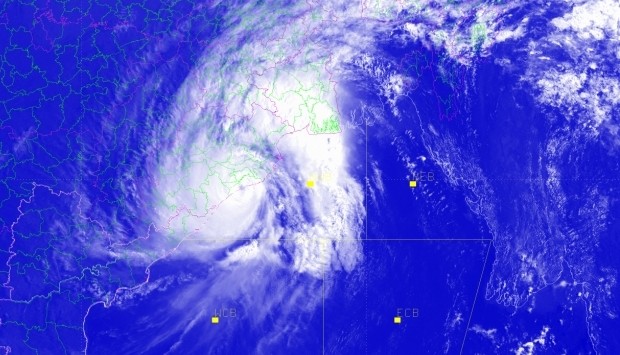

Satellite image showing the eye of cyclone Fani at the time of landfall near Puri on 3 May 2019. © M. Mohapatra and A. Sharma/IMD

The devastation caused by tropical cyclone Fani, which ravaged the eastern Indian state of Odisha on 3 May 2019, has refocused attention on the grim outlook for the state in the face of climate change, experts say.

Odisha, like its neighbours Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal, has seen some of the worst ever cyclones in India’s history. Between 1891 and 2018, the state was hit by about 110 cyclones, says tropical meteorologist Uma Charan Mohanty, a visiting professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Bhubaneswar. “That’s a massive number.”

Well-documented evidence shows that many cyclones turn and steer in the Bay of Bengal to make Odisha a common landfall destination.

That’s only likely to get worse as climate change increases sea surface temperatures and triggers more intense tropical cyclones, says Preeti Tewari, an associated professor of geography at the University of Delhi.

According to the 2013 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), fewer tropical cyclones will form as the climate gets warmer, but a higher fraction of these will be intense and cause more damage.

The report also points to the higher likelihood of enhanced summer monsoon precipitation and increased rainfall extremes of landfall cyclones on the coasts of the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea.This will be unwelcome news to residents of the state whose lives are already plagued by extreme weather conditions such as thunderstorms, heat waves, floods and droughts.

When the ‘Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm’ Fani (pronounced Foni, meaning ‘the hood of a snake’ in Bangla) made landfall close to the pilgrim town of Puri this month, wind speeds exceeded 200 km per hour.

Thanks to a superb pre-cyclone evacuation exercise, the Odisha administration moved over 1.2 million coastal people to safety, earning global commendation for the effort. Some 64 people were killed in the storm, which left thousands of others homeless, without electricity and safe water, and robbed the popular coast-hugging marine drive road between Puri and Konark of its pristine green cover.

Satellite image showing the eye of cyclone Fani at the time of landfall near Puri on 3 May 2019. © M. Mohapatra and A. Sharma/IMD

Odisha Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik’s first message post-cyclone on 4 May reflected the dismay that many experts and locals were feeling. Patnaik emphasised that Fani was one of the rarest of rare cyclones during summer time – the first in 43 years to hit Odisha in summer and one of the 3 to hit the state during this season in the last 150 years. Most cyclones in the bay are formed during June-August, the monsoon season, or post-monsoon in October-November. This made tracking and prediction of the cyclone very challenging for his government. “In fact, until 24 hours of landfall, one was not sure about the trajectory it was going to take because of the predictions of different agencies.”

For a state vulnerable to tropical cyclones, Fani, which Patnaik called ‘close to a super cyclone’, puts the spotlight back on such recurring and progressively intense weather phenomena in the Bay of Bengal and the post-cyclone preparedness of India’s east-coastal states.

A cyclone hotbed

What makes the Bay of Bengal such a hot spot for cyclones? It is a core area of cyclone formation for this location – most cyclones that hit the region are formed here and many of them make landfall. Of the 36 deadliest tropical cyclones in the world, 27 have arisen to India’s East.

Wind patterns in the Arabian Sea to India’s West keep oceans cooler, resulting in fewer storms. On the eastern coast, however, storms are more intense and a flatter topography that is unable to deflect the winds allows them to move easily landwards.

The super cyclone of 1999, the strongest ever to hit India, killed more than 10,000 people after landfall in Odisha and unleashed such devastation that took years for the state to come back to normal. In recent memory, cyclone Phailin (2013) also caused massive damage to the state.

“Geographically, the landmass between Puri to Bhadrak in the map of Odisha juts out a little into the sea, making it vulnerable to any cyclonic activity in the Bay of Bengal,” says meteorologist Sarat Chandra Sahu, the retired Director of the India Meteorological Department’s Regional Meteorological Science Centre in Odisha’s capital Bhubaneswar.

Sahu, who now heads the Centre for environment and climate at a private university Sikhsa ‘O’ Anusandhan, says even though some other cyclones – Hudhud (2014) and Titli (2018) – did not make landfall in Odisha, they caused severe damage to coastal towns. “It’s almost like one cyclone every other year now.”

Harsher local weather

With the coastal canopy along the Puri-Konark marine drive blown away by Fani’s strong winds, Odisha is predicted to have more local heating through the rest of its already severe summer.

“Though climate-wise cyclonic storms do not [usually] have much impact on weather, because of the severe loss of green cover, the local weather or micro-climate will certainly be affected making for enhanced human suffering,” says Sushil Kumar Dash from the Centre for Atmospheric Sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi.

Dash, also the President of the Indian Meteorological Society, says a summer cyclone is not ‘completely unusual’ but the severity of Fani is worth taking note. “It does corroborate the IPCC’s estimates of more intense cyclones in future.”

The summer was already harsh, with the mercury pushing past 40 degrees Celsius in most parts of Odisha even a week before Fani struck. The fierce storm was short-lived, with not much rain. “It recurved and went towards Bangladesh, dragging along whatever little moisture was there in the air,” Sahu says predicting a hotter local weather for the rest of the summer.

Stripped of basic amenities such as water and power supply for days after the cyclone, the people of Odisha are waiting for monsoon to bring some relief from the heat wave, hopefully in the second week of June.