A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Ann Behav Med 2017; 51: 718-729.

Tannenbaum M B, Hepler J, Zimmerman R S et al. Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychol Bull 2015; 141: 1178-1204.

Carter A E, Carter G, Boschen M, AlShwaimi E, George R. Pathways of fear and anxiety in dentistry: A review. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2: 642-653.

Kok G, Peters G-J Y, Kessels L T E, Ten Hoor G A, Ruiter R A C. Ignoring theory and misinterpreting evidence: the false belief in fear appeals. Health Psychol Rev 2018; 12: 111-125.

Partington A. Modern Diachronic Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies (MD-CADS) on UK newspapers: an overview of the project. Corpora 2010; 5: 83-108.

Mautner G. Corpora and critical discourse analysis. In Contemp Corpus Linguist. pp 32-46. London: Continuum, 2009.

Kelly D, Azzopardi L. How many results per page? A study of SERP size, search behaviour and user experience. In Proceedings of the 38th international ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. pp 183-192. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015.

Hallyburton A, Evarts L A. Gender and Online Health Information Seeking: A Five Survey Meta-Analysis. J Consum Health Internet 2014; 18: 128-142.

Baumann E, Czerwinski F, Reifegerste D. Gender-Specific Determinants and Patterns of Online Health Information Seeking: Results From a Representative German Health Survey. J Med Internet Res 2017; DOI: 10.2196/jmir.6668.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Joanne Beaumont: conceptualisation of research, data collection, analysis and writing of the manuscript. Neil Cook: supervision of research and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval was not required as there was no formal patient involvement and no confidential information was accessed.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beaumont, J., Cook, N. Analysis of types of and language used in online information available to patients with periodontitis. Br Dent J 234, 253–258 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5525-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5525-2

This article is cited by

-

Mind your language

British Dental Journal (2023)