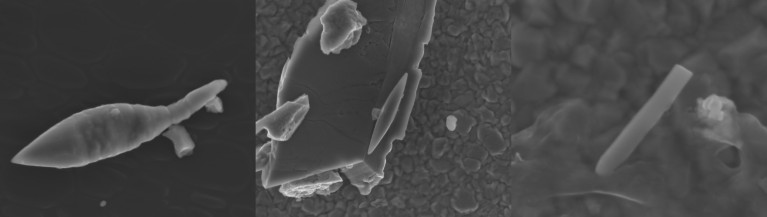

Needle, spindle, bullet and spearhead shape-magnetofossils. Credit: Kadam, N et al.

Scientists have unearthed giant magnetofossils — large magnetic crystals left behind by microorganisms — buried in 50,000-year-old sediment in the Bay of Bengal1. They are the youngest giant magnetofossils reported till now.

Magnetotactic bacteria create nanometre-sized crystals, composed of magnetite or greigite, to navigate changing redox conditions in the water column or saturated sediment. The crystals, known as magnetofossils, are left when the organisms die.

These fossils contribute to sediments’ magnetic signal, offering information about changes in past environments.

Scientists led by CSIR-National Institute of Oceanography, Goa, extracted a sediment core almost 3 metres long from the southwestern Bay of Bengal, fed by the sediment-carrying Godavari, Krishna and Penner rivers.

The core, composed mainly of silty clays, revealed both benthic (occurring at the bottom of a body of water) and planktic (floating or drifting in water) foraminifera — single-celled organisms with shells.

Using magnetic analysis and electron microscopy on core section samples, the team identified giant magnetofossils with needle, spindle, bullet and spearhead shapes. The magnetofossils are present throughout sediment core spanning the last 42,700 years.

The researchers suggest that when reactive iron and organic carbon carried by rivers entered the oxygen-starved Bay of Bengal, the bioavailable iron combined with organic carbon as a food source helped the giant magnetofossil-producing organisms to grow.

The authors say as long as these environmental conditions persist, the organisms responsible for producing giant magnetofossils will thrive.