Abstract

U-series disequilibrium measurements carried out on thermogenic travertine samples from a 12.6 m-long core and a 10 m-thick section from southeastern Morocco yielded finite ages ranging from 500 ka to the present-day, as well as two clusters determined to be older than 500 ka. The calculation of initial 234U/238U activity ratios in all samples younger than 500 ka shows high, reasonably constant values, with an average of 5.172 ± 0.520 (one standard deviation). Assuming that this value prevailed for periods older than 500 ka, we derived ages of up to approximately 1.2 Ma using the initial 234U excess decay. Our results indicate that the two older clusters have ages of 776 ± 14 ka for samples from between 8 and 10.1 m and 1173 ± 22 ka for deeper samples respectively. The palaeomagnetic record of the core shows normal polarity inclinations from the surface to around 9 m followed by reverse polarity inclination and antipodal declinations. The inversion is attributed to the Brunhes-Matuyama transition. 234U excess ages for the interval corresponding to the part of the core where the polarity inversion occurred are in the range of 735 ± 51 to 794 ± 54 ka, with an arithmetic mean value of 776 ± 14 ka for the B-M transition. This age is in good agreement with that determined previously using other dating methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The U-series method is widely used to date biogenic CaCO3 (corals, mollusk shells), as well inorganic CaCO3 precipitates (speleothems, travertine)1,2 and references in3,4. U-series ages are derived from the activity ratios of 230Th/234U or 230Th/238U and 234U/238U5,6,7. Most terrestrial waters are enriched in 234U8 (i.e., are characterized by an 234U excess), and if the initial value of this excess is known, alternative ages can be calculated from the measured 234U/238U versus the initial 234U/238U ratio (234U/238U initial)9.

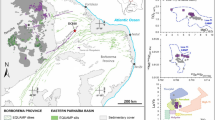

Travertine deposits result from carbon dioxide-rich waters dissolving carbonate rocks at depth and then depositing calcium carbonate when pressure and CO2 decrease at the surface10. Travertine deposits are considered to be remnants of humid episodes, related to a positive hydrological budget11, and dating these deposits is therefore of great interest for climatic reconstruction. In the present study, the two U-series disequilibrium methods were combined to date hydrothermal thermogenic travertine deposits in southeastern Morocco, close to the city of Erfoud (Fig. 1a). The first method uses 230Th-234U-238U from samples younger than 500 ka and the second is based on the decay of initial 234U excess in samples aged between 500 and 1200 ka.

(a) The sampling location, Irdi, close to the city of Erfoud in southeastern Morocco (photo generated from https://earth.google.com/web/, version 9.2.80.4). (b,d,e) Different types of travertine samples encountered, showing anarchic growth with pure calcite layers alternating with clay levels, especially in the upper part. (c) Some sections of the 12.6 m-long extracted core, with the substratum at the base (left to right: top to bottom of the core; base at far right in the image).

In addition, using this combination of the these two approaches, the present study extends the dating limit of U-series to approximately 1.2 Ma which gives us the ability to add new time constraints on the Brunhes-Matuyama magnetic reversal, which are independent of the K-Ar and 40Ar/39Ar radiometric dating methods or orbital tuning techniques that are usually used to date this transition.

Materials and Methods

Sampling

Samples were collected from a single section, approximately 10 meters long and 50 m wide, that was exposed as result of road construction, as well as from a 12.6 m-long core from Irdi, close to the city of Erfoud (Fig. 1b,c).

A few samples from the 10 × 50 m section were already dated12 via U-series using alpha spectrometry, and these results are reported along with the results obtained through the present study. The section is comprised of white, extremely clean CaCO3 layers alternating with brown or yellow layers with occasionally black beds. It is worth noting that the stratigraphic order was partially perturbed by recent pulses of hydrothermal activity that cut older travertine layers (Fig. 1d,e). As a result, stratigraphic layers cannot be directly correlated, and only chronological age dating can be used for this. A total of 12 samples from this section and nearby outcrops were analyzed by U-series. The core was also sampled for the carbonate facies. In the core, very clean CaCO3 layers were again found to alternate with darker brown layers. Sampling was determined by the lithology, and we focused on the clean CaCO3 layers, avoiding the discolored layers due to potential problems with detrital 230Th. A total of 26 samples were collected from the core (Table 1). For all U-series samples collected from the outcrop, zones showing stratigraphic perturbations were avoided and only layers following the laws of superposition were chosen for dating. In a similar way, sub-sampling from the core for U-series as well paleomagnetic plugs were all from visually undisturbed depths. For this reason the paleomagnetic and U-series samples have not been collected at regular intervals and any potentially perturbated areas have been avoided.

Analytical methods

U-series

Pieces of travertine ranging between 0.5 to 1 g were cut using a DremelTM diamond saw and washed with distilled water. The travertine samples were covered by desionized water and dissolved using clean distilled concentrated nitric acid in a Teflon beaker, into which weighed amounts of mixed 233U-236U-229Th spike was added and evaporated to dry at low temperature ~60 °C. Chemical extractions and purifications performed similarly to in13; briefly, U and Th were co-precipitated with Fe(OH)3. The precipitate was washed twice with water, and then dissolved in 6 N HCl. The U-Th separation was performed on a 2 ml volume of AG1X8 anionic resin. The Th fraction was recovered by elution with 6 N HCl and the U and Fe fractions by H2O. The U fraction was purified in a 0.2 ml volume of U-Teva (Elchrom industryTM) resin. The Fe was eluted with 3 N HNO3, and the U fraction with 0.02 N HNO3. Thorium purification was carried out on a 2 ml AG1X8 resin in 7 N HNO3 and eluted with 6 N HCl. After drying, a final purification step was performed on a 0.2 ml AG1X8 resin in 7 N HNO3, and Th was eluted with 6 N HCl. U-Th measurements were performed using a VG sector thermal ionisation mass spectrometer (TIMS) fitted with an electrostatic filter and a Daly ion counter. The U and Th fractions were deposited on a single zone-refined rhenium filament between two layers of colloidal graphite. U and Th isotopes were measured in peak jumping mode on the Daly ion counter.

A few samples from depths of greater than 8.1 m were analyzed by multi-collector inductively mass spectrometry, a Nu II instrument TM MC-ICP-MS, in order to achieve higher precision. The mass spectrometry analyses were performed at Geotop, Montreal14. For samples measured by alpha spectrometry at the IPH laboratory of Paris, the spike was 232U-228Th and the final U and Th fractions were plated on discs covered with an aluminum film and counted in EGG Ortec alpha detectors. The overall analytical reproducibility was estimated through replicate measurements of a coral from Mayo Island (Cabo Verde) that dates from last interglacial age (see supplementary materials). Precision is typically better than 1% for TIMS and MC-ICP-MS, and 3–5% at 2 σ levels for alpha spectrometry.

Paleomagnetism

Paleomagnetism applied to Quaternary speleothems and travertine formations has led to increased interest in relation to their potential as climate archives15. When such archives contain small amounts of ferromagnetic minerals, they can provide high-resolution records of the geomagnetic field16,17. Fifty discrete samples were taken from the core, from 1 to 12.6 meters depth. Samples were taken every 15 to 50 centimeters, perpendicular to the core length, using a 2.6 cm-diameter drill. The magnetization of these samples was measured using a horizontal 2 G cryogenic magnetometer at ENS Paris. Natural remanent magnetization (NRM) intensities vary from a few 10−6 Am−1 to 10−3 Am−1. Samples were demagnetized using alternating field (AF) up to 90 mT, and a characteristic direction was successfully determined for the majority of the samples using principal component analysis18. Thermal demagnetization has been tested for six pilot samples. Secondary magnetization is erased above 200 °C or a few mT. Thermal and AF demagnetization give reproducible results.

In addition 49 small plugs of 1.5 cm diameter (vol = 2.5 cm3) were sampled between 8.69 and 9.84 m with a sampling step of 2 to 2.5 cm in order to refine the critical interval revealed by the analysis of the 2.6 cm cores. These samples underwent stepwise alternating field (AF) demagnetization in 6–8 steps between the natural remanent magnetization (NRM) and 70 mT using a Shonstedt demagnetizer at IPGP, steps to higher values were not performed due to suspicion for lack of stability of the instrument. Magnetization was measured using a 2 G cryogenic magnetometer at IPGP. NRMs range between 5 10−5 to 1 10−2 Am−1. Orthogonal vector plots using Paleomac software19 were used for principal component analysis.

IRM acquisition curves were performed on the 2.5 and 1.5 cm plugs up to 2.5 T for 20 representative samples. A thermomagnetic experiment was attempted using one of the most magnetized samples (at 8.97 m). The sample was crushed and dissolved in a 1 l aqueous solution of acetic acid (2% vol) for 2 h, the recovered solid product was rinsed, dried and subjected to treatment using a KLY-3 equipped with a CS-3 allowing the measurement of the temperature variations of the low field susceptibility. Even with such preparation the signal over noise ratio was poor. The low concentration of remanence bearing minerals in our samples did not allow more in depth rock magnetic investigations.

Results and Discussion

Stable isotopes of oxygen (δ18O) and carbon (δ13C) are often use to investigate the origin and in some case to estimate the temperatures of the parental fluids20,21 in all our samples δ13C (V-PDB) show a positive values spanning from 2.7 to 6.4 while δ18O (V-PDB) varies from −10.2 to −7.3 (V-PDB). According to the isotopic compositions (particularly δ13C) our samples fall clearly into the typical class of thermogenic travertine20,21 (see supplementary materials).

The U concentration of our samples varies between 0.7 and 7.8 ppm; this is relatively high compared with those reported for other inorganic CaCO3 precipitates (speleothems, flowstones)22,23 or biogenic CaCO3 (mollusks shells, calcite corals)2,24,25. The 232Th concentration of the samples is low, varying between 0.2 and 6 ppb. As a result, detrital contamination is assumed to be negligible and no correction was applied for any of the samples. The 234U/238U activity ratio of the calcite varies from approximately 5 in samples younger than 20 ka to 1.13 in samples from the deepest part of the core. The 230Th/234U activity ratios were below secular equilibrium in all samples collected from the road section, and in samples from the upper 5.6 m of core, thus allowing 230Th/234U/238U ages for these samples to be calculated. The 230Th/234U/238U ages vary between 10 to 500 ka, depending on their stratigraphic position. Conversely, core samples from below 5.6 m have 230Th/234U values close to and/or reaching secular equilibrium, within analytical error. In a few cases for the lower part of core, particularly for samples characterized by high analytical precision (mostly those analyzed by MC-ICP-MS), we were able to calculate the finite ages associated with the large negative errors that result from subtracting the 230Th/234U analytical errors and adding the 234U/238U activity ratio analytical error due to the exponential nature of the radioactive decay phenomena. On the other hand, it was not possible to calculate the positive errors on the ages, because when the errors are summed, the samples reach secular equilibrium and the ages tend approach infinity (Table 1).

Plotting the measured 230Th/238U and 234U/238U on the classical isotope evolution diagram (Fig. 2), we observe that most of samples for which finite ages were determined, from the section and the upper 5.6 m of the core, are situated on or close to the curve corresponding to the evolution of an initial 234U/238U ratio of approximately 5. The arithmetic mean of the initial 234U/238U ratio calculated for all samples yielding finite 230Th ages (n = 17) is 5.172 ± 0.520 (one standard deviation, Fig. 3). The high value of the initial 234U/238U0 corresponds to the uranium isotopic composition of the water from which the calcite was precipitated. Such high disequilibrium in water is often observed as a result of recoil effects26,27 and /or preferential leaching of 234U28. It is worth noting that the relative stability and high initial 234U/238U has previously been observed in hydrothermal carbonates. For example Gratier et al.29 observed a relatively constant initial 234U/238U (4.19 to 4.26) over ca. 1000 y in travertines from the Colorado plateau (Utah). They suggested that the constant initial 234U/238U reflects a constant fluid composition. Rhis et al.30 also found a remarkably constant initial 234U/238U over a relatively long period ~250 ka in hydrothermal carbonates from the Massif Central (France). To explain this constant initial 234U/238U Rhis et al.30 suggested the presence of deep geothermal reservoirs rocks rich in uranium that reach a steady state condition (or near steady state) with respect to water-rock interactions. In these geothermal reservoirs U is accumulated in reduced and poorly crystallized hydrothermally altered minerals that can act as a source for U to thermal water by preferential leaching and/or α recoil release. Finally another example of constant initial 234U/238U during the last 500 ka was also observed for the Devils Hole calcite vein, allowing Ludwig et al.9 to test the agreement between 230Th/234U/238U and 234U excess ages enabling him to suggest that the system had remained closed. However, recently, the closed system assumption at Devils Hole has been challenged by Moseley et al.31 because the results disagree with orbital forcing glacial-interglacial cycles. A similar mechanism can be evoked as a potential explanation to our constant initial 234U/238U. (i) The infiltration fluids reach a steady state with respect to water-rock interactions. (ii) The fluids use the same more or less pathways during infiltration (iii) The fluids show very limited variations in their physicochemical properties.

Regardless the mechanisms responsible for the nearly constant initial 234U/238U, samples located deeper in the core show two clusters: the first located between 8 and 10.1 m and the second from 10.6 to 12.6 m (Fig. 2b). For these two depth intervals, 230Th/234U/238U age calculations for majority of samples indicate infinite ages or a high negative error, as described above, and so we attempted to calculate the 234U excess ages for these two levels.

Normally, the 230Th/234U values preclude the possibility of obtaining ages older than 500 ka with reasonable errors. However, the high 234U/238U value of the initial system, 5.172 ± 0.520 (Fig. 3), makes it possible to go further back in time. For instance, if the starting point is an initial 234U/238U value of 5.172 ± 0.520, and initial 230Th = 0, after approximately 800 ka (as is the case for samples located between 8–10.1 m deep in the core), the measured 230Th/234U would be 1.132 ± 0.012 (uncertainty from the initial 234U/238U) and the 234U/238U value would be approximately 1.435 ± 0.054. Using these ratios to calculate 230Th age yields a meaningless age (with uncertainties greater than the age itself). As seen in Fig. 4 after 500 ky the 230Th/234U reached practically asymptotic part of the evolution curve, thus even small analytical errors will results in huge uncertainties on age calculations. On the other hand the 234U/238U activity ratios still indicate value with an easily measurable disequilibrium value, thus allowing an age to be calculated based on the decay of 234U excess (Fig. 4).

: Evolution of the activity ratios, 234U/238U and 230Th/234U, with an initial 234U/238U0 of 5.172 ± 0.520 and 230Th = 0 in closed radioactive system. Clearly samples older than 500 ky reached the asymptotic part of the 230Th/234U evolution curve while 234U/238U still indicate an easily measurable disequilibrium.

Assuming that samples from deeper than 5.6 m in the core were precipitated from an aqueous phase similar to the upper part of the core, with an initial 234U/238U of 5.172 ± 0.520, 234U excess ages can be calculated for the lower part of the core using the following equation32:

where (234U/238U)0 is the calculated initial 234U/238U activity ratio; 234U/238Ut is the measured 234U/238U activity ratio; λ234 is the U decay constant, 234U; and t is the 234U excess age.

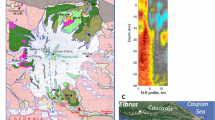

Using the above equation, we calculated 234U excess ages for all samples from deeper than 5.6 m in the core (Table 1). The maximum errors associated with these age calculations were determined by combining the highest initial 234U/238U value + 1 standard deviation with the lowest measured 234U/238U value – 2 σ, and vice versa. The 234U excess ages in the present case allow the calculation of older ages than would be possible through the usual U-series dating (~500 ka). Figure 4 shows the evolution of the activity ratios, 234U/238U and 230Th/234U, with an initial 234U/238U value of 5.172 ± 0.520 in a closed radioactive system. As seen in Fig. 5, when the calculated 230Th/234U/238U and 234U excess ages are plotted as a function of depth in the core, samples located between 8 to 10.1 m and 10.6 to 12.6 m depth yield ages clearly clustered into two periods of time; the first, 776 ± 14 ka, corresponds to an at least 2.1 m-thick travertine unit, and the second, 1173 ± 22 ka, corresponds to an approximately 2 m-thick unit. The results also show that travertine accretions seem to correspond to pulses of hydrothermal activity, which allows the precipitation and accumulation of thick CaCO3 layers over relatively short time intervals.

Ages and paleomagnetic results vs depth, the vertical grey line marks the Brunhes-Matuyama transition determined after the paleomagnetic results (a) Isotopic ratios and ages determined using the standard 230Th/U approach and the new 234U/U0 ages, horizontal grey line is mean age for B-M obtained by Channel et al.36 (773 ka). (b) Paleomagnetic declinations, red circles are data from the 2.5 cm plugs, black diamonds from the 1.5 cm plugs, the core is reoriented so that the mean declination is along the N-S direction, dashed lines are the 0 and 180° expected dipole values. (c) same than (b) for paleomagnetic inclinations, dashed lines are the + 51° and −51° expected dipole value.

Fifty eight samples (28 1.5 cm plugs and 30 2.5 cm plugs) provided demagnetization paths with convergence towards the origin allowing to determine characteristic remanent magnetization (ChRM) directions (Fig. S1-a). The other samples have erratic behavior mostly associated to poor signal/noise ratio (with bulk magnetization sometimes on the order of 10−10 Am2) or gyromagnetic remanence. The demagnetization loss at 70 mT is between 95 to only 60% in few cases. IRM experiments up to 2.5 Tesla confirm that the remanent magnetization in all samples is dominated by a low coercivity phase, in addition to a high coercivity phase (characterized by magnetization acquired above 300 mT) in variable proportion (Fig. S1-b). The low coercivity phase is interpreted as being magnetite, the high coercivity phase hematite and/or goethite in accordance with previous results from travertine (e.g. Piper et al.33; Lebatard et al.34). The thermomagnetic curve from the sample at 8.97 m (Fig. S1-c) depicts a mere hump until 400 °C which is compatible with magnetite but a transformation starting at 450 °C and attributed to the decomposition of siderite into magnetite (Pan et al.35), did not allow to characterized further the magnetic mineralogy.

In spite of the difficulty in characterizing further the magnetic mineralogy, the low coercivity phase is the dominant remanence carrier in all samples and straight line fits of the ChRM to the origin indicates that, when present, high coercivity phases do not carry a different direction of magnetization, giving confidence in the results. Resultant paleomagnetic inclinations and declinations after demagnetization are shown in Fig. 5. Throughout the section the inclination changes from reverse direction with a mean of −42° to normal direction with a mean of 43°. The inclination record is shallower but overall consistent with the current expected geocentric axial dipole field inclination for the location from which the core was sampled (51°). Declination is rotating by 180° at a level coincident with the change in the sign of inclination. The dense sampling between 8.49 and 9.86 m allows to precisely localized the change in direction at around 9.04 m where low NRM did not allow to isolate a ChRM. One of the small plug at depth of 9.55 m is giving a normal polarity direction, this may be a true geomagnetic event but we cannot ruled out the occurrence of a restrained remagnetization event. The magnetic polarity sequence data allows the inversion at ~9.04 m to be attributed to the Brunhes-Matuyama (B-M) transition. The latest mean age suggested for this reversal is 773.1 ka36. The average weighted age obtained here through the 234U excess dating approach (776 ± 14) is in excellent agreement with previous results using other methods1.

Conclusions

The combination of 230Th/U dating with the 234U excess approach applied to a travertine sequence in Morocco allows U-series dating to be extended to approximately 1.2 million years, if the assumption of a constant initial 234U/238U is valid. In the present study, a time constraint on the Brunhes-Matuyama magnetic polarity inversion is obtained through this approach using U-Series (776 ± 14 ka) and is in good agreement with the age of the inversion previously obtained using other dating methods, such as K-Ar and 40Ar/39Ar argon family methods37,38. According to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the B-M reversal has been radiometrically dated using the U-series approach applied to continental calcium carbonates.

References

Kaufman, A., Broecker, W. S., Ku, T.-L. & Thurber, D. L. The status of U-series methods of mollusk dating. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 35, 11155–1183 (1971).

Kaufman, A., Ghaleb, B., Wehmiller, J. F. & Hillaire-Marcel, C. Uranium concentration and isotope ratio profiles within Mercenaria shells: Geochemical implications. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 60, 3735–3746 (1996).

Ivanovich, M. & Harmon, R.S. Uranium-series Disequilibrium: Applications to Earth, Marine and Environmental Sciences, 2nd edition pp.571 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992).

Bourdon, B., Turner, S., H, G.M., Lundstrom C. C. Eds,. Uranium-Series Geochemistry, Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 52, The Mineralogical Society of America, Washington (2003).

Richards, D. A. & Dorale, J. A. Reviews in Mineralogy & Geochemistry 52, 407–460 (2003).

Genty, D. et al. Precise dating of Dansgaard–Oeschger climate oscillations in western Europe from stalagmite data. Nature. 421, 833–837 (2003).

Shen, C. C. et al. High-precision and high-resolution carbonate 230Th dating by MC-ICP-MS with SEM protocols. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 99, 71–86 (2012).

Cherdyntsev, V. V. Uranium-234. Israel program for scientific translations. Jerusalem (1971).

Ludwig, K. R. et al. Mass-spectrometric 230Th-234U-238U dating of the Devils Hole calcite vein. Science. 258, 284–287 (1992).

Breckenridge, R. M. & Hinckley, B. S. Thermal springs of Wyoming. Geological Survey of Wyoming, Bulletin. 60, 1–104 (1978).

Weisrock, A. et al. Travertins de la bordure nord du Sahara marocain: dispositifs morphologiques, datations U/Th et indications paléoclimatiques. Géomorphologie, relief, processus, environnement. 3, 153–167 (2008).

Boudad, L. et al. Datation par la méthode U/Th d’un travertin quaternaire du Sud-Est marocain: implications paléoclimatiques pendant le Pléistocène moyen et supérieur. C.R. Géoscience. 335, 469–478 (2003).

Pons-Branchu, E., Hillaire-Marcel, C., Deschamps, P., Ghaleb, B. & Sinclair, D. J. Early diagenesis impact on precise U-series dating of deep-sea corals: example of a 100–200-years old Lophelia pertusa sample from the northeast Atlantic. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 69, 4865–4879 (2005).

Ponte, J. M., Font, E., Veiga-Pires, C., Hillaire-Marcel, C. & Ghaleb, B. The effect of speleothem surface slope on the remanent magnetic inclination. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 122, 4143–4156 (2017).

Lascu, I. & Feinberg, J. M. Speleothem magnetism. Quat. Sci. Rev. 30, 3306–3320 (2011).

Latham, A. G. & Ford, D. C. The palaeomagnetism and rock magnetism of cave and karat deposits. in Applications of Palaeomagnetism to Sedimentary Geology, SEPM Special Publication. 49, 149–155 (1993).

Stock, G. M., Granger, D. E., Sasowsky, I. D., Anderson, R. S. & Finkel, R. C. Comparison of U-Th, paleomagnetism, and cosmogenic burial methods for dating caves: implications for landscape evolution studies. Earth and Planet. Sci. Lett. 236, 388–403 (2005).

Kirschvink, J. L. The least-squares line and plane and the analysis of palaeomagnetic data. Geophys. J. R. astr. Soc. 62, 699–718 (1980).

Cogné, J. P. PleoMac: A MacintoshTM application for treating paleomagnetic data and making plate reconstructions. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 4, 1–8 (2003).

Billi, A. et al. First records of syn-diagenitic non –tectonic folding in quaternary thermogene travertines caused bu hydrothermal incremental veining. Tectonophiscs. 700–701, 60–79 (2017).

Pentecost, A. Travertine, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg. 445 pp (2005).

Bard, E., Antonioli, F. & Silenzi, S. Sea-level during the penultimate interglacial period based on a submerged stalagmite from Argentarola Cave (Italy). Earth Planet. Sci Lett. 196, 135–146 (2002).

Falguères, C. et al. New U-series dates at the Caune de l’Arago, France. J. Archaeological. Sci. 31, 941–952 (2004).

Bard, E., Hamelin, B. & Fairbanks, R. G. U/Th ages obtained by mass spectrometry in corals from Barbados sea level during the past 130,000 years. Nature. 346, 456–458 (1990).

Ayling, B. F. et al. Uranium uptake history, open-system behaviour and uranium-series ages of fossil Tridacna gigas from Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 213, 475–501 (2017).

Kigoshi, K. Alpha-recoil thorium-234: Dissolution into water and the uranium-234/uranium-238 disequilibrium in nature. Science 173, 47–48 (1971).

Osmond, J. K. & Cowart, J. B. Ground water. In: Uranium-series Disequilibrium: Applications to Earth, Marine and Environmental Sciences 2nd edition. Ivanovich, M. & Harmon, R.S. (eds) 290–333 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992).

Fleischer, R. L. & Raabe, R. O. Recoiling alpha-emitting nuclei: mechanisms for uranium-series disequilibrium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 42, 973–978 (1978).

Gratier, J.-P. et al. How travertine veins grow from top to bottom and lift rocks above them: Th effects of crystalizaion force. Geology. 40, 1015–1018 (2012).

Rhis, S., Condomines, M. & Poidevin, J.-L. Long-term behaviour of continental hydrothermal system: U-series study of hydrothermal carbonates from the French Massif Central (Allier Valley). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 64, 3189–3199 (2000).

Moseley, G. E. et al. Reconciliation of Devils Hole climate record with orbital forcing. Science, 351, 165–168 (2016).

Ivanovich, M., Latham, A. G. & Ku, T. L. In: Uranium-series Disequilibrium: Applications to Earth, Marine and Environmental Sciences 2nd edition. Ivanovich, M. & Harmon, R. S. (eds) 62–94 (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992).

Piper, J. D., Mesci, L. B., Gürsoy, H. T. O. & Davies, C. J. Palaeomagnetic and rock magnetic properties of travertine: its potential as a recorder of geomagnetic palaeosecular variation, environmental change and earthquake activity in the Sıcak Cermik geothermal field, Turkey. Phys. Earth. Planet. Interiors. 161(1-2), 50–73 (2007).

Lebatard, A. E. et al. Dating the Homo erectus bearing travertine from Kocabaş (Denizli, Turkey) at at least 1.1 Ma. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 390, 8–18 (2014).

Pan, Y., Zhu, R., Banerjee, S. K., Gill, J. & Williams, Q. Rock magnetic properties related to thermal treatment of siderite: behavior and interpretation. J. Geophys. Res: Solid Earth. 105(B1), 783–794 (2000).

Channel, J. E. T., Hodell, D. A., Singer, B. S. & Xuan, C. Reconciling astrochronological and 40Ar/39Ar ages for the Matuyama‐Brunhes boundary and late Matuyama Chron. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 11, 1–21 (2010).

Singer, B. S. et al. Structural and temporal requirements for geomagnetic field reversal deduced from lava flows. Nature. 434, 633–636 (2005).

Quidelleur, X., Carlut, J., Soler, V., Valet, J.-P. & Gillot, P.-Y. The age and duration of the Matuyama-Brunhes transition from new K-Ar data from La Palma (Canary Islands) and revisited 40Ar/39Ar ages. Earth. Planet. Sci. Lett. 208, 149–163 (2003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.G. contributed to ICPMS and TIMS analyses, C.F. contributed to U-series analyses using alpha spectrometry, J.P.P., J.C. contributed to Palaeomagnetic analyses, and G.M., L.R. and L.B. organized the core sampling and other field work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghaleb, B., Falguères, C., Carlut, J. et al. Timing of the Brunhes-Matuyama transition constrained by U-series disequilibrium. Sci Rep 9, 6039 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42567-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42567-2

This article is cited by

-

Exploring possible links between Quaternary aggradation in the Upper Rhine Graben and the glaciation history of northern Switzerland

International Journal of Earth Sciences (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.