Abstract

To meet the challenge of feeding a growing world population with minimal environmental impact, we need comprehensive and quantitative knowledge of ecological factors affecting crop production. Earthworms are among the most important soil dwelling invertebrates. Their activity affects both biotic and abiotic soil properties, in turn affecting plant growth. Yet, studies on the effect of earthworm presence on crop yields have not been quantitatively synthesized. Here we show, using meta-analysis, that on average earthworm presence in agroecosystems leads to a 25% increase in crop yield and a 23% increase in aboveground biomass. The magnitude of these effects depends on presence of crop residue, earthworm density and type and rate of fertilization. The positive effects of earthworms become larger when more residue is returned to the soil, but disappear when soil nitrogen availability is high. This suggests that earthworms stimulate plant growth predominantly through releasing nitrogen locked away in residue and soil organic matter. Our results therefore imply that earthworms are of crucial importance to decrease the yield gap of farmers who can't -or won't- use nitrogen fertilizer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Our global food production system faces the unprecedented challenge of feeding a rapidly increasing world population while simultaneously reducing its environmental footprint1. It is still far from clear whether such a “sustainable intensification”2 can be achieved. In particular, the question of what determines the yield gap between more sustainable forms of agriculture and those of conventional agriculture and how to close that gap, is still widely debated3,4. Earthworms are generally thought to be essential to sustainable agroecosystems. They rank among the most important soil fauna and as ‘ecosystem engineers’ they are instrumental to several ecosystem services the soil provides, such as nutrient cycling, drainage and regulating greenhouse gas emissions5,6. However, it is their supposed ability to stimulate crop growth that might be of foremost relevance to agriculture. This ability was already suggested in an age before artificial fertilizers and mechanization provided a short-cut towards higher crop production7,8.

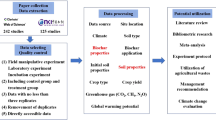

Although positive effects of earthworms on plant growth have been repeatedly described9,10, quantitative proof has remained elusive and mechanisms through which it might be exerted have never been satisfactorily established. Yet, this information is essential to determine whether earthworms can help to fill the yield gap between sustainable and conventional agriculture. Such an effort has previously been hampered by the wide variety of conditions (climate, soil fertility, crop types, earthworm species and farm management) under which the effects of earthworms have been studied, making it difficult to determine the global effect of earthworms response from individual observations. A quantitative synthesis of results across multiple studies can overcome this problem. Here, for the first time, we use meta-analysis to summarize the effect of earthworms on plant production across the globe (see Methods). We collected 462 data points from 58 studies that were published between 1910–2013 (Supplementary Table 1). Studies include the three main global staple crops (maize, rice and wheat), pastures, as well as many other food crops and were conducted on all continents except Antarctica.

We assessed the generality of the effect of earthworm presence on six key plant response variables: (1) crop yield; (2) aboveground biomass; (3) belowground biomass; (4) total biomass; (5) shoot/root ratio (as a proxy for carbon allocation towards harvestable products); and (6) nitrogen (N) concentration in aboveground biomass (as a proxy for crop quality) (Supplementary Tables 2–5). Earthworm presence significantly increased crop yield by +25%, aboveground biomass by +23%, belowground biomass by +20% and total biomass by +21% (Fig. 1). Shoot/root ratio was not significantly different from zero, indicating no proof of altered carbon allocation towards aboveground plant parts11. Nitrogen concentration in aboveground biomass was also unaffected by earthworm presence (Fig. 1), indicating that crop quality was maintained.

Results of a meta-analysis on the effect of earthworm presence on yield, aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, total biomass, shoot/root ratio and N concentration of aboveground biomass.

Effect sizes in all meta-analyses were weighted by the inverse of the pooled variance. The number of observations in each class is shown between parentheses; error bars denote the 95% confidence range.

Because previous studies suggested that the effect of earthworms differs between crop types9, we tested the effect of earthworm presence on aboveground biomass of the major grain crops and ryegrass. Aboveground biomass was significantly increased in all crops (Fig. 2a), averaging +31% across all grain crops and +24% across all pasture grasses (Fig. 2b).

Influence of crop species, crop type and pasture type on the effect of earthworm presence on aboveground biomass, (a–c).

Influence of crop species (a), type of crop/grasses (b) and type of pasture (c) on the effect of earthworm presence. Effect sizes in all meta-analyses were weighted by the inverse of the pooled variance. The number of observations in each class is shown between parentheses; error bars denote the 95% confidence range.

How do earthworms stimulate plant production? Brown et al.12 proposed 5 possible pathways through which earthworm can positively affect plant growth: (i) biocontrol of pests and diseases; (ii) stimulation of microbial plant symbionts; (iii) production of plant-growth regulating substances; (iv) soil structure changes; and (v) increased nutrient availability. The last two mechanisms were the most consistently mentioned in early literature7. More recent studies suggested earthworm-induced regulation of plant defence mechanisms as additional pathways13,14,15.

However, our results suggest that increased N availability is a dominant pathway by which earthworms stimulate plant growth. We tested this by splitting our data according to fertilizer N application rates (Fig. 3a). When application rates exceeded 30 kg N ha−1 yr−1, the earthworm effect decreased from +19% to +9% and was not significantly different from zero anymore, suggesting that earthworms stimulate plant growth by increasing N mineralization. The effect of earthworms on plant growth in studies applying organic (N) fertilizer (+34%) was significantly stronger than in studies applying inorganic fertilizer (+10%) or no fertilizer (+20%), further implicating increased N mineralization as a major pathway (Fig. 4). Our results are consistent with studies showing the potential of earthworms to increase N mineralization from crop residues and soil organic matter, depending on earthworm community and environmental conditions16,17.

Influence of N fertilization rate and crop residue application rate on the effect of earthworm presence on aboveground biomass, (a–b).

Influence of fertilizer N rate (a) and crop residue application rate (b) on the effect of earthworm presence. N fertilization rates include both chemical and organic (manure) fertilizer. Effect sizes in all meta-analyses were weighted by the inverse of the pooled variance. The number of observations in each class is shown between parentheses; error bars denote the 95% confidence range.

If N mineralization is the main pathway, the positive effect of earthworms should be smaller for plants capable of symbiotic N2 fixation. Indeed, for the legume crops in our dataset the earthworm effect ceased to be significant (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, when legumes were present in pastures, the effect of earthworms on pasture productivity disappeared altogether (Fig. 2c).

It is still unclear whether there is any effect of earthworms on nutrients other than N. Although it has been suggested that earthworms increase P availability in their casts18,19, this has not yet been shown to affect plant growth in experimental studies. Legumes, despite their larger need for P than grasses, did not show a positive effect of earthworm presence (Fig. 2b & 2c), which is consistent with a minor role for earthworms on P mobilization.

Both soil organic matter and plant residues can potentially serve as substrates for N mineralization facilitated by earthworms17. To distinguish between the two, we subdivided our dataset in different residue application rate classes (Fig. 3b). Although the earthworm effect on aboveground biomass peaked with +50% at the highest residue application rate, the effect stabilized around +21% at nil and very low residue application rates. This indicates that both soil organic matter and plant residue are sources for earthworm-induced mineralization. Because it has been often suggested that decaying earthworm tissues may be responsible for the observed increased plant N uptake20, we tested for the effect of earthworm survival (Fig. 5a). Earthworm presence did not significantly increase crop yield in experiments with survival rates lower than 50%; therefore the N effect is not an artefact related to decomposing earthworm tissue. This is in line with calculations on the contributions of N released from decaying earthworm tissue in previous experimental studies21, as well as with studies conducted with control treatments receiving dead earthworms22.

Influence of earthworm survival, earthworm density and earthworm ecological category on the effect of earthworm presence on aboveground biomass, (a–c).

Influence of earthworm survival during experiment (a), earthworm density (b) earthworm ecological group (c) on the effect of earthworm presence. The number of observations in each class is shown between parentheses; error bars denote the 95% confidence range.

Although earthworm density had a highly significant effect on aboveground plant biomass, only the highest densities (>400 individuals m−2) differed significantly from lower densities (Fig. 5b). The effect under realistic earthworm densities varied between +10 and +21%. The positive effect was present for all three ecological categories of earthworms that are traditionally distinguished (Fig. 5c).

In experiments where soil was disturbed (that is, homogenized and repacked) prior to the start of the experiment, the earthworm effect on aboveground biomass was almost twice as high as in undisturbed soils (Fig. 4). This result may reflect a beneficial effect of earthworms on restoring the demolished soil structure. As soil structure will be restored after some time, a positive effect of earthworms on plant growth through their effect on soil structure is likely to be a transient effect after soil tillage operations (Fig. 4). Although some studies reported an additional effect of earthworms on plant growth through improving soil structure in undisturbed soil22,23, it generally was difficult to distinguish this effect from increased nutrient availability21. The fact that all three ecological earthworm categories (anecic, epigeic and endogeic), each with distinct burrowing and casting behaviour23,24, had a positive effect on plant growth also argues against soil structure improvement as a major pathway and in favour of enhanced nutrient mineralisation.

Significant positive earthworm effects occur across a range of climate regions, soil textures, soil organic matter contents and soil C/N ratios (Fig. 4). No significant differences were detected between categories of soil organic matter content, possibly because soil organic matter quality was not taken into account. In higher pH soils, the earthworm effect is significantly smaller than in lower pH soils. This may be a confounding effect, since the high pH soils were often linked to systems with low or nil application of residues or organic manure. Earthworm effects were strongest in soils with clay texture and not significant in sandy soils (Fig. 4). This is in marked contrast with an earlier review9 where largest beneficial earthworm effects in tropical regions were achieved on soils with sandy texture.

Which cropping systems would benefit most from earthworms? Because improving N supply in N-limited systems is the main pathway through which earthworms increase plant growth, earthworms are likely to be most beneficial in infertile soils. However, this raises a paradox, because earthworms thrive best in fertile soils with high soil organic matter levels. The paradox disappears in the case of relatively poor soils that depend on crop residue application to maintain soil fertility levels. In those soils, crop residues can serve as food for earthworms and earthworms can increase crop production through increasing N mineralization. This combination of poor soils and reliance on crop residue is particularly found in low-input farming systems in the tropics and to a lesser extent in organic farming systems in the developed world25.

Yet, these systems vary dramatically in terms of habitat quality for earthworms26. In low-input systems in the tropics, low residue quality and residue supply are most likely to be the constraining factor for reaching the full potential of earthworm activity27. Research in these systems should therefore be aimed at judicious use of the limited residue resources available28. Organic farming systems, on the other hand, typically have large application rates of organic manure or high-quality crop residues, providing excellent conditions for earthworm activity29. In those systems, earthworm activity might be crucial in closing the yield gap with conventional agriculture4. Future research in these systems should therefore focus on management strategies to increase earthworm populations. More generally speaking, management practices aimed at sustainable intensification of agriculture should take into account their effect on the earthworm population, because their presence stimulates crop production and will help to bridge the yield gap with conventional agriculture.

Methods

Data compilation

A literature search of peer-reviewed publications published before June 2013 reporting results on the influence of earthworms on plant growth was performed using the ISI-Web of Science research database. We investigated the effect of earthworms on six main response variables concerning plant growth: crop yield, aboveground biomass, belowground biomass, total biomass, shoot/root ratio and N concentration of the aboveground biomass. We used the following search term:

earthworm$ AND (plant biomass OR plant yield OR plant production OR plant growth) AND (crop$ OR grassland$)

We selected the timespan ‘all years’. When we found references in these papers to peer-reviewed publications that were too old to be included in the ISI database, we included them as well when they fitted our selection criteria. We included primary studies in agroecosystems in either temperate/continental or tropical/subtropical climate zones. For annual plants we included studies that reported plant harvest data after a clearly defined experimental period; in the case of multiple harvests over a longer time span of one or more years, we estimated the experimental period for each harvest separately. For perennial plants we included studies that reported harvest data after an explicitly reported experimental period; in the case of an experimental period of multiple years, we expressed harvest data as annual yield.

After carefully checking all of the query results, a total of 58 papers published between 1910 and 2013 fitted our selection criteria for the meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The resulting database covered 130 side by side comparisons of soils with and without earthworms (observations) from 16 papers for crop yield, 378 comparisons from 52 papers for aboveground biomass, 201 comparisons from 35 papers for belowground biomass, 169 comparisons from 27 papers for total biomass, 173 comparisons from 29 papers for shoot/root ratio and 71 comparisons from 12 papers for the N concentration of the aboveground biomass.

For each observation within every study we collected the means of the control treatment (that is, without earthworm presence) and the experimental treatment (that is, with earthworm presence), as well as their standard deviation (SD) and replicate numbers (n). Field studies that had earthworms excluded from their control treatment (for instance, by electro-shocking) were only included when explicitly reported earthworm numbers from these control treatments did not exceed 10% of the earthworm densities in experimental treatments. For studies that did not report SD or SE (standard error; SD = SE × √n) we calculated the average coefficient of variation (CV) for control treatments and experimental treatments and then approximated the missing SD by multiplying the reported mean by the average CV30,31. When data in the original publication were presented graphically, we estimated values from manually digitized figures. Unidentified error bars were, again conservatively, assumed to denote SE rather than SD. In a few cases, we contacted the authors to obtain unpublished SDs (see Acknowledgements).

For the earthworm effect on plant growth, we considered three groups of controlling factors: plant factors, earthworm factors and experimental factors. Table 1 lists the three groups of controlling factors, as well as the subgroups we identified for our analysis that were based on these factors. Factors such as land management strategy, soil moisture content or phosphorus uptake by the plants were also considered, but the range of these parameters published across studies was too narrow to be included in our meta-analysis. For the plant factors we distinguished between most commonly studied crops (that is, ryegrass, barley, maize, wheat, rice), as well as groups of crops (that is, grasses, grain crops, legumes). In order to discern the effect of symbiotic N fixation, pastures were divided into pastures with or without legumes. For the earthworm factors we distinguished between the three earthworm ecological categories (that is, anecic, epigeic and endogeic) that are typically distinguished32 and a fourth subgroup encompassing studies on mixtures of these categories.

Earthworm densities were divided into four subgroups, representing low, intermediate, high and very high densities. These were based on the range of densities that can be found in agroecosystems throughout the world, including arable fields and pastures in tropical and subtropical33 and temperate regions34, as well as artificial densities generally only employed in experiments.

We also categorized studies according to earthworm survival rate, distinguishing between <50%, 50–90% and >90% survival. For experimental factors we distinguished between temperate/continental and tropical/subtropical climates. Soil texture of the bulk soil used in the included studies was categorized in three subgroups (sandy, loamy, clayey) according to textural classes as defined by the USDA35. We divided studies into three subgroups based on soil organic carbon content (<15 g C kg−1, 15–30 g C kg−1, >30 g C kg−1). Studies were split into two subgroups according to critical soil C/N ratios within the context of N mineralization and immobilization, as described by Hodge et al.36 (<12.5 and ≥12.5). Studies were categorized in three subgroups of soil pH (<5.6, 5.6–7.0, >7.0) based on earlier work on the effect of earthworms on plant growth9. Soil pre-treatment was taken into account by dividing the studies in two subgroups: disturbed (re-packed soil) and undisturbed (intact soil columns or field plots). Within undisturbed soil we further distinguished between experiments where treatments were installed by applying earthworms to earthworm treatments (indicating an absence of a significant native earthworm population) and those where treatments were installed by reducing earthworm numbers in control treatments (indicating a significant earthworm population that might have affected soil properties prior to the experiment). We distinguished between four types of N fertilizer application (inorganic, organic, both and none) and two fertilizer application rates (≤30 kg N ha−1 yr−1 and >30 kg N ha−1 yr−1), the cut-off value being determined by maximum atmospheric N depositions in the United States and most of the European Union, following Van Groenigen et al.37. Finally, we divided studies into four subgroups of residue application rates (0 kg C ha−1 yr−1, 0–2999 kg C ha−1 yr−1, 3000–5999 kg C ha−1 yr−1, ≥6000 kg C ha−1 yr−1). These represent the lower and upper spectrum of residue application rates in agroecosystems, ranging from systems where most of the residues are removed (e.g. for biofuel production or construction), via relatively low residue application rates typical of low input systems in developing countries and high residue application rates typical for high input systems in the developed world, to crops producing large amounts of residues (for instance, sugarcane)38.

Most studies comprised several treatments with and without the presence of earthworms, resulting in more than one observation per study. Not all studies provided information on each controlling factor and therefore the number of observations per controlling factor was not always identical to the total number of observations. Results from subgroups of the controlling factors were considered suitable for meta-analysis when a minimum of 10 observations out of at least two independent studies were available.

Meta-analysis

The magnitude of the earthworm-induced effect on the six main response variables in each study was calculated as the natural logarithm of the response ratio (R)39:

where E and C are the means of experimental and control groups, respectively. Response ratios that were either more than five standard deviations above or below the mean were considered outliers and not included in further calculations.

Because the results of a meta-analysis may depend on how individual studies are weighted40, we used one parametric and three different non-parametric weighting functions in our analyses. For every observation, weights were calculated by using the following functions:

-

1

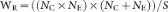

Weighting by the inverse of the pooled variance, the weighting function conventionally used in meta-analysis41:

where SDE and SDC are the standard deviations from the experimental and control groups, respectively; NE and NC are the sample sizes for the experimental and control groups, respectively; and E and C are the means of experimental and control groups, respectively.

-

2

Weighting by assigning an equal weight to each observation (unweighted):

where S is the total number of observations included in the study where the appointed observation came from.

-

3

Weighting by sample size:

where NE and NC are the sample sizes for the experimental and control groups, respectively and S is the total number of observations included in the study where the appointed observation came from.

-

4

Weighting by the inverse of the pooled variance, adjusted by the total number of observations in a certain study:

with VP as in weight #1) and S as the total number of observations included in the study where the appointed observation came from.

In the parametric meta-analysis (that is, using weight #1), each individual observation was weighted by the reciprocal of the mixed-model variance, which was the sum of the variance of the natural log of the response ratio and the pooled within-class variance. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the mean effect sizes according to Hedges and Olkin41. To test whether controlling factors altered the effect of earthworm presence, the data were divided into subgroups as described above. To test whether mean effect sizes differed between subgroups, we used the approach by Curtis and Wang42. Briefly, the total heterogeneity (Qt) was partitioned into within-class heterogeneity (Qw) and between class heterogeneity (Qb). Data were then subdivided according to levels of those categorical variables revealing significant Qb values (Supplementary Tables 2–5).

For the non-parametric analyses (that is, weights #2–4), we generated mean effect sizes and 95% CIs by running a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 iterations. The results for the analyses on ln R (mean effects and CIs) were back-transformed and reported as percentage change of the earthworm effect ([R-1]*100) to ease interpretation. For both the non-parametric and the parametric analyses, the mean earthworm effect was considered significant when the 95% confidence interval did not overlap with 0. Mean earthworm effects for different subgroups were considered to be significantly different from one another if their 95% confidence intervals did not overlap. For the parametric analyses, both the heterogeneity test had to indicate significance and the 95% CIs of study categories had to show no overlap for us to conclude that a categorical variable had a significant impact on the earthworm effect.

The potential for publication bias in this quantitative review was examined through a normal quantile plot. Normal quantile plots were produced for two main response variables, crop yield and aboveground biomass, because the results of this review are mainly based on analyses of these two response variables (Supplementary Fig. 1 & 2). Additionally, Rosenthal's method for calculation of a fail-safe number was added to the plots, indicating the number of non-significant, unpublished, or missing studies that would need to be added to the meta-analysis to change the results from significant to nonsignificant43. Both normal quantile plots as well as the fail-safe numbers suggest that our observed results can be treated as a reliable estimate of the true effect. All analyses were performed in METAWIN 2.144.

References

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812–818 (2010).

Royal Society of London. Reaping the benefits: Science and the sustainable intensification of global agriculture. (Royal Society, London, 2009).

Hobbs, P. R., Sayre, K. & Gupta, R. The role of conservation agriculture in sustainable agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 363, 543–555 (2008).

Seufert, V., Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 485, 229–U113 (2012).

Lubbers, I. M. et al. Greenhouse-gas emissions from soils increased by earthworms. Nature Clim. Change 3, 187–194 (2013).

Blouin, M. et al. A review of earthworm impact on soil function and ecosystem services. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 64, 161–182 (2013).

White, G. in The life and letters of Gilbert White of Selborne Vol. 1 (ed Holt-White R.) (John Murray, 1901).

Darwin, C. The formation of vegetable mould through the action of worms with observations on their habits. (Murray, 1881).

Brown, G. G. et al. in Earthworm management in tropical agroecosystems (eds Lavelle P., Brussaard L. & Hendrix P. F.), 87–147 (CABI Publishing, 1999).

Scheu, S. Effects of earthworms on plant growth: patterns and perspectives. Pedobiologia 47, 846–856 (2003).

Poorter, H. & Nagel, O. The role of biomass allocation in the growth response of plants to different levels of light, CO2, nutrients and water: a quantitative review. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 27, 595–607 (2000).

Brown, G. G., Edwards, C. A. & Brussaard, L. in Earthworm ecology. 2nd Edition. (ed Edwards C. A.) Ch. 2, 441 (CRC Press, 2004).

Jana, U. et al. Earthworms influence the production of above- and belowground biomass and the expression of genes involved in cell proliferation and stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 244–252 (2010).

Blouin, M. et al. Belowground organism activities affect plant aboveground phenotype, inducing plant tolerance to parasites. Ecol. Lett. 8, 202–208 (2005).

Puga-Freitas, R., Barot, S., Taconnat, L., Renou, J. P. & Blouin, M. Signal Molecules Mediate the Impact of the Earthworm Aporrectodea caliginosa on Growth, Development and Defence of the Plant Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One 7, 10 (2012).

Blair, J. M., Parmelee, R. W., Allen, M. F., McCartney, D. A. & Stinner, B. R. Changes in soil N pools in response to earthworm population manipulations in agroecosystems with different N sources. Soil Biol. Biochem. 29, 361–367 (1997).

Postma-Blaauw, M. B. et al. Earthworm species composition affects the soil bacterial community and net nitrogen mineralization. Pedobiologia 50, 243–256 (2006).

Kuczak, C. N., Fernandes, E. C. M., Lehmann, J., Rondon, M. A. & Luizão, F. J. Inorganic and organic phosphorus pools in earthworm casts (Glossoscolecidae) and a Brazilian rainforest Oxisol. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 553–560 (2006).

Le Bayon, R. C. & Milleret, R. Effects of earthworms on Phosphorus dynamics - a review. Dyn. Soil Dyn. Plant 3, 21–27 (2009).

Whalen, J. K., Parmelee, R., McCartney, D. A. & Vanarsdale, J. L. Movement of N from decomposing earthworm tissue to soil, microbial and plant N pools. Soil Biol. Biochem. 31, 487–492 (1999).

Edwards, C. A. & Lofty, J. R. Effects of earthworm inoculation upon the root-growth of direct drilled cereals. J. Appl. Ecol. 17, 533–543 (1980).

Hopp, H. & Slater, C. S. Influence of earthworms on soil productivity. Soil Sci. 66, 421–428 (1948).

Spurgeon, D. J., Keith, A. M., Schmidt, O., Lammertsma, D. R. & Faber, J. H. Land-use and land-management change: relationships with earthworm and fungi communities and soil structural properties. BMC Ecol. 13, 46 (2013).

Lavelle, P. et al. Soil invertebrates and ecosystem services. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 42, S3–S15 (2006).

Feller, C., Blanchart, E., Bernoux, M., Lal, R. & Manlay, R. Soil fertility concepts over the past two centuries: the importance attributed to soil organic matter in developed and developing countries. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 58, S3–S21 (2012).

Lavelle, P., Barois, I., Martin, A., Zaidi, Z. & Schaefer, R. in Ecology of arable land: perspectives and challenges (eds Clarholm M. & Bergstrom L.), 109–122 (Kluwer Academic Press, 1989).

Lavelle, P. et al. SOM management in the tropics: Why feeding the soil macrofauna? Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 61, 53–61 (2001).

Palm, C. A., Gachengo, C. N., Delve, R. J., Cadisch, G. & Giller, K. E. Organic inputs for soil fertility management in tropical agroecosystems: application of an organic resource database. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 83, 27–42 (2001).

Chan, K. Y. An overview of some tillage impacts on earthworm population abundance and diversity - implications for functioning in soils. Soil Till. Res. 57, 179–191 (2001).

Bai, E. et al. A meta-analysis of experimental warming effects on terrestrial nitrogen pools and dynamics. New Phytol. 199, 441–451 (2013).

Fu, R. et al. Handling continuous outcomes in quantitative synthesis. Methods guie for comparative effectiveness reviews. AHRQ Publication No.13-EHC103-EF. (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013).

Bouché, M. B. in Soil organisms as components of ecosystems Ecological Bulletins (eds Lohm U. & Persson E.), 122–132 (Swedish Natural Science Research Council, 1977).

Fragoso, C. et al. in Earthworm management in tropical agroecosystems (eds Lavelle P., Brussaard L. & Hendrix P. F.), 27–55 (CABI, 1999).

Didden, W. A. M. Earthworm communities in grasslands and horticultural soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 33, 111–117 (2001).

Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy. 8th edn, (United States Department of Agriculture, 1998).

Hodge, A., Robinson, D. & Fitter, A. Are miroorganisms more effective than plants at competing for nitrogen? Trends in Plant Science 5, 304–308 (2000).

Van Groenigen, K. J. et al. Element interactions limit soil carbon storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6571–6574 (2006).

Lal, R. The role of residues management in sustainable agricultural systems. J. Sustain. Agric. 5, 51–78 (1995).

Hedges, L. V., Gurevitch, J. & Curtis, P. S. The meta-analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80, 1150–1156 (1999).

Hungate, B. A. et al. Assessing the effect of elevated carbon dioxide on soil carbon: A comparison of four meta-analyses. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 2020–2034 (2009).

Hedges, L. V. & Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-analysis. (Academic Press, 1985).

Curtis, P. S. & Wang, X. A meta-analysis of elevated CO2 effects on woody plant mass, form and physiology. Oecologia 113, 299–313 (1998).

Rosenthal, R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 86, 638–641 (1979).

Rosenberg, M. S. B., Adams, D. C. & Gurevitch, J. Metawin: Statistical Software for Meta-Analysis, Version 2.0. (Sinauer Associates, 2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Bonkowski, Nico Eisenhauer, Patrick Lavelle, Olaf Schmidt and Nicole Schon for providing us with extra data on their published experiments. We are grateful to Ron de Goede for help in collecting the data and to Lijbert Brussaard for commenting on an earlier version of this manuscript. This study was funded through a personal VIDI grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research/Earth and Life Sciences (NWO-ALW) to J.W.v.G. (project number 864.07.004). K.J.v.G. receives financial support from the Office of Science (BER), U.S. Department of Energy. Additional funding was provided by CPNq to G.G.B. and through a VIDI grant from NWO-ALW to G.B.D.D. (project number 864.11.003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W.v.G., I.M.L. and K.J.v.G. conceived the study. H.M.J.V. and J.W.v.G. extracted the data from the literature. I.M.L. performed the meta-analysis. G.G.B. and G.B.D.D. contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data. J.W.v.G., I.M.L. and K.J.v.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. J.W.v.G. was overall project leader.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Earthworms increase plant production: a meta-analysis

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

van Groenigen, J., Lubbers, I., Vos, H. et al. Earthworms increase plant production: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 4, 6365 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06365

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06365

This article is cited by

-

Artificial light at night reduces earthworm activity but increases growth of invasive ragweed

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2024)

-

Climate-dependent plant responses to earthworms in two land-use types

Oecologia (2024)

-

Non-native earthworms increase the abundance and diet quality of a common woodland salamander in its northern range

Biological Invasions (2024)

-

Earthworms do not increase greenhouse gas emissions (CO2 and N2O) in an ecotron experiment simulating a three-crop rotation system

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Augmentation of plant biomass productivity using epigeic earthworm Perionyx excavatus and Eisenia fetida as soil nutrient facilitators

Scientific Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.