Abstract

Background

Individuals affected by disasters are at risk for adverse mental health sequelae. Individuals living in the US Gulf Coast have experienced many recent major disasters, but few studies have explored the cumulative burden of experiencing multiple disasters on mental health.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate the relationship between disaster burden and mental health.

Methods

We used data from 9278 Gulf Long-term Follow-up Study participants who completed questionnaires on perceived stress, anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in 2011–2013. We linked 2005–2010 county-level data from the Spatial Hazard Events and Losses Database for the United States, a database of loss-causing events, to participant’s home address. Exposure measures included total count of loss events as well as severity quantified as property/crop losses per capita from all hazards. We used multilevel modeling to estimate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each exposure–outcome relationship.

Results

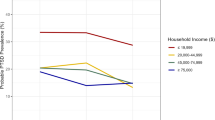

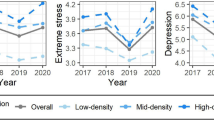

Total count of loss events was positively associated with perceived stress (ORQ4:1.40, 95% CI:1.21–1.61) and was inversely associated with PTSD (ORQ4:0.66, 95% CI:0.45–0.96). Total duration of exposure was also associated with stress (ORQ4:1.16, 95% CI:1.01–1.33) but not with other outcomes. Severity based on cumulative fatalities/injuries was associated with anxiety (ORQ4:1.31, 95% CI:1.05–1.63) and stress (ORQ4:1.34, 95% CI:1.15–1.57), and severity based on cumulative property/crop losses was associated with anxiety (ORQ4:1.42, 95% CI:1.12–1.81), depression (ORQ4:1.22, 95% CI:0.95–1.57) and PTSD (ORQ4:1.99, 95% CI:1.44–2.76).

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Desai B, Maskrey A, Peduzzi P, De Bono A, Herold C. Making development sustainable: the future of disaster risk management, global assessment report on disaster risk reduction. 2015. https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:78299.

McGlade J, Bankoff G, Abrahams J, Cooper-Knock S, Cotecchia F, Desanker P, et al. Global assessment report on disaster risk reduction: 2019. https://doi.org/10.18356/83cdc99a-en.

FEMA. FEMA reflects on historic year. 2017. https://www.fema.gov/news-release/2017/12/29/fema-reflects-historic-year.

Lazzaroni S, van Bergeijk PAG. Natural disasters’ impact, factors of resilience and development: a meta-analysis of the macroeconomic literature. Ecol Econ. 2014;107:333–46.

Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2008;38:467–80.

Norris FH, Tracy M, Galea S. Looking for resilience: understanding the longitudinal trajectories of responses to stress. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:2190–8.

Fernandez A, Black J, Jones M, Wilson L, Salvador-Carulla L, Astell-Burt T, et al. Flooding and mental health: a systematic mapping review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4393088/.

Schwartz RM, Tuminello S, Kerath SM, Rios J, Lieberman-Cribbin W, Taioli E. Preliminary assessment of hurricane harvey exposures and mental health impact. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5982013/.

Schwartz RM, Sison C, Kerath SM, Murphy L, Breil T, Sikavi D, et al. The impact of Hurricane Sandy on the mental health of New York area residents. Am J Disaster Med. 2015;10:339–46.

Lieberman-Cribbin W, Liu B, Schneider S, Schwartz R, Taioli E. Self-reported and FEMA flood exposure assessment after Hurricane Sandy: association with mental health outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2017;12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5271356/.

Yabe H, Suzuki Y, Mashiko H, Nakayama Y, Hisata M, Niwa S-I, et al. Psychological distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident: results of a mental health and lifestyle survey through the Fukushima Health Management Survey in Fy2011 and Fy2012. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2014;60:57–67.

Laugharne J, Watt GV, de, Janca A. After the fire: the mental health consequences of fire disasters. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:72–7.

Hansen A, Bi P, Nitschke M, Ryan P, Pisaniello D, Graeme T. The effect of heat waves on mental health in a temperate Australian city. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1369–75.

Belleville G, Ouellet M-C, Morin CM. Post-traumatic stress among evacuees from the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfires: exploration of psychological and sleep symptoms three months after the evacuation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 May;16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6540600/.

Gall M., & Cutter S. L. Events and Outcomes: Beyond Hurricane Katrina. In: Emergency Management: The American Experience, 2005, 1900, p. 188–193.

Blake ES, Landsea C, Gibney EJ 1971-. The deadliest, costliest, and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts). National Hurricane Center (1965-1995), editor. 2011; Available from: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/6929.

Kwok RK, Engel LS, Miller AK, Blair A, Curry MD, Jackson WB, et al. The GuLF Study: a prospective study of persons involved in the deepwater horizon oil spill response and clean-up. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:570–8.

Engel LS, Kwok RK, Miller AK, Blair A, Curry MD, McGrath JA, et al. The Gulf long-term follow-up study (GuLF STUDY): biospecimen collection at enrollment. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2017;80:218–29.

Cohen S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: The social psychology of health. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1988. p. 31–67. (The Claremont Symposium on Applied Social Psychology).

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7.

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–73.

Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, Camerond RP, Hugelshofer DS, Shaw-Hegwer J, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC–PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry. 2004;9:9–14.

Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, et al. Screening for Serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:184–9.

CEMHS. The spatial hazard events and losses database for the United States, Version 18.1. Phoenix, AZ: Arizona State University; 2019. http://www.sheldus.org.

Gall M, Borden KA, Cutter SL. When do losses count? Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2009;90:799–810.

Smith AB, Matthews JL. Quantifying uncertainty and variable sensitivity within the US billion-dollar weather and climate disaster cost estimates. Nat Hazards. 2015;77:1829–51.

“About the Survey.” The United States Census Bureau. September 26, 2019. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/about.html.

Hahn DJ, Viaud E, Corotis RB. Multihazard mapping of the United States. ASCE-ASME J Risk Uncertain Eng Syst Part Civ Eng. 2017;3:04016016. https://doi.org/10.1061/AJRUA6.0000897.

Hubbard AE, Ahern J, Fleischer NL, Laan MV, der, Lippman SA, Jewell N, et al. To GEE or Not to GEE: comparing population average and mixed models for estimating the associations between neighborhood risk factors and health. Epidemiology 2010;21:467.

Ramezani N. Analyzing correlated data in SAS®. 2017;13. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings17/1251-2017.pdf.

Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins J. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. 1999;10:37–48.

Stewart PA, Stenzel MR, Ramachandran G, Banerjee S, Huynh T, Groth C, et al. Development of a total hydrocarbon ordinal job-exposure matrix for workers responding to the deepwater horizon disaster: the GuLF STUDY. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2018;28:223–30.

US Census Bureau. 2006-2010 ACS 5-year Estimates. 2010. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2010/5-year.html.

Goldmann E, Galea S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:169–83.

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM, Mulder RT. Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1025–31.

Stellman JM, Smith RP, Katz CL, Sharma V, Charney, LaVallee RA, et al. Enduring mental health morbidity and social function impairment in world trade center rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers: the psychological dimension of an environmental health disaster. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1248–53.

McMillan GP, Lapham S. Effectiveness of Bans and Laws in reducing traffic deaths. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1944–8.

Harville EW, Shankar A, Dunkel Schetter C, Lichtveld M. Cumulative effects of the Gulf oil spill and other disasters on mental health among reproductive-aged women: the Gulf Resilience on Women’s Health study. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2018;10:533–41.

Seery MD, Holman EA, Silver RC. Whatever does not kill us: cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability, and resilience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;99:1025.

Kwok RK, McGrath JA, Lowe SR, Engel LS, Jackson WB, Curry MD, et al. Mental health indicators associated with oil spill response and clean-up: cross-sectional analysis of the GuLF STUDY cohort. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e560–7.

Lowe S, Kwok R, Payne J, Engel L, Galea S, Sandler D. Why does disaster recovery work influence mental health?: pathways through physical health and household income. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58:354–64.

Rung AL, Gaston G, Oral E, Robinson WT, Fontham E, Harrington DJ, et al. Depression, mental distress, and domestic conflict among louisiana women exposed to the deepwater horizon oil spill in the WaTCH study. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1429–35.

McKinzie AE. In their own words: disaster and emotion, suffering, and mental health. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2018;13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5844051/.

Pietrzak RH, Tracy M, Galea S, Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Hamblen JL, et al. Resilience in the face of disaster: prevalence and longitudinal course of mental disorders following hurricane Ike. PLoS ONE. 2012;7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3383685/.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press; 2012. p. 593.

Myers CA, Slack T, Singelmann J. Social vulnerability and migration in the wake of disaster: the case of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Popul Environ. Cambridge, UK; 2008;29:271–91.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH Common Fund and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [ZIA ES 102945].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants completing the home visit.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, M.D., Lawrence, K.G., Gall, M. et al. Natural hazards and mental health among US Gulf Coast residents. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 31, 842–851 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-021-00301-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-021-00301-z