Abstract

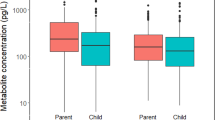

To address concerns among Gulf Coast residents about ongoing exposures to volatile organic compounds, including benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, o-xylene, and m-xylene/p-xylene (BTEX), we characterized current blood levels and identified predictors of BTEX among Gulf state residents. We collected questionnaire data on recent exposures and measured blood BTEX levels in a convenience sample of 718 Gulf residents. Because BTEX is rapidly cleared from the body, blood levels represent recent exposures in the past 24 h. We compared participants’ levels of blood BTEX to a nationally representative sample. Among nonsmokers we assessed predictors of blood BTEX levels using linear regression, and predicted the risk of elevated BTEX levels using modified Poisson regression. Blood BTEX levels in Gulf residents were similar to national levels. Among nonsmokers, sex and reporting recent smoky/chemical odors predicted blood BTEX. The change in log benzene was −0.26 (95% CI: −0.47, −0.04) and 0.72 (0.02, 1.42) for women and those who reported odors, respectively. Season, time spent away from home, and self-reported residential proximity to Superfund sites (within a half mile) were statistically associated with benzene only, however mean concentration was nearly an order of magnitude below that of cigarette smokers. Among these Gulf residents, smoking was the primary contributor to blood BTEX levels, but other factors were also relevant.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 6 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $43.17 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1999.

NTP. Report on Carcinogens: Benzene. National Toxicology Program, Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

Goldstein BD. Benzene as a cause of lymphoproliferative disorders. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;184:147–50.

Wallace LA. Major sources of benzene exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 1989;82:165–9.

Ilgen E, Karfich N, Levsen K, Angerer J, Schneider P, Heinrich J, et al. Aromatic hydrocarbons in the atmospheric environment: Part I. Indoor versus outdoor sources, the influence of traffic. Atmos Environ. 2001;35:1235–52.

Lin YS, Egeghy PP, Rappaport SM. Relationships between levels of volatile organic compounds in air and blood from the general population. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2008;18:421–9.

Wallace L. Environmental exposure to benzene: an update. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104:1129.

Symanski E, Stock TH, Tee PG, Chan W. Demographic, residential, and behavioral determinants of elevated exposures to benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes among the U.S. population: results from 1999-2000 NHANES. J Toxicol Environ Health. 2009;72(Pt A):915–24.

Bolden AL, Kwiatkowski CF, Colborn T. New look at BTEX: are ambient levels a problem? Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49: 5261–76.

Egeghy PP, Tornero-Velez R, Rappaport SM. Environmental and biological monitoring of benzene during self-service automobile refueling. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:1195–202.

Singh HB, Salas L, Viezee W, Sitton B, Ferek R. Measurement of volatile organic chemicals at selected sites in California. Atmos Environ. 1992;26:2929–46.

Jia C, Batterman S, Godwin C. VOCs in industrial, urban and suburban neighborhoods, Part 1: Indoor and outdoor concentrations, variation, and risk drivers. Atmos Environ. 2008;42: 2083–100.

Grattan LM, Roberts S, Mahan WT Jr., McLaughlin PK, Otwell WS, Morris JG Jr. The early psychological impacts of the deepwater horizon oil spill on Florida and Alabama communities. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:838–43.

Solomon GM, Janssen S. Health effects of the gulf oil spill. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304:1118–9.

Kostiainen R. Volatile organic compounds in the indoor air of normal and sick houses. Atmos Environ. 1995;29:693–702.

Wallace L, Pellizzari E, Hartwell TD, Perritt R, Ziegenfus R. Exposures to benzene and other volatile compounds from active and passive smoking. Arch Environ Health. 1987;42:272–9.

Grady SJ, Casey GD. Occurrence and distribution of methyl tert-butyl ether and other volatile organic compounds in drinking water in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States, 1993–1998. U.S. Geological Survey and Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2001. Contract No.: 00-4228.

López E, Schuhmacher M, Domingo JL. Human health risks of petroleum-contaminated groundwater. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2008;15:278–88.

Arnold SM, Angerer J, Boogaard PJ, Hughes MF, O’Lone RB, Robison SH, et al. The use of biomonitoring data in exposure and human health risk assessment: benzene case study. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2013;43:119–53.

Pierce CH, Chen YL, Hurtle WR, Morgan MS. Exponential modeling, washout curve reconstruction, and estimation of half-life of toluene and its metabolites. J Toxicol Environ Health-Part A. 2004;67:1131–58.

ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Benzene. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2007.

ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Xylene. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2007.

ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Ethylbenzene. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2010.

ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Toluene. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2015.

Churchill JE, Ashley DL, Kaye WE. Recent chemical exposures and blood volatile organic compound levels in a large population-based sample. Arch Environ Health: Int J. 2001;56:157–66.

Uddin MS, Blount BC, Lewin MD, Potula V, Ragin AD, Dearwent SM. Comparison of blood volatile organic compound levels in residents of Calcasieu and Lafayette Parishes, LA, with US reference ranges. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24:602–7.

Kwok R, Engel L, Miller A, Blair A, Curry M, Jackson II W, et al. The GuLF STUDY: a prospective study of persons involved in the Deepwater Horizon oil spill response and clean-up. Environ Health Perspect. 2017;125:570–578

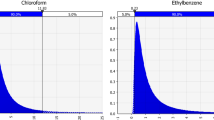

Blount BC, Kobelski RJ, McElprang DO, Ashley DL, Morrow JC, Chambers DM, et al. Quantification of 31 volatile organic compounds in whole blood using solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B. 2006;832: 292–301.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Laboratory Method: Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) in whole blood. Emergency Response and Air Toxicants Branch Division of Laboratory Sciences, National Center for Environmental Health. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2005-2006/labmethods/vocwb_d_met_volatile-organic-compounds.pdf.

Chambers DM, McElprang DO, Waterhouse MG, Blount BC. An improved approach for accurate quantitation of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, and styrene in blood. Anal Chem. 2006;78: 5375–83.

CDC. 2007–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. National Center for Health Statistics 2015. National Center for Health Statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2007-2008/questionnaires07_08.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyData. 4 Oct 2017; Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017.

Williams R, Rea A, Vette A, Croghan C, Whitaker D, Stevens C, et al. The design and field implementation of the Detroit Exposure and Aerosol Research Study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009;19:643–59.

Chambers DM, Blount BC, McElprang DO, Waterhouse MG, Morrow JC. Picogram measurement of volatile n-alkanes (n-hexane through n-dodecane) in blood using solid-phase microextraction to assess nonoccupational petroleum-based fuel exposure. Anal Chem. 2008;80:4666–74.

Chambers DM, McElprang DO, Mauldin JP, Hughes TM, Blount BC. Identification and elimination of polysiloxane curing agent interference encountered in the quantification of low-picogram per milliliter methyl tert-butyl ether in blood by solid-phase microextraction headspace analysis. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2912–9.

Jia C, Ward KD, Mzayek F, Relyea G. Blood 2,5-dimethyfuran as a sensitive and specific biomarker for cigarette smoking. Biomarkers. 2014;19:457–62.

Chambers DM, Ocariz JM, McGuirk MF, Blount BC. Impact of cigarette smoking on volatile organic compound (VOC) blood levels in the U.S. population: NHANES 2003-2004. Environ Int. 2011;37:1321–8.

Lubin JH, Colt JS, Camann D, Davis S, Cerhan JR, Severson RK, et al. Epidemiologic Evaluation of Measurement Data in the Presence of Detection Limits. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112: 1691–6.

Whitcomb BW, Schisterman EF. Assays with lower detection limits: implications for epidemiological investigations. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:597–602.

Jia C, Batterman S, Godwin C. VOCs in industrial, urban and suburban neighborhoods—Part 2: Factors affecting indoor and outdoor concentrations. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:2101–16.

Sexton K, Adgate JL, Church TR, Ashley DL, Needham LL, Ramachandran G, et al. Children’s exposure to volatile organic compounds as determined by longitudinal measurements in blood. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;113:342–9.

Wallace LA, Pellizzari ED, Hartwell TD, Sparacino C, Whitmore R, Sheldon L, et al. The TEAM study: personal exposures to toxic substances in air, drinking water, and breath of 400 residents of New Jersey, North Carolina, and North Dakota. Environ Res. 1987;43:290–307.

Wheeler AJ, Wong SL, Khoury C, Zhu J. Predictors of indoor BTEX concentrations in Canadian residences. Health Rep. 2013;24:11.

Fan AZ, Prescott MR, Zhao G, Gotway CA, Galea S. Individual and community-level determinants of mental and physical health after the deepwater horizon oil spill: findings from the gulf States population survey. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2015;42:23–41.

McCoy MA, Salerno JA, (eds). Assessing the Effects of the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill on Human Health. New Orleans, LA: National Academy of Sciences; 2010.

Simon-Friedt BR, Howard JL, Wilson MJ, Gauthe D, Bogen D, Nguyen D, et al. Louisiana residents’ self-reported lack of information following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill: Effects on seafood consumption and risk perception. J Environ Manag. 2016;180:526–37.

Wilson MJ, Frickel S, Nguyen D, Bui T, Echsner S, Simon BR, et al. A targeted health risk assessment following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure in Vietnamese-American shrimp consumers. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:152–9.

Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6.

Chambers DM, Ocariz JM, McGuirk MF, Blount BC. Impact of cigarette smoking on Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) blood levels in the U.S. Population: NHANES 2003–2004. Environ Int. 2011;37:1321–8.

Census Bureau urban-rural classification 2016. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/urban-rural.html.

Sammarco PW, Kolian SR, Warby RA, Bouldin JL, Subra WA, Porter SA. Concentrations in human blood of petroleum hydrocarbons associated with the BP/deepwater horizon oil spill, Gulf of Mexico. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90:829–37.

Batterman SSF-C, Li S, Mukherjee B, Jia C. Personal exposure to mixtures of volatile organic compounds: modeling and further analysis of the RIOPA data. Boston, MA: Health Effects Institute; 2014.

Wu XM, Fan ZT, Zhu X, Jung KH, Ohman-Strickland P, Weisel CP, et al. Exposures to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and associated health risks of socio-economically disadvantaged population in a “hot spot” in Camden, New Jersey. Atmos Environ. 2012;57:72–9.

ATSDR. Interaction profile for: benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes (BTEX). Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry; 2004.

Boberg E, Lessner L, Carpenter DO. The role of residence near hazardous waste sites containing benzene in the development of hematologic cancers in upstate New York. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2011;24:327–38.

Gorber CS, Schofield-Hurwitz S, Hardt J, Levasseur G, Tremblay M. The accuracy of self-reported smoking: a systematic review of the relationship between self-reported and cotinine-assessed smoking status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:12–24.

Lioy PJ, Fan ZH, Zhang J, Georgopoulos P, Wang S, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Personal and ambient exposures to air toxics in Camden, New Jersey. Boston, MA: Health Effects Institute. 2011;160:3–127

Zabiegala B, Urbanowicz M, Namiesnik J, Gorecki T. Spatial and seasonal patterns of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes in the Gdansk, Poland and surrounding areas determined using radiello passive samplers. J Environ Qual. 2010;39:896–906.

Atari DO, Luginaah IN, Gorey K, Xu X, Fung K. Associations between self-reported odour annoyance and volatile organic compounds in ‘Chemical Valley’, Sarnia, Ontario. Environ Monit Assess. 2013;185:4537–49.

Soto-Garcia L, Ashley WJ, Bregg S, Walier D, LeBouf R, Hopke PK, et al. VOCs emissions from multiple wood pellet types and concentrations in indoor air. Energy Fuels 2015;29:150911132333008.

Wolkoff P. How to measure and evaluate volatile organic compound emissions from building products. A perspective. Sci Total Environ. 1999;227:197–213.

Yamada H. Contribution of evaporative emissions from gasoline vehicles toward total VOC emissions in Japan. Sci Total Environ. 2013;449:143–9.

Harrison RMD-SJ, Baker SJ, Aquilina N, Meddings C, Harrad S, Matthews I, Vardoulakis S. HRA measurement and modeling of exposure to selected air toxics for health effects studies and verification by biomarkers. Boston, MA: Health Effects Institute; 2009.

Jia C, Batterman SA, Relyea GE. Variability of indoor and outdoor VOC measurements: an analysis using variance components. Environ Pollut. 2012;169:152–9.

IARC. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: benzene. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2012.

Rappaport SM, Kim S, Lan Q, Vermeulen R, Waidyanatha S, Zhang L, et al. Evidence that humans metabolize benzene via two pathways. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:946–52.

Hays SM, Pyatt DW, Kirman CR, Aylward LL. Biomonitoring equivalents for benzene. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2012;62:62–73.

Pierce C, Chen Y, Hurtle W, Morgan M. Exponential modeling, washout curve reconstruction, and estimation of half-life of toluene and its metabolites. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A. 2004;67:1131–58.

Paustenbach D, Galbraith D Biomonitoring and biomarkers: exposure assessment will never be the same. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1143-9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Julianne Payne, Audra Hodges, and Mark Bodkin for data management on this project.

Funding

This work was funded by the NIH Common Fund and the Intramural Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01 ES 102945).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Werder, E.J., Gam, K.B., Engel, L.S. et al. Predictors of blood volatile organic compound levels in Gulf coast residents. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 28, 358–370 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-017-0010-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41370-017-0010-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association of the blood levels of specific volatile organic compounds with nonfatal cardio-cerebrovascular events in US adults

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Occurrence of BTEX from petroleum hydrocarbons in surface water, sediment, and biota from Ubeji Creek of Delta State, Nigeria

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2021)

-

Determinants of environmental styrene exposure in Gulf coast residents

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2019)

-

Developing Large-Scale Research in Response to an Oil Spill Disaster: a Case Study

Current Environmental Health Reports (2019)