Abstract

Oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) with different oxygen contents were investigated for the adsorption of tetracycline (TC) from aqueous solutions. As the surface oxygen content of the MWCNTs increased, the maximum adsorption capacity and adsorption coefficient of TC increased to the largest values and then decreased. The relation can be attributed to the interplay between the nanotubes' dispersibility and the water cluster formation upon TC adsorption. The overall adsorption kinetics of TC onto CNTs-3.2%O might be dependent on both intra-particle diffusion and boundary layer diffusion. The maximum adsorption capacity of TC on CNTs-3.2%O was achieved in the pH range of 3.3–8.0 due to formation of water clusters or H-bonds. Furthermore, the presence of Cu2+ could significantly enhanced TC adsorption at pH of 5.0. However, the solution ionic strength did not exhibit remarkable effect on TC adsorption. In addition, when pH is beyond the range (3.3–8.0), the electrostatic interactions caused the decrease of TC adsorption capacity. Our results indicate that surface properties and aqueous solution chemistry play important roles in TC adsorption on MWCNTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibiotics are used extensively in human therapy and livestock husbandry. Approximately 70% of annual antibiotic consumption is associated with agriculture, animal husbandry and aquaculture1. Residual antibiotics enter surface water and groundwater through surface runoff, leaching and other pathways1. The antibiotic tetracycline (TC, C22H24N2O8) exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial activities by blocking DNA replication enzymes and inhibiting bacterial growth. TC has recently become a serious environmental concern4, as incompletely metabolised TC has been detected in both wastewater sludge-treated agricultural soils and in surface waters affected by effluents from wastewater treatment plants2,3. Hence, the removal of TC is of great interest. The adsorption of TC by different sorbents, such as graphene oxide4, aluminium oxide5, Fe-Mn binary oxide6 and montmorillonite7, is considered the easiest and most economical available treatment.

More efficient and cost-effective novel adsorbents are urgently needed and are the focus of intense development. Recent studies have demonstrated that carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can be used as effective adsorbent materials to remove organic contaminants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, chlorinated benzenes and antibiotics because of the strong hydrophobic nature and unique graphitic structure of CNTs, which permit specific π-electron-related interactions8,9,10,11. Sun et al.12 have investigated the adsorption of diuron, fluridone and norflurazon by single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs) and three multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs), including MWCNTs10 (<10 nm, outer diameter), MWCNTs20 (10–20 nm) and MWCNTs40 (20–40 nm). Carabineiro et al.8 investigated the adsorption of ciprofloxacin on three types of carbon materials, including activated carbon (AC), CNTs and carbon xerogel. The adsorption behaviour and mechanisms of adsorption of norfloxacin on porous resins and CNTs were studied by Yang et al.13. Zhang et al.1 studied the removal of TC by MWCNTs under different conditions (pH, ionic strength, adsorbent amount, adsorption time and temperature). Ji et al.14 demonstrated the importance of aqueous solution conditions (ionic strength: NaCl and CaCl2, Cu2+, humic acids) for TC adsorption on carbon nanotubes. A systematic study of the adsorption process of TC15 revealed an adsorption mechanism involving non-electrostatic π-π dispersion interactions and hydrophobic interactions between TC and MWCNTs. Ji et al.16 have reported that the adsorption affinity of TC decreases in the following order: graphite/SWCNTs > MWCNTs ≫ AC.

While most reports have primarily focused on the influence of aqueous solution chemistry on the adsorption capacity and properties of TC, few relevant studies have investigated the adsorption behaviour of antibiotics on CNTs with different oxygen contents or assessed the antibiotic adsorption capacity of CNTs. The toxicity of CNTs may be further increased by the adsorption of toxic chemicals. Thus, an understanding of organic chemical adsorption by CNTs is critical for the assessment of the environmental risk of CNTs and toxic chemicals.

In the present work, we investigate the adsorption of TC to MWCNTs with different oxygen contents to optimise the adsorption of pollutants. TC is the second most widely produced and used antibiotic worldwide, and, in particular, in China17. To delineate and compare the influences of CNT surface properties and aqueous solution chemistry on the adsorption of TC, we examined different solution conditions (pH, ionic strength and the presence of Cu2+) and MWCNTS with different oxygen contents. We observed that the maximum adsorption capacity and adsorption coefficient of TC increased initially and then decreased with increasing CNT surface oxygen content. This variation in adsorption capacity is attributable to the interplay between nanotube dispersibility and water cluster formation upon TC adsorption.

Methods

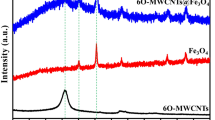

Sorbents

MWCNTs were produced by the catalytic chemical vapour deposition method at 1000–1150°C using ethanol as the carbon feedstock, ferrocene as a catalyst and thiophene as a growth promoter18. The as-prepared samples were purified by a non-destructive approach19 to remove impurities such as Fe nanoparticles and amorphous carbon. Then, the MWCNTs were oxidised by various concentrations of sodium hypochlorite, as described previously20. The detailed properties of the three MWCNTs with different oxygen contents have been described20. Based on their oxygen content, the different MWCNTs used in this study were termed CNTs-2.0%O, CNTs-3.2%O, CNTs-4.7%O and CNTs-5.9%O. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas of CNTs-2.0%O, CNTs-3.2%O, CNTs-4.7%O and CNTs-5.9%O were 471, 381, 382 and 327 m2/g, respectively, as shown in Table S1.

Adsorption experiments

All adsorption experiments were conducted in 50 mL glass vials containing 20 mg of MWCNTs and 40 mL of TC solution. To obtain adsorption isotherms, 40 mL samples of TC solutions of increasing concentrations (7.3–151.6 mg/L) were placed in contact with 20 mg of the adsorbent. The suspensions were then shaken on a rotary shaker (TS-2102C, Shanghai, China) at 150 r/min for 24 h at 298 K. Upon reaching adsorption equilibrium, the suspensions were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter membrane. The TC concentration was analysed with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UV759UV-VIS) at 357.2 nm using a calibration curve constructed using TC solutions of different concentrations. Blank experiments without the addition of adsorbents were also conducted to confirm that no adsorption occurred on the glass vial wall.

To investigate the kinetics of TC adsorption, each glass vial containing 20 mg of MWCNTs was filled with 40 mL of a 133.8 mg/L TC solution at 298 K. At regular time intervals, the suspension was filtered and the TC concentration was analysed.

Separate sets of experiments were conducted to test the effects of pH and ionic strength on single-point adsorption to the MWCNTs. The pH levels of the solutions were adjusted to the designated values (2, 4, 6, 8, 10) using 0.01 M HCl or 0.01 M NaOH. The TC concentration was 128.5 mg/L and the temperature was maintained at 298 K. To determine the effects of ionic strength, the adsorption assays were performed using control solutions of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.4 M NaCl with a TC concentration of 138.2 mg/L and a temperature of 298 K.

The amount of adsorbed TC (qe, mg/g) was calculated as follows:

where C0 and Ce are the initial and equilibrium TC concentrations (mg/L), respectively, V is the initial solution volume (L) and m is the adsorbent weight (g).

Results

Equilibrium adsorption isotherms

The amount of TC adsorbed at equilibrium to MWCNTs with varying oxygen contents at different TC concentrations is depicted in Figure 1a. We used two typical adsorption models (the Langmuir and Freundlich models) to fit the experimental equilibrium adsorption data. The Langmuir and Freundlich models are expressed as follows:

where qm is the maximum adsorption capacity and Kl is the Langmuir adsorption equilibrium constant (L/mg). Kf and n are Freundlich constants related to the adsorption capacity ((mg/g)(L/mg)n) and adsorption intensity (dimensionless) of the adsorbents, respectively. The Langmuir and Freundlich fits are shown in Figure 1(b–c) and the regression data for the three models for all adsorbents are listed in Table 1.

The maximum adsorption capacities (qm) calculated by the Langmuir model were 217.8, 269.25, 217.56 and 210.43 mg/g for CNTs-2.0%O, CNTs-3.2%O, CNTs-4.7%O and CNTs-5.9%O, respectively. As shown in Figure 2a, the order of the qm values for TC adsorption was as follows: CNTs-2.0%O < CNTs-3.2%O > CNTs-4.7%O > CNTs-5.9%O. The maximum adsorption capacities strongly correlated with the extent of surface oxidation and did not change monotonically with increasing levels of oxidation. With increasing surface oxygen content, the maximum adsorption capacity of TC initially increased and then began to decrease. Similar results have been reported previously for the absorption of different organic compounds (toluene, ethylbenzene and m-xylene) on purified and oxidised MWCNTs20.

(a) Maximum adsorption capacity (qm) and adsorption coefficient (Kd) of TC as a function of the surface oxygen concentration of the MWCNTs. (b) Correlation of the BET-normalised maximum adsorption capacity (qm/BET) and of the adsorption coefficients (Kd/BET) for TC with the surface oxygen concentration. Kd was calculated from the Langmuir adsorption model at Ce = 0.1 Sw and 0.01 Sw.

To elucidate the adsorption mechanism, the Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm model21,22 was used to estimate the porosity, apparent free energy and the characteristics of adsorption on both homogenous and heterogeneous surfaces. The linear form of the D-R model can be expressed as follows:

where B is a constant related to the mean free energy of adsorption (mol2/kJ2); qm is the theoretical saturation capacity in mg/g; ε is the Polanyi potential, which can be determined from Eq. (5); and Ea is the mean free energy of adsorption, defined as the free energy change when one mole of ion is transferred from infinity in solution to the surface of the adsorbent. The values of Ea can be calculated by Ea = 1/(2B)1/2.

The values of the adsorption energy (Ea) calculated by the D-R model were 0.96, 9.28, 13.36 and 16.67 kJ/mol for CNT-2.0%O, CNT-3.2%O, CNT-4.7%O and CNT-5.9%O, respectively, values that do not correspond to the chemical adsorption energies, i.e., 20–40 kJ/mol23. As the oxygen content increased, the values of Ea gradually increased from 0.96 to 16.67 kJ/mol (Table 1). Hence, the TC adsorption process may change from physical adsorption to chemical adsorption with increasing MWCNT oxygen content. However, given the low R2 value, further studies are needed to verify this conclusion. Within the range of tested concentrations, the coefficients of determination (R2) for the Langmuir, Freundlich and D-R models for TC adsorption were 0.941–0.986, 0.880–0.984 and 0.858–0.987, respectively. Further studies will provide additional insights into the adsorption mechanism.

Based on a comparison of the R2 values, the Langmuir model may be most suitable for simulating the TC adsorption isotherm data. The adsorption affinities of TC for MWCNTs with different oxygen contents are also reflected by the adsorption coefficient (Kd)11, which is calculated from the Langmuir model using equilibrium concentrations at Ce = 0.1 Sw, 0.01 Sw, as shown in Figure 2a. Based on the physicochemical properties of MWCNTs, the trends in qm and Kd are not consistent with the changes in BET surface area, pore diameter, or pore volume. Because the BET surface area plays an important role in adsorption24 and thus the maximum adsorption capacity and adsorption coefficient were normalised using the BET surface area (qm/BET and Kd/BET) to analyse the influence of surface chemistry on TC adsorption. The correlations between qm/BET, Kd/BET and TC and the surface oxygen concentration are shown in Figure 2b. With increasing surface oxygen content, qm/BET and Kd/BET initially increased, then began to decrease. The results in Figure 2b reveal that a 60% increase in oxygen concentration, from 2.0% to 3.2%, led to 51.88%, 43.21% and 52.82% increases in Kd/BET (Ce = 0.1 Sw), Kd/BET (Ce = 0.01 Sw) and qm/BET, respectively. More interestingly, a 46.9% increase in the oxygen concentration from 3.2% to 4.7% led to 5.73%, 4.63% and 5.85% decreases in Kd/BET (Ce = 0.1 Sw), Kd/BET (Ce = 0.01 Sw) and qm/BET, respectively. However, a 25.5% increase in the oxygen concentration from 4.7% to 5.9% led to 17.03%, 15.51% and 17.20% decreases in Kd/BET (Ce = 0.1 Sw), Kd/BET (Ce = 0.01 Sw) and qm/BET, respectively. If we assume that the change is linear, when the oxygen contents of the MWCNTs are higher than roughly 6.83%, 6.82% and 6.77%, Kd/BET (Ce = 0.1 Sw), Kd/BET (Ce = 0.01 Sw) and qm/BET decrease relative to their values for MWCNTs with an oxygen content of 2.0%.

Adsorption kinetics

As shown in Figure 3a, the adsorption of TC on CNTs-3.2%O was rapid during the initial period (~10 min) and gradually slowed with increasing contact time, nearly reaching a plateau after approximately 80 min.

To investigate the process of adsorption of TC on CNT-3.2%O, pseudo-first-order kinetic, pseudo-second-order kinetic, intra-particle diffusion and Boyd plot models were used to fit the experimental data. The pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models are expressed by the following equations25,26:

where qe and qt are the amounts of TC adsorbed (mg/g) at equilibrium and time t (min), respectively and k1 is the rate constant of the pseudo-first-order kinetic model (1/min). The values of qe and k1 can be determined from the intercept and slope, respectively, of the linear plots of log(qe − qt) versus t. k2 is the rate constant (g/mg·min) of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model for adsorption. The straight-line plots of t/qt versus t were tested to obtain the rate parameters.

The intra-particle diffusion model is represented as follows27:

where C (mg/g) is the intercept and kid is the intra-particle diffusion rate constant (mg/g·min1/2), which can be calculated from the slope of the linear plots of qt versus t1/2.

The Boyd plot is obtained by plotting Bt versus time t, where Bt is expressed by the following equation:

where B = π2Di/r2 (Di is the effective diffusion coefficient of the adsorbate and r is the average radius of the adsorbent particles, which are assumed to be spherical).

Linear regressions of the kinetic plots are shown in Figure 3(b–e). The kinetic parameters and calculated initial adsorption rates are listed in Table 2. Based on the correlation coefficients (R2), the experimental data are best described by the pseudo-second-order model, which gave higher correlation coefficient values (R2 = 0.999). Moreover, the q values (qe,cal) calculated from the pseudo-second-order model were more consistent with the experimental q values (qe,exp) than those calculated by other models.

The adsorption process for porous solids can be divided into three stages: (1) external mass transfer of the adsorbate across the liquid film to the adsorbent exterior surface, which is also called outer diffusion (or boundary layer diffusion); (2) transport of the adsorbate from the adsorbent exterior surface to the pores or capillaries of the adsorbent internal structure, which is called intra-particle diffusion (or inner diffusion)28,29; and (3) adsorption of the adsorbate onto the active sites on the inner and outer surfaces of the adsorbent30. The third step is considered very fast and thus cannot be treated as the rate-controlling step. Generally, the adsorption rate is controlled by outer diffusion or intra-particle diffusion or both23,24.

Because the pseudo-second-order model cannot identify the diffusion mechanism during the adsorption process, the intra-particle diffusion model was used to determine the adsorption process of TC onto CNTs-3.2%O. According to Eq. (8), a plot of qt versus t1/2 should be linear if intra-particle diffusion is involved in the adsorption process. If the best-fit line passes through the origin, intra-particle diffusion is the rate-controlling step. Otherwise, intra-particle diffusion is not the only rate-controlling step and some degree of outer diffusion also controls the adsorption process. As observed in Figure 3d, although the regression was linear for TC adsorption, the plot did not pass through the origin, suggesting that intra-particle diffusion was not the sole rate-controlling step. Therefore, both intra-particle diffusion and outer diffusion may play important roles in the overall adsorption process.

It is clear that the rate- controlling step of TC adsorption on CNT-3.2%O involves complex processes, including outer diffusion and intra-particle diffusion. However, it was unclear which process exerted a greater influence on the rate of TC adsorption. This ambiguity was resolved using the Boyd plot1 (Figure 3e). The linearity of the plot provides useful information for distinguishing between outer diffusion and intra-particle diffusion control mechanisms. If the plot passes through the origin, intra-particle diffusion controls the rate of mass transfer. The plot in Figure 3e does not pass through the origin, confirming the involvement of outer diffusion throughout the adsorption process1. This result further confirmed the rate-controlling mechanism of adsorption as stated in the intra-particle diffusion kinetic model studies. Therefore, the overall adsorption process was jointly controlled by intra-particle diffusion and outer diffusion.

Effects of solution pH on the adsorption of TC on CNTs-3.2%O

TC is an amphoteric molecule with three protonated functional groups: tricarbonyl methane group, phenolic deketone group and dimethylamino group31. The pH value can affect the protonation state of the TC molecule as well as the physiochemical properties of the adsorbate (charge and hydrophobicity), thus influencing the adsorptive interactions on the carbon nanotube surface. In aqueous solutions, the three groups can undergo protonation–deprotonation reactions and form cationic species (pH < 3.3), zwitterionic species (3.3 < pH < 7.68), or anionic species (pH > 7.68)31. To gain further insight into the adsorption process, the effects of initial pH on the removal ratio and adsorption capacity of TC by CNTs-3.2%O were studied; the results are presented in Figure 4. The maximum adsorption capacity occurred in the pH range 3.3–8.0, which corresponds to the zwitterionic form of the TC molecule. The adsorption capacity for TC decreased when the pH was less than 3.3 or greater than 8, at which TC has either positive or negative net charges, respectively. In this study, the maximum adsorption capacity for TC was observed at pH 4. The removal ratio exhibited the same trend as the maximum adsorption capacity.

CNTs-3.2%O has an overall negative surface charge at pH 2–1020,32. At solution pH > 8, both CNTs-3.2%O and TC are negatively charged and electrostatic repulsion may become a dominant interaction force, resulting in low adsorption. When the solution pH is < 3.3, the TC molecules and the CNTs-3.2%O surface have opposite charges and thus adsorption is expected to be enhanced, consistent with the experimental data. Therefore, electrostatic attraction between TC and CNTs-3.2%O was one of the major factors controlling the adsorption process. At pH values between 3.3 and 8.0, TC exists as a zwitterion. Under these conditions, nearly all of the TC molecules carry no net electrical charge, resulting in reduced electrostatic attraction or repulsion between TC and CNTs-3.2%O. The increase in solution pH led to increased hydrophilicity and reduced hydrophobic interactions. It also enhanced the formation of water clusters and reduced the formation of H-bonds. The water clusters may have hindered the adsorption of TC onto CNTs-3.2%O. Consequently, the dominant adsorption mechanisms are most likely electrostatic interactions between TC and CNTs-3.2%O, π-π interactions between the MWCNT surface and the benzene rings and double bonds (C = C, C = O) of the TC molecules, or hydrophobic interactions between CNTs-3.2%O and TC. Further research is required to evaluate the different adsorption interactions for TC adsorption onto CNTs-3.2%O.

Effects of Cu2+ on the adsorption of TC on CNTs-3.2%O

The introduction of heavy metals into the environment creates potential risks associated with their impact on environmental quality and human health. Because copper concentrations in some animal wastes are elevated due to the use of copper as a growth promoter in animal feed, copper and TC can coexist in the environment. Hence, copper was chosen in this study as a representative heavy metal. As shown in Figure 5, the TC adsorption capacity increased in the presence of Cu2+ compared to that in the absence of Cu2+ at pH 5. Similar observations have been reported previously for the adsorption of TC onto MWCNTs, montmorillonite and chitosan in the presence of copper31,33,34,35. Under the tested conditions (pH 5.0 ± 0.2), TC is predominantly in the zwitterionic form, which contains a deprotonated hydroxyl group and an amide group that enables Cu2+ coordination. Cu2+ can also strongly bind with the carboxyl and hydroxyl groups on the surface of CNTs-3.2%O through ligand-exchange reactions. Therefore, ternary complexes are expected to form among the Cu2+, TC and CNT functional groups, resulting in Cu2+-enhanced TC adsorption to CNTs-3.2%O through cation bridging between the metal ion and TC and the adsorbent ligand groups.

Effects of ionic strength on the adsorption of TC to CNTs-3.2%O

Ionic strength is one factor controlling both electrostatic and non-electrostatic interactions between the adsorbate and the adsorbent surface. Figure 6 exhibits the effects of the solution ionic strength on the TC adsorption capacity and removal ratio by CNTs-3.2%O. The adsorption capacities for TC were not significantly affected by increasing the NaCl concentration from 0 to 0.4 M, reflecting the high stability of CNTs-3.2%O as a TC adsorbent across a wide range of solution ionic strengths. The qe values of TC slightly decreased as the ionic strength increased from 0 to 0.1 M and then slightly increased from 0.1 to 0.4 M and the trend of the removal ratio of TC by CNTs-3.2%O was identical to that for the adsorption capacity. This indicates that chloride ions do not compete with the functional groups of TC for CNTs-3.2%O. These results indicate that CNTs-3.2%O can be used for the removal of TC from salt-containing water.

Discussion

The maximum adsorption capacity of the MWCNTs was strongly correlated with the extent of surface oxidation. The adsorption of TC initially increased and then began to decrease with increasing surface oxygen content. Previous studies on the adsorption mechanism of TC to carbon nanotubes are very limited. It is generally believed14,16 that the surfaces of carbon nanotubes bind TC tightly because the enone structures and protonated amino group of TC can strongly interact with the polarised electron-rich graphene structures of carbon nanotubes through π-π electron-donor-acceptor (EDA) interactions and cation-π bonding, respectively. However, the EDA interaction mechanism does not explain our experimental results. Therefore, we speculate that dispersibility and water cluster formation on the MWCNT surface play important roles in TC adsorption. The oxygen content of the MWCNTs was first increased from 2.0% to 3.2% to improve the hydrophilicity and dispersibility of the MWCNTs in aqueous solutions. The improved dispersion of the MWCNTs in water increased the number of available adsorption sites, which consequently facilitated aqueous phase adsorption. Therefore, the adsorption affinity was significantly enhanced and dispersive interactions were predominant. When the surface oxygen concentration was increased from 3.2% to 5.9%, a lower TC adsorption capacity was observed compared with that of CNTs-3.2%O, although the adsorption capacity was still higher than that of CNTs-2.0%O. Although the dispersion was improved by surface functionalisation in aqueous solution, the adsorption affinity for TC decreased substantially due to water cluster formation caused by the phenolic groups introduced on the surface or tube ends of the MWCNTs through hydrogen bonding at hydrophilic sites, in agreement with Wang's report36,37. For CNTs-4.7%O, dispersion played a more important role than water cluster formation and thus the adsorption was considerably higher than that of CNTs-2.0%O. When the oxygen concentration was increased further (CNTs-5.9%O), water cluster formation played a more important role in TC adsorption than did dispersion and thus the adsorption affinity for TC was lower than that of CNTs-2.0%O. Decreases in the adsorption of naphthalene38, perfluorooctane sulphonate39 and phenanthrene40 after oxidation of CNTs have also been reported.

Conclusions

MWCNTs were oxidised to produce nanotubes with different oxygen contents, which acted as adsorbents for TC in aqueous solutions. As the MWCNT oxygen content increased from 2.0% to 5.9%, the maximum adsorption capacities (qm) for TC adsorption were as follows: CNTs-2.0%O < CNTs-3.2%O > CNTs-4.7%O > CNTs-5.9%O. This can be attributed to the co-influences of dispersibility and water cluster formation on TC adsorption on MWCNTs. Kinetic studies suggested that the binding equilibrium was achieved within only 10 min and that a pseudo-second-order kinetic model was followed. The different kinetic models indicated that both intra-particle diffusion and outer diffusion were involved in the overall adsorption process. This study also compared the influence of aqueous solution chemistry (pH, ionic strength and the presence of Cu2+) on the adsorption of TC. In summary, our results indicate that the surface properties of MWCNTs (surface oxygen content) and aqueous solution chemistry play important roles in TC adsorption to MWCNTs. Optimal conditions were obtained with the use of CNTs-3.2%O at a pH range of 3.0–8.0.

References

Zhang, L. et al. Studies on the removal of tetracycline by multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 178, 26–33 (2011).

Beausse, J. Selected drugs in solid matrices: a review of environmental determination, occurrence and properties of principal substances. Trac-Trend Anal. Chem. 23, 753–761 (2004).

Golet, E. M., Strehler, A., Alder, A. C. & Giger, W. Determination of fluoroquinolone antibacterial agents in sewage sludge and sludge-treated soil using accelerated solvent extraction followed by solid-phase extraction. Anal. Chem. 74, 5455–5462 (2002).

Gao, Y. et al. Adsorption and removal of tetracycline antibiotics from aqueous solution by graphene oxide. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 368, 540–546 (2012).

Chen, W.-R. & Huang, C.-H. Adsorption and transformation of tetracycline antibiotics with aluminum oxide. Chemosphere 79, 779–785 (2010).

Liu, H. et al. Removal of tetracycline from water by Fe-Mn binary oxide. J. Environ. Sci. 24, 242–247 (2012).

Parolo, M. E., Avena, M. J., Pettinari, G. R. & Baschini, M. T. Influence of Ca2+ on tetracycline adsorption on montmorillonite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 368, 420–426 (2012).

Carabineiro, S. A. C., Thavorn-Amornsri, T., Pereira, M. F. R. & Figueiredo, J. L. Adsorption of ciprofloxacin on surface-modified carbon materials. Water Res. 45, 4583–4591 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. Adsorption behaviour of multi-walled carbon nanotubes for the removal of olaquindox from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 197, 389–396 (2011).

Hu, J. L. et al. Adsorption of roxarsone from aqueous solution by multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 377, 355–361 (2012).

Ji, L. L. et al. Adsorption of Monoaromatic Compounds and Pharmaceutical Antibiotics on Carbon Nanotubes Activated by KOH Etching. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 6429–6436 (2010).

Sun, K. et al. Adsorption of diuron, fluridone and norflurazon on single-walled and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Sci. Total. Environ. 439, 1–7 (2012).

Yang, W. et al. Adsorption behavior and mechanisms of norfloxacin onto porous resins and carbon nanotube. Chem. Eng. J. 179, 112–118 (2012).

Ji, L. L. et al. Adsorption of Tetracycline on Single-Walled and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes as Affected by Aqueous Solution Chemistry. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29, 2713–2719 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Studies on the removal of tetracycline by multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 178, 26–33 (2011).

Ji, L. L., Chen, W., Duan, L. & Zhu, D. Q. Mechanisms for strong adsorption of tetracycline to carbon nanotubes: A comparative study using activated carbon and graphite as adsorbents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 2322–2327 (2009).

Wan, Y., Bao, Y. Y. & Zhou, Q. X. Simultaneous adsorption and desorption of cadmium and tetracycline on cinnamon soil. Chemosphere 80, 807–812 (2010).

Ma, J., Wang, J. N. & Wang, X. X. Large-diameter and water-dispersible single-walled carbon nanotubes: synthesis, characterization and applications. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 3033–3041 (2009).

Wang, J. N. & Ma, J. Purification of single-walled carbon nanotubes by a highly efficient and nondestructive approach. Chem. Mater. 20, 2895–2902 (2008).

Yu, F., Ma, J. & Wu, Y. Q. Adsorption of toluene, ethylbenzene and m-xylene on multi-walled carbon nanotubes with different oxygen contents from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 192, 1370–1379 (2011).

Hsieh, C. T. & Teng, H. S. Langmuir and Dubinin-Radushkevich analyses on equilibrium adsorption of activated carbon fabrics in aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 75, 1066–1072 (2000).

Chen, S. G. & Yang, R. T. Theoretical Basis for the Potential-Theory Adsorption-Isotherms - the Dubinin-Radushkevich and Dubinin-Astakhov Equations. Langmuir 10, 4244–4249 (1994).

Yu, F., Wu, Y. Q., Li, X. M. & Ma, J. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies of Toluene, Ethylbenzene and m-Xylene Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions onto KOH-Activated Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 60, 12245–12253 (2012).

Ma, J. et al. Enhanced Adsorptive Removal of Methyl Orange and Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution by Alkali-Activated Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Acs Appl. Mater. Inter. 4, 5749–5760 (2012).

Ngah, W. S. W. & Fatinathan, S. Adsorption of Cu(II) ions in aqueous solution using chitosan beads, chitosan-GLA beads and chitosan-alginate beads. Chem. Eng. J. 143, 62–72 (2008).

Xiao, L., Zhu, H. Y., Jiang, R. & Zeng, G. M. Preparation, characterization, adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics of novel magnetic chitosan enwrapping nanosized gamma-Fe(2)O(3) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes with enhanced adsorption properties for methyl orange. Bioresource Technol. 101, 5063–5069 (2010).

Kavitha, D. & Namasivayam, C. Experimental and kinetic studies on methylene blue adsorption by coir pith carbon. Bioresource Technol. 98, 14–21 (2007).

Zogorski, J. S., Faust, S. D. & Haas Jr, J. H. The kinetics of adsorption of phenols by granular activated carbon. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 55, 329–341 (1976).

Ho, Y. S., Wase, D. A. J. & Forster, C. F. Kinetic studies of competitive heavy metal adsorption by sphagnum moss peat. Environ. Technol. 17, 71–77 (1996).

Basibuyuk, M. & Forster, C. F. An examination of the adsorption characteristics of a basic dye (Maxilon Red BL-N) on to live activated sludge system. Process Biochem. 38, 1311–1316 (2003).

Zhao, Y. P. et al. Adsorption of tetracycline (TC) onto montmorillonite: Cations and humic acid effects. Geoderma 183, 12–18 (2012).

Lu, C., Su, F. & Hu, S. Surface modification of carbon nanotubes for enhancing BTEX adsorption from aqueous solutions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 254, 7035–7041 (2008).

Kang, J. et al. Systematic study of synergistic and antagonistic effects on adsorption of tetracycline and copper onto a chitosan. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 344, 117–125 (2010).

Ji, L. et al. Adsorption of teteracycline on single-walled and multi-walled carbon nanotubes as affected b aqueous solution chemistry. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29, 2713–2719 (2010).

Wang, Y.-J. et al. Adsorption and cosorption of tetracycline and copper(II) on montmorillonite as affected by solution pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 3254–3259 (2008).

Wang, X., Liu, Y., Tao, S. & Xing, B. Relative importance of multiple mechanisms in sorption of organic compounds by multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 48, 3721–3728 (2010).

Kaneko, K. et al. Cluster-mediated water adsorption on carbon nanopores. Adsorption 5, 7–13 (1999).

Cho, H. H. et al. Influence of surface oxides on the adsorption of naphthalene onto multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 2899–2905 (2008).

Li, X. N. et al. Adsorption of ionizable organic contaminants on multi-walled carbon nanotubes with different oxygen contents. J. Hazard. Mater. 186, 407–415 (2011).

Zhang, S. J., Shao, T., Bekaroglu, S. S. K. & Karanfil, T. The Impacts of Aggregation and Surface Chemistry of Carbon Nanotubes on the Adsorption of Synthetic Organic Compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 5719–5725 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Scholarship Award for Excellent Doctoral Students granted by the Ministry of Education, the Shanghai Institute of Technology Scientific Research Foundation for Introduced Talent, China (No. YJ2014-30) and the central finance special fund to support the development of local colleges and universities (City Safety Engineering). This research was also supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21207100), the State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control and Resource Reuse Foundation (No. PCRRY11009), the Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project (No. J51503), “Shu Guang” Project (No. 11SG54) and Shanghai Talent Development Funding (No. 201335).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Y. and J.M. designed the experiments, analysed the data and co-wrote the paper. S.H. revised and reviewed the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supplementary info

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, F., Ma, J. & Han, S. Adsorption of tetracycline from aqueous solutions onto multi-walled carbon nanotubes with different oxygen contents. Sci Rep 4, 5326 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05326

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05326

This article is cited by

-

Formation of zinc oxide composites of doxycycline with high antibacterial activity based on DC-magnetron deposition of ZnO nanoscale particles on the drug surface

Applied Physics A (2024)

-

Effect of Oxyfluorination of Activated Carbon on the Adsorption of Tetracycline from Aqueous Solutions

Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering (2024)

-

Visible light-driven photocatalytic removal of tetracycline healthcare waste by retrievable ZnFe2O4/MWCNTs nanocomposite

Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (2024)

-

Cellulose nanocrystals from orange and lychee biorefinery wastes and its implementation as tetracycline drug transporter

Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery (2023)

-

Adsorption Characteristics and Mechanisms of Oxytetracycline on Nano Biochar: Effects of Environmental Conditions and Particle Aggregation

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.