« Prev Next »

No one could have predicted that experiments designed to understand bacterial pneumonia would lead to the discovery of DNA as the hereditary material. In the early part of the twentieth century, before the advent of antibiotics, pneumococcal infections claimed many more lives than they do today. Researchers on both sides of the Atlantic were thus actively engaged in studying Streptococcus pneumoniae, the bacterium responsible for clinical infections. Early on, it became apparent that multiple strains of S. pneumoniae were responsible for causing bacterial pnuemonia. Researchers also noted that patients developed antibodies to the particular strain, or serotype, with which they were infected, but these antisera were not universally reactive against pneumococcal strains. However, the bacterial isolates and serum samples from these clinical studies provided the critical reagents for the experiments that ultimately led to the identification of DNA as the hereditary material.

Pneumococcal Research Provides Critical Tools in DNA Research

Although numerous scientists engaged in pneumococcal research during the first half of the twentieth century, two of these researchers played an especially important role in the course of events that led to the discovery of DNA as the hereditary material. One of these individuals was Oswald Avery. Avery joined the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, now the Rockefeller University, in 1913 as part of a team seeking to develop a therapeutic serum for treating lobular pneumonia. Avery believed that knowledge of the chemical composition of the pneumococcus bacterium was essential for understanding and treating the disease. He perfected his biochemical technique by focusing on the chemical composition of the capsule that surrounded virulent S strains of pneumococci. In his early work, Avery helped establish that polysaccharides were a major component of the pneumococcal capsule and that capsules from different serotypes of pneumococci had distinctive polysaccharide compositions. Avery also concerned himself with the role of capsules in pathogenicity, as capsules were notably absent from the surface of nonvirulent R forms of streptococci. Defying the conventional wisdom of the time, Avery hypothesized that the polysaccharides in the capsules were the actual antigens stimulating the production of antibodies in infected patients (Avery & Goebel, 1933).

Purification of the Active Transforming Principle

When Avery first became aware of Griffith's results, he treated them with skepticism. Other researchers and laboratories, however, were quick to reproduce and build upon Griffith's data. Within a few years, Sia and Dawson (1931) showed that transformation could be carried out in liquid cultures of pneumococci as well as in mice, allowing more precise control of environmental variables in transformation experiments. In 1932, Alloway further demonstrated that the active transforming principle was present in sterile, cell-free extracts prepared from heat-treated pneumococci by filtration. These additional findings convinced Avery that the transforming principle could be identified, and he applied his considerable biochemical expertise to its purification from pneumococcal extracts (Avery et al., 1944).

A critical aspect of any biochemical purification is the development of an assay, or a way to measure the activity of interest. For their experiments, Avery and his colleagues developed conditions under which R cells could be reliably transformed into S cells using extracts of heat-killed Type III S cells. These same conditions could then be used to measure transforming activity in fractions obtained at different steps in the purification process. To quantify the actual amount of transforming principle in a fraction, each sample was tested at a series of increasing dilutions. These data represent four identical experiments in which Avery and his colleagues tested the ability of the purified factor, designated preparation 44, to transform Type II R cells into Type III S cells. The transforming activity was very concentrated in the extract, since it could be diluted ten-thousand-fold without losing its transforming ability. Fractions that maintained transforming activity at the highest dilutions were deemed to possess the highest concentration of transforming activity. Specifically, when at least 0.01μg of the extract was added to cells, transformation was observed. When any less than 0.01μg was added, the transformation was inconsistent (comparing samples 1 and 3 with 2 and 4) (Figure 2).

Physical Characterization of the Transforming Principle

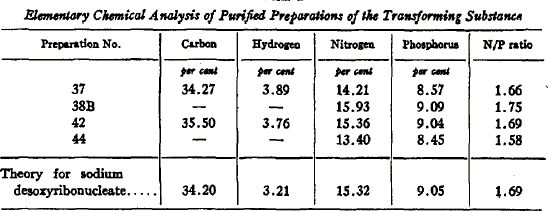

Avery and his colleagues submitted the purified transforming principle to rigorous physical characterization in order to demonstrate that it possessed the properties expected of DNA (Avery et al., 1944). The elemental composition of the purified transforming compound was close to the theoretical values for DNA (last row, sodium desoxyribonucleate) (Figure 3). Significantly, the purified principle had a high phosphorous content, which is characteristic of DNA, but not of proteins.

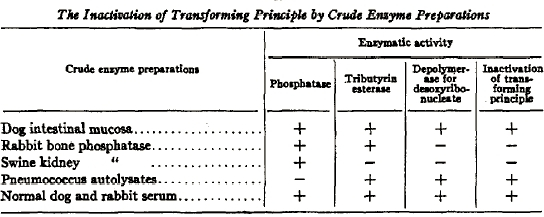

Consistent with these results, the factor gave positive reactions in chemical tests for DNA, but negative or weakly positive reactions in tests for proteins and RNA. Other tests indicated that the transforming principle was a very large molecule that absorbed the same spectrum of ultraviolet light as DNA. However, the most definitive proof that the transforming principle was DNA was its sensitivity to specific enzymes, called DNAses, that specifically degrade different kinds of DNA. Avery and his colleagues were able to show that transforming activity was not destroyed by enzymes that degrade proteins or RNA. At the time, Avery could not obtain samples of pure DNAse. Instead, Avery and his colleagues used crude preparations from animal tissues that were known to contain DNAse activity. They then measured the ability of these various crude preparations to destroy the transforming principle in parallel with measurements of phosphatase, esterase, and DNAse activities in the same extracts. In all cases, the ability of the crude extracts to destroy the transforming principle was proportional to their DNAse activity, measured with pure calf thymus DNA as substrate (Figure 4).

DNA Has the Properties Expected of Genes

In retrospect, the experiments reported in Avery and his colleagues' landmark paper of 1944 provided convincing proof that DNA was the hereditary material. It is not surprising, however, that it took some time for the community to adopt the new "dogma" of DNA as the genetic material. Before the experiments of Avery and Griffith, the dogma of the time was that protein was the genetic material, as it was present in the nucleus in nearly equal amounts as DNA, and was structurally more diverse. It was easier to imagine a genetic "language" of 20 symbols than of merely four repeating symbols. The details of the information transfer from DNA to protein were still undiscovered, and many scientists were reluctant to dismiss proteins, which are more structurally diverse than DNA, as the genetic material. Avery and his colleagues (1944) clearly appreciated the importance of their findings, however. They noted that transformation produced changes that are "predictable, type-specific, and heritable" and that "[n]ucleic acids of this type must be regarded not merely as structurally important but as functionally active in determining the biochemical activities and specific characteristics of pneumococcal cells."

References and Recommended Reading

Alloway, J. L. The transformation in vitro of R pneumococci into S forms of different specific types by the use of filtered pneumococcus extracts. Journal of Experimental Medicine 55, 91–99 (1932)

Avery, O. T., & Goebel, W. F. Chemoimmunological studies on the soluble specific substance of pneumococcus I: The isolation and properties of the acetyl polysaccharide of pneumococcus type I. Journal of Experimental Medicine 58, 731–755 (1933)

Avery, O. T., MacLeod, C. M., & McCarty, M. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types: Induction of transformation desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from pneumococcus type III. Journal of Experimental Medicine 79, 137–157 (1944)

Griffith, F. The significance of pneumococcal types. Journal of Hygiene 27, 113–159 (1928)

McCarty, M. Discovering genes are made of DNA. Nature 421, 406 (2003) doi:10.1038/nature01398 (link to article)

National Library of Medicine. "Profiles in Science: Oswald T. Avery Collection." (accessed on September 30, 2008)

Sia, R. H. P., & Dawson, M. H. In vitro transformation of pneumococcal types II: The nature of the factor responsible for the transformation of pneumococcal types. Journal of Experimental Medicine 54, 701–710 (1931)

Steinman, R. M., & Moberg, C. L. A triple tribute to the experiment that transformed biology. Journal of Experimental Medicine 179, 379–384 (1994)

Figure 1: Griffith's experiments on pneumococci.

Figure 1: Griffith's experiments on pneumococci.