Abstract

The irritation scale is a widely used and reliable self-report scale for measuring cognitive and emotional strain related to the work environment. It extends existing measures by providing a sensitive assessment for pre-clinical stress at work. Existing normative data are based on convenience samples and are therefore not representative. This study provides new normative data for the irritation scale based on a representative German sample (N = 1480). The new normative data indicate that the overall level of irritation in the German workforce is significantly lower compared to previously published data. Convergent and discriminant validity is confirmed by correlations with depression and anxiety (Patient Health Questionnaire-4 for Depression and Anxiety), somatic symptom scales (Bodily Distress Syndrome 25 checklist, Somatic Symptom Scale-8, Giessen Subjective Complaints List-8, comorbidity), psychological functioning (Mini-ICF rating for activity and participation disorders in mental illness), work-related stressors (overcommitment and bullying) and individual resources (self-efficacy). The results confirm the utility of the irritation scale and provide new benchmarks that avoid an underestimation of the levels of irritation in future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Instruments that assess work-related psychological strain are important for identifying risks for health impairments and unfavorable work design. If these are detected at an early stage, preventive action can be taken. In the workplace context, preventing disease is more cost-effective than treating it1. In addition, it has a positive impact on the quality of life of employees2. The concept of irritation is an established indicator for the assessment of psychosocial strain at work3. It was first introduced by Mohr and is based on the assumption that mental impairment results from a perceived goal discrepancy, which is expressed by both increased mental preoccupation with work-related issues (cognitive irritation, CI) and irritability (emotional irritation, EI)4. Both aspects are captured by the irritation scale (IS)5. The IS is a frequently used instrument that is able to identify psychological strain at work at an early stage6,7. Based on the developmental model of impairment of psychological well-being8, it is considered a mediator between (social) stressors and depressive symptoms9. The scale is recommended for the evaluation of interventions10,11,12 and for the early detection of psychosomatic complaints13, among others. The eight items of the irritation scale have been translated and validated in several different languages3. Mohr, Müller et al. provided normative data of the irritation scale by analyzing data from 20 different data sets (total N = 4030 individuals)6. The data sets were convenience samples with partly high strain occupational groups (e.g. police officers and firefighters). The aim of this paper is to present current norms, review the factorial structure of the scale and present both new and confirmatory evidence regarding construct validity of the irritation scale based on a representative German sample. Since the first normative data of the IS scale presented by Mohr et al. was not based on a representative sample, which could have distorted the correlations with validity measures (e.g., Warr14), we examine the construct validity on the base of data representative for working adults in Germany. For this purpose, correlations with clinical indicators (depressive and anxious symptoms, psychosomatic complaints, psychological functioning), with work stressors (overcommitment, bullying), and with individual resources (self-efficacy) were considered.

Specific hypotheses regarding construct validity

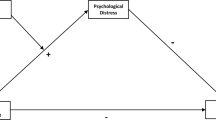

From the perspective of theoretical models of goal discrepancy and mental health15,16, irritation is regarded as a non-clinical precursor of clinical mental impairments. It can therefore be assumed that irritation has a positive correlation with clinical symptoms such as depression, anxiety, somatic complaints and reduced general mental functioning.

To the author's knowledge, only subclinical depression measures have been used to date to evaluate the association of IS with depressive symptoms9,17. The Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ)-418 has been established as an ultra-brief, excellent screening tool of depression and anxiety. In the presented data, its relationship to irritation will be examined. According to the results of Dormann et al., a medium to high positive correlation is expected9.

Possible correlations with somatic complaints are also of interest. These are often the trigger for seeking medical help when psychological problems such as depression are present and can be evaluated as an alarm signal for high stress19. A medium positive correlation of the IS with various somatic complaints is expected, based on the correlations found so far by Müller et al. with psychosomatic complaints16. In this study, we use different instruments to record psychosomatic complaints (Bodily Distress Syndrome 25 checklist, Somatic Symptom Scale, Giessen Subjective Complaints List, comorbidity).

When mental and somatic difficulties occur, it usually affects functioning in everyday life20. Thus, if the IS is related to depression, anxiety, and somatic complaints, a relationship to functioning is also expected. The Mini-ICF rating for activity and participation disorders in mental illness (Mini-ICF-APP-S)21 captures illness-related ability impairment and covers more areas than the PHQ-4 or the somatic scales. A positive relationship can be assumed.

In addition to the presumed relationships with clinical factors, Irritation is considered a medium-term consequence of work-related stressors3. Bullying or mobbing is one of the work stressors associated with the highest risk for mental health, as it systematically undermines social resources22. Thus, a positive correlation of IS with bullying, measured with the Mobbing Intensity of Colleagues (MOB-C)23, can also be expected. Also, the relationship with work-related overcommitment24 will be investigated, which has not been reported in the literature so far. A very high positive correlation is expected, especially with the subscale CI, since the constructs overlap strongly.

Moreover, self-efficacy is thought as a personal resource that acts as a mediator between stress and mental health25. Accordingly, high values of IS are expected to be accompanied by low self-efficacy values16.

In addition to the presumed direction and strength of the correlations, certain assumptions can be made about the extent to which the subscales EI and CI correlate differently with the respective constructs. From the model of goal discrepancy15 it can be concluded that EI shows a closer correlation to clinical psychological symptoms than CI: Ruminations in the sense of CI are seen as direct reactions to a perceived goal discrepancy resulting from work stressors, for example. Here, CI represents the cognitive simulation of possible solution strategies to overcome this discrepancy. If efforts to reach the goal remain in vain, frustration and irritability follow in the sense of EI, which is thus seen as a direct precursor to mental diseases. In this respect, we suspect stronger associations of all clinical constructs with the EI subscale, compared to CI.

Materials and methods

Sample characteristics

The present study was based on a representative survey on physical and mental well-being in the German population. Data were collected by USUMA (Independent Service for Surveys, Methods and Analyses, Berlin) between May and July 2019. Written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the University of Leipzig (No. 145/19-ek) and all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The sample consisted of a total of 2531 persons. The sample included 1350 females and 1181 males with an average age of 48.44 (sd = 17.86). For more details on the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample see the supplementary table. The survey followed ADM (Arbeitskreis Deutscher Markt-und Sozialforschungsinstitute e.V.) sampling guidelines for generating a representative sample of the German population26. Weighting variables provided by USUMA were applied, which correct for the increased selection probability of individuals in small households and the distortions due to a lack of willingness to participate on the part of randomly selected individuals. All analyses were calculated with the weighted values. Participants with missing values of the IS were excluded (n = 1020). Since the IS is a work-related instrument, only persons with valid IS-values who worked at least 15 h per week (n = 1406) were included in the analysis. Offsetting this with the sampling weights yields a new N = 1480 for all further analyses. For calculating the internal consistency of the other scales, the full sample size of N = 2531 was used.

Irritation scale (IS)

The IS contains eight items answered on a scale between 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree). The two primary-order factors emotional irritation (EI) (sum score of items 3, 5, 6, 7, 8; range from 5 to 35) and cognitive irritation (CI) (sum score of items 1, 2, 4; range from 3 to 21) add to the second-order factor ‘general irritation’ (GI), ranging from 7 to 56, with higher values indicating higher irritation (items see Table 1)5. The two-factorial structure of the scale was confirmed by Müller et al. using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis16 using latent variable modeling techniques with structural equation modeling as recommended by Rodriguez and Reise27. Müller et al. showed that a two-factorial model of the Irritation Scale showed a better fit to the data than a competing one-factorial model. The two-factorial structure was confirmed in a further study by Mohr et al.3 for nine language adaptions of the same scale.

We performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to analyze the dimensional structure of the theoretical model using the statistical package AMOS 2628. Since AMOS cannot consider case weights, we calculated the CFA with unweighted values (N = 1406). We analyzed three different models, using the Asymptotically Distribution-Free estimation procedure, due to the non-normally distributed data: A single-factor model where all items load on one general factor (GI), a two oblique factors solution where the respectively hypothesized items load on the two correlated latent factors CI and EI and a bifactorial model, where all items load on GI as well as the respectively hypothesized items on the two correlated latent factors CI and EI. Model fit was estimated with accepted fit indices Chi-square, CFI and RMSEA using the criteria suggested by Hu and Bentler29 who suggested values > .95 for CFI, and < 0.06 for RMSEA indicating a good fit. To compare the models, we calculated a Chi-square difference test using ∆Chi-square and ∆df, and looked at ∆CFI and ∆RMSEA. For ∆CFI a meaningful difference is assumed from < − 0.01 and for ∆RMSEA > 0.01530.

Psychometric instruments

Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ-4)

The Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety (PHQ-4) assesses depressive and anxious symptoms with four items on a scale from 0 (not affected at all) to 3 (affected almost every day) within the last two weeks18. Cronbach's alpha for this sample is 0.86.

Bodily Distress Syndrome 25 Checklist (BDS 25)

The Bodily Distress Syndrome 25 Checklist (BDS 25) uses 25 items on a scale of 0–4 to diagnose bodily distress syndrome, an overarching diagnosis proposed in 2010 for so-called functional somatic syndromes within the four categories of cardiopulmonary, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and general symptoms31. Cronbach's alpha is 0.93.

Somatic Symptom Scale-8 (SSS-8)

The Somatic Symptom Scale-8 (SSS-8) is a short form of the Patient Health Questionnaire PHQ-15 and measures impairment by eight different somatic symptoms within the past four weeks on four factors (gastrointestinal, pain, cardiopulmonary, and fatigue) on a scale of 0–432. Cronbach's alpha is 0.86.

Giessen Subjective Complaints List (GSC-8)

The Giessen Subjective Complaints List (GSC-8) assesses current complaints on a scale of 0–4 using eight different items that can be assigned to four factors: gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, fatigue, and cardiovascular complaints33. Cronbach's alpha is 0.89.

Comorbidity

The Comorbidity scale captures current impairment from 13 different health problems (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, cancer) using a dichotomous response format. It is part of the German version of the Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ-D)34. Cronbach's alpha of the reported sample is 0.80. For a comparison and discussion of somatic complaint scales see the work by Häuser et al.35.

Mini-ICF rating for activity and participation disorders in mental illness (Mini-ICF-APP-S)

The Mini-ICF rating for psychological activity and participation disorders in mental illness is used in the self-report version (Mini-ICF-APP-S)21,36. The assessment based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health ICF37 captures the subjective assessment of thirteen soft skills on a scale from 0 (‘This is clearly a strength of mine’) to 7 (‘I cannot do this at all’). In this work, the following dimensions are considered: (1) adjust to rules and routines, (2) plan and structure tasks, (3) be flexible, (4) apply knowledge, (5) make decisions, (6) be proactive, (7) be enduring, (8) be assertive, (8) interact with other persons, (10) integrate in groups, (11) build dyadic relationships, (12) self-care, and (13) move around27, which are combined into superordinate factors: cognitive and soft-skills (1–7), interactional skills (8–11) and basic skills (12, 13). Cronbach's alpha is 0.92.

Mobbing Intensity of Colleagues (MOB-C)

The Mobbing Intensity of Colleagues (MOB-C) scale consists of four items which ask about the subjective experience of workplace bullying on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree)23. Cronbach's alpha is 0.91.

Overcommitment scale (OC)

The Overcommitment scale (OC) is part of the Effort-Reward Imbalance scale (ERI) and measures the tendency to be overcommitted at work with six items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree)38. For the reported sample, Cronbach's alpha is 0.70.

General Self-efficacy in Easy Language (GSE-EL)

This questionnaire captures General Self-Efficacy in easy language (GSE-EL)39. The GSE-EL asks about optimistic competence expectations, i.e., the confidence in mastering difficult situations with the help of one's own competences39. Compared to the original scale from Jerusalem and Schwarzer40, the wording of the 10 items used here was simplified by Berger and colleagues39 and a dichotomous response format was chosen (0 = no; 1 = yes) and item six was rephrased. Cronbach's alpha is 0.84.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27. For the new normative values, the respective percentile rank values were calculated for the raw scale values of the two subscales EI and CI as well as for the GI. Pearson correlations were calculated for testing discriminant and convergent validity. If inferential tests are used, exact p values, effect sizes, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) are reported. Due to the size of the sample, parametric tests were calculated despite the lack of a normal distribution. Tests were performed two-sided at a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis of the individual IS items. All items show substantially positive skewness. For a positively skewed distribution most data falls to the right of the graph's peak41. A Shapiro Wilk test contradicts the assumption of normal distribution of the data. Internal consistency is considered very high with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92 for the GI, 0.89 for CI and 0.91 for EI. The correlation of the subscales EI and CI is r = 0.702, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.675; 0.727].

Factor analysis

An exploratory factor analysis confirmed the bifactorial structure of IS in our sample: 71.2% of the variance is explained by the first two factors (61.9% by factor 1 and 9.3% by factor 2). The oblimin-rotated factor matrix results in an assignment of the items to the two factors (items 1, 2 and 4 to factor 1, items 3, 5, 6, 7 and 8 to factor 2). The correlation of the factors is r = 0.664. To further examine the factor structure, we calculated a CFA testing a single-factor model, a two oblique factor model and a bifactor model. The model fit indices are presented in Table 2. The single factor model did not reach an overall good fit. The two-factor solution appeared to be superior compared to the single-factor model. However, the fit-indices of the two-factor model are contradictory. While the RMSEA indicate reasonable fit, the CFI indicate a rather poor fit, according to conventional cut-off criteria. The two latent factors CI and EI correlate with r = 0.828, the covariance sCIEI is 1.00, S.E. = 0.058. The two-factor model fits the data significantly better than the single factor model according to the Chi-square difference test (∆χ2 = 44.08, ∆df = 1, p < 0.001), as well as ∆CFI = − 0.11 and ∆RMSEA = 0.02. The bifactorial model did not converge.

The standardized parameter estimates of the single-factor and the two-factor solution are presented in Table 3. Overall, the factor loadings are consistently high.

New norms

Table 4 shows the raw scores with the corresponding percentile rank values for the two subscales and the overall index.

Table 5 presents the scale means and standard deviations for different age groups and both sexes.

Comparison to the existing norms

In Mohr, Müller et al.’s sample3, the mean GI score was 24.8 (sd = 9.7) for the total sample. In the sample presented here, the overall mean is 17.3 (sd = 8.9). An inferential test shows a significant difference of 7.5 (sd = 0.29), 95% CI [6.94; 8.07]: T(5,508) = 26, p < 0.001. In Mohr et al.'s sample, 1% of participants had an overall score of eight, which represents the lowest possible score on the IS, compared to 17.1% in the present data set.

IS and socio-demographic data

Higher education (university degree vs. other: T(1,475) = 5.50, p = < 0.001, d = 0.424; 95% CI [0.271; 0.573] for CI), former unemployment (yes vs. no: T(1,473) = 4.56, p < 0.001, d = 0.239; 95% CI [0.135; 0.341] for EI) and higher household income (up to 2499 € vs. over 3500 €) T(1,055) = − 2.91, p = 0.004, d = − 0.186; 95% CI[− 0.311; − 0.061] for CI) were significantly associated with higher irritation scores (for more detailed results see Table 6), although most effect sizes were small (cohen's d ~ 0.2). No differences were found with regard to sex and household size (living alone or with others).

Convergent and discriminant validity

Table 7 shows the correlations of the IS and its subscales with clinical indicators, like the PHQ-4, different somatic complaints and psychological functioning. All correlations are significant at p < 0.001 and show the expected direction with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.16 to 0.49. The z-values according to Dunn and Clark indicate whether the correlations between CI and EI with the respective scale differ significantly from each other42. For the PHQ-4 and the Mini-ICF-APP-S the correlations with the subscale EI are significantly higher than those with the subscale CI. For the somatic scales the calculated effect sizes indicate very small or no differences between EI and CI.

Table 8 shows the correlations with work related stressors and with individual ressources (self-efficacy). All correlations are significant at p < 0.001 and show the expected direction with correlation coefficients ranging from − 0.37 to 0.76. Z-Values according to Dunn and Clark42 show higher correlations of the scales with EI in comparison with CI for bullying and self-efficacy, although the effect sizes are small, and higher correlations of CI with OC.

Discussion

Our results suggest that the previous normative data of the IS6 may have overestimated the manifestations of irritation in the labour force. Compared with the previous data collected in 2005, the new normative data show a more positively skewed distribution with lower means. The sample used by Mohr, Müller et al. contains a large proportion (26.33%) of firefighters and police officers—a group with high job strain43,44,45. Moreover, one study which accounted for 17% of the sample was conducted in Eastern Germany at the time of German reunification, a period that brought many stressors and an increased risk of unemployment for residents of East Germany17. Thus, the lower means found in this representative sample presented here are plausible, and should provide a more accurate information on the level of irritation in the German labour force.

From a practical point of view, the higher mean values presented 2005 thus contributed to an underestimation of the average level of irritation in organizations. This deficiency has been corrected with the present new normative data. Our study allows for the first time reliable statements on the relationship between IS and important socio-demographic variables such as education, income, age and gender: The correlations with demographic characteristics indicate that higher education and higher income are related with higher levels of irritation, in particular with cognitive irritation. While high social status is often associated with better mental health46, it is also associated with more job responsibilities and stress47, which may explain the association with cognitive irritability.

In contrast to Mohr, Müller et al., we found no age differences with respect to CI. It is possible that the relationship between age and CI is moderated by type of employment and gender, as found by Rauschenbach et al.7, and in specific populations7.

Unemployment is generally associated with reduced health, including mental illness48,49,50. Accordingly, individuals in this sample who were previously unemployed show higher EI scores than individuals who were never unemployed. Even when employment continues again, the experience of unemployment seems to negatively affect health51.

Our findings largely confirm the assumption derived from the theory of goal discrepancy15 that EI represents a more severe impairment of well-being compared to CI. EI seems to capture more significant distress compared to CI because it captures the emotional strain and not only the mental preoccupation with work, which explains the stronger correlations with the other mental impairment scales (e.g. PHQ-4, Mini-ICF-APP-S, etc.). Perceived anger, nervousness and irritability (components of EI) are experienced rather physically, which could explain the higher correlations with the somatic scales with the EI compared to the CI. Causality cannot be assumed, but rather an interdependence of the components49,52.

The correlations with the assessed health indicators confirm overall the construct validity of the Irritation Scale. The GI as well as the subdimensions CI and EI correlate consistently with other indicators of mental well-being, functioning, and physical and mental health in the expected direction. Moreover, the experience of bullying as a main work stressor53,54 is also significantly positively related with higher levels of irritation.

We reviewed the factor structure of the IS scale using the available data. The findings of the factor analysis point to a two-factorial structure of the scale, although the fit of the two-factorial model in the CFA is slightly poorer, than that calculated by Müller et al.16, and shows contradictory fit. The two-factorial model should not be rejected because of its indices. Many authors prefer the use of fit indices for a differentiated consideration of possible model strengths and weaknesses55, or, in particular, for a comparison of models56, rather than simply applying strict cut-offs57,58. According to RMSEA the two-factorial model reasonably match the empirical data, though the CFI indicates an insufficient fit of the hypothesized model compared to a null model, i.e. a potential model with zero fit. A bifactorial model that would represent the theoretical assumptions of the irritation construct with one general factor and two underlying subfactors EI and CI did not converge, due to negative error covariances. Eid et al.59 reports that bifactorial models frequently result in improper solutions and misspecifications, because main assumptions of bifactorial models are often not met, i.e. uncorrelated first order factors, loadings of observed variables on first-order factors as well as the general factor. Post-hoc analyses indicate that the bifactorial model in our study can be specified if a loading on the GI is not allowed for some items. Improving the operationalization of the GI should therefore be the subject of further research.

Overall, the presented strong factor loadings and the plausible correlation patterns of the EI and CI subfactors with other constructs support the reasonable interpretation of the two subscales, although the CFA results suggest that the factor structure of the irritation scale requires further investigation. Unfortunately, we could not finally clarify with the performed CFA how the additional overall factor GI can be exactly operationalized. Therefore, its interpretation should be taken with caution.

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional study. No causality can be derived from the correlations with the other scales presented here. Moreover, apart from bullying, no further information on the job and working conditions was collected so that no further correlations with irritation can be examined.

Conclusion

The Irritation Scale (IS) is recommended for the asessment of work-related mental strain and is particularly valuable for the early detection of a potential deterioration of (mental) health. The present study corroborated the construct validity of the IS. With the new normative data presented here, an even more accurate classification of IS values in respect to the general German working population is possible. Underestimation of the average level of irritation in organisations can be avoided in the future.

Data availability

Preregistration of Studies and Analysis Plans: This study was not preregistered. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the following authors on reasonable request:: IS and OC: HG; GSE-EL: BS; MOB-C: JK; BDS 25 and SSS-8 and Comorbidity Scale: WH; GSC-8 and PHQ-4: EB; Mini-ICF-APP (in aggregate form): BM.

References

Walter, U., Plaumann, M., Dubben, S., Nöcker, G. & Kliche, T. Gesundheitsökonomische Evaluationen in der Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung. Pravention und Gesundheitsforderung 6, 94–101 (2011).

Tan, L. et al. Preventing the development of depression at work: A systematic review and meta-analysis of universal interventions in the workplace. BMC Med. 12, 1–11 (2014).

Mohr, G., Müller, A., Rigotti, T., Aycan, Z. & Tschan, F. The assessment of psychological strain in work contexts: Concerning the structural equivalency of nine language adaptations of the irritation scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 22, 198–206 (2006).

Mohr. Die Erfassung psychischer Befindensbeeinträchtigungen bei Industriearbeitern (Lang, 1986).

Mohr, G., Rigotti, T. & Müller, A. Irritation-Ein Instrument zur Erfassung psychischer Beanspruchung im Arbeitskontext. Skalen-und Itemparameter aus 15 Studien. Zeitschrift fur Arbeits- und Organ. 49, 44–48 (2005).

Mohr, G., Müller, A. & Rigotti, T. Normwerte der Skala Irritation: Zwei Dimensionen psychischer Beanspruchung. Diagnostica 51, 12–20 (2005).

Rauschenbach, C., Krumm, S., Thielgen, M. & Hertel, G. Age and work-related stress: A review and meta-analysis. J. Manag. Psychol. 28, 781–804 (2013).

Mohr, G. Fünf Subkonstrukte psychischer Befindensbeeinträchtigungen bei Industriearbeitern: Auswahl und Entwicklung. In Psychischer Stress am Arbeitsplatz 91–119 (S. Greif, E. Bamberg & N. Semmer, 1991).

Dormann, C. & Zapf, D. Social Stressors at work, irritation, and depressive symptoms: Accounting for unmeasured third variables in a multi-wave study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 75, 33–58 (2002).

Stück, M., Rigotti, T. & Mohr, G. Untersuchung der Wirksamkeit eines Belastungsbewältigungstrainings für den Lehrerberuf. Psychol. Erziehung und Unterr. 51, 234–242 (2004).

Altmann, T., Schönefeld, V. & Roth, M. Evaluation of an empathy training program to prevent emotional maladjustment symptoms in social professions. Psychology 06, 1893–1904 (2015).

Mulfinger, N. et al. Cluster-randomised trial evaluating a complex intervention to improve mental health and well-being of employees working in hospital—A protocol for the SEEGEN trial. BMC Public Health 19, 1–16 (2019).

Höge, T. When work strain transcends psychological boundaries: An inquiry into the relationship between time pressure, irritation, work-family conflict and psychosomatic complaints. Stress Health. 25, 41–51 (2009).

Warr, P. Logical and judgmental moderators of the criterion-related validity of personality scales. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 72, 187–204 (1999).

Klinger, E. Consequences of commitment to and disengagement from incentives. Psychol. Rev. 82, 1–25 (1975).

Müller, A., Mohr, G. & Rigotti, T. Differenzielle Aspekte psychischer Beanspruchung aus Sicht der Zielorientierung. Zeitschrift für Differ. und Diagnostische Psychol. 25, 213–225 (2004).

Garst, H., Frese, M. & Molenaar, P. C. M. The temporal factor of change in stressor-strain relationships: A growth curve model on a longitudinal study in East Germany. J. Appl. Psychol. 85, 417–438 (2000).

Löwe, B. et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 122, 86–95 (2010).

Regory, G. et al. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 1329–1335. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199910283411801 (1999).

Greer, T. L., Kurian, B. T. & Trivedi, M. H. Defining and measuring functional recovery from depression. CNS Drugs 2010(24), 267–284 (2010).

Linden, M., Keller, L., Noack, N. & Muschalla, B. Self-rating of capacity limitations in mental disorders: The Mini-ICF-APP-S. Behav. Med. Rehabil. Pract. 101, 14–22 (2018).

Theorell, T. et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 15, 1–14 (2015).

Pfaff, H., Bentz, J., Brähler, E. & Die, S. Mobbingintensität der Kolleginnen und Kollegen“ (MOB-K): Teststatistische Überprüfung an einer repräsentativen Bevölkerungsstichprobe. Psychosozial 109, 17–27 (2007).

Siegrist, J. Effort-reward imbalance at work and health. Hist. Curr. Perspect. Stress Health. 2, 261–291 (2002).

Schönfeld, P., Brailovskaia, J., Bieda, A., Zhang, X. C. & Margraf, J. The effects of daily stress on positive and negative mental health: Mediation through self-efficacy. Int. J. Clin. Health. Psychol. 16, 1–10 (2016).

Koch, A. ADM-Design und Einwohnermelderegister-Stichprobe. Stichproben bei mündlichen Bevoelkerungsumfragen [ADM Design and sampling based on residents’ register. Samples for population based face to face surveys]. In Stichproben in der Umfragepraxis (eds. Gabler, S. & Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J.) 99–116 (2000).

Rodriguez, A., Reise, S. P. & Haviland, M. G. Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and interpreting statistical indices. Psychol. Methods 21, 137–150 (2016).

Arbuckle, J. L. & Wothke, W. Amos 4.0. (1999).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55 (1999).

Chen, F. F. & Chen, F. F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 3, 464–504 (2007).

Schmalbach, B. et al. Validation of the German version of the Bodily Distress Syndrome 25 checklist in a representative German population sample. J. Psychosom. Res. 132, 109991 (2020).

Gierk, B. et al. The Somatic Symptom Scale-8 (SSS-8): A brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Intern. Med. 174, 399–407 (2014).

Kliem, S. et al. Brief assessment of subjective health complaints: Development, validation and population norms of a brief form of the Giessen Subjective Complaints List (GBB-8). J. Psychosom. Res. 95, 33–43 (2017).

Streibelt, M., Schmidt, C., Brünger, M. & Spyra, K. Komorbidität im Patientenurteil—Geht das?: Validität eines Instruments zur Selbsteinschätzung der Komorbidität (SCQ-D). Orthopäde 41, 303–310 (2012).

Häuser, W. et al. Prevalence and overlap of somatic symptom disorder, bodily distress syndrome and fibromyalgia syndrome in the German general population: A cross sectional study. J. Psychosom. Res. 133, 110111 (2020).

Linden, M. Disease and disability: The ICF model. Nervenarzt 86, 29–35 (2015).

WHO. International Statistical Classification and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) (World Health Organization, 2016).

Rödel, A., Siegrist, J., Hessel, A. & Brähler, E. Fragebogen zur Messung beruflicher Gratifikationskrisen. Zeitschrift für Differ. und Diagnostische Psychol. 25, 227–238 (2004).

Berger, U., Fehlinger, M., Mühleck, J., Wick, K. & Schwager, S. Inklusive Forschung: Validierung der Skala zur Allgemeinen Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung (SWE) in leichter Sprache. Psychother. Psychosom. Medizinische Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0831-2270 (2019).

Jerusalem, M. & Schwarzer, R. Skala zur Allgemeinen Selbstwirksamkeitserwartung. 1–4. http://www.selbstwirksam.de/ (1999).

Brys, G., Hubert, M. & Struyf, A. A comparison of some new measures of skewness BT—Developments in robust statistics. 98–113 (2003).

Dunn, O. J. & Clark, V. Correlation coefficients measured on the same individuals. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 66, 366 (1969).

Wagner, S. L., McFee, J. A. & Martin, C. A. Mental health implications of fire service membership. Traumatology (Tallahass Fla). 16, 26–32 (2010).

Wagner, S. L. et al. Systematic review of mental health symptoms in firefighters exposed to routine duty-related critical incidents. Traumatology (Tallahass. Fla). 27, 285–302 (2021).

Regehr, C., Hill, J., Knott, T. & Sault, B. Social support, self-efficacy and trauma in new recruits and experienced firefighters. Stress Health. 19, 189–193 (2003).

Tan, J. J. X., Kraus, M., Carpenter, N. & Adler, N. The association between objective and subjective socioeconomic standing and subjective well-being: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 146, 970–1020 (2020).

Hambrick, D. C., Finkelstein, S., Mooney, A. C., Finkelstein, S. & Mooney, A. N. N. C. Executive job demands: New insights for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 30, 472–491 (2005).

Herbig, B., Dragano, N. & Angerer, P. Health in the long-term unemployed. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 110, 413–419 (2013).

Roelfs, D. J., Shor, E., Davidson, K. W. & Schwartz, J. E. Losing life and livelihood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Soc. Sci. Med. 72, 840–854 (2011).

Zenger, M., Hinz, A., Petermann, F., Brähler, E. & Stöbel-Richter, Y. Gesundheit und Lebensqualität im Kontext von Arbeitslosigkeit und Sorgen um den Arbeitsplatz. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 63, 129–137 (2013).

Berth, H., Förster, P. & Brähler, E. Gesundheitsfolgen von Arbeitslosigkeit und Arbeitsplatzunsicherheit bei jungen Erwachsenen. Gesundheitswesen 65, 555–560 (2003).

Goodell, S., Druss, B. G. & Reisinger Walker, E. Mental disorders and medical comorbidity. Policy Br. (2011).

Nielsen, M. B., Indregard, A. M. R. & Øverland, S. Workplace bullying and sickness absence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the research literature. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health. 42, 359–370 (2016).

Verkuil, B., Atasayi, S. & Molendijk, M. L. Workplace bullying and mental health: A meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS ONE 10, 1–16 (2015).

Lai, K. & Green, S. B. The problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivariate Behav. Res. 51, 220–239 (2016).

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T. & Wen, Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct. Equ. Model. 11, 320–341 (2004).

Fan, X. & Sivo, S. A. Sensitivity of fit indices to model misspecification and model types. Multivariate Behav. Res. 42, 509–529 (2007).

McDonald, R. P. & Ho, M. H. R. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol. Methods 7, 64–82 (2002).

Eid, M., Geiser, C., Koch, T. & Heene, M. Anomalous results in G-factor models: Explanations and alternatives. Psychol. Methods 22, 541–562 (2017).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Survey implementation: E.B., Data provision: E.B., B.S., J.K., W.H., B.M., H.G., Data analysis: M.G., E.M.B., Manuscript draft: M.G., Manuscript modification and amendment: E.M.B., A.M. Manuscript review: M.S.G., H.G., A.M., E.B., W.H., J.K., B.M., T.R., B.S., E.M.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gralla, M.S., Guendel, H., Mueller, A. et al. Validation of the irritation scale on a representative German sample: new normative data. Sci Rep 13, 15374 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41829-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41829-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.