Abstract

We report a daily-updated sequenced/species Tree Of Life (sTOL) as a reference for the increasing number of cellular organisms with their genomes sequenced. The sTOL builds on a likelihood-based weight calibration algorithm to consolidate NCBI taxonomy information in concert with unbiased sampling of molecular characters from whole genomes of all sequenced organisms. Via quantifying the extent of agreement between taxonomic and molecular data, we observe there are many potential improvements that can be made to the status quo classification, particularly in the Fungi kingdom; we also see that the current state of many animal genomes is rather poor. To augment the use of sTOL in providing evolutionary contexts, we integrate an ontology infrastructure and demonstrate its utility for evolutionary understanding on: nuclear receptors, stem cells and eukaryotic genomes. The sTOL (http://supfam.org/SUPERFAMILY/sTOL) provides a binary tree of (sequenced) life and contributes to an analytical platform linking genome evolution, function and phenotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

DNA sequencing technologies have been generating a massive amount of data from a wide range of cellular organisms1,2. These information-rich, cross-species genomic data offer unprecedented opportunities for biomedical research, often better understood in the light of evolution. What the sequence-derived species tree of life (sTOL) looks like, is a grand challenge upon which there is no unanimous agreement so far, but there is an increasing consensus on using whole genomes. In line with growing amounts of genomic data, phylogenomics using genome-scale information to infer evolutionary relationships is becoming more and more popular3. For instance, trees can be reconstructed using genomic features, such as gene content4,5 and protein structure information6,7,8,9. An obvious advantage of using these genome-scale features is that they are less sensitive to non-phylogenetic signals and random artifacts than using individual features10. Another concern for phylogenomics is the taxonomic sampling. Wider sampling tends to reduce the impact of long-branch attraction, particularly for clades with a much smaller number of species11. Owing to rapid genome-sequencing technologies, the access to rich species samples may be the key toward a highly resolved sTOL regardless of methods used.

In theory, phylogenomics aimed at producing sTOL can be applied to any genomic features that are of evolutionary relevance. Ideally, genomic features under consideration should act both as conserved fingerprints and as discriminative characters. Largely due to advances in protein structure classification12 and profile hidden Markov models (HMMs)13, protein domain compositions are now particularly worth investigating for this purpose. First, 3D domains are not only the structural unit, but also the evolutionary unit. Due to evolutionary pressure, domains diverge far more slowly than their primary sequences. The Structural Classification of Proteins (SCOP) database14 hierarchically classifies protein domains into class, fold, superfamily and family levels. At the superfamily (or evolutionary) level, domains are grouped together if there is evidence for a common evolutionary ancestor; domains within the same superfamily are further divided into the family level, also in an evolutionarily consistent manner15. SCOP domains classified at these two different granularities of evolutionary relatedness are suitable for the use in phylogenomic analysis. Second, SCOP domains at the superfamily and family levels are relatively stable as phylogenetic fingerprints. Although the proteins of newly solved structures continues to increase exponentially in number16, the number of new superfamilies and families is trivial from one update to the next17, suggesting that the repertoire of protein modular designs evolves at an extremely slow rate. Third, domain assignments for sequenced genomes are routinely available. The latest version of the SUPERFAMILY database18 provides SCOP domain assignments for nearly 2,500 genomes at both the superfamily19 and family20 levels. Each protein sequence in the SUPERFAMILY database is represented as a sequential order of SCOP superfamily domains, called a domain architecture21. Such representation allows the use of combinatorial information in further refining relationships among the closely related species. The combination of two or more domains into ‘supra-domains’22 is meaningful in evolution. As larger evolutionary units, supra-domains are assumedly considered as a major contributor to organismal complexity and thus are informative for distinguishing complex multicellular organisms. Last but not least, domains (and domain architectures) are thought to be more tolerant to homoplasy than their counterpart genes/proteins23,24 and are thus better suited for phylogenetic analyses. For these reasons above, we suggest that phylogenomics using SCOP domains and supra-domains across sequenced genomes takes us the best part of the way towards the inference of an accurate sTOL.

Among various methods used for inferring phylogenetic trees is maximum likelihood (ML)25. In the para-infinite topological search space, ML evaluates possible trees with the likelihood of explaining the observed data, assuming that the optimal tree with the highest probability is preferred in the evolution. Although the inferred trees by ML are more accurate than those by other competing methods (such as parsimony and distance methods), ML requires an extremely expensive computation, particularly when the tree comprises thousands of genomes. To meet the high-computational demand of ML, the Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood (RAxML)26 has been developed for the inference of large trees by improving technical optimizations such as the search algorithm and parallelization. By initializing the distinct starting trees and thus avoiding being trapped in the local maxima, it is more likely to find the best trees. Moreover, RAxML allows the search for alternative tree topologies under the constraint in a manner that certain taxonomic groups (e.g., the NCBI taxonomy) are always fixed together. The NCBI taxonomy incorporates phylogenetic and taxonomic knowledge from a variety of sources into a partially-resolved common species tree27. Topologically, it is multifurcating with most nodes having many descendants and the branch length is uniform, due to a lack of quantitative information to measure divergence. Even though, the NCBI taxonomy is probably a decent starting point for the exploration of alternative tree topologies, which violate the NCBI taxonomy and which fully resolve the multifurcations. The de novo reconstruction may end in a bad tree topology if the space of possible topologies is not adequately sampled (particularly under the time constraint of a daily update). On the other hand, imposing the constraint under the NCBI taxonomy can be viewed as the input for phylogenomics to resolve the multifurcations of a taxonomic group and reduces the overall para-infinite search space to a size that is merely astronomical. Recently, RAxML has implemented a site weight calibration algorithm for weighting input characters according to their degree of agreement with a given tree (here NCBI taxonomy)28. Together, the RAxML-based integration of the known knowledge (from the NCBI taxonomy) and the hidden knowledge (from the data itself) may be practically useful in unifying our current understanding of the sTOL.

To our knowledge, there is a lack of a regularly-updated sTOL, the one that includes all publicly available sequenced genomes at any given time. Accordingly, we have developed an automated procedure of performing the RAxML-based phylogenomic analysis on molecular characters, harnessing information from the NCBI taxonomy (but not entirely constrained by it). The resulting sTOL is fully resolved and takes full advantage of both the protein structural evolutionary information in the SUPERFAMILY database and the existing taxonomic information. By comparing differences between the resulting tree and the taxonomy we are able to identify branches that, as suggested by the molecular character data, should be re-examined and possibly revised in the NCBI taxonomy. In the results we also show examples of applications, illustrating the power of using this sTOL across different biological scales. In many of them we combine the sTOL with a recently published resource29 of domain-centric ontologies; in others, through inferring ancestral domain repertoires.

Results

An automated pipeline of inferring sTOL

Central to the proposed pipeline is RAxML weight calibration-based structural phylogenomic analysis using all sequenced genomes (nearly 2,500 at the time of writing) and their protein domain compositions. The full descriptions of each step in the pipeline are detailed in the Methods. The brief summary is illustrated in Figure 1 and is described as follows. From the SUPERFAMILY database, we first obtained the assignment matrix of SCOP domains and supra-domains (hereinafter collectively referred to as ‘features’; columns) versus genomes (species; rows). Each entry in this matrix is binary, indicative of whether or not a feature exists in a genome. This genomes × features presence/absence matrix was then used as input for RAxML-based phylogenomics analysis guided by the NCBI taxonomy (top panel in Fig. 1). In order to incorporate the existing taxonomic information, we used the NCBI taxonomy twice but with different purposes: to assign/calibrate weights to features based on their congruence and to loosely constrain the topology during the search for the optimal tree (middle-right panel in Fig. 1). As a result, the sTOL incorporated not just evolutionary information from the protein structural features with congruent signals but also the existing known taxonomic information. To show the consistency/inconsistency of the NCBI taxonomy versus the molecular features, we also devised a leave-one-out test (middle-left panel in Fig. 1). The nodes (terminal tips or internal nodes) being removed from the NCBI taxonomy and then robustly recovered were considered as consistent with the input data itself. From those not recovered, we were also able to suggest several high-confident alternatives as described in next two subsections.

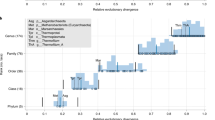

The extent of agreement between the NCBI taxonomy and the molecular data

We conducted a leave-one-out test to quantify the extent of the agreement of the NCBI taxonomy with the molecular character data (see Methods). Based on the extent to which a removed node (either a terminal tip/extant species or an internal node/taxonomic group) could be recovered and whether the alternative could be supported by the molecular data, we grouped the nodes into three categories: ‘Recovered’ with more than 80% agreement, ‘Alternative’ with strong evidence against the NCBI taxonomy and the rest ‘Others’. As such, the nodes in the NCBI taxonomy are labelled with one of the three different categories by colour-coding the edge above that node (Fig. 2). Visual inspection clearly demonstrates that the NCBI taxonomy is overwhelmingly consistent with the input data itself, irrespective of whether the removed node is an extant species or a taxonomic group. To better reveal the clade-specific quantitative information, we also looked at the relative proportions of the three different categories in major clades (the pie charts in Fig. 2). For the whole taxonomy (i.e., under the clade ‘Cellular organisms’), we found that both terminal tips and internal nodes are mostly labeled as ‘Recovered’ and terminal tips are more in agreement than internal nodes. The similar results were also observed for the three superkingdoms (Eukaryota, Bacteria and Archaea). However, the terminal tips of eukaryotes comparatively display more disagreements (21% for ‘Others’ plus 3% for ‘Alternative’) than those of the other two superkingdoms. We found that the strongest disagreement was within the animal kingdom; there is by far the highest proportion of suggested alternative taxonomic classifications, particularly among mammals. The common reason for this is low sequencing coverage of the genome and/or poor assembly leading to an incomplete proteome. In contrast, the simpler fungal genomes have the strongest agreement among eukaryote kingdoms. Figure 3 shows the parts of the NCBI taxonomy for which the molecular data suggests alternative classifications (see below for details).

The extent of agreement between the NCBI taxonomy and the molecular data.

The circular phylogram displays the NCBI taxonomy, wherein the nodes are labelled with one of three categories (‘Recovered’ in red, ‘Alternative’ in green and ‘Others’ in blue) by colour-coding the edge above that node. The pie charts illustrate the clade-specific fractions of these three categories for either terminal tips or internal nodes. The clades illustrated in the right panel (from top to bottom) include ‘Cellular organisms’, ‘Eukaryota’, ‘Archaea’ and ‘Bacteria’ and in the bottom panel (from left to right) ‘Metazoa’, ‘Fungi’ and ‘Viridiplantae’.

Detailed inspection of disagreements with the NCBI taxonomy.

The colour-coded tree is the NCBI taxonomy with alternative topologies (inserted close by in black) suggested by the molecular data. (A) Metazoa clade as exemplified by an alternative (I, in green) suggested by the molecular data, which is likely due to the biased genome assembly. (B) Viridiplantae clade containing four alternative topologies (I ~ IV, in green) suggested by the molecular data. (C) Fungal clade wherein the three internal nodes (I ~ III, in green) are strongly supported by the molecular data as being different.

A detailed inspection of disagreements with the NCBI taxonomy

Metazoa

Disagreements within the mammalian taxonomy are likely to be due to incomplete proteomes from low coverage and poorly assembled genomes, as can be seen in many cases by the lack of essential ribosomal and house-keeping genes. Outside the mammalian NCBI taxonomy, the monophyly of annelids as well as the monophyly of anthozoan cnidarians is unlikely to be wrong and in these cases the quality of genome assemblies are again likely to be the cause of the disagreement. There is some conflict amongst fishes and there is some evidence to suggest this part of the NCBI taxonomy might be questioned, such as the placement of Oryzias as a sister group to Gasterosteus (i.e., stickleback)30. However some of the species that the molecular data group together in contradiction to the NCBI taxonomy have had their genomes assembled on the genome with which they are grouped. For example, Gadus (i.e., cod) which is generally resolved as an outgroup to the tetraodontiformes and smegmamorpha, is suggested by the molecular data to group with stickleback (I in Fig. 3A). The cod genome having been assembled on the stickleback genome31 may be the reason for this, highlighting the potential for strong phylogenetic bias resulting from the annotation procedure.

Plants

Coccomyxa is an outgroup to the two Chlorella species (Chlorella vulgaris and Chlorella variabilis) in NCBI, however the molecular data recovers a clade comprising Coccomyxa and C. vulgaris (I in Fig. 3B). The C. vulgaris genome website at the JGI states that despite morphological similarities with C. variabilis it may belong to the Coccomyxa genus (no reference). The molecular data also calls into question the placement of Vitis (III in Fig. 3B), which may be uncertain32 and also the placement of Carica papaya in the brassicas (IV in Fig. 3B). The molecular data surprisingly supports a taxonomy wherein African rice (Oryza glaberrima) is more closely related to Oryza sativa japonica than Oryza sativa indica (II in Fig. 3B). In this case we can see that because the African rice genome was assembled on Oryza sativa japonica33 there is a biased overlap with Oryza sativa japonica versus Oryza sativa indica. Differences are not in genes with functions likely to be lineage-specific34, again highlighting the annotation procedure as a source of potential phylogenetic bias for whole genome studies.

Fungi

The NCBI taxonomy groups Coccidioides with Paracoccidioides but our data suggest that this clade mitosporic Onygenales is not correct. This is supported by numerous analyses35,36,37, which, as in our analysis, retrieve a clade consisting of Coccidioides, Uncinocarpus and Arthrodermataceae and another comprising Paracoccidioides and Ajellomyces (II in Fig. 3C). Arthroderma benhamae groups with Trichyophyton verrucosum in our analysis, rather than other Arthroderma species (III in Fig. 3C); other studies cast doubt on the monophyly of either genus36,38. Finally, the three species of Fusariumare recovered as monophyletic in our phylogeny (I in Fig. 3C); instead, in NCBI classification, Fusariumare oxysporum sits outside a clade comprising the other two Fusarium species and Nectria haematococca. According to the recent studies35,39, our results agree with the latest findings in the literature.

Illustrations of applications of the sTOL at different scales

Unlike the multifurcating nature of the NCBI taxonomy, the sTOL is bifurcating, only allowing exactly two descendants. However, because its reconstruction is guided under the NCBI taxonomy, it is feasible to map the internal nodes of the sTOL onto the NCBI taxonomic identifiers. As a result, the sTOL can be explicitly annotated by the taxonomy in a manner that an internal node is either mapped onto a unique taxonomic identifier or left empty (assumedly a hypothetical unknown ancestor). With this built-in taxonomic information, the sTOL is of greater use as a working reference. As illustrated here, when combined with the domain-centric Gene Ontology (dcGO) database29, the sTOL can be used to explore the distribution of a specific domain or a list of domains annotated to an ontology term. Also, the sTOL is suited for large-scale studies, exemplified by our inference of the ancestral domain repertoires during eukaryotic evolution (seen Methods). Following Dollo parsimony, which is a reasonable approximation for most molecular characters in eukaryotes23, we infer ancestral superfamily domain repertoires and their derivatives (being gained and lost compared to direct parents). In this work we focus on applications from a protein domain perspective, but the sTOL is generally applicable for providing phylogenetic contexts at any level, including that of the gene or protein.

The use for characterising the evolutionary importance of nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain

Nuclear receptors are important regulators of many key biological processes, particularly in animals and their activation requires a ligand for binding to the ligand-binding domain40. To understand the origin of ligand-dependent nuclear receptors, we looked at the superfamily domain ‘Nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain’ distributed along the well-informed branches under the eukaryotic clade of the sTOL (Fig. 4). We found this domain is absent from fungal genomes but is ubiquitous across Metazoa (including animals). At the animal-fungi boundary, it is also missing in Capsaspora owczarzaki and Choanoflagellata (i.e., Salpingoeca rosetta and Monosiga brevicollis); both are considered to be the key to understanding the last unicellular ancestor of animals41,42,43. This observation is consistent with the previous finding that nuclear receptors evolved from a ligand-activated ancestral receptor that existed near the base of the animals44. When looking at the Viridiplantae (plant) kingdom, we observed that this domain was also found in several genomes of embryophytes (land plants) but completely absent in chlorophyta (green algae). This preliminary survey implies that the origin of this nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain is much earlier than previously appreciated, calling for future studies on its evolutionary importance beyond the animal kingdom.

Presence-absence pattern of the nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain across the eukaryotic species tree of life.

The left panel illustrates the overview of the eukaryotic tree, with a branch (edge) highlighted in green if the domain can be found in all genomes under the clade attached to the branch. The right panel is the zoomed-in version of the kingdom Viridiplantae (plants), which further contains two clades, embryophytes (land plants) and chlorophyta (green algae).

The use for understanding the evolutionary history of stem cell maintenance

With the advent of cell reprogramming45,46, stem cell-related biomedical topics have become the focus of considerable research. So far, little attention has been paid to studies from an evolutionary perspective. To show the power of using the sTOL for analysing the evolution of stem cell-related function, we first selected the GO term ‘stem cell maintenance’ (GO:0019827) and retrieved all the domains (at the superfamily level) annotated with it from the dcGO database. As shown in Figure 5, these domains involved in stem cell maintenance experience a steady increase in number along the path from Eukaryota to the Fungi/Metazoa group. Thereafter, two different trends are observed. A continued increase is seen in the metazoan path leading to Homo sapiens, whereas a gradual loss occurs in the fungal path leading to Yeast. When it comes to the Viridiplantae path from Eukaryota to Arabidopsis, similar changes are observed as in the fungal path. Although the exact implication remains unclear, this difference between the animal kingdom and the other two clearly imply that more varied domains involved in stem cell maintenance were needed during animal evolution. We also observed no changes from mammals to human, displaying a high degree of conservation.

A list of domains annotated by stem cell maintenance and their distribution over the three kingdoms in eukaryotic evolution.

The diagram in the top panel shows the paths covering three kingdoms. The bottom panel lists the details of their presence (1) and absence (0) patterns at the major branching points of eukaryotic evolution. The last row tells how many distinct domains (i.e., superfamilies) are related to stem cell maintenance.

The use for studying the evolution of enzymes, post-translational modifications, metabolism, diseases and phenotypes

Here, we further demonstrate that the sTOL can provide the evolutionary context for studying a list of related domains that either share the same enzyme annotation, or harbour the same post-translational modification, or are involved in the same pathway (see Supplementary Fig. S1). The ‘Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase’ from Enzyme Commission47 is seen to increase in the number of domains along the metazoan path, decreasing in the fungal path and remaining constant for the Viridiplantae path. The post-translational modification ‘Oxidation’ from UniProtKB KeyWord48 experiences no change from Eukaryota to the Fungi/Metazoa group. Interestingly, thereafter we observe the decrease to Metazoa and no change to Fungi. We also observe no change for the ‘Hormone metabolism’ UniPathway49 for the metazoan path leading to Homo sapiens and a slight decrease for the other two kingdoms. In addition to these mechanistic activities, the sTOL also allows for the evolutionary studies of diseases and phenotypes (see Supplementary Fig. S2). From the Fungi/Metazoa group to the Metazoa, there is an increase in the number of domains annotated by the ‘Proto-oncogene’ term but a decrease in those annotated by the ‘Oncogene’ term. The domains annotated by ‘Embryonic lethality’ by mammalian phenotype term50 are stable for all three kingdoms. In summary, the sTOL integrated with the dcGO ontology infrastructure helps to generate many new evolutionary questions awaiting further exploration.

The use for getting functional insights into eukaryotic evolution

The sTOL is particularly promising for large-scale studies, including those aiming to shed functional insights into eukaryotic evolution beyond mere narrative descriptions. This value is complemented by ancestral state reconstruction within the sTOL (see Methods). Using ‘dcGO Enrichment’51, we perform enrichment analysis to infer which GO terms are over-represented. These functional comparisons of those gained/lost/present in ancestral domain repertoires not only give a view of ancestral genomes, but also provide a rational explanation for the observed domain gains and losses. As shown in Table 1, most domains seen in eukaryotic ancestors are conferred with catalytic activity and are involved in metabolic processes, consistent with the functional importance of these basic processes in the rise of Eukaryota. Furthermore, domains gained in Metazoa outnumber domains lost, but the opposite trend is observed in Fungi. The domain gains during animal evolution are predominantly associated with developmental processes, regulation, signalling and the extracellular matrix (Table 1). On the other hand, the domain losses during fungal evolution are enriched with the signalling activities and the extracellular matrix (Table 1). Complex functions gained in the rise of animals and lost in the rise of Fungi from their common ancestor are likely to explain the observed differences in phenotypic complexity. It is consistent with the recent report on strong functional patterns observed during eukaryotic evolution52.

Discussion

We report a resource called ‘sTOL’, the reference tree of sequenced life. It is the product of an automated pipeline using existing status quo taxonomic information in concert with structural domain information from all sequenced genomes that are publicly available. We quantify the reliability of using the NCBI taxonomy as a partial constraint tree; the NCBI taxonomy is used as a way of representing electronically the status quo referred to above. In doing so we observe that there are potentially significant improvements that can be made to the NCBI taxonomic classification, particularly in the fungi kingdom; we also see that the current state of many, particularly animal, genome assemblies is inadequate. We show that by further resolving the highly multifurcating NCBI taxonomy into a binary tree, we can produce a high-quality fully-resolved reference tree. The species included in sTOL represents a small percentage of those believed to exist (only ~2,500 among an estimate of ~9 million species53). As the quality, coverage, assembly and diversity of genomes being sequenced improves, the tree of life reconstructed using this pipeline will become increasingly more accurate, even without taking into account our continuing development and improvement of the method. We find that the fungal kingdom forms the highest quality part of the tree, with the greatest agreement between the NCBI taxonomy and our molecular data. In contrast, the poor state of many animal genomes indicates that a greater quality and number of genomes are required for this part of the tree. Another obstacle for building a tree of life is the presence of horizontal gene transfer (HGT), particularly in bacteria. To mitigate the impact of HGT, we utilise molecular characters in the form of SCOP structural superfamilies, families, supra-domains and full-length domain architectures. These are more tolerant to homoplasy (less HGT-sensitive) than their residual genes/proteins23,24.

The sTOL reference tree enables the inclusion of phylogenetic context to biological studies of completely sequenced genomes. We have presented examples to illustrate the value of the sTOL both in challenging the status quo and to generate new hypotheses. In addition to the cases shown in the Results section, the complete data and infrastructure can be browsed or downloaded at http://supfam.org/SUPERFAMILY/cgi-bin/dctree.cgi. To allow navigation of the sTOL, we display in text form the lineage above leading from the node currently being displayed to its ancestors and below to its two most direct children. This tree contains many internal nodes that do not exist in the NCBI taxonomy, so these are labelled as ‘inferred ancestor’ and highlighted in gray. TreeVector54 can be used for visualizing (on a separate page) the tree structure in a more graphical yet still interactive manner. On the main (text-form) pages, we also indicate where domains are gained/lost/present along the lineages. Newick format is also provided for download of the tree as a whole or for any sub-part. What elevates the sTOL from a reference tree into a potentially powerful tool, is the ability to link together three different bits of information (i.e., taxonomic information, protein domains and domain-centric functional annotations) in a single analysis. The domain annotation is provided by the SUPERFFAMILY database and numerous functional and phenotypic ontologies are provided by the dcGO database. The current release and forthcoming extensions will open doors for the sTOL not only as a comprehensive reference species tree, but as a resource to connect evolution, function and phenotype. We anticipate that this resource together with its tools, freely available and open to the scientific community, will be of great value in making sense of the increasing mass of genomic data, in particular for (the rapidly growing number of) those who need a phylogenetic context within which to interpret their sequence data.

Methods

Genomic domain assignment sources in the SUPERFAMILY database

We have compiled SCOP domain assignments over all completely sequenced genomes that are currently available (stored in the SUPERFAMILY database18). New genomes are routinely added and are automatically annotated with domain assignments using HMMs19. The main results presented here are on a frozen data set, which at the time the work began consisted of 1,731 genomes/species (comprising 1,282 bacteria, 105 archaea and 344 eukaryotes). The taxonomy used in this work was the subset of nodes and branches extracted from the full NCBI taxonomy relevant to those species for which completely sequenced genomes are available (those in our set). The protein sequences in these genomes were assigned to 1,919 distinct superfamilies and 3,815 distinct families from SCOP (version 1.75). In addition to the presence/absence domain occurrence information, SUPERFAMILY also provides an algorithm for unambiguously converting a protein sequence into ‘domain architecture’, a sequential order of SCOP superfamilies or gaps.

In multi-domain proteins, certain domains are frequently observed in combination with each other in different contexts. Following on from our previous work22, we defined combinations of two or more successive domains as supra-domains that could be found in at least two different domain architectures. Unlike the domain architectures (which may have N or C-terminals with no assigned domain), in this study supra-domains must begin and end with a known domain. Genomic information of domains and supra-domains was used to create a genomes × features matrix. Each cell in this matrix is ‘1’ if a feature (an individual domain or a supra-domain or a full-length domain architecture in a column) can be found in a genome (in a row) and ‘0’ otherwise. Since we are only interested in the contribution of a distinct feature, redundant features with identical across-genome patterns are excluded from considerations. In total, there remains a presence/absence matrix of 1,731 genomes × 89,617 features for the subsequent analysis. The copy number of features was not used because this varies wildly depending on the gene prediction strategy used by the genome projects.

Phylogenomic analysis by RAxML

The maximum likelihood phylogenomic analysis of our large matrix was conducted using the Pthreads-SSE3-vectorized version of RAxML version 7.2.826. RAxML allows for the ML search on binary datasets other than DNA and protein characters. Using the genomes-to-features matrix as input data, we performed an inference under the general GTR gamma model of rate heterogeneity. To keep the ML topological search following the NCBI taxonomy, we used the RAxML option (-g) by specifying a multifurcating constraint tree. The RAxML-based calibration algorithm28 for weighting features using NCBI taxonomy consists of four major steps:

-

1

Using input data and the NCBI taxonomy tree to initially infer a binary and taxonomy-constrained tree topology as a starting tree;

-

2

Using input data and the previous resulting tree (via ‘-t’ option) to infer the integer weights for features (via ‘-f u’ option), up-weighting the congruent ones while down-weighting those incongruent;

-

3

Using input data and the previous resulting weight vector to infer the binary and taxonomy-constrained best tree as a final tree topology.

-

4

Using input data (restricted to full-length domain architectures) and the previous final tree topology (via ‘-t’ option) to estimate the branch length.

Identifying disagreements with the NCBI taxonomy tree using a leave-one-out test

We devised a leave-one-out test to identify which information in the NCBI taxonomy should not be used to constrain the tree. Specifically, we generated many different constraint tree topologies by removing nodes (either a terminal tip/extant species or an internal node/taxonomic group) from the taxonomy. This new topology (instead of the whole taxonomy) was then used to constrain the best tree search when executing RAxML. In other words, it allowed for this removal node to be freely placed during the tree topology optimization. There are a total of 2,464 tests involving 1,731 tips and 734 internal nodes (except for the root), each independently repeated about 60 times. All these tests were run using the Canadian HPC Mammouth parallel 2 (https://rqchp.ca/?mod=cms&pageId=1388&lang=EN&navrev=off&version=-1&). More than 300,000 trees were built and each cost computational time of roughly 1 hour (24 cores, 32GB of RAM), totaling more than 8 millions CPU-hours.

We measured whether or not the removed nodes could get recovered using the molecular character data alone. If the node is recovered in more than 80% of the repetitions of the tree building, we labeled this node in the NCBI taxonomy as ‘Recovered’ with the input data itself. The remainder were further split into two categories based on the strict criteria: 1) whether the alternative (i.e., the best-scoring ML tree among the repeats) in the alternative placement achieved better ML value than that of the original (i.e., the best-scoring ML tree without the removal from almost 3,000 runs); and 2) whether the alternative placement achieved a good bootstrap support value (90 at least). If both criteria were met then the node was labeled as ‘Alternative’; otherwise, it was labeled ‘Others’.

Inferring ancestral superfamily domain repertoires in Eukaryotes by Dollo parsimony

Phyletic patterns of domains in extant genomes are the cumulative result of evolutionary domain events including vertical inheritance (by default), loss and gain. Domains can also be gained via de novo creation (which can only happen once per superfamily by definition) or horizontal transfer or other convergent evolutionary events, which is unlikely particularly in eukaryotes23. Dollo parsimony assumes domain gain occurring once and only once and seeks an explanation that requires minimal evolutionary changes (i.e., minimal domain losses). Focusing on extant species within the Eukaryotic clade of the working phylogeny, we apply Dollo parsimony to infer ancestral superfamily/family domain and architecture repertoires at all branching points in eukaryotic evolution (not in the other two superkingdoms due to convergent evolutionary events). This allows us to reconstruct ancestral domain repertoires that were present at these points and to list which molecular characters were gained and lost relative to their parents.

Inferring enriched GO terms by domain-based enrichment analysis

Previously, we developed a novel methodology18 to generate the dcGO database29, which includes but is not limited to domain-centric GO annotations (and the slim version of the ontology). GO terms in this slim version are divided into four levels of increasing granularity which we class as: highly general, general, specific and highly specific. Based on these GO terms and their annotations, we also developed ‘dcGO Enrichment’51 to perform enrichment analysis for gained/lost/present ancestral domain repertoires at the superfamily level. Enrichment analysis was based on the hypergeometric distribution and the statistical significance of GO term enrichments was assessed via the Benjamini-Hochberg derived step-up procedure for false discovery rate (FDR)55.

Data access

The sTOL server is available at http://supfam.org/SUPERFAMILY/sTOL, as a natural extension to the SUPERFAMILY database and compliment to the dcGO database.

References

Mardis, E. R. A decade's perspective on DNA sequencing technology. Nature 470, 198–203 (2011).

Metzker, M. L. Sequencing technologies - the next generation. Nat Rev Genet 11, 31–46 (2010).

Eisen, J. A. & Fraser, C. M. Phylogenomics: intersection of evolution and genomics. Science 300, 1706–1707 (2003).

Snel, B., Bork, P. & Huynen, M. A. Genome phylogeny based on gene content. Nat Genet 21, 108–110 (1999).

Tekaia, F., Lazcano, A. & Dujon, B. The genomic tree as revealed from whole proteome comparisons. Genome Res 9, 550–557 (1999).

Deeds, E. J., Hennessey, H. & Shakhnovich, E. I. Prokaryotic phylogenies inferred from protein structural domains. Genome Res 15, 393–402 (2005).

Yang, S., Doolittle, R. F. & Bourne, P. E. Phylogeny determined by protein domain content. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 373–378 (2005).

Wang, M. & Caetano-Anolles, G. Global phylogeny determined by the combination of protein domains in proteomes. Mol Biol Evol 23, 2444–2454 (2006).

Fukami-Kobayashi, K., Minezaki, Y., Tateno, Y. & Nishikawa, K. A tree of life based on protein domain organizations. Mol Biol Evol 24, 1181–1189 (2007).

Rokas, A., Williams, B. L., King, N. & Carroll, S. B. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature 425, 798–804 (2003).

Venditti, C., Meade, A. & Pagel, M. Detecting the node-density artifact in phylogeny reconstruction. Syst Biol 55, 637–643 (2006).

Valas, R. E., Yang, S. & Bourne, P. E. Nothing about protein structure classification makes sense except in the light of evolution. Curr Opin Struct Biol 19, 329–334 (2009).

Karplus, K., Barrett, C. & Hughey, R. Hidden Markov models for detecting remote protein homologies. Bioinformatics 14, 846–856 (1998).

Andreeva, A. et al. Data growth and its impact on the SCOP database: new developments. Nucleic Acids Res 36, D419–425 (2008).

Pethica, R. B., Levitt, M. & Gough, J. Evolutionarily consistent families in SCOP: sequence, structure and function. BMC Struct Biol 12, 27 (2012).

Rose, P. W. et al. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: redesigned web site and web services. Nucleic Acids Res 39, D392–401 (2011).

Chothia, C. & Gough, J. Genomic and structural aspects of protein evolution. Biochem J 419, 15–28 (2009).

de Lima Morais, D. A. et al. SUPERFAMILY 1.75 including a domain-centric gene ontology method. Nucleic Acids Res 39, D427–434 (2011).

Gough, J., Karplus, K., Hughey, R. & Chothia, C. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of hidden Markov models that represent all proteins of known structure. J Mol Biol 313, 903–919 (2001).

Gough, J. Genomic scale sub-family assignment of protein domains. Nucleic Acids Res 34, 3625–3633 (2006).

Wilson, D. et al. The SUPERFAMILY database in 2007: families and functions. Nucleic Acids Res 35, D308–313 (2007).

Vogel, C. et al. Supra-domains: evolutionary units larger than single protein domains. J Mol Biol 336, 809–823 (2004).

Gough, J. Convergent evolution of domain architectures (is rare). Bioinformatics 21, 1464–1471 (2005).

Yang, S. & Bourne, P. E. The evolutionary history of protein domains viewed by species phylogeny. PLoS One 4, e8378 (2009).

Delsuc, F., Brinkmann, H. & Philippe, H. Phylogenomics and the reconstruction of the tree of life. Nat Rev Genet 6, 361–375 (2005).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006).

Federhen, S. The NCBI Taxonomy database. Nucleic Acids Res 40, D136–143 (2012).

Berger, S. A., Stamatakis, A. & Lücking, R. Morphology-based phylogenetic binning of the lichen genera Graphis and Allographa (Ascomycota: Graphidaceae) using molecular site weight calibration. Taxon 60, 1450–1457 (2011).

Fang, H. & Gough, J. dcGO: database of domain-centric ontologies on functions, phenotypes, diseases and more. Nucleic Acids Res 41, D536–D544 (2013).

Negrisolo, E. et al. Different phylogenomic approaches to resolve the evolutionary relationships among model fish species. Mol Biol Evol 27, 2757–2774 (2010).

Star, B. et al. The genome sequence of Atlantic cod reveals a unique immune system. Nature 477, 207–210 (2011).

Burleigh, J. G. et al. Genome-scale phylogenetics: inferring the plant tree of life from 18,896 gene trees. Syst Biol 60, 117–125 (2011).

Sakai, H. et al. Distinct evolutionary patterns of Oryza glaberrima deciphered by genome sequencing and comparative analysis. Plant J. 66, 796–805 (2011).

Lespinet, O., Wolf, Y. I., Koonin, E. V. & Aravind, L. The role of lineage-specific gene family expansion in the evolution of eukaryotes. Genome Res 12, 1048–1059 (2002).

Morgenstern, I. et al. A molecular phylogeny of thermophilic fungi. Fungal Biology 116, 489–502 (2012).

Untereiner, W. A. et al. The Ajellomycetaceae, a new family of vertebrate-associated Onygenales. Mycologia 96, 812–821 (2004).

Burmester, A. et al. Comparative and functional genomics provide insights into the pathogenicity of dermatophytic fungi. Genome Biol 12, 16 (2011).

Sugiyama, M., Ohara, A. & Mikawa, T. Molecular phylogeny of onygenalean fungi based on small subunit ribosomal DNA (SSU rDNA) sequences. Mycoscience 40, 251–258 (1999).

Wang, M. & Caetano-Anolles, G. The evolutionary mechanics of domain organization in proteomes and the rise of modularity in the protein world. Structure 17, 66–78 (2009).

Gronemeyer, H., Gustafsson, J. A. & Laudet, V. Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nat Rev Drug Discov 3, 950–964 (2004).

Michod, R. E. Evolution of individuality during the transition from unicellular to multicellular life. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 Suppl 1, 8613–8618 (2007).

Sebe-Pedros, A. et al. Unexpected repertoire of metazoan transcription factors in the unicellular holozoan Capsaspora owczarzaki. Mol Biol Evol 28, 1241–1254 (2011).

King, N. et al. The genome of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis and the origin of metazoans. Nature 451, 783–788 (2008).

Bridgham, J. T. et al. Protein evolution by molecular tinkering: diversification of the nuclear receptor superfamily from a ligand-dependent ancestor. PLoS Biol 8 (2010).

Takahashi, K. et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872 (2007).

Yu, J. et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920 (2007).

Fleischmann, A. et al. IntEnz, the integrated relational enzyme database. Nucleic Acids Res 32, D434–437 (2004).

Bairoch, A. et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res 33, D154–159 (2005).

Morgat, A. et al. UniPathway: a resource for the exploration and annotation of metabolic pathways. Nucleic Acids Res 40, D761–769 (2012).

Smith, C. L. & Eppig, J. T. The Mammalian Phenotype Ontology: enabling robust annotation and comparative analysis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 1, 390–399 (2009).

Fang, H. & Gough, J. A domain-centric solution to functional genomics via dcGO Predictor. BMC Bioinformatics 14, S9 (2013).

Zmasek, C. M. & Godzik, A. Strong functional patterns in the evolution of eukaryotic genomes revealed by the reconstruction of ancestral protein domain repertoires. Genome Biol 12, R4 (2011).

Mora, C. et al. How many species are there on Earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol 9, e1001127 (2011).

Pethica, R., Barker, G., Kovacs, T. & Gough, J. TreeVector: scalable, interactive, phylogenetic trees for the web. PLoS One 5, e8934 (2010).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological 57, 289–300 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We thank Compute Canada site, Mammoth, for access to supercomputing resources. Compute Canada is supported by the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI). This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [BB/G022771/1 to J.G.].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G. conceived and designed the work; D.M. and J.G. compiled genome data; H.F., M.O., R.P., A.S., O.R. and J.G. analysed data; Phil Donoghue involved in initial design; A. Stamatakis contributed to RAxML analysis; H.F., J. Greenwood and J.G. interpreted results; H.F. and J.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary info

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, H., Oates, M., Pethica, R. et al. A daily-updated tree of (sequenced) life as a reference for genome research. Sci Rep 3, 2015 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02015

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02015

This article is cited by

-

A proteome view of structural, functional, and taxonomic characteristics of major protein domain clusters

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Actively Tunable Fano Resonance Based on a T-Shaped Graphene Nanodimer

Plasmonics (2016)

-

MDAT- Aligning multiple domain arrangements

BMC Bioinformatics (2015)

-

Nanostructured silicon success

Nature Photonics (2015)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.