Abstract

In the current investigation, molecular dynamics (MD) and Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) simulation as remarkable and competent approaches have been employed for understanding structural and transport properties of MMMs in the realm of gas separation. The two commonly used polymers i.e. polysulfone (Psf) and polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as well as zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticle (NP) were used to carefully examine the transport properties of three light gasses (CO2, N2 and CH4) through simple Psf, Psf/PDMS composite loaded by different amounts of ZnO NP. Also, the fractional free volume (FFV), X-ray diffraction (XRD), glass transition temperature (Tg), and Equilibrium density were calculated to scrutinize the structural characterizations of the membranes. Moreover, the effect of feed pressure (4–16 bar) on gas separation performance of simulated MMMs was investigated. Results obtained in different experiments showed a clear improvement in the performance of simulated membranes by adding PDMS to PSf matrix. The selectivity of studied MMMs was in the range from 50.91 to 63.05 at pressures varying from 4 to 16 bar for the CO2/N2 gas pair, whereas the corresponding value for CO2/CH4 system was found to be in the range 27.27–46.24. For 6 wt% ZnO in 80%PSf + 20%PDMS membrane, high permeabilities of 78.02, 2.86 and 1.33 barrers were observed for CO2, CH4 and N2 gases, respectively. The 90%PSf + 10%PDMS membrane with 2% ZnO had a highest CO2/N2 selectivity value of 63.05 and its CO2 permeability at 8 bar was 57 barrer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most hazardous and prevalent greenhouse gas (GHG) that its accumulation in the environment drives global climate change1. Worldwide CO2 emissions have been projected to experience a sharp increase from 28,051 million metric tons (MMT) to about 42,325 MMT from 2005 to 20302. Besides, the global consumption of natural gas is projected to increase from 95 trillion cubic feet in 2003 to 182 trillion cubic feet in 20303,4. Beyond that, high levels of CO2 and Nitrogen (N2) gases were found as the major contaminants in the natural feed gas which must be reduced below 2–3% to meet pipeline specifications1,5. Additionally, CO2 lowers the calorific value of natural gas, and also causes severe corrosion problems in oil and gas pipelines as well as storage systems in the presence of water1,6,7. Therefore, purification and recovery of CO2 from flue gas are of great interest from the environmental and energy point of view. In this respect, using competent approaches, CO2 must be separated from natural gas before it enters the pipelines or released into the air.

The current conventional methods for the separation of CO2 from other gas molecules majorly encompass physical/chemical absorption, pressure swing adsorption, or cryogenic distillation8. Although, these conventional technologies have proven favorable separation performance, they still suffer from severe drawbacks such as low CO2 loading capacity, high equipment corrosion, high energy consumption4, high solution circulation rate and solution degradation, high capital costs for equipment, high circulation rate, high sulfur outlet content and undesired absorption of higher hydrocarbons with CO2 which results in hydrocarbon losses9,10. On the other hand, membranes as advanced technologies have been proven their promising role for gas separation. Simplicity of operation and installation, feasibility under mild conditions, smaller footprint and flexibility of operation due to compactness of modules with huge reduction in consumption of electricity and fuel, no need for extra agents and/or chemical, continuous mode of operation with partial or complete recycle of retentate/permeate, possibility of integration with other separation units to constitute effective hybrid processes for achieving improved economy and desired purity levels are some of the advantages of membrane separation processes8,11,12. Also, membranes can be “tailored” to adapt to a specific separation task3. Among the various kinds of membranes, polymeric membranes have received significant attention, mainly because they offer many desired properties such as excellent processing ability, low expense and high mechanical strength. Nevertheless, a limit in the trade-off between gas selectivity and permeability for these widely used membranes, has been identified as aptly shown by Robeson s “upper bound”13,14,15. Moreover, their poor thermal and chemical stability and the plasticization (related to CO2 concentration) also hamper the expansion of their province. Higher permeability and selectivity accompanied by good chemical and thermal resistance can be achieved by inorganic membranes such as zeolite16, mesoporous silica, carbon molecular sieve17, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)18,19, alumina20 and carbon nanotubes, but their fabrication is challenging and usually involves higher cost which thwarted their employment in large-scale industrial applications13,21,22. The constraint of both polymeric and inorganic membranes have in turn changed the concentration of researchers toward mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) which are fabricated by introducing inorganic particles at nanometer level into polymer matrix. They integrate the advantages of both excellent selectivity characteristic of inorganic materials and economical processing capabilities together with the acceptable mechanical properties of polymers21,23,24,25,26,27,28. In this regard, the preparation of high-quality MMMs with the ideal morphology has been greatly challenged by the formation of defects or voids in the membranes interfaces which is usually caused by poor compatibility of organic materials as fillers with the polymer matrix. This type of voids which are morphologically known as “sieve-in-a-cage” act as additional channels that allow non-selective gas transport; therefore the selectivity of the whole membrane reduces15,29,30,31. Hence, careful selection of both inorganic fillers and polymers is essential to attain a successful fabrication of MMM with acceptable gas separation performance. It is worth pointing that, different filler and polymer materials have been recently employed for the fabrication of MMMs in the realm of CO2/CH4 separation22,32,33.

The fabrication of new MMMs for a particular separation system by experiment measurements is laborious process and often awkward, time-consuming, and expensive. On the other hand, with the dramatic advances in mathematical algorithms using computational practices, simulation has appeared an effective tool in material science and engineering34,35,36,37,38,39. In this sense, in depth analyses of the microscopic mechanisms which affect membrane structures and properties quantitatively and qualitatively by computer simulation and use of molecular models and simulation techniques is requisite. Simulation at microscopic and mesoscopic level can offer detailed insight into the fundamentals of the membrane fabrication and its features. Insights given by simulation are valuable for the proper design of the separation, characterization, screening, and for the development of novel membranes with improved performance40.

In the last few decades, molecular simulation (MS) has been increasingly employed to predict the behavior of systems on an atomic scale with a reasonable degree of accuracy and reliability41,42,43. Besides, Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC)44 and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation methods have been widely utilized to obtain new insight on the transport behavior of gas molecules within polymeric membranes (i.e. MMMs) as well as considering various structural characteristics such as fractional free volume (FFV), glass transition temperature (Tg), radial distribution function (RDF), and X-ray diffraction (XRD), Wide-angle XRD (WAXD) of the system40,45,46,47. On this subject, Asghari et al.48 simulated the experiment results of a novel chitosan/silica MMMs filled with 10 wt% content of TEOS and APTEOS using MD and GCMC methods. The XRD test was accomplished to investigate the crystallinity of the simulated membranes in which the obtained results proved that membranes loaded with APTEOS indicated lower crystallinity compare to membranes with TEOS loading. To this end, the Tg of membranes containing APTEOS and TEOS was reported around 162 and 161 °C, respectively. In another study49, the influence of poly(ether block-6-amid) (PEBA) 1657 and zeolite 13× contents deposited onto a PSf/Polyethylene (PE) layer, on gas separation were evaluated. Both permeability and selectivity values of simulated membranes were examined using N2, CO2 and CH4 gas molecules. It was reported that, having coated a PDMS skin layer on the surface of PEBA-zeolite PSf/PE MMM resulted in 153% and 18.24% increase in CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 selectivity, respectively. Also, they50 studied the effect of nanomaterials shape (nanorod and nanosphere) on gas separation performance by simulating PEBA 1657/ZnO MMMs. Beyond that, structural properties were measured by applying FFV and WAXD analyses. In another study, Golzar et al.51 investigated the transport properties CO2, CH4, N2, and O2 gas molecules through MMMs using MD and GCMC methods. Pristine and functionalized single wall carbon nanotube and multi wall carbon nanotube were embedded into the pure PIM-1 to study the CNT dispersion in the polymer matrix and its performance improvement. Also, the same authors52 studied the separation process of acid gas molecules such as H2S and CO2 from N2 and CH4 using simple polymeric membranes including PEBA-1657, poly (acrylonitrile) (PAN) and poly (trimethylsilyl) propyne (PTMSP) and zeolitic imidazole framework (ZIF) with various nanofiller loading in which both MD and GCMC simulation methods were applied. It was reported that, the MMMs incorporated with 2 wt% of the functionalized CNT particles indicated better performance for the CO2 separation compare to other simulated membranes. In order to consider the transport properties of simple PEBA polymer, simple Psf polymer, and PEBA/Psf composites loaded by ZIF-90 particles, three different gas molecules (CO2, CH4 and N2) were hired53. It was proved that Psf addition to PEBA polymer matrix, resulted in significant increase in the selectivity of CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 gases. Meanwhile, loading ZIF-90 particles into the polymer matrix led to an upward trend for gas permeability of PEBA/Psf composites. Thus, the nanomaterials content loaded in polymer matrix, type of polymer and nano content, the process of membrane preparation, operating temperature and pressure, and the utilized solvents and anti-solvents are the most influential factors on the performance of membranes in the realm of gas separation.

In current study, eight different MMMs composed of blended PDMS/Psf polymers loaded with ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) as fillers have been simulated to scrutinize structural and transport properties of this novel kind of MMMs. Transport properties of three different gas molecules (CO2, CH4 and N2) through the simulated MMMs have been well investigated and discussed. Herein, surface topography, morphology, sorption and diffusion of gas molecules, the membrane crystallinity, and other structural and transport properties of this MMM have been studied. Furthermore, all the simulation results have been extracted and compared with experimental result to examine the reliability of current simulation which is proven that both results are consistent in approach.

Simulation theory

Force field

A force field consists of a series of potential functions and numerical parameters to explain the interaction potential. In the past, a number of these power fields have been developed for a variety of systems. For example, the force field of the Molecular Mechanics (MM) force field can be used for organic compounds, free radicals, and ions54. Another force field called AMBER is suitable for proteins, nucleic acids and polysaccharides55. Moreover, there are some promising, comprehensive and more complicated force fields which can be used to measure complex properties of materials like molecular structure, spectrum, and adaptations. These parameters have been obtained using a combination of mechanical quantum computing and laboratory data. PCFF, CVFF, Deriding, Universal, and COMPASS are the main and the most commonly used force field. In present article, the COMPASS force field has been utilized not just because of covering all the molecular interactions, but because COMPASS is a promising force field that supports atomistic simulations of condensed phase materials and represent the state-of-the-art force field technology56. COMPASS force field is able to predict the properties of a broad range of systems with high accuracy. Its main aim is to estimate the molecular properties, with an accuracy comparable with experiment44.

Materials used

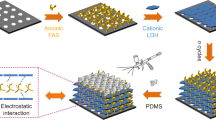

The investigation utilized molecular dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo simulation techniques to create mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) using Polysulfone (PSF), Polydimethyl Siloxane (PDMS), and zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles.

PDMS is a rubbery polymer with exceptional gas permeability, super hydrophobic properties, and excellent mechanical and chemical stability57,58. PSF is a glassy polymer that performs well in separating CO259. ZnO is a common nanoparticle with attractive attributes such as low cost, good chemical, electrical, and mechanical properties, and a high surface-to-volume ratio compared to other nanoparticles60. ZnO nanoparticles are also a great option for CO2 adsorption due to their inherent affinity61,62,63.

Theory and simulation procedure

Combination of significant properties of NPs with the natural features of polymers undoubtedly improves the physical and transport properties of novel MMMs64. In present article, the gas transport behavior of PSf polymer blended with PDMS, and loaded with ZnO NPs has been investigated It is worth pointing that, solution-diffusion is the dominant mechanism of dense membranes regarding the transport behavior and associated diffusion and solubility coefficients56,65. Different parameters such as the interactions of polymer-gas molecules, gas–gas has much of a role to play in altering diffusivity and solubility coefficients. The permeability and selectivity values can be calculated by Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

where \({D}\) is the diffusivity coefficient, \(S\) is the solubility coefficient and \({\alpha }_{A/B}\) is the selectivity of gas A/B64,66,67. Generally, the selectivity can be defined as the permeability of one component over the other one which literally indicates the competence of each gas molecules.

Regarding the simulation process, Materials Studio software package from Accerlys Inc version 6.0 and COMPASS II force field was utilized to construct raw materials and conduct all the simulation steps. GCMC and MD are the two most oftenly utilized methods to determine the solubility and diffusivity coefficients, respectively. Various MMMs were simulated using different weight percent of PSf, PDMS and ZnO NPs. Some analysis like FFV, Tg, and XRD have been applied to determine the structural features and properties of the constructed membranes. Adsorption isotherms and Mean Square Displacement (MSD) graphs were additionally utilized to estimate both solubility and diffusivity coefficients, respectively. To this end, the present molecular simulation study (at microscopic level) prognosticated the gas separation properties of all constructed MMMs.

MMM construction

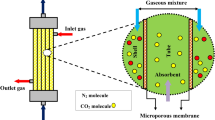

The periodic cells were simulated employing PSf and PDMS polymers chain with 10 chain length. Clearly, 10 and 20 wt% of PDMS was blended with PSf polymer to evaluate the effect of polymer blending. Additionally, the simulated cells were cubic in shape and sized between 30–40 Å, depending on the amount of materials loaded. The blended polymers were loaded by 2, 4 and 6 wt% of ZnO NPs. Hence, various MMMs were simulated. The ZnO NP was constructed in a 5 Å cubic form. Figure 1 indicates the periodic cells and raw materials68. Constructed materials, polymer chains and NP were also optimized from the energy and geometry perspective. It was chosen for the amorphous module to create 5 output frames; whereas 0.7 g cm−3 (at 298 K) was the selected value for the initial density. Finally, the obtained amorphous cells blended by 10 and 20 wt% of PDMS and dissimilar ZnO loading were acquired. Table 1 indicates the 9 different simulated membranes and their appointed names.

Forcite module was applied to optimize the simulated membranes. The non-equilibrium energy was eliminated by choosing smart method for better convergence. The obtained configurations were considered and the one showing the lowest level of energy was selected. The annealed procedure performing in the range of 298 and 500 k at a 5-cycle process was applied in an NPT run. Then, a 4000 ps-NPT run was implemented over the selected configuration to attain the final and experimental density. Additionally, in order to equilibrate the membrane structure with the experimental density, a 1000 ps-NVT run was conducted. Simultaneously, all gas molecules were simulated and then optimized by Forcite module. All the experiments were conducted at 298 K. Additionally, in order to control the temperature at the designated heating temperature and pressure of 1 atm, the simulation utilized the Nose thermostat with a Q ratio of 0.01 and the Berendsen barostat with a decay constant of 0.1 ps. Herein, the COMPASS II force field, along with atom-based electrostatic and van der Waals summation methods were selected with a fine cutoff distance of 12.5 Å. Figure 1 demonstrate the final configurations of optimized MMMs.

Results and discussion

Simulation methods

Fractional free volume (FFV)

The FFVs of simulated periodic cells as a membrane have been deliberated using spherical probe with Connolly radius of 0 nm. FFV values can be calculated by Eq. (3) as follows:49,56,69,70.

where Vw and Vs are van de Waals and specific volumes, respectively. It is worth pointing that, the polymer chains’ occupied volume is usually 1.3 times greater than their van der Waals volume.

With reference to the results summarized in Table 2, incorporation of PDMS and ZnO NP into the membrane matrix resulted in higher FFV. Also, 80%PSf + 20%PDMS membrane loaded with 6 wt% ZnO indicated the highest FFV value. Moreover, FFV value increased from 17.1 to 20.8 because of more NP content introduced into the polymer matrix for PSf and 80%PSf + 20%PDMS, respectively. In general run of things, more nanomaterial loading more voids creation between polymer chains which takes place with greater d-spacing values. The special structure of ZnO undoubtedly enhanced the polymer chain distances and caused more fractional volume in polymer matrix. According to the FFV results, the effect of ZnO loading in PSf membrane matrix is obvious which follows an increasing trend starting from 17.01 to 20.1. The resulted FFV data are summarized in Table 2.

Glass transition temperature (Tg)

Tg is a transition temperature that estimates the change in material state from a glassy state to a rubbery state that happens in amorphous polymers. As Fig. 2 indicates, the Tg of the constructed MMMs has displayed an increasing trend with ZnO loading. Also, the effect of loading 10 and 20 wt% of PDMS into the PSf polymer matrix is considerable. Which proves the resulted polymers stemming from combination of PSf and PDMS loaded ZnO tend to higher Tg values. The glassy temperature of polymer blends can be calculated from Fox equation as below56,71,72,73,74,75,76:

Here \({T}_{g-mix}\) and \({T}_{g-i}\) are the Tg of the mixture/copolymer and of the components, respectively, and \({\omega }_{i}\) is the mass fraction of component i. It was observed that increase in ZnO content made slight changes in Tg, which support the suggestion of no evident interaction between PDMS and ZnO NPs. In this subject, this happening can be attributed to the limited movement of the polymer backbone arising from PSF/PDMS–ZnO interactions. Figure 2 shows the calculated Tg for all simulated membranes.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

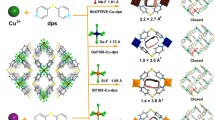

As can be seen in Fig. 3 presenting the scattering diffraction patterns of the MMM, the maximum peaks are usually considered more significant than other patterns because of the possibility of calculating the d-spacing values based on Bragg’s equation \(\left(d=\frac{\lambda }{2} {\text{sin}}\theta \right)\). This equation explains the intersegmental distances between polymer back bones68,77. By comparing the XRD patterns of simulated membranes, it can be concluded that the main peak of each sample is 2θ = 15°–20° and with increment of ZnO content, the main peak gets sharper and mainly locates in lower 2θ. For instance, the value of 2θ of pure PSf is around 17.00 ± 0.5%, while by adding 2 wt% of ZnO to the matrix, this value changes significantly and gets sharper. The presence of ZnO in PSf results in the expansion of the distance among PSf chains, and this fact has been shown by comparing d-spacing of each membrane. D-spacing of simple PSf is reported as 4.74 Å. Also, the d-spacing of 80%PSf + 20%PDMS, 80%PSf + 20%PDMS/2%ZnO, 80%PSf + 20%PDMS/4%ZnO and 80%PSf + 20%PDMS/6% ZnO are reported as 4.85 Å, 5.04 Å, 5.27 Å, and 5.46 Å, respectively. Wang et al.78 calculated d-spacing of pure PSf membrane about 5.2 Å. In another study, Golzar et al.77 indicated that its d-spacing was around 4.98 Å. Overall, this value is comparable to the simulated results of current study which both show consistency in approach.

Density

In current molecular simulation study, after selecting the density with initial value of 0.7 g cm−3, the process of constructing MMMs was applied. Also, Fig. 4 indicates the density graph of 80%PSf + 20%PDMS membranes loaded by 2, 4, and 6 wt% ZnO at 4, 8, 12 and 16 bar. It was observed that, the number of loaded PSf, PDMS chains and the amount of ZnO NPs in the polymer matrix directly effect of the density values of simulated membranes with various and different length as Table 3 summarized the acquired average densities of simulated membranes. It is noteworthy that, NPT runs have been applied to attain the actual density of each system which definitely modifies the density and dimensions of each cell. Consequently, the density of cells started to increase by a considerable reduction in cell length. Figure 4 indicates that the membrane density increased along with run time, whereas after 2000 ps a plateau was reached for the rest of the operating time. Therefore, the adequacy of the 4000 ps-NPT run was confirmed for reaching the equilibrium state.

Mean square displacement (MSD)

Based on the Verlet algorithm, the motion equations with 1 fs time step was employed as a promising approach to ensure the energy conservation as well as predicting the self-diffusion coefficient \(({D}_{i})\). Equation (5) under the name of the Einstein equation indicates the calculation of the self-diffusivity of component \((i)\):

Based on Eq. (5), CO2, N2 and CH4 gases start penetrating within the membrane relying on the diffusion mechanism happening in a pico-second. It is worth to note that, this motion relation is proportional to \({t}^{x}\) function when the initial condition (x < 1) applies79. To calculate \({D}_{i}\) of all gases in simple PSf and all MMMs, three different gas molecules (CO2, N2, CH4) with optimized geometries and minimized energies were inserted into the simulated membrane. The final configurations indicated the minimum energy. Then, the MSD results were evaluated and consequently the \({D}_{i}\) was calculated. These data were the results of three consecutive experiments as an average which were reported in Table 4. By taking a look at Table 4, it becomes obvious that the \({D}_{i}\) of gas molecules within the constructed membranes increases by higher loading of ZnO stemming from higher FFV and more free paths for gas diffusion. The same trend was observed for loading 10 and then 20 wt% of PDMS. To make sure that the MD simulation results are reliable, Fig. 5 revealed that the slope of Log (MSD) vs. Log (time) tend to reach unit80. As can be seen in this figure, the amount of MSD for CO2 gas is higher than N2 and CH4, respectively, because of the linear structure of this gas which accelerates and increases the transfer diffusion through the MMMs compare to methane, which has a Tetrahedron structure.

MSD of CO2, N2, CH4, gases at 298 K and 4 bar pressure within: (a) 90% PSf + 10% PDMS, (b) 90% PSf + 10% PDMS/2% ZnO, (c) 90% PSf + 10% PDMS/4% ZnO, (d) 90% PSf + 10% PDMS/6% ZnO, (e) 80% PSf + 20% PDMS, (f) 80% PSf + 20% PDMS/2% ZnO, (g) 80% PSf + 20% PDMS/4% ZnO, and (h) 80% PSf + 20% PDMS/6% ZnO.

Solubility coefficients

To calculate the solubility coefficient of each gas molecules within the simulated simple PSf and MMMs, GCMC was hired including the Metropolis method as a reliable task in Sorption module. Besides, adsorption isotherms is another task that can evaluate the effect of some experimental condition such as pressure and temperature on the solubility coefficient. Additionally, one of the other advantages of GCMC method is reaching to a better understanding of the sorption mechanism at the atomistic level. This sorption mechanism can be included some values such as regrowth, conformer rotation, translation and exchange. Notwithstanding, the Metropolis task involves a number of moves just like translation, rotation and exchange. Equation (6) indicates the acceptance probability as follows:

where, \({U}_{(n)}\), \({U}_{(o)}\) and \({k}_{B}\) are the potential energy of old state, the potential energy of new state, and Boltzmann's constant, respectively81,82.

Generally, GCMC method works based on the trial insertion and deletion of molecules, in which, 105 equilibrium steps and 106 production steps44 were set to conduct the adsorption isotherm calculations. Equation (7) shows the probability of rejecting or accepting a new location for any gas as follows:

where \(\Delta E\), \({f}_{i}\),\({N}_{i}\), and \(V\) can be defined as the difference of Van der Waals interaction and columbic interaction for two configurations, the fugacity, the number of molecules for component i, and the volume of amorphous cell, respectively68,83. To measure the solubility coefficient, the slope of adsorption isotherms represents was measured as Eq. (8) indicates65,84:

where \(P\) is the fugacity and \(C\) represents the gas concentration. Figure 6 indicates the adsorption isotherm diagrams for all diffusing molecules across the simulated membranes.

Generally, various factors can directly affect on gas permeation such as FFV, crystallinity, pressure, temperature, and so on. In current simulation study, the structural features and separation properties of constructed membranes have been affected by different factors from different aspects. Inevitably, some of them had negative impact on gas separation performance while some others positively enhanced its performance. Therefore, the summation of all these positive and negative effects lead to a certain value for gas permeability. So, evaluating all these factors can be of great help to reach a better understand of the system.

As it is obvious in Table 5, CO2 solubility within the membranes is much greater than CH4 and N2. The main reason may be attributed to the fact that CO2 is an acid gas and PSf shows better affiliation with CO2. Also, Table 5 shows that, the solubility coefficients of pure gases through the membranes generally enhance with more ZnO content, which indicates the effect of presence of ZnO NPs in polymer matrix. Also, these figures experience an upward trend when the PDMS content increases. Although, the Tg experiences a slight increase, higher solubility coefficients convey this meaning that the membranes confronted with expanded amorphous region which provided the polymer matrix with a higher chance of adsorbing more gas molecules. To clarify, the increasing trend of measured slopes regarding the adsorption isotherms proves the gradual increase of the solubility coefficients of utilized gas molecules. On the other side, the acquired results of MSD analysis revealed that the diffusivity coefficients of each gas molecules experienced a gradual increase due to the presence of PDMS polymer chains and more pore and channels of created by ZnO NPs. According to the conducted experiments, the results of gas permeability have been evaluated exhaustively in the next section.

Gas permeability and perm-selectivity

In general, the permeability can be explained as the multiplication of solubility and diffusivity coefficients. In this section, the permeability of three pure gas molecules were calculated to thoroughly investigate the performance of simulated membranes. In this regard, two loadings of PDMS and 4 different loading of ZnO NPs have been incorporated into the PSf matrix. So, it can be perceived that NPs loading is another influential factor affecting the gas permeability.

Notably, as mentioned before all raw materials have been optimized geometrically and minimized in aspect of energy level. Also, all simulation practices were performed at thermodynamic equilibrium state. A 1000-ps NVT and 4000-ps NPT MD runs were conducted to eliminate the non-equilibrium states and reach the final density. It should be noted that, Nose–Hoover thermostat was chosen as the temperature controller these MD runs.

All three gas molecules were inserted into the simulated MMM to measure the \({D}_{i}\). This coefficient can be calculated as the slope of MSD graph. The reason that validates the obtained results is that the slope of Log (MSD) vs. Log (time) diagram for all gases unify85. On the other side, having used the GCMC method, the solubility coefficients of all gas molecules were computed. Figure 7 illustrates the effect of ZnO loading on gas permeability through simple PSf membrane.

As can be seen from Fig. 7, CO2 showed the highest permeability over two other gases. CH4 permeability is considerably greater than N2 permeability. Besides, it is obvious that, loading more ZnO content led to greater permeabilities of all gasses. The other simulated MMMs were tested by gas permeability and the effect of ZnO loading and PDMS blending were considered. Figure 8 indicates clearly the effect of these parameters. A brief look at Fig. 8 indicates that adding more ZnO content due to providing higher d-spacing and expanded distances between polymer chains generally leads to higher permeability values. Although, the effect of NPs is considerable, in some cases loading 6 wt% of ZnO resulted in lower permeability compare to 4 wt% which may stem from agglomeration of NPs playing a negative role against permeability. Additionally, by applying more operational pressure (4, 8, 12, and 16 bar), permeability of all three gases increases71. On the other side, the perm-selectivity of membranes are listed in Table 6. It is clear that ZnO loading negatively effects on CO2/CH4 selectivity, while PDMS blending increases its selectivity. Besides, CO2/N2 selectivity followed the same trend in both ZnO loading and PDMS blending.

The before mentioned trends can be attributed to the ZnO nature and structure which tends to let all the three gases pass freely within the membrane. Also, the PDMS blending enhanced the MMMs performance resulted in better gas separation. The increasing feed pressure was considered as a positive effect on perm-selectivity which moderately changed their performance. The results obtained from simulation study were compared with the experiments for the perm-selectivity within PSF/PDMS composite membrane, without ZnO NPs86. It was concluded that both simulation and experimental results are in good agreement.

Comparison with the literature

The effectiveness of MMMs for technical uses is determined by two primary factors: selectivity and permeability. In this study, the selectivity of gas pairs was compared to outcomes from earlier research and the compiled information is listed in Table 7 with corresponding references. The results indicate that the MMMs developed in this investigation have superior selectivity values for CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separation compared to previously studied membranes. The PSf/PDMS–Nano ZnO MMM exhibited significant potential for industrial applications such as natural gas sweetening or biogas purification and warrants further exploration.

Robeson’s upper bound

The gas separation performance of simulated periodic cells were examined by Robeson’s upper bound14 which is plotted for the selectivity vs. permeability of gas pairs of N2, CH4, and CO2. This plot indicates the acquired data based on the selectivity vs. permeability of the simulated membranes. What perceived from this plot is that which membranes demonstrated more appropriate separation performance compare to the industry standards68,56. In other words, closer points to the Robeson’s upper bound proclaim that those points associated with membrane have better separation performance. Figure 9 indicates the Robeson’s Upper Bound for CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 at 4 and 16 bar. A brief look at the Fig. 9 shows that the simulated membranes had better CO2/N2 separation performance than CO2/CH4. This result is attributed to the fact that, CH4 showed double as the N2 permeability. Moreover, the membranes loaded by 4% wt% of ZnO had better performance than others in which 20 wt% PDMS blended membrane were moderately better than 10 wt. % blended ones.

Conclusion

The permeability of some pure gas molecules (e.g., CO2, N2 and CH4) within sveral suggested MMMs were predicted using molecular simulation methods. In this regard, Psf polymer matrix was loaded by various content of ZnO NPs and blended 10 and 20 wt% of PDMS. Also, their performance was evaluated using MS by some structural and transport analysis. Tg and FFV results illustrated that the loading ZnO NPs directly influenced the membrane matrix, which led to different gas permeability. Blending 10 and then 20 wt% PDMS clearly improved the membrane performance. In other words, higher perm-selectivity was achieved by more blended polymer. ZnO loading resulted in higher Tg and more rigid sections. However, it improved the FFV values. It was shown that the more pressure applied, the more permeability and selectivity values resulted. The Tg of the simulated MMMs experienced an increasing trend with increasing ZnO content, indicating that MMMs had more extended rigid region than unfilled membranes. The fact that the slopes of adsorption isotherms experienced an increasing trend proved that that the solubility coefficients of employed gas molecules soared gradually. With reference to the MSD analysis, it was obvious that \({D}_{i}\) of gas molecules changed gently because of higher pore and channels, higher pressure, the ZnO content. In conclusion, this simulation study reveals that, the PSf/PDMS polymer matrix membrane incorporated with ZnO NPs might be a fascinating MMM for separation of CO2/CH4/N2 mixtures in gas refineries plants.

The transferability of a simulation method used in a study to other mixed matrix membranes for gas separation depends on several factors, such as the molecular interactions between the gas molecules and the membrane material, as well as the structural properties of the membrane. In general, the transferability of a simulation method can be improved if the method has been validated using experimental data and if it accounts for the specific properties of the membrane material, such as pore size, surface area, and surface chemistry. Additionally, the simulation method should be able to capture the dynamic behavior of the gas molecules within the membrane, including adsorption and desorption processes, as well as diffusion and transport. However, it is important to note that even with a well-validated simulation method, the transferability of the results to other mixed matrix membranes may be limited due to the differences in the composition and structure of the membranes. Therefore, it is recommended to validate the simulation method for each specific membrane material and to account for any differences in the properties of the membrane when interpreting the results. Therefore, the results obtained in current article have been compared with experimental results as discussed in previous sections.

Finally, MS can be considered as a prospective and profitable tool to not only estimate the structural features and separation properties of polymeric structures but also to optimize the operating factors which undoubtedly enhance the membrane separation performance relying on their promising features.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Venna, S. R. & Carreon, M. A. Amino-functionalized SAPO-34 membranes for CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separation. Langmuir 27, 2888–2894 (2011).

Venna, S. R. & Carreon, M. A. Highly permeable zeolite imidazolate framework-8 membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 76–78 (2010).

Yeo, Z. Y., Chew, T. L., Zhu, P. W., Mohamed, A. R. & Chai, S.-P. Conventional processes and membrane technology for carbon dioxide removal from natural gas: A review. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 21, 282–298 (2012).

Liu, K., Song, C. & Subramani, V. Hydrogen and Syngas Production and Purification Technologies (Wiley, 2010).

Mubashir, M., Fong, Y. Y., Keong, L. K. & Sharrif, M. A. B. Synthesis and performance of deca-dodecasil 3 rhombohedral (ddr)-type zeolite membrane in CO2 separation—A review. ASEAN J. Chem. Eng. 14, 48–57 (2015).

Baker, R. W. Future directions of membrane gas separation technology. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 41, 1393–1411 (2002).

Mubashir, M. et al. Effect of process parameters over carbon-based ZIF-62 nano-rooted membrane for environmental pollutants separation. Chemosphere 291, 133006 (2022).

Sanders, D. F. et al. Energy-efficient polymeric gas separation membranes for a sustainable future: A review. Polymer 54, 4729–4761 (2013).

Olajire, A. A. CO2 capture and separation technologies for end-of-pipe applications—A review. Energy 35, 2610–2628 (2010).

Sayari, A., Belmabkhout, Y. & Serna-Guerrero, R. Flue gas treatment via CO2 adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 171, 760–774 (2011).

Thür, R. et al. Bipyridine-based UiO-67 as novel filler in mixed-matrix membranes for CO2-selective gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 576, 78–87 (2019).

Karbasi, E. et al. Experimental and numerical study of air-gap membrane distillation (AGMD): Novel AGMD module for Oxygen-18 stable isotope enrichment. Chem. Eng. J. 322, 667–678 (2017).

Basu, S., Khan, A. L., Cano-Odena, A., Liu, C. & Vankelecom, I. F. Membrane-based technologies for biogas separations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 750–768 (2010).

Robeson, L. M. Correlation of separation factor versus permeability for polymeric membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 62, 165–185 (1991).

Robeson, L. M. The upper bound revisited. J. Membr. Sci. 320, 390–400 (2008).

Tavolaro, A. & Drioli, E. Zeolite membranes. Adv. Mater. 11, 975–996 (1999).

Hägg, M. B., Lie, J. A. & Lindbråthen, A. Carbon molecular sieve membranes: A promising alternative for selected industrial applications. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 984, 329–345 (2003).

Li, Y. S. et al. Molecular sieve membrane: Supported metal–organic framework with high hydrogen selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 548–551 (2010).

Shah, M., McCarthy, M. C., Sachdeva, S., Lee, A. K. & Jeong, H.-K. Current status of metal–organic framework membranes for gas separations: Promises and challenges. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 2179–2199 (2012).

Leenaars, A., Keizer, K. & Burggraaf, A. The preparation and characterization of alumina membranes with ultra-fine pores. J. Mater. Sci. 19, 1077–1088 (1984).

Chung, T.-S., Jiang, L. Y., Li, Y. & Kulprathipanja, S. Mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) comprising organic polymers with dispersed inorganic fillers for gas separation. Prog. Polym. Sci. 32, 483–507 (2007).

Li, W., Chuah, C. Y., Nie, L. & Bae, T.-H. Enhanced CO2/CH4 selectivity and mechanical strength of mixed-matrix membrane incorporated with NiDOBDC/GO composite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 74, 118–125 (2019).

Aroon, M., Ismail, A., Matsuura, T. & Montazer-Rahmati, M. Performance studies of mixed matrix membranes for gas separation: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 75, 229–242 (2010).

Dong, G., Li, H. & Chen, V. Challenges and opportunities for mixed-matrix membranes for gas separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 4610–4630 (2013).

Goh, P., Ismail, A., Sanip, S., Ng, B. & Aziz, M. Recent advances of inorganic fillers in mixed matrix membrane for gas separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 81, 243–264 (2011).

Mitra, T., Bhavsar, R. S., Adams, D. J., Budd, P. M. & Cooper, A. I. PIM-1 mixed matrix membranes for gas separations using cost-effective hypercrosslinked nanoparticle fillers. Chem. Commun. 52, 5581–5584 (2016).

Rezakazemi, M., Amooghin, A. E., Montazer-Rahmati, M. M., Ismail, A. F. & Matsuura, T. State-of-the-art membrane based CO2 separation using mixed matrix membranes (MMMs): An overview on current status and future directions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 39, 817–861 (2014).

Seoane, B. et al. Metal–organic framework based mixed matrix membranes: A solution for highly efficient CO 2 capture? Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2421–2454 (2015).

Moore, T. T. & Koros, W. J. Non-ideal effects in organic–inorganic materials for gas separation membranes. J. Mol. Struct. 739, 87–98 (2005).

Noble, R. D. Perspectives on mixed matrix membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 378, 393–397 (2011).

Vinh-Thang, H. & Kaliaguine, S. Predictive models for mixed-matrix membrane performance: A review. Chem. Rev. 113, 4980–5028 (2013).

Nematollahi, M. H., Dehaghani, A. H. S. & Abedini, R. CO2/CH4 separation with poly (4-methyl-1-pentyne)(TPX) based mixed matrix membrane filled with Al2 O3 nanoparticles. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 33, 657–665 (2016).

Saeedi Dehaghani, A. H. & Pirouzfar, V. Preparation of high-performance membranes derived from poly (4-methyl-1-pentene)/zinc oxide particles. Chem. Eng. Technol. 40, 1693–1701 (2017).

Vaferi, B., Rahnama, Y., Darvishi, P., Toorani, A. & Lashkarbolooki, M. Phase equilibria modeling of binary systems containing ethanol using optimal feedforward neural network. J. Supercrit. Fluids 84, 80–88 (2013).

Vaferi, B., Gitifar, V., Darvishi, P. & Mowla, D. Modeling and analysis of effective thermal conductivity of sandstone at high pressure and temperature using optimal artificial neural networks. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 119, 69–78 (2014).

Moayedi, H., Aghel, B., Vaferi, B., Foong, L. K. & Bui, D. T. The feasibility of Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm combined with imperialist competitive computational method predicting drag reduction in crude oil pipelines. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 185, 106634 (2020).

Khalifeh, A. & Vaferi, B. Intelligent assessment of effect of aggregation on thermal conductivity of nanofluids—Comparison by experimental data and empirical correlations. Thermochim. Acta 681, 178377 (2019).

Amini, Y. & NasrEsfahany, M. CFD simulation of the structured packings: A review. Sep. Sci. Technol. 54, 2536–2554 (2019).

Amini, Y., Gerdroodbary, M. B., Pishvaie, M. R., Moradi, R. & Monfared, S. M. Optimal control of batch cooling crystallizers by using genetic algorithm. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 8, 300–310 (2016).

Dehghani, M., Asghari, M., Ismail, A. F. & Mohammadi, A. H. Molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation of the structural properties, diffusion and adsorption of poly (amide-6-b-ethylene oxide)/Faujasite mixed matrix membranes. J. Mol. Liq. 242, 404–415 (2017).

Bernardo, P., Drioli, E. & Golemme, G. Membrane gas separation: A review/state of the art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 48, 4638–4663 (2009).

Yang, Q., Xue, C., Zhong, C. & Chen, J. F. Molecular simulation of separation of CO2 from flue gases in CU-BTC metal–organic framework. AIChE J. 53, 2832–2840 (2007).

Yang, Q. & Zhong, C. Molecular simulation of carbon dioxide/methane/hydrogen mixture adsorption in metal–organic frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 17776–17783 (2006).

Harami, H. R., Fini, F. R., Rezakazemi, M. & Shirazian, S. Sorption in mixed matrix membranes: Experimental and molecular dynamic simulation and grand canonical Monte Carlo method. J. Mol. Liq. 282, 566–576 (2019).

Han, J., Gee, R. H. & Boyd, R. H. Glass transition temperatures of polymers from molecular dynamics simulations. Macromolecules 27, 7781–7784 (1994).

Tocci, E., Hofmann, D., Paul, D., Russo, N. & Drioli, E. A molecular simulation study on gas diffusion in a dense poly (ether–ether–ketone) membrane. Polymer 42, 521–533 (2001).

Torres, J., Nealey, P. & De Pablo, J. Molecular simulation of ultrathin polymeric films near the glass transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3221 (2000).

Dehghani, M., Asghari, M., Mohammadi, A. H. & Mokhtari, M. Molecular simulation and Monte Carlo study of structural-transport-properties of peba-mfi zeolite mixed matrix membranes for CO2, CH4 and N2 separation. Comput. Chem. Eng. 103, 12–22 (2017).

Asghari, M., Mosadegh, M. & Harami, H. R. Supported PEBA-zeolite 13X nano-composite membranes for gas separation: Preparation, characterization and molecular dynamics simulation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 187, 67–78 (2018).

Asghari, M., Sheikh, M. & Dehghani, M. Comparison of ZnO nanofillers of different shapes on physical, thermal and gas transport properties of PEBA membrane: Experimental testing and molecular simulation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93, 2602–2616 (2018).

Golzar, K., Modarress, H. & Amjad-Iranagh, S. Effect of pristine and functionalized single-and multi-walled carbon nanotubes on CO2 separation of mixed matrix membranes based on polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIM-1): A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Mol. Model. 23, 266 (2017).

Golzar, K., Modarress, H. & Amjad-Iranagh, S. Separation of gases by using pristine, composite and nanocomposite polymeric membranes: A molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Membr. Sci. 539, 238–256 (2017).

Rashidi, N. & Nasirian, D. The effect of ZIF-90 particle in Pebax/PSF composite membrane on the transport properties of CO2, CH4 and N2 gases by molecular dynamics simulation method. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 28, 2267 (2019).

Allinger, N. L., Yuh, Y. H. & Lii, J. H. Molecular mechanics. The MM3 force field for hydrocarbons. 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 8551–8566 (1989).

Cornell, W. D. et al. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179–5197 (1995).

Mosadegh, M., Amirkhani, F., Harami, H. R., Asghari, M. & Parnian, M. J. Effect of Nafion and APTEOS functionalization on mixed gas separation of PEBA-FAU membranes: Experimental study and MD and GCMC simulations. Sep. Purif. Technol. 247, 116981 (2020).

Suleman, M. S., Lau, K. & Yeong, Y. Characterization and performance evaluation of PDMS/PSF membrane for CO2/CH4 separation under the effect of swelling. Procedia Eng. 148, 176–183 (2016).

Madaeni, S. S., Badieh, M. M. S. & Vatanpour, V. Effect of coating method on gas separation by PDMS/PES membrane. Polym. Eng. Sci. 53, 1878–1885 (2013).

Mannan, H. A. et al. Recent applications of polymer blends in gas separation membranes. Chem. Eng. Technol. 36, 1838–1846 (2013).

Balta, S. et al. A new outlook on membrane enhancement with nanoparticles: The alternative of ZnO. J. Membr. Sci. 389, 155–161 (2012).

Farias, S. A., Longo, E., Gargano, R. & Martins, J. B. CO2 adsorption on polar surfaces of ZnO. J. Mol. Model. 19, 2069–2078 (2013).

Kokes, R. & Glemza, R. Thermodynamics of adsorption of carbon dioxide on zinc oxide. J. Phys. Chem. 69, 17–21 (1965).

Azizi, N., Mohammadi, T. & Behbahani, R. M. Synthesis of a PEBAX-1074/ZnO nanocomposite membrane with improved CO2 separation performance. J. Energy Chem. 26, 454–465 (2017).

Riasat Harami, H., Asghari, M. & Mohammadi, A. H. Magnetic nanoFe2O3-incorporated PEBA membranes for CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separation: Experimental study and grand canonical Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations. Greenhouse Gases Sci. Technol. 9, 306–330 (2019).

Harami, H. R. et al. Mass transfer through PDMS/zeolite 4A MMMs for hydrogen separation: Molecular dynamics and grand canonical Monte Carlo simulations. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 108, 104259 (2019).

Wang, X.-Y. et al. Molecular simulation and experimental study of substituted polyacetylenes: Fractional free volume, cavity size distributions and diffusion coefficients. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 12666–12672 (2006).

Yampolskii, Y. P. Methods for investigation of the free volume in polymers. Russ. Chem. Rev. 76, 59–78 (2007).

Harami, H. R. & Asghari, M. 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane-aided cross-linked chitosan membranes for gas separation: Grand canonical Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Model. 25, 49 (2019).

Li, H., Freeman, B. D. & Ekiner, O. M. Gas permeation properties of poly (urethane-urea) s containing different polyethers. J. Membr. Sci. 369, 49–58 (2011).

Wolińska-Grabczyk, A. & Jankowski, A. Gas transport properties of segmented polyurethanes varying in the kind of soft segments. Sep. Purif. Technol. 57, 413–417 (2007).

Şen, D., Kalıpçılar, H. & Yilmaz, L. Development of polycarbonate based zeolite 4A filled mixed matrix gas separation membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 303, 194–203 (2007).

Ruiz-Treviño, F. & Paul, D. Modification of polysulfone gas separation membranes by additives. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 66, 1925–1941 (1997).

Şen, D., Kalıpçılar, H. & Yılmaz, L. Gas separation performance of polycarbonate membranes modified with multifunctional low molecular-weight additives. Sep. Sci. Technol. 41, 1813–1828 (2006).

Larocca, N. & Pessan, L. Effect of antiplasticisation on the volumetric, gas sorption and transport properties of polyetherimide. J. Membr. Sci. 218, 69–92 (2003).

Khosravanian, A. et al. Grand canonical Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations of the structural properties, diffusion and adsorption of hydrogen molecules through poly (benzimidazoles)/nanoparticle oxides composites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43, 2803–2816 (2018).

Fox, T. G. Influence of diluent and of copolymer composition on the glass temperature of a polymer system. Bull. Am. Phys. Soc. 1, 123 (1956).

Golzar, K., Amjad-Iranagh, S., Amani, M. & Modarress, H. Molecular simulation study of penetrant gas transport properties into the pure and nanosized silica particles filled polysulfone membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 451, 117–134 (2014).

Wang, X.-Y., in’t Veld, P. J., Lu, Y., Freeman, B. D. & Sanchez, I. C. A molecular simulation study of cavity size distributions and diffusion in para and meta isomers. Polymer 46, 9155–9161 (2005).

Földes, E. & Turcsányi, B. Transport of small molecules in polyolefins. I. Diffusion of irganox 1010 in polyethylene. J. Appl. Polymer Sci. 46, 507–515 (1992).

Lin, H. & Freeman, B. D. Gas solubility, diffusivity and permeability in poly (ethylene oxide). J. Membr. Sci. 239, 105–117 (2004).

Mozaffari, F., Eslami, H. & Moghadasi, J. Molecular dynamics simulation of diffusion and permeation of gases in polystyrene. Polymer 51, 300–307 (2010).

Freeman, B. & Pinnau, I. Polymer membranes for gas and vapor separation. 733 (ACS Publications, 1999).

Smit, B. Grand canonical Monte Carlo simulations of chain molecules: adsorption isotherms of alkanes in zeolites. Mol. Phys. 85, 153–172 (1995).

Tocci, E. et al. Transport properties of a co-poly (amide-12-b-ethylene oxide) membrane: A comparative study between experimental and molecular modelling results. J. Membr. Sci. 323, 316–327 (2008).

Rahman, M. M. et al. PEBAX® with PEG functionalized POSS as nanocomposite membranes for CO 2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 437, 286–297 (2013).

Suleman, M. S., Lau, K. & Yeong, Y. Enhanced gas separation performance of PSF membrane after modification to PSF/PDMS composite membrane in CO2/CH4 separation. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 135, 45650 (2018).

Khalilinejad, I., Sanaeepur, H. & Kargari, A. Preparation of poly (ether-6-block amide)/PVC thin film composite membrane for CO2 separation: Effect of top layer thickness and operating parameters. J. Membr. Sci. Res. 1, 124–129 (2015).

Qin, J.-J. & Chung, T.-S. Development of high-performance polysulfone/poly (4-vinylpyridine) composite hollow fibers for CO2/CH4 separation. Desalination 192, 112–116 (2006).

Basu, S., Cano-Odena, A. & Vankelecom, I. F. MOF-containing mixed-matrix membranes for CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 binary gas mixture separations. Sep. Purif. Technol. 81, 31–40 (2011).

Dai, Y., Johnson, J., Karvan, O., Sholl, D. S. & Koros, W. Ultem®/ZIF-8 mixed matrix hollow fiber membranes for CO2/N2 separations. J. Membr. Sci. 401, 76–82 (2012).

Hu, J. et al. Mixed-matrix membrane hollow fibers of Cu3 (BTC) 2 MOF and polyimide for gas separation and adsorption. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 49, 12605–12612 (2010).

Husain, S. & Koros, W. J. Mixed matrix hollow fiber membranes made with modified HSSZ-13 zeolite in polyetherimide polymer matrix for gas separation. J. Membr. Sci. 288, 195–207 (2007).

Li, T., Pan, Y., Peinemann, K.-V. & Lai, Z. Carbon dioxide selective mixed matrix composite membrane containing ZIF-7 nano-fillers. J. Membr. Sci. 425, 235–242 (2013).

Scofield, J. M. et al. Development of novel fluorinated additives for high performance CO2 separation thin-film composite membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 499, 191–200 (2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing—original draft, Resources, Visualization, Data Curation, Investigation, Formal analysis. A.H.S.D.: Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soleimani, R., Saeedi Dehaghani, A.H. A theoretical probe into the separation of CO2/CH4/N2 mixtures with polysulfone/polydimethylsiloxane–nano zinc oxide MMM. Sci Rep 13, 9543 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36051-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36051-1

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.