Abstract

Day-scale Earth's free oscillation after large earthquakes has been detected by underground instruments such as strainmeters, gravimeters and seismometers, to investigate Earth's internal structure, geodynamics and source properties of earthquakes. Here we show that Global Positioning System (GPS) can also detect the signals of the Earth's free oscillation. A dense GPS array in Japan (GEONET) recorded the surface deformation following the 2011 Tohoku megathrust earthquake. A simple array analysis over 300 stations reduces local noise in GPS time series. We find that the dense GPS array truly detected both spheroidal and toroidal fundamental modes in three-direction displacement. This new tool has a strong potential to investigate the free oscillations particularly in low-frequency bands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vibration of an elastic sphere has been theoretically calculated from the 19th century and Earth's free oscillation was first observed after the 1960 Chilean earthquake1,2. Many following studies revealed the Earth's internal structure, geodynamics and source properties of earthquakes by using the free oscillation signals3,4,5,6. Recently it was found that the Earth's free oscillation continuously occurs in limited modes7,8,9.

Strainmeters, gravimeters and broadband seismometers served a role in observing the free oscillation signals. These instruments have good signal-to-noise ratios in corresponding frequency bands. However, Global Positioning System (GPS) has not been used for the purpose despite its advantages of three-component observation in displacement and flat frequency response to 0 Hz. If we reduce much noise contained in GPS time series, GPS would be a powerful tool to detect small displacement signals by the free oscillation as well as seismic waves10,11.

Here we focus on the Earth's free oscillation after the 2011 Tohoku megathrust earthquake12,13,14. A dense GPS array in Japan, called GEONET, continuously observed postseismic land deformation15,16 after the occurrence of the mainshock (JST 14:46 on March 11). Using time-series data at GEONET stations, we look for the signals of the Earth's free oscillation in a low-frequency range (> 250 seconds). Since the low-frequency range corresponds to a long-wavelength range over several hundred kilometers, we can stack spectral data at many stations to improve signal-to-noise ratios. Figure 1 shows 341 GEONET stations near the source region of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake that we focus on. The period to obtain Fourier amplitude spectra is 18 hours (from JST 15:00 on March 11 to 9:00 on March 12).

341 GPS stations in NE Japan.

We use displacement time-series at 341 GEONET stations near the source region of the 2011 Tohoku megathrust earthquake, as represented by solid triangles. The beach-ball symbol shows the GCMT solution17. The moment magnitude is 9.1. The dashed squares illustrate the ruptured area estimated by GEONET data18.

Results

Figure 2 presents the absolute values of the stacked amplitude spectra in three directions (North-South, East-West and vertical components) over the 341 stations. The systematic increases of the amplitude toward 0 Hz reflect the postseismic deformation owing to afterslip at the plate interface15,16 and tides. We confirm many spectral peaks, corresponding to fundamental spheroidal (0Sn, n = 0, 2, 3, 4, et al.) and toroidal (0Tn, n = 2, 3, 4, et al.) modes.

Observed amplitude spectrum with frequencies of fundamental modes.

The stacked Fourier amplitude spectra over the 341 stations. The red thick solid line is the N-S component, the green dashed line is the E-W component and the blue thin solid line is the vertical component. (Upper figure) The vertical black lines represent frequencies of the fundamental spheroidal modes based on the Preliminary Reference Earth Model19. A reference of steady oscillation with 1 mm amplitude in time domain is added at the bottom right. (Lower figure) Compared with the fundamental toroidal modes.

The spheroidal modes should appear in both vertical and horizontal components20. In Figure 2, we can identify all of the fundamental spheroidal modes excluding 0S2 from the vertical component. The mean signal amplitudes during the 18 hours correspond to steady oscillations with submillimeter amplitudes. By contrast, the toroidal modes principally appear in horizontal components20. The signals of the toroidal modes mainly contribute to the N-S movement inferred from the location of the GPS stations and the earthquake mechanism (Figure 1). Focusing on the spectral peaks of the N-S component in Figure 2, we can recognize good consistency with 0T2 and possible other toroidal modes, e.g., 0T10, 0T11. The characteristic frequencies of the toroidal modes actually do not correspond to the observed spectral peaks of the vertical component. To focus on a specific mode, longer datasets than 18 hours or coordinate rotation in the time-series data would be useful.

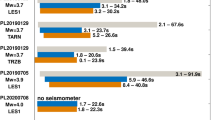

In order to compare the GPS results with other instruments, we also analyse time-series data of broadband seismometer (STS-121) during the same period. Figure 3 shows the comparative results of the GPS array and the seismometer. For the GPS spectra (left figure), the original time-series data in displacement are transformed into velocity. The STS-1 seismometer that we use is located at Yamizo station of the F-net broadband seismograph network. The instrument response of the STS-1 seismometer is corrected.

Comparison between GPS and STS-1 seismometer.

Station locations of the GPS array and the STS-1 seismometer and their amplitude spectra. (Left) The same results of the GPS spectra in Figure 2 but the original time-series data in displacement are transformed into velocity. (Right) Amplitude spectra of the STS-1 seismometer at Yamizo station (140.24N, 36.93E, as marked in the upper right figure by the solid star). The instrument response of the seismometer is corrected.

The comparison between the GPS array and the broadband seismometer implies: (1) The GPS array detected the signals of the Earth's free oscillation comparable to the seismometer. (2) The background noise levels of the GPS array are higher than the seismometer, but the GPS array seems better in a very low frequency range (roughly < 0.3 mHz).

Discussion

We revealed that the dense GPS array truly caught the signals of the Earth's free oscillation after the megathrust earthquake, using the simple stacking method. Although the background noise of the GPS array were still higher than the broadband seismometer, the flat response to 0 Hz of GPS led to the relatively lower noise in the very low frequency range. In addition, compared with gravimeters, GPS has an advantage of three-direction observation (two horizontal directions in addition to vertical direction). These facts indicate that GPS has a strong potential to investigate subseismic low-frequency bands22. Using more datasets in the world with proper time-series processing would be required to investigate a specific mode.

The GPS time-series data were analysed by a kinematic Precise Point Positioning method23,24, not by a baseline analysis method. This allowed us to detect the signals of the Earth's free oscillation with long wavelengths over several hundred kilometres. The phases of the low-frequency waves at the GPS stations do not vary significantly. Thus the simple stacking method illuminated the free oscillation signals. To check the efficiency of the stacking, we show comparative examples of the all-stacked result (341 stations), a partly-stacked result (30 stations) and a non-stacked result (1 station) in Figure 4. The signals of the Earth's free oscillation may appear even in the non-stacked case, however, the flutters of the spectra tend to hide the free oscillation signals in the non-stacked and partly-stacked cases.

Effects of stacking.

Comparative examples of the all-stacked result (341 stations), a partly-stacked result (30 stations) and a non-stacked result (1 station) for the GPS amplitude spectra in vertical displacement. We randomly select the 30 stations for the partly-stacked result and use the data at Awashimaura station (139.25N, 38.47E) for the non-stacked result.

Methods

First, we obtain the GPS time-series data by the kinematic PPP method using RTnet software, from RINEX files provided by Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. The sampling rate Δt is 30 seconds. In the analysis, carrier phase data, ephemeris data and clock data are used. The ephemeris is the IGS final orbit (with an interval of 15 minutes) and the clock is also the IGS final orbit (with an interval of 30 seconds). Based on the precise ephemeris and clock, absolute coordinate at each station is sequentially estimated in parallel with tropospheric delay. Ionospheric delay is excluded by combination of dual-frequency carrier phase observations.

To look for the signals of the Earth's free oscillation, we use the displacement time-series data during 18 hour after the mainshock in three directions: North-South component, East-West component and vertical component. No particular time-series processing such as detrending has been done. We compute discrete Fourier transform of the time-series data by an FFT method with the Hann window25 at all the stations for each component:

where D is the data in the frequency domain, Δt is the sampling rate (30 seconds), N is total number of the time series with zero padding and d is the original time-series data. The Fourier amplitude spectrum is given by the absolute value of D. Then we simply stack the amplitude spectra over the stations for each component (N-S, E-W and vertical).

We also process the STS-1 seismometer data by a similar method. The original time-series data is provided by National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention (NIED). There are two different points from the GPS case in processing the data. The first is the correction of the instrument response. The Fourier amplitude spectrum for the seismometer data is given by the absolute value of D divided by a complex transfer function (whose poles and zeroes are supplied by NIED). The second is that the sampling rate Δt of the seismometer data is 0.01 seconds.

References

Benioff, H., Press, F. & Smith, S. Excitation of the free oscillations of the Earth by earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. 66, 605–619 (1961).

Ness, N. F., Harrison, J. C. & Slichter, L. B. Observations of the free oscillations of the Earth. J. Geophys. Res. 66, 621–629 (1961).

Gilbert, F. & Dziewonski, A. M. An application of normal mode theory to the retrieval of structural parameters and source mechanisms from seismic spectra. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London A. 278, 187–269 (1975).

Beroza, G. C. & Jordan, T. H. Searching for slow and silent earthquakes using free oscillations. J. Geophys. Res. 95, 2485–2510 (1990).

Park, J., Song, A., Tromp, J., Okal, E., Stein, S., Roult, G., Clevede, E., Laske, G., Kanamori, H., Davis, P., Berger, J., Braitenberg, C., Van Camp, M., Lei, X., Sun, H., Xu, H. & Rosat, S. Earth's free oscillations excited by the 26 December 2004 Sumatra-Andaman Earthquake. Science 308, 1139–1144 (2005).

Tanimoto, T. & Ji, C. Afterslip of the 2010 Chilean earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L22312 (2010).

Nawa, K., Suda, N., Fukao, Y., Sato, T., Aoyama, Y. & Shibuya, K. Incessant excitation of the Earth's free oscillations. Earth Planets Space 50, 3–8 (1998).

Kobayashi, N. & Nishida, K. Continuous excitation of planetary free oscillations by atmospheric disturbances. Nature 395, 357–360 (1998).

Suda, N., Nawa, K. & Fukao, Y. Earth's background free oscillations. Science 279, 2089–2091 (1998).

Larson, K. M., Boden, P. & Gomberg, J. Using 1-Hz GPS data to measure deformations caused by the Denali fault earthquake. Science 300, 1421–1424 (2003).

Houlie, N., Occhipinti, G., Blanchard, T., Shapiro, N., Lognonne, P. & Murakami, M. New approach to detect seismic surface waves in 1Hz-sampled GPS time series. Sci. Rep. 1, 10.1038/srep00044 (2011).

Igel, H., Nader, M.-F., Kurrle, D., Ferreira, M. G., Wassermann, J. & Ulrich Schreiber, K. Observations of Earth's toroidal free oscillations with a rotation sensor: The 2011 magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L21303 (2011).

Zábranová, E., Matyska, C., Hanyk, L. & Pálinkáš, V. Constraints on the Centroid Moment Tensors of the 2010 Maule and 2011 Tohoku Earthquakes from radial modes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L18302 (2012).

Okal, E. From 3-Hz P waves to 0S2: No evidence of a slow component to the source of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake. Pure Appl. Geophys. (in press).

Ozawa, S., Nishimura, T., Suito, H., Kobayashi, T., Tobita, M. & Imakiire, T. Coseismic and postseismic slip of the 2011 magnitude-9 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Nature 475, 373–377 (2011).

Ozawa, S., Nishimura, T., Munekane, H., Suito, H., Kobayashi, T., Tobita, M. & Imakiire, T. Preceding, coseismic & postseismic slips of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, Japan. J. Geophys. Res. 117, B07404 (2012).

Nettles, M., Ekström, G. & Koss, H. C. Centroid-moment-tensor analysis of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake and its larger foreshocks and aftershocks. Earth Planets Space 63, 519–523 (2011).

Nishimura, T., Munekane, H. & Yarai, H. The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku Earthquake and its aftershocks observed by GEONET. Earth Planets Space 63, 631–636 (2011).

Dziewonski, A. M. & Anderson, D. L. Preliminary reference Earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. Int. 25, 297–356 (1981).

Saito, M. Excitation of free oscillations and surface waves by a point source in a vertically heterogeneous Earth. J. Geophys. Res. 72, 3689–3699 (1967).

Wielandt, E. & Streckeisen, G. The leafspring seismometer: design and performance. Bull. Seis. Soc. Am. 72, 2349–2367 (1982).

Freybourger, M., Hinderer, J. & Trampert, J. Comparative study of superconducting gravimeters and broadband seismometers STS-1/Z in seismic and subseismic frequency bands. Phys. Earth Planet. Int. 101, 203–217 (1997).

Zumberge, J. F., Heftin, M. B., Jefferson, D. C., Watkins, M. M. & Webb, F. H. Precise point positioning for the efficient and robust analysis of GPS data from large networks. J. Geophys. Res. 102, 5005–5017 (1997).

Kouba, J. & Heroux, P. GPS precise point positioning using IGS orbit products. GPS Solution 5, 12–28 (2000).

Blackman, R. B. & Tukey, J. W. Particular pairs of windows. in the Measurement of Power Spectra from the Point of View of Communications Engineering, New York Dover 95–101 (1959).

Wessel, P. & Smith, W. H. F. New version of the generic mapping tools released. Eos, Trans. AGU 76, 329 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We thank Tetsuya Iwabuchi about the analysis of the GPS time-series data. We also appreciate Geospatial Information Authority of Japan, NGDS, the VERIPOS/APEX service, Hitz, GPS Solutions inc. and National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention providing the datasets. Generic Mapping Tools26 is used to draw maps.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.M. computed the spectra and wrote the paper; K.H. proposed the initial idea and discussed the results.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareALike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Mitsui, Y., Heki, K. Observation of Earth's free oscillation by dense GPS array: After the 2011 Tohoku megathrust earthquake. Sci Rep 2, 931 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00931

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00931

This article is cited by

-

Earth’s free oscillations excited by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake recorded in multiple GPS networks

Earth, Planets and Space (2021)

-

GPS source solution of the 2004 Parkfield earthquake

Scientific Reports (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.