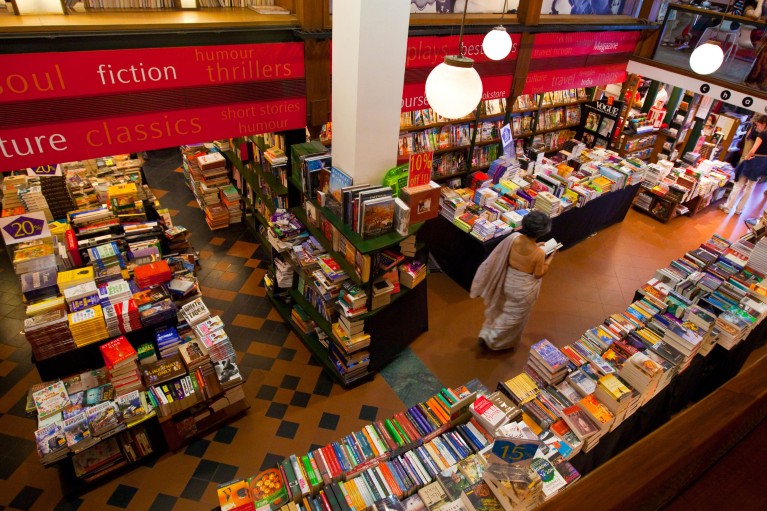

The science fiction book portfolio of Indian publishers is lean. Credit: dbtravel/Alamy

A prevalent conclusion from the recent India Science Festival in Hyderabad was that the country doesn’t produce enough books on science for general audiences.

Non-academic science books play an important role in making complex scientific concepts and discoveries easier for readers to understand and imagine the possible applications and implications of science. Despite shrinking reader-attention span, books continue to engage, influence, and transform mindsets. Popular science books inspire curiosity among children and the young and help them make better sense of the world.

The first popular English-language science books came to India in the mid-20th century. Even today, a majority of popular science books in Indian bookstores or online marketplaces are in English and written by foreign authors. The lack of Indian stories and perspectives is stark. While bestsellers in politics, cultural fiction, entertainment, and sports dominate the Indian market and have won prestigious international awards, compelling literature on Indian science and scientists is rare. It also likely accounts for the limited penetration of any popular book on science.

An estimate by the Association of Publishers in India suggests that the Indian publishing industry is expected to become an Rs 800 billion behemoth by 2024. Commercial publishing operates in a dynamic economic environment with fragmented regional distribution networks and shifting technological and regulatory landscapes. As a result, commercial publishers rely on genres and authors with guaranteed markets. Two Indian commercial book publishers when contacted said their portfolio of popular science books was lean and they were interested in expanding the genre. Moreover, these publishers may not be abreast of advances or debates in science and technology. Neither do they have people to appraise book proposals or manuscripts on scientific themes. But are Indians writing enough books on science to begin with?

19th and 20th century scientists wrote in engaging styles, making their discoveries and inventions more understandable. These scientists had a deep understanding of a variety of disciplines and political and social realities of their times. As a result, pioneers such as Charles Darwin, Carl Sagan, Richard Feynman, Jagadish Chandra Bose, Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar and Jayant Narlikar not only pursued questions of the natural world but were also celebrated authors and poets. Their nonfiction and fiction conveyed new concepts, knowledge, and worldviews, serving as a chronicle of scientific progress.

Science fiction is a popular genre that continues to push the limits of thought and practice to create possible futures. As Indian science fiction writer Manjula Padmanabhan notes in The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction “we live in an era when only a whisper-thin membrane separates science fiction from science fact”. The blurring of this line between fact and fiction can be seen in the works of celebrated authors such as H G Wells, Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury.

In 1896, one of the earliest works on science fiction from India by the celebrated scientist Jagdish Chandra Bose Niruddesher Kahini (The Story of the Missing One), alluded to the ‘butterfly effect’, a scientific phenomenon established much later in 1960.

Regional writers in India have produced many science fiction books in Marathi and Bengali. But limitations of language and circulation may have come in the way of their wider popularity. Interestingly, the burst of science-fiction writing in Maharashtra and West Bengal coincided with the active People Science Movements in these states during the 1960s and 1970s.

Fiction allows science to be interpreted and challenged within a complex and ever-changing technological as well as socio-cultural milieu, inviting non-scientists into its fold.

Earlier science had to keep up with science fiction speculations. Today, with breakneck scientific progress, fiction writers are scrambling not only to make sense of complex science but also its diverse implications.

China recognises the potential of science fiction to inspire innovative and disruptive ideas among its youth. The internet has played a huge role in popularising science fiction in China providing open and free platforms for writers to showcase their work, receive feedback, and gain following. The Three-Body Problem, one of the most successful novels from Asia, has firmly placed Chinese science fiction on the global stage. India is yet to produce works of that calibre or popularity.

Sadly, current academic training robs scientists of their creative writing skills and due to intense professional competition, they neither have the time nor the inclination to pursue them. Institutions barely support scientists if they wish to write a non-academic book.

Science and technology are rapidly transforming our lives. They require the same level of public attention as politics and business. We must find ways to improve academic culture and scientific training and nurture science communication as an important skill for scientists. Scientific institutions must create and maintain archives that can document their findings. These efforts need financial and non-financial investments as well as collective pride in the country’s scientific history and contemporary advances.