Abstract

We propose a hybrid nano-structuring scheme for tailoring thermal and thermoelectric transport properties of graphene nanoribbons. Geometrical structuring and isotope cluster engineering are the elements that constitute the proposed scheme. Using first-principles based force constants and Hamiltonians, we show that the thermal conductance of graphene nanoribbons can be reduced by 98.8% at room temperature and the thermoelectric figure of merit, ZT, can be as high as 3.25 at T = 800 K. The proposed scheme relies on a recently developed bottom-up fabrication method, which is proven to be feasible for synthesizing graphene nanoribbons with an atomic precision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the fact that it has been more than 150 years since the discovery of thermoelectric (TE) effect, its applications are still limited1. This limitation stems from the apparently incompatible demands for high TE efficiency which is related to the material specific dimensionless figure of merit defined as ZT = S2GT/κ with S being the Seebeck coefficient, G being the electrical conductance, T being temperature and κ = κel + κph is the thermal conductance consisting of electron and phonon contributions. A good TE material needs to have a high electrical conductivity like in a metal, a high Seebeck coefficient like in an insulator and a low thermal conductivity like in a glass2. Meeting these diverse, if not contradictory, attributes in a single system is an extremely difficult challenge. Nano-scale fabrication techniques, on the other hand, enable the tailoring of the material properties to a previously unprecedented extend. By reducing the cross section of a nanowire, its TE performance can be enhanced significantly due to the confinement of electrons3. Nano-structuring also offers ways to control phonon transport by tuning phonon dispersions and introducing scatterers specially designed to scatter the dominant phonon wavelengths, thus enhance ZT4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Considering the fact that low frequency acoustic phonons dominate phonon conduction, the size of the phonon scatterers plays an important role in lowering thermal conductivity17,18,19,20. It is worth mentioning that the knowledge of ballistic transport properties is a necessary starting point for investigating TE efficiency21,22. On the other hand, addressing the scattering mechanisms is not only required for an accurate prediction, but engineering of scatterers is a promising way to enhance the TE performance23. Indeed, state-of-the-art TE materials design relies on engineering of scattering mechanisms for heat and charge carriers so as to approach the phonon glass-electron crystal limit24.

Graphene possesses a wide range of superlative material properties25, including the record value for thermal conductivity26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. Still, it is possible to tailor the thermal transport properties of graphene and graphene nanoribbons' (GNRs) by nano-structuring techniques such as edge roughness11,13, defect engineering13,38, isotope engineering20,39 and introducing periodic nano-holes40. Bottom-up fabrication of GNRs using surface-assisted coupling of molecular precursors is not only a promising technique to obtain atomically precise GNRs with predefined geometries and sub-nanometer widths41, but it also enables a hybrid scheme for TE efficiency by combining geometrical structuring with isotope clustering. This combination enables a reduction of the thermal conductivity by up to two orders of magnitude. Also, electronic mini-bands are formed due to the chevron geometry, approaching the Mahan-Sofo condition42. The electronic bandwidths are compatible with the optimal values defined by Zhou et al23. As a result, the Seebeck coefficient and the power factor are substantially enhanced and thus ZT values up to 3.25 are possible.

We consider two types of GNRs which have been synthesized by Cai et al41. The first type has an armchair edge shape with 7 dimers per unit cell and a straight geometry, s-GNR, that was obtained from 10,10′-dibromo-9-9′-bianthryl precursor monomers. The second GNR type is obtained from tetraphenyl-triphenylene monomers and has a chevron-type geometry, c-GNR. Both GNRs have well-defined geometries and their edges are passivated with hydrogen. (see Figure 1a) The width of a ribbon, w, is defined as the total area of hexagons in its unit cell, divided by the unit cell length (w = 0.62 nm and 0.93 nm for s-GNR and c-GNR, respectively) and we use the interlayer distance of graphite as the ribbon height. We employ the density functional tight binding (DFTB) approach to calculate the electronic and vibrational properties of the GNRs43. Having obtained the force constant matrices and the electronic Hamiltonians from DFTB simulations, we use atomistic Green's functions (AGF)44 and nonequilibrium Green's functions (NEGF)45 for calculating the phonon and electron transport properties, respectively. (see Supplementary Information for details)

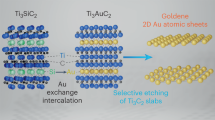

Structural aspects, isotope distribution types and ballistic transmission spectra of bottom-up fabricated graphene nanoribbons (GNRs).

(a) Structures of precursors and corresponding straight and chevron type graphene nanoribbons, s-GNR and c-GNR. (b) Heavy isotopes can be distributed at the atomic or precursor level. Grey, 12C; black, 14C; white H. Ballistic phonon (c) and electron (d) transmission spectra are plotted for both GNR types, where mini band formation due to the geometry of c-GNR is evident.

Results

Ballistic phonon and electron transmission spectra of s-GNR and c-GNR are plotted in Figures 1c and 1d, respectively. The first observation is that the phonon dispersions of the s-GNR and c-GNR are significantly different due to their geometries. The chevron shape gives rise to the formation of mini-bands with small group velocities and numerous phonon energy gaps arise (see Figure 1c and the Supplementary Information). Acoustic phonons, which have large dispersions and very long mean free paths in straight GNRs, have significantly smaller group velocities in c-GNRs. As a result, ballistic phonon transmission is significantly altered (Figure 1c) and ballistic lattice thermal conductance per cross section area, κph/A, is reduced by 69% at room temperature (see Figure 2 and Table I). More importantly, the phonon density of states (DOS) of c-GNR posseses many van Hove singularities in the entire spectrum giving rise to enhanced scattering rates upon the inclusion of scatterers.

Phonon transport through isotopically disordered GNRs.

Thermal conductance per cross section area (κ/A) are plotted as functions of temperature in (a) and ribbon length (L) in (b), for s-GNR (blue) and c-GNR (red). Thermal conductance is minimum for maximal disorder (d = 50%) for a given distribution type. Precursor distribution always yields lower κ/A for a given isotope density for s-GNR. For c-GNR, precursor distribution yields larger κ/A at low density and short L. For long systems, even a low density of heavy precursors give rise to stronger suppression of phonon transport than that of atomic distribution of isotopes. Solid lines in (b) depict κ/A in the absence of 14C isotopes.

We introduce 14C isotopes in order to suppress phonon transport without damaging the electronic quality with (i) random atomic distribution of isotopes and (ii) random distribution of heavy precursors (Firgure 1b). In the first case, each 14C atom is a scattering center, while in the second case the precursors consist of only 12C or only 14C. Clusters of impurities are introduced in order to overcome the alloy limit. This is due to the fact that scattering rates increase with the size of the scatterer for long wavelength phonons, which dominate lattice thermal conduction. For both s-GNR and c-GNR, we consider both atomic and precursor distributions with 14C densities being d = 10% and 50%.

First, we analyze the effects of different isotope distributions on the phonon transport properties of the straight s-GNR (Figure 2a–b). Using the AGF technique, we calculate transmission spectra at various lengths for ensembles consisting of at least 25 samples. The phonon mean-free-paths (MFPs) are obtained using  . Here, L is the ribbon length,

. Here, L is the ribbon length,  stands for ensemble averaged transmission value,

stands for ensemble averaged transmission value,  is the ballistic transmission. For the sake of comparison, we also estimate the phonon MFPs from transmission spectra of individual scatterers, by making use of scaling theory as

is the ballistic transmission. For the sake of comparison, we also estimate the phonon MFPs from transmission spectra of individual scatterers, by making use of scaling theory as

Here, Nuc is the number of atoms in the unit cell, luc is the length of the unit cell with i being the atomic index and  is the transmission spectrum of GNR when only the ith atom is isotopically different in the entire system. The scaling approximation works well when d is small so that interference between different scattering events can be neglected.

is the transmission spectrum of GNR when only the ith atom is isotopically different in the entire system. The scaling approximation works well when d is small so that interference between different scattering events can be neglected.  agrees well with

agrees well with  for d ≤ 10%. For d > 10%, scaling theory often predicts longer mean-free-paths (MFPs), because it disregards multiple scattering effects. That is, the relation

for d ≤ 10%. For d > 10%, scaling theory often predicts longer mean-free-paths (MFPs), because it disregards multiple scattering effects. That is, the relation  ∝ 1/d does not hold for d > 10%. Comparing the values of

∝ 1/d does not hold for d > 10%. Comparing the values of  for different isotope densities, it is found that d = 10% always yields longer

for different isotope densities, it is found that d = 10% always yields longer  than d = 50%, when the distribution type (atomic or precursor is kept the same), which is also predicted from Equation 1. On the other hand, different distribution types, when d is kept constant, give rise to opposite behavior at low and high frequency regions of the spectrum. At low frequency, the atomic distribution generally yields longer

than d = 50%, when the distribution type (atomic or precursor is kept the same), which is also predicted from Equation 1. On the other hand, different distribution types, when d is kept constant, give rise to opposite behavior at low and high frequency regions of the spectrum. At low frequency, the atomic distribution generally yields longer  than the precursor distribution, while the opposite holds at high frequencies19,20. (see Supplementary Information) In the Rayleigh limit, the scattering cross section increases with

than the precursor distribution, while the opposite holds at high frequencies19,20. (see Supplementary Information) In the Rayleigh limit, the scattering cross section increases with  , where Ns is the number of atoms in the scattering center. At high frequencies, on the other hand, the scattering cross section scales as

, where Ns is the number of atoms in the scattering center. At high frequencies, on the other hand, the scattering cross section scales as  46. One route to suppress lattice thermal conduction is the so called nanoparticle-in-alloy approach, which incorporates clusters of scatterers together with alloying and aims to shorten mean-free-paths in the entire phonon spectrum17. In our approach, effective suppression of high-frequency phonons is realized by combining the effects of geometrical structuring, i.e chevron geometry with clustered isotopes. Similar to s-GNR, low frequency phonons in c-GNR are scattered more effectively by precursor distribution of isotopes while atomic scatterers suppress high energy phonons more strongly (see Supplementary Information). Combined with the effect of geometry on phonon dispersions,

46. One route to suppress lattice thermal conduction is the so called nanoparticle-in-alloy approach, which incorporates clusters of scatterers together with alloying and aims to shorten mean-free-paths in the entire phonon spectrum17. In our approach, effective suppression of high-frequency phonons is realized by combining the effects of geometrical structuring, i.e chevron geometry with clustered isotopes. Similar to s-GNR, low frequency phonons in c-GNR are scattered more effectively by precursor distribution of isotopes while atomic scatterers suppress high energy phonons more strongly (see Supplementary Information). Combined with the effect of geometry on phonon dispersions,  is always shorter than 100 nm for ω > 50 cm−1 at 50% isotope density with precursor distribution and when the c-GNR is longer than 1 μm these phonons have negligibly small contribution to heat transport.

is always shorter than 100 nm for ω > 50 cm−1 at 50% isotope density with precursor distribution and when the c-GNR is longer than 1 μm these phonons have negligibly small contribution to heat transport.

Phonon thermal conductance is calculated from the ensemble averaged transmission values as

where fB is the Bose-Einstein distribution function. In Figure 2, the phonon thermal conductance per cross section area (κph/A) is plotted as a function of temperature and GNR length (L), for pristine and isotopically engineered GNRs having atomic and precursor isotope distributions with d = 10% and 50% for s-GNR (blue) and c-GNR (red). For s-GNR, d = 50% always yields lower κph than d = 10% for both distribution types and atomic distribution gives rise to higher κph. For c-GNR, on the other hand, the atomic distribution of isotopes yields higher κph for L > 0.08 μm independent of d and higher d results in lower κph for a given distribution type. The room temperature behavior of κph for c-GNRs with a precursor distribution at different L with d = 10% is a consequence of the frequency and length dependence of phonon transmission on distribution type (Figure 2b). κph is highest with dprec = 10% at L < 0.01 μm, where datom = 10% yields the highest κph for L > 0.02 μm. For L > 0.08 μm, dprec = 10% results in κph lower than datom = 50%. This is because (i) at short L, phonons with ω > 50 cm−1 have appreciable contribution to κph and they have longer  for precursor distribution; (ii) for long L, phonons with ω > 50 cm−1 are strongly suppressed independent of the distribution type for both d (i.e. only low frequency phonons contribute to κph) and

for precursor distribution; (ii) for long L, phonons with ω > 50 cm−1 are strongly suppressed independent of the distribution type for both d (i.e. only low frequency phonons contribute to κph) and  is shorter for precursor distribution of isotopes. As a result, the precursor distribution of isotopes is highly efficient in reducing the thermal conductivity of c-GNR.

is shorter for precursor distribution of isotopes. As a result, the precursor distribution of isotopes is highly efficient in reducing the thermal conductivity of c-GNR.

Comparing the area normalized phonon thermal conductance values in Table I, we find that the ballistic value of κph/A is reduced by 69% due to chevron geometry. Isotopic disorder induces suppressions of 97% (89%) and 98.8% (91%) for c-GNR (s-GNR) with precursor and atomic distributions, respectively. In other words, compared to the atomic distribution, κ/A is reduced by 54% (18%) for the precursor distribution in c-GNRs (s-GNRs). As a comparison, thermal conductivity of isotopically disordered two-dimensional graphene is lower than the isotopically pure sample by about a factor of 2 and in GNRs reductions by a factor of 3 with respect to the pure case were reported39,47.

The geometrical aspects of GNRs are not only crucial for the suppression of phonon transport, but they also enable electronic band engineering for tailoring the TE efficiency. The formation of mini-bands in c-GNR narrows the dispersion of electrons participating in transport. It was shown by Mahan and Sofo that, if one disregards scatterings, a Diracdelta shaped resonance in the electronic DOS close to the Fermi energy constitutes the optimal electronic structure for TE performance42. That is, the sharper the resonance, the better the TE performance that can be. In c-GNR, the band widths range between 0.1 to 0.2 eV and an extremely high TE efficiency is predicted within the ballistic electron assumption (see Supplementary Information). On the other hand, for a realistic calculation it is necessary to address the scattering effects in the electronic transport as well. In this case, TE performance is largely determined by the dimensionality of the system23. Anderson disorder48, for example, resembles the scattering model where the relaxation time is inversely proportional to the DOS and it was previously utilized by White et al. to explore the electron transport length-scales in carbon nanotubes49. In the simplest case of a quasi-one-dimensional wire with a single band having dispersion E(k) = –W/2 cos(ka), the electronic MFP is  (E) = aW2/4σ2(1–(2E/W)2), where W is the band with, a is the unit cell length and σ is the standard deviation of onsite disorder. As pointed out by Zhou et al.23, when W approaches zero, the mean free path and the transmission vanish and ZT becomes zero. Therefore W > 2.4 kBT is required for optimum TE performance23.

(E) = aW2/4σ2(1–(2E/W)2), where W is the band with, a is the unit cell length and σ is the standard deviation of onsite disorder. As pointed out by Zhou et al.23, when W approaches zero, the mean free path and the transmission vanish and ZT becomes zero. Therefore W > 2.4 kBT is required for optimum TE performance23.

Returning to the c-GNR, we perform NEGF transport calculations with Anderson disorder (details explained in the Supplementary Information). The random onsite energies are chosen from an energy range whose width, wA, is set to be proportional to the temperature as  . Having calculated the transmission spectra

. Having calculated the transmission spectra  for each sample, we average over an ensemble of 25 samples to get

for each sample, we average over an ensemble of 25 samples to get  and obtain the TE coefficients as a function of temperature (T), chemical potential (μ) and sample length (L) (see Supplementary Information). The maxima of electric conductance, G, is reduced at elevated temperatures due to enhanced electron scattering, which reduces the Seebeck coefficient, S, as well. On the other hand, the peak values in the power factor (P = S2G) close to the edges of the valence and conduction bands are not affected by temperature significantly. This is mainly due to the enhanced values of G with T, when μ is inside the band gap. This effect is specific to the valence and conduction bands, while P is suppressed at elevated temperatures for the rest of the bands. Around the charge neutrality point κ is dominated by κph, which is suppressed by scattering from isotopic precursors. Despite the fact that ZTmax is considerably reduced compared to the ballistic electron assumption, where ZT can be as high as 7 for long GNRs, ZT ≥ 2 is achieved at room temperature for 1 μm > L > 0.1 μm. Higher ZT is possible at higher temperatures for shorter c-GNRs, e.g. ZT = 3.25 is predicted at T = 800 K and

and obtain the TE coefficients as a function of temperature (T), chemical potential (μ) and sample length (L) (see Supplementary Information). The maxima of electric conductance, G, is reduced at elevated temperatures due to enhanced electron scattering, which reduces the Seebeck coefficient, S, as well. On the other hand, the peak values in the power factor (P = S2G) close to the edges of the valence and conduction bands are not affected by temperature significantly. This is mainly due to the enhanced values of G with T, when μ is inside the band gap. This effect is specific to the valence and conduction bands, while P is suppressed at elevated temperatures for the rest of the bands. Around the charge neutrality point κ is dominated by κph, which is suppressed by scattering from isotopic precursors. Despite the fact that ZTmax is considerably reduced compared to the ballistic electron assumption, where ZT can be as high as 7 for long GNRs, ZT ≥ 2 is achieved at room temperature for 1 μm > L > 0.1 μm. Higher ZT is possible at higher temperatures for shorter c-GNRs, e.g. ZT = 3.25 is predicted at T = 800 K and  μm (Figures 3b and 4).

μm (Figures 3b and 4).

Thermoelectric figure of merit, ZT, for chevron-type GNR with randomly distributed heavy precursors.

ZT is plotted as a function of chemical potential (μ) and length (L) at T = 800 K, (a). The heavy precursor density is d = 50%. Local maxima appear close to the band edges and the maximum value is obtained inside the band gap for all lengths. ZT for optimum system lengths are plotted at T = 300 K (blue), 500 K (green)and 800 K (red), (b). Electron density of states is depicted in gray. The system lengths are L = 430 nm, 140 nm and 70 nm, respectively. ZT = 3.25 is realized at 800 K.

Maximum ZT as a function of length at different temperatures.

Maximum ZT achievable when Anderson type disorder is introduced in the electronic Hamiltonian. The variation of onsite energies are set equal to the temperature, σ = kBT. Solid lines represent hole-like transport while the dashed lines are for electron-like charge carriers. The ZTmax values shown are realized inside the band gap, i.e. |μ| < 0.75 eV with respect to the mid-gap, except for the dotted curve (T = 300 K) when |μ| > 1.

Discussion

The length dependence of maximum ZT at different temperatures, ZTmax, displays the trade off due to electron and phonon scatterings in TE transport (Figure 4). In contrast to the pristine electron prediction that ZTmax increases monotonically with length, electron scattering results in a substantial reduction with L. At T = 300 K, a high ZT is assured for a wide range of c-GNR lengths from 0.01 to 5 μm, while at T = 500 K and 800 K the ranges are narrower and the peak positions shift to shorter L. Stronger suppression of electronic transport at higher temperatures is the reason for the narrowing and the shift of the peak positions in the ZTmax curves. On the other hand, κph is almost insensitive to temperature for L ≥ 0.1 μm, which is due to extremely short phonon MFPs as a result of hybrid nanostructuring. P being robust to changes in temperature for both valence and conduction bands and κph being saturated at relatively low temperatures are key aspects in the enhanced ZT values. As a final comment, s-GNRs with the same type of distribution of isotopes and Anderson disorder have ZT values smaller than 0.5 in the given range of L.

In summary, the combination of geometrical structuring and isotope engineering at the precursor level makes it possible to optimize both electronic and phononic transport properties of the considered carbon nanomaterials which have already been realized with existing fabrication technology. Noting that ZT > 3 is the goal for efficient thermoelectrics50,51, isotopically engineered c-GNRs are good candidates for technological applications, especially at elevated temperatures. The proposed hybrid nanostructuring scheme is promising for efficient TE energy conversion and thermal management of nano-devices. This scheme is not limited to carbon based systems but it is applicable to low-dimensional structures in general.

Methods

In this work, electronic Hamiltonians and overlap matrices as well as the interatomic force constants are obtained using the density functional tight binding (DFTB) method as implemented in the DFTB+ sofware package52,53. The electronic transport problem is treated using the non-equilibrium Green's function (NEGF) formalism45, while atomistic Green's function (AGF) technique is implemented for phonons44. Both electronic and phononic Green's functions are calculated recursively54. Thermoelectric coefficients are obtained from microscopic transport calculations55. More details about implementations of the methods are explained in the Supplementary Information.

Change history

01 March 2013

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

Vining, C. B. An inconvenient truth about thermoelectrics. Nature Materials 8, 83–85 (2009).

Galli, G. & Donadio, D. Thermoelectric materials: Silicon stops heat in its tracks. Nat Nano 5, 701–702 (2010).

Hicks, L. D. & Dresselhaus, M. S. Thermoelectric figure of merit of a one-dimensional conductor. Phys. Rev. B 47, 16631–16634 (1993).

Balandin, A. & Wang, K. L. Effect of phonon confinement on the thermoelectric figure of merit of quantum wells. Journal of Applied Physics 84, 6149–6153 (1998).

Zou, J. & Balandin, A. Phonon heat conduction in a semiconductor nanowire. Journal of Applied Physics 89, 2932–2938 (2001).

Hochbaum, A. I. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of rough silicon nanowires. Nature 451, 163–167 (2009).

Boukai, A. I. et al. Silicon nanowires as efficient thermoelectric materials. Nature 451, 168–171 (2008).

Lee, E. K. et al. Large thermoelectric figure-of-merits from sige nanowires by simultaneously measuring electrical and thermal transport properties. Nano Letters 12, 2918–2923 (2012).

Markussen, T., Jauho, A.-P. & Brandbyge, M. Electron and phonon transport in silicon nanowires: Atomistic approach to thermoelectric properties. Phys. Rev. B 79, 035415 (2009).

Markussen, T., Jauho, A.-P. & Brandbyge, M. Surface-decorated silicon nanowires: A route to high-zt thermoelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 055502 (2009).

Sevinçli, H. & Cuniberti, G. Enhanced thermoelectric figure of merit in edge-disordered zigzag graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 81, 113401 (2010).

Li, W., Sevinçli, H., Cuniberti, G. & Roche, S. Phonon transport in large scale carbon-based disordered materials: Implementation of an efficient order-n and real-space kubo methodology. Phys. Rev. B 82, 041410 (2010).

Haskins, J. et al. Control of thermal and electronic transport in defect-engineered graphene nanoribbons. ACS Nano 5, 3779–3787 (2011).

Li, W., Sevinçli, H., Roche, S. & Cuniberti, G. Efficient linear scaling method for computing the thermal conductivity of disordered materials. Phys. Rev. B 83, 155416 (2011).

Venkatasubramanian, R., Siivola, E., Colpitts, T. & O'Quinn, B. Thin-film thermoelectric devices with high room-temperature figures of merit. Nature 413, 597–602 (2001).

Harman, T. C., Taylor, P. J., Walsh, M. P. & LaForge, B. E. Quantum dot superlattice thermoelectric materials and devices. Science 297, 2229–2232 (2002).

Mingo, N., Hauser, D., Kobayashi, N. P., Plissonnier, M. & Shakouri, A. Nanoparticlein-Alloy Approach to Efficient Thermoelectrics: Silicides in SiGe. Nano Letters 9, 711–715 (2009).

Kim, W. et al. Thermal conductivity reduction and thermoelectric figure of merit increase by embedding nanoparticles in crystalline semiconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 045901 (2006).

Stoltz, G., Mingo, N. & Mauri, F. Reducing the thermal conductivity of carbon nanotubes below the random isotope limit. Phys. Rev. B 80, 113408 (2009).

Mingo, N., Esfarjani, K., Broido, D. A. & Stewart, D. A. Cluster scattering effects on phonon conduction in graphene. Phys. Rev. B 81, 045408 (2010).

Chen, Y., Jayasekera, T., Calzolari, A., Kim, K. W. & Nardelli, M. B. Thermoelectric properties of graphene nanoribbons, junctions and superlattices. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 22, 372202 (2010).

Huang, W., Wang, J.-S. & Liang, G. Theoretical study on thermoelectric properties of kinked graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 84, 045410 (2011).

Zhou, J., Yang, R., Chen, G. & Dresselhaus, M. S. Optimal bandwidth for high efficiency thermoelectrics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 226601 (2011).

Slack, G. A. CRC Handbook of Thermoelectrics, Editors: Rowe, D. M. and Raton, B. (CRC Press, 1995).

Geim, A. K. Graphene: Status and prospects. Science 324, 1530–1534 (2009).

Balandin, A. A. et al. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 8, 902–907 (2008).

Ghosh, S. et al. Extremely high thermal conductivity of graphene: Prospects for thermal management applications in nanoelectronic circuits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 151911 (2008).

Cai, W. et al. Thermal transport in suspended and supported monolayer graphene grown by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 10, 1645–1651 (2010).

Jauregui, L. A. et al. Thermal transport in graphene nanostructures: Experiments and simulations. ECS Transactions 28, 73–83 (2010).

Seol, J. H. et al. Two-Dimensional Phonon Transport in Supported Graphene. Science 328, 213–216 (2010).

Evans, W. J., Hu, L. & Keblinski, P. Thermal conductivity of graphene ribbons from equilibrium molecular dynamics: Effect of ribbon width, edge roughness and hydrogen termination. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 203112–3 (2010).

Nika, D. L., Pokatilov, E. P., Askerov, A. S. & Balandin, A. A. Phonon thermal conduction in graphene: Role of umklapp and edge roughness scattering. Phys. Rev. B 79, 155413–12 (2009).

Munoz, E., Lu, J. & Yakobson, B. I. Ballistic thermal conductance of graphene ribbons. Nano Letters 10, 1652–1656 (2010).

Lindsay, L., Broido, D. A. & Mingo, N. Diameter dependence of carbon nanotube thermal conductivity and extension to the graphene limit. Phys. Rev. B 82, 161402 (2010).

Ghosh, S. et al. Dimensional crossover of thermal transport in few-layer graphene. Nat. Mater. 9, 555–558 (2010).

Balandin, A. A. Thermal properties of graphene and nanostructured carbon materials. Nature Materials 10, 569–581 (2011).

Nika, D. L. & Balandin, A. A. Two-dimensional phonon transport in graphene. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 24, 233203 (2012).

Sevik, C., Sevinçli, H., Cuniberti, G. & Çağin, T. Phonon engineering in carbon nanotubes by controlling defect concentration. Nano Letters 11, 4971–4977 (2011).

Chen, S. et al. Thermal conductivity of isotopically modified graphene. Nature Materials 11, 203–207 (2012).

Gunst, T., Markussen, T., Jauho, A.-P. & Brandbyge, M. Thermoelectric properties of finite graphene antidot lattices. Phys. Rev. B 84, 155449 (2011).

Cai, J. et al. Atomically precise bottom-up fabrication of graphene nanoribbons. Nature 466, 470–473 (2010).

Mahan, G. D. & Sofo, J. O. The best thermoelectric. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93, 7436–7439 (1996).

Aradi, B., Hourahine, B. & Frauenheim, T. DFTB+, a sparse matrix-based implementation of the dftb method. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 111, 5678–5684 (2007).

Mingo, N. & Yang, L. Phonon transport in nanowires coated with an amorphous material: An atomistic green's function approach. Phys. Rev. B 68, 245406 (2003).

Haug, H. & Jauho, A.-P. Quantum Kinetics in Transport and Optics of Semiconductors (Springer, 1996).

Ziman, J. M. Electrons and Phonons (Oxford University Press, New York, 2001).

Jiang, J.-W., Lan, J., Wang, J.-S. & Li, B. Isotopic effects on the thermal conductivity of graphene nanoribbons: Localization mechanism. Journal of Applied Physics 107, 054314 (2010).

Anderson, P. W. Absence of diffusion in certain random lattices. Phys. Rev. 109, 1492–1505 (1958).

White, C. T. & Todorov, T. N. Carbon nanotubes as long ballistic conductors. Nature 393, 240 (1998).

Dresselhaus, M. et al. New directions for low-dimensional thermoelectric materials. Advanced Materials 19, 1043–1053 (2007).

Tritt, T. M., Bttner, H. & Chen, L. Thermoelectrics: Direct solar thermal energy conversion. MRS Bulletin 33, 366–368 (2008).

Frauenheim, T. et al. A self-consistent charge density-functional based tight-binding method for predictive materials simulations in physics, chemistry and biology. physica status solidi (b) 217, 41–62 (2000).

Togo, A., Oba, F. & Tanaka, I. First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and cacl2-type sio2 at high pressures. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134106 (2008).

Sancho, M. P. L., Sancho, J. M. L. & Rubio, J. Highly convergent schemes for the calculation of bulk and surface green functions. Journal of Physics F: Metal Physics 15, 851 (1985).

Esfarjani, K., Zebarjadi, M. & Kawazoe, Y. Thermoelectric properties of a nanocontact made of two-capped single-wall carbon nanotubes calculated within the tight-binding approximation. Phys. Rev. B 73, 085406 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support by the priority program Nanostructured Thermoelectrics (SPP-1386) of the German Research Foundation (DFG) (Contract No. CU44/11-1), the German Excellence Initiative via the Cluster of Excellence EXC 1056 “Center for Advancing Electronics Dresden” (cfAED), the European Union (ERDF) and the Free State of Saxony via TP A2 (“MolFunc”/“MolDiagnosik”) of the Cluster of Excellence “European Center for Emerging Materials and Processes Dresden” (ECEMP). H.S. acknowledges funding from the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF). C.S. and T.C. acknowledge support from NSF (DMR 0844082) to International Institute of Materials for Energy Conversion at Texas A&M University. The parts of computations are carried out at the facilities of Laboratory of Computational Engineering of Nanomaterials also supported by ARO, ONR and DOE grants. We also would like to thank for generous time allocation made for this project by the Supercomputing Center of Texas A&M University. C.S. acknowledges the support from The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) to his research at Anadolu University. G.C. further acknowledges the World Class University program funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology through the National Research Foundation of Korea (R31-10100). The Center for Information Services and High Performance Computing (ZIH) at the TU-Dresden is also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. conceived the research. C.S. did the DFTB simulations. H.S. did the NEGF and AGF calculations. T.C. and G.C. oversaw all research phases. Everyone contributed to the writing of the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information. A bottom-up route to enhance thermoelectric figures of merit in graphene nanoribbons

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sevinçli, H., Sevik, C., Çağın, T. et al. A bottom-up route to enhance thermoelectric figures of merit in graphene nanoribbons. Sci Rep 3, 1228 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01228

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01228

This article is cited by

-

Enhancement of the thermoelectric properties in bilayer graphene structures induced by Fano resonances

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Infrared spectroscopy of graphene nanoribbons and aromatic compounds with sp3C–H (methyl or methylene groups)

Journal of Materials Science (2021)

-

Chemically doped macroscopic graphene fibers with significantly enhanced thermoelectric properties

Nano Research (2018)

-

Multifunctionality of Carbon-based Frameworks in Lithium Sulfur Batteries

Electrochemical Energy Reviews (2018)

-

Nanostructural thermoelectric materials and their performance

Frontiers in Energy (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.