Summary:

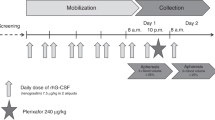

We verified the possibility of collecting large amounts of peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) to support three courses of adjuvant high-dose dense chemotherapy (HDDC) with high-dose epirubicin, preceded by dexrazoxane, and high-dose paclitaxel, in patients with high-risk breast cancer (⩾9 positive nodes). The mobilizing regimen consisted of high-dose epirubicin 150 mg/m2, preceded by dexrazoxane 1000 mg/m2 (day 1), given in combination with paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 (day 2), plus filgrastim. Of the 25 patients enrolled, one went off study due to a severe hypersensitivity reaction to paclitaxel, another did not undergo leukapheresis due to fever persistent after hematological recovery, while in 23 patients an adequate number of PBSCs was collected by a single leukapheresis. The median number of CD34+, CD34+/CD33−, and CD34+/CD38− cells collected per patient was 17 × 106/kg, 13.4 × 106/kg, and 1.5 × 106/kg, respectively. Neutropenia was the only grade 4 toxicity and lasted a median of 3 days. High-dose epirubicin, preceded by dexrazoxane for the first time used in mobilizing regimen, and paclitaxel plus filgrastim are effective in releasing large amounts of PBSCs, which can then be safely employed to support multiple courses of HDDC.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hortobagyi GN . Treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 974–984.

Pedrazzoli P, Perotti C, Da Prada GA et al. Collection of circulating progenitor cells after epirubicin, paclitaxel and filgrastim in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1997; 75: 1368–1372.

Zibera C, Pedrazzoli P, Ponchio L et al. An epirubicin/paclitaxel combination mobilizes large amounts of hematopoietic progenitor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer showing optimal response to the same chemotherapy regimen. Haematologica 1999; 84: 924–929.

Bengala C, Pazzagli I, Tibaldi C et al. Mobilization, collection, and characterization of peripheral blood hemopoietic progenitors after chemotherapy with epirubicin, paclitaxel, and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor administered to patients with metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer 1998; 82: 867–873.

Rosti G, Albertazzi L, Ferrante P et al. Epirubicin+G-CSF as peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) mobilizing agents in breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 1995; 6: 1045–1047.

Burtness BA, Psyrri A, Rose M et al. A phase I study of paclitaxel for mobilization of peripheral blood progenitor cells. Bone Marrow Transplant 1999; 23: 311–315.

Lopez M, Vici P, Di Lauro L et al. Randomized prospective clinical trial of high-dose epirubicin and dexrazoxane in patients with advanced breast cancer and soft tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 86–92.

Hensley ML, Schuchter LM, Lindley C et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guidelines for the use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy protectants. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 3333–3355.

Stewart THM, Retsky MW, Tsai SCJ, Verma S . Dose response in the treatment of breast cancer. Lancet 1994; 343: 402–404.

Wood WC, Budman DR, Korzun AH et al. Dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II, node-positive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1253–1259.

Bastholt L, Dalmark M, Gjedde SB et al. Dose–response relationship of epirubicin in the treatment of postmenopausal patients with metastatic breast cancer: a randomized study of epirubicin at four different dose levels performed by the Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol 1996; 14: 1146–1155.

Brufman G, Colajori E, Ghilezan N et al. Doubling epirubicin dose intensity (100 mg/m2 versus 50 mg/m2) in the FEC regimen significantly increases response rates. An international randomised phase III study in metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 1997; 8: 155–162.

Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 1205–1211.

French Adjuvant Study Group . Benefit of a high-dose epirubicin regimen in adjuvant chemotherapy for node-positive breast cancer patients with poor prognostic factors: five years follow-up results of FASF 05 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2000; 19: 602–611.

Gianni AM, Siena S, Bregni M et al. Efficacy, toxicity, and applicability of high-dose sequential chemotherapy as adjuvant treatment in operable breast cancer with 10 or more involved axillary nodes: five-year results. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 2312–2321.

Basser RL, To LB, Collins JP et al. Multicycle high-dose chemotherapy and filgrastim-mobilized peripheral-blood progenitor cells in women with high-risk stage II or III breast cancer: five year follow-up. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 82–92.

Hudis C, Seidman A, Baselga J et al. Sequential dose-dense doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and cyclophosphamide for resectable high-risk breast cancer: feasibility and efficacy. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17: 93–100.

Lalisang RI, Voest EE, Wils JA et al. Dose-dense epirubicin and paclitaxel with G-CSF: a study of decreasing intervals in metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2000; 82: 1914–1919.

Cottu PH, Extra JM, Espie M et al. High-dose sequential epirubicin and cyclophosphamide with peripheral blood stem cell support for advanced breast cancer: results of a phase II study. Br J Cancer 2001; 85: 1240–1246.

Elias AD, Richardson P, Avigan D et al. A short course of induction chemotherapy followed by two cycles of high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell rescue for chemotherapy naive metastatic breast cancer. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001; 27: 269–278.

Schrama JG, Baars JW, Holtkamp MJ et al. Phase II study of a multi-course high-dose chemotherapy regimen incorporating cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, and carboplatin in stage IV breast cancer. Bone Marrow Transplant 2001; 28: 173–180.

Norton L, Simon R . The Norton–Simon hypothesis revisited. Cancer Treat Rep 1986; 70: 163–169.

National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0. Http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html.

Peters WP, Ross M, Vrenenburgh JJ et al. High-dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow support as consolidation after standard-dose adjuvant therapy for high-risk primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 1993; 11: 1132–1143.

Hasinoff BB, Hellmann K, Herman EH, Ferrans VJ . Chemical biological and clinical aspects of dexrazoxane and other bisdioxopiperazines. Curr Med Chem 1998; 5: 1–28.

Tetef ML, Synold TW, Chow W et al. Phase I trial of 96-hour continuous infusion of dexrazoxane in patients with advanced malignancies. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7: 1569–1576.

Langer SW, Sehesyed M, Jensen PB . Dexrazoxane is a potent and specific inhibitor of anthracycline induced subcutaneous lesions in mice. Ann Oncol 2001; 12: 405–410.

Liesmann J, Belt R, Haas C, Hoogstraten B . Phase I evaluation of ICRF-187 (NSC-169780) in patients with advanced malignancy. Cancer 1981; 47: 1959–1962.

Gomez-Espuch J, Moraleda JM, Ortuno F et al. Mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells with paclitaxel (taxol) as a single chemotherapeutic agent, associated with rhG-CSF. Bone Marrow Transplant 2000; 25: 231–235.

Demirer T, Rowley S, Buckner CD et al. Peripheral-blood stem-cell collections after paclitaxel, cyclophosphamide, and recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13: 1714–1719.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Italian National Research Council (Project no. 31412), and by a grant from Istituto Oncologico Romagnolo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Giorgi, U., Rosti, G., Zaniboni, A. et al. High-dose epirubicin, preceded by dexrazoxane, given in combination with paclitaxel plus filgrastim provides an effective mobilizing regimen to support three courses of high-dose dense chemotherapy in patients with high-risk stage II–IIIA breast cancer. Bone Marrow Transplant 32, 251–255 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704125

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704125

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multiple cycles of PBPC-supported high-dose carboplatin and paclitaxel following mobilization with epirubicin and cisplatin are feasible but ineffective in treating patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2007)

-

A randomized study comparing filgrastim versus lenograstim versus molgramostim plus chemotherapy for peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2006)